Nurses are playing a major role in the political process for planning the future of health care.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define politics and political involvement.

• State the rationale for a nurse to become involved in the political process.

• List specific strategies needed to begin to affect the laws that govern the practice of nursing and the health care system.

• Discuss different types of power and how each is obtained.

• Describe the function of a political action committee.

• Discuss selected issues affecting nursing: multistate licensure, nursing and collective bargaining, and equal pay for work of comparable value.

Too often nurses feel that the legislative process is associated with wheeling and dealing, smoke-filled rooms, and the exchange of money, favors, and influence. Many believe politics to be a world that excludes people with ethics and sincerity—especially given the controversies in presidential administrations and political party ideologies that so often result in gridlock. Others think only the wealthy, ruthless, or very brave play the game of politics. It seems that most nurses feel that the messy business of politicking should be left to others while they (nurses) do what they do best and enjoy most: taking care of patients.

Today, however, nurses are coming to realize that politics is not a one-dimensional arena but a complex struggle with strict rules and serious outcomes. In a typical modern-day political struggle, a rural health care center may be pitted for funding against a major interstate highway. Certainly, both projects have merit, but in times of limited resources not everyone can be victorious. Nurses are now aware that to influence the development of public policy in ways that affect how we are able to deliver care, we must be engaged in the political process.

Leavitt and colleagues (2002) wrote that “the future of nursing and health care may well depend on nurses’ skills in moving a vision. Without a vision, politics becomes an end in itself—a game that is often corrupt and empty” (p. 86). To demonstrate these skills, nurses must elect the decision makers, testify before legislative committee hearings, compromise, and get themselves elected to decision-making positions. Nurses realize that involvement in the political process is a vital tool that they must learn to use if they are to carry out their mission (providing quality patient care) with maximum impact.

Nurses’ recognition of problems in the current health care system, and their commitment to the principle that health care is a right of all citizens, fuel their desire to become active in the political arena and to form a collective force to improve the health care system.

An example of the power of the nursing collective is evidenced in organized nursing’s efforts to provide support and defense for a Texas nurse who was discharged from her hospital position for reporting a physician to the Texas Medical Board for medical patient care that the nurse believed was unsafe (ANA, 2010). The nurse, a member of the Texas Nurses Association and the American Nurses Association, also faced a third-degree felony charge for “misuse of official information.”

The Texas Nurses Association became aware of the case and immediately offered to support the nurse involved in the case and enlisted the support from the ANA as well. The call went out from the ANA to all nurses, and more than $45,000 was donated both by individuals and organizations from across the United States to support the defense of this nurse. ANA and the Texas Nurses Association strongly criticized the criminal charges and the fact that this case could have a long-term negative impact on nurses who are acting as whistle-blowers advocating for their patients.

The case went to trial, and a jury found the nurse not guilty. The ANA President at the time, Rebecca M. Patton, RN, MSN, CNOR, said of the outcome, “ANA is relieved and satisfied that Anne Mitchell (RN) was vindicated and found not guilty on these outrageous criminal charges—today’s verdict is a resounding win on behalf of patient safety in the U.S. Nurses play a critical, duty-bound role in acting as patient safety watch guards in our nation’s health care system. The message the jury sent is clear: the freedom for nurses to report a physician’s unsafe medical practices is nonnegotiable. However, ANA remains shocked and deeply disappointed that this sort of blatant retaliation was allowed to take place and reach the trial stage—a different outcome could have endangered patient safety across the U.S., having a potential chilling effect that would make nurses think twice before reporting shoddy medical practice. Nurse whistle-blowers should never be fired and criminally charged for reporting questionable medical care” (ANA, 2010, para 5).

It is important for nurses to join and to support nursing organizations that advocate and lobby on behalf of nurses, nursing, and quality health care. Not all nursing organizations have a governmental affairs division for lobbying. The American Nurses Association has lobbyists in Washington, DC, to advocate for the concerns of the profession. In addition, most of the constituent state nurses associations have legislative activities at the state level. (Several nursing associations, including the ANA, are described in Chapter 9.) Before joining a nursing association, you should ask whether the association lobbies on behalf of the interests of its members. The future power of nurses depends on nurses joining and supporting such associations.

The nursing profession will also continue to work with the national media to portray nurses in a positive, professional light. For nurses to be effective in promoting policy, the public needs a clear picture of what nurses bring to the American health care delivery system. For example, ANA responded to an event dealing with a nurse who was competing in the Miss America contest and who was delivering a dramatic monologue about her experience as a nurse. A co-host of the television program “The View” mocked the monologue and the nurse for wearing a “doctor’s stethoscope,” as if the nurse were wearing a costume.

ANA led a national outcry over this situation with the message “nurses don’t wear costumes; they save lives.” As a result, there was so much public and advertiser backlash over this comment that the network, the television program, and the co-host issued an apology (ANA, 2015a).

What Exactly is Politics?

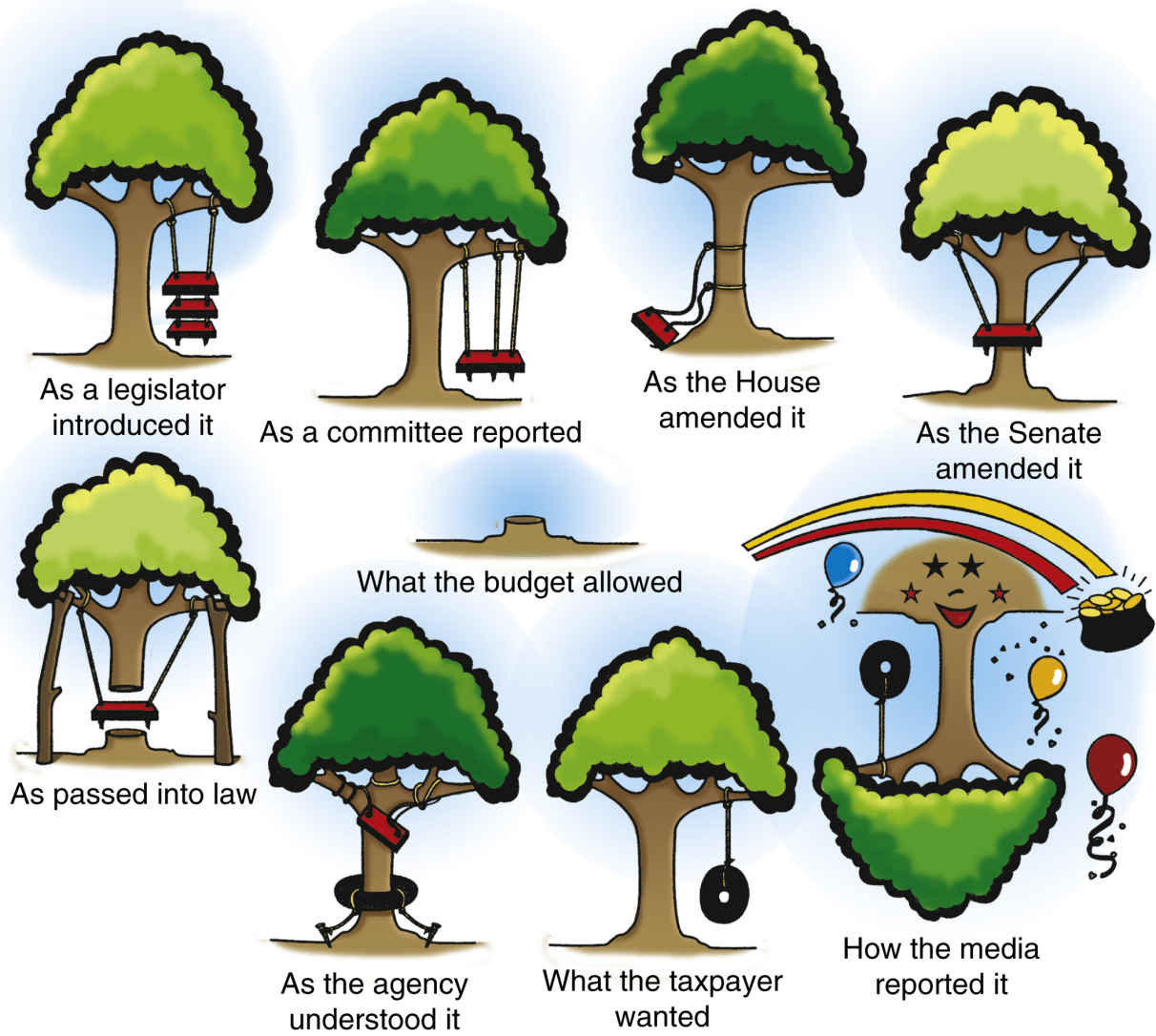

Politics, described by (Mason et al., 2007, p. 4), is a vital tool that enables the nurse to “nurse smarter.” Involvement in the political process offers an individual nurse a tool that augments his or her power, or clout, to improve the care provided to patients. Whether on the community, hospital, or nursing-unit level, political skills and the understanding of how laws are enacted enable the nurse to identify needed resources, gain access to those resources, work with legislative bodies to lobby for changes in the health care system, and overcome obstacles, thus facilitating the movement of the patient to higher levels of health or function (Fig. 17.1).

Let us look first at the nursing-unit level:

Your hospital is in the process of selecting a new supplier of IV pumps. You and the other nurses on your unit want to have input into that decision, because IV pumps are essential to the care of your patients, and you have a definite opinion about the type of IV pump that works best. But the intensive care unit nurses, who are thought to be more important and valuable because the nursing shortage has made them as rare as hen’s teeth, have the only nurse position on the review committee (and therefore, the director’s ear!). You and the nurses on your unit strategize to secure input into this important decision.

Your plan might look like this:

▪ Gather data about IV pumps—cost, suppliers, possible substitutes, and so on.

▪ Communicate to the charge nurse and supervisor your concern about this issue and your plans to become involved in the decision (by using appropriate channels of communication).

▪ State clearly what you want—perhaps request a seat on the committee when the opportunity arises.

▪ Summarize in writing your request and the rationale, submitting it to the appropriate people.

▪ Establish a coalition with the intensive care unit nurses and other concerned individuals.

▪ Become involved with other hospital issues, and contribute in a credible fashion (i.e., do not be a single-issue person).

What Other Strategies Would You Suggest?

The scenario described here illustrates what a politically astute nurse would do in this situation. Although the example applies to a hospital setting, the strategies are comparable to those necessary for becoming involved on a community, state, or even federal level. Practicing at the local level will provide good experience for larger issues—one has to start somewhere. Furthermore, a nurse involved on the local level will be able to hone her or his skills, thus gaining confidence in the ability to handle similar “exercises” in larger forums.

In the previous example, the nurse was able to formulate several “political” actions to influence the outcome of the IV pump decision (Critical Thinking Box 17.1).

What Are the Skills That Make Up a Nurse’s Political Savvy?

Ability to Analyze an Issue (Those Assessment Skills Again!)

The individual who expects to “influence the allocation of scarce resources” must do the homework necessary to be well informed. She or he must know all the facts relevant to the issue, how the issue looks from all angles, and how it fits into the larger picture.

Ability to Present a Possible Resolution in Clear and Concise Terms

Ability to Participate in a Constructive Way

Too often, a person disagrees with a proposal being suggested to a hospital unit (or city council) but only gripes about it. The displeased individual seldom takes the time to study the problem or to understand its connection with other hospital departments (or city programs in a broader issue). Most important, the displeased person seldom suggests an alternate solution.

In short, if an individual’s concern is not directed toward solving the problem, that person will not be seen as a team player but as a troublemaker. Constructive responses, perhaps something as simple as posing a single question such as “What solution would you suggest?” may help those involved think in positive terms and redirect energy to a more productive mode. Positive action can produce the kind of creative brainstorming that results in a solution.

Ability to Voice One’s Opinion (Understand the System)

After the homework is done, let the right person know the opinion or solution that has been determined. For example, the nurse might communicate concern and knowledge about the issue to the nurse manager and supervisor. It is important, of course, to make an intelligent and well-informed decision about the person to whom it is best to voice one’s opinion.

Having a confidant or mentor who knows the environment is one way to acquire this information, as he or she can provide you with insight regarding the appropriate person to whom you can express your opinion and suggestions. Another strategy is to use your listening skills. Simply standing back and listening are assets that will come in handy! Whatever the technique, studying the dynamics of the organization with all senses will help the nurse decide on the best person and the most appropriate way to communicate the proposed solution.

Ability to Analyze and Use Power Bases

While discussing issues with colleagues and studying the organization, be alert to the various power brokers. In the previous IV pump vignette, the nurse notes the VP of Purchasing is an obvious source of power in the hospital. This VP will certainly concur with, if not make, the final decision. However, be aware that power does not always follow the lines on the organizational chart. The power of the nurse aide on the oncology unit who just happens to be the niece of the newly appointed member of the Board of Trustees may escape the notice of some. This person could be used to influence a decision if necessary. Similarly, the fact that the VP of Purchasing’s mother was on the unit should be filed in your memory for future use.

Understanding policy that has been promulgated by respected bodies can also be used as a power base. For example, the Institute of Medicine issued a report in 2011 called The Future of Nursing. One of the major tenets of this respected report is that nurses should be able to practice to the full extent of their education, licensure, and training (IOM, 2011).

If a school nurse is trying to make a point about staffing in schools or about the expanded role of the school nurse, using such information can reinforce the power behind the message (Fleming, 2012). On a more global level, using such a power base can help to make the point that the expansion of the role of advanced practice nurses can help to alleviate the massive shortage of primary care physicians and can improve care processes (Newhouse et al., 2012).

Facts may be facts, but where one gets information can sometimes make a statement as powerful as the information itself. Having the ability to use many different channels of information will afford the nurse the power to choose among them.

What is Power, and Where does it Come from?

Sanford (1979) describes five laws of power. She recommends that these laws be studied to identify strategies to develop power in nursing. The laws are as follows:

Law 1: Power Invariably Fills Any Vacuum

When a problem or issue arises, the prevailing desire is for peace and order. People are willing to yield power to someone interested in restoring order to situations of discomfort. Therefore someone will eventually step forward to handle the dilemma. It may be some time before the discomfort or unrest grows to heights sufficient for someone to take the lead.

Nonetheless, a person exerting power will step forward to offer a solution. In some situations, this person may be the previously identified leader, the nurse manager, or the department chair. More often there is an official power broker influencing the action. Know that there are opportunities to exert influence—for example, by taking the leadership role (i.e., stepping forward to fill the vacuum).

Law 2: Power Is Invariably Personal

In most instances, programs are attributed to an organization. For example, the state and national children’s and health associations proposed a fictitious program called ImmunEYEs. If one investigated, however, it might be found that the program began with a small group of friends talking while eating a pizza one evening, lamenting the number of infants still not immunized. In the course of their conversation, one might have said, “If we were to create a media blitz that would get the need for immunizations into the consciousness of parents—get the need for immunizations in their face!” And the next person might have said, “In their eyes! Yea, ImmunEYEs. Let’s do it!”

Initiatives such as this start with one person creating a new approach to a problem. That person exercises power by providing the leadership or spark to create the strategy to carry out such an initiative, thus inspiring and motivating people to contribute to the effort.

Law 3: Power Is Based on a System of Ideas and Philosophy

Behaviors demonstrated by an individual as she or he exerts power reflect a personal belief system or a philosophy of life. That philosophy or ideal must be one that attracts followers, gains their respect, and rallies them to join the effort. Nurses have the opportunity to ensure that a patient’s right (versus privilege) to health care, access to preventive care, and similar values are reflected in policies and procedures.

Law 4: Power Is Exercised Through and Depends on Institutions

As an individual, one can easily feel powerless and unable to handle the complex problems facing a hospital, community, or state. But through a nursing service organization, a state nurses association, or a similar organization, that individual can garner the resources needed to magnify her or his power. The person-to-person network, the communication vehicle (usually an organization’s newsletter or journal), and the organizational structure are established for precisely this function—to support and foster changes in the health care system.

Law 5: Power Is Invariably Confronted With and Acts in the Presence of a Field of Responsibility

Actions taken create a ripple effect by speaking to the other nurses for whom nurses act and, most important, the patients for whom nurses advocate. The individual in the power position is acting on behalf of the group. Power is communicated to observers and is reinforced by positive responses. If the group thinks that its ideals are not being honored, the vacuum will be filled with the next candidate capable of the role and supported by the organization.

Another Way to Look at Power and Where to Get It

In a classic, much-referenced work, French and Raven (1959) describe five sources of power. They are (in order of importance) reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, referent or mentor power, and expert or informational power. These descriptions of power were presented in the discussion of nursing management in Chapter 10. The discussion there described the use of power within the ranks of nursing. Here, the use of power is presented as it applies to the political process, especially through political action in nursing.

The strongest source of power is the ability to reward. The best example of making use of the reward power base is the giving of money. If, for example, someone gives a decision maker financial support for a future political campaign, the recipient will feel obligated to the donor and may, from time to time, “adjust opinions” to repay these obligations! Today, because caps have been placed on campaign contributions, the misuse of this type of reward has been reduced.

An additional source of reward-based political power is the ability to commit voters to a candidate through endorsements. This illustrates the importance of having a large number of members in an organization—in other words, a large voting bloc. This reinforces the imperative for nurses to join and support nursing organizations that advocate on behalf of nurses, nursing, and quality health care.

Second in importance is the power to coerce or “punish” a decision maker for going against the wishes of an organization. The best example of this power, the opposite of reward, is the ability to remove the person from office at election time.

Third in importance is legitimate power, or the influence that comes with role and position. Influence derives from the status that society assigns individuals as a result of, for instance, inherited family money, membership in a respected profession, or a prominent position in the community. The dean in a school of nursing has a certain amount of influence just because of who he or she is. Right? A nurse’s commitment to enhancing nursing’s influence explains why nurses encourage and assist one another to achieve key decision-making positions—to build nursing’s legitimate power base.

The fourth power base is that of referent or mentor power. This is the power that “rubs off ” of influential people. When representatives of the student body talk with a faculty member about a problem they are having with a course, and they receive her or his support, the curriculum committee or dean is more likely to listen sympathetically than if the students were arguing only for themselves. The faculty member, joining with the students to solve their problem, adds to the students’ power. The wish to build this type of power encourages nurses to join coalitions, especially those including organizations with greater power than their own.

The last and weakest of the power bases is that of expert or informational power. Nurses know about health and nursing care and are thus able to impart knowledge in this area with great confidence and style. Typically, nurses communicate this authority through letters written to legislators, testimonies presented in hearings, and through other contacts made on behalf of nursing and patients. In summary, power is derived from various sources. Nurses use, with the greatest frequency and ease, the weakest of the power bases—that deriving from their expertise. Although this is an important power base, nurses must develop and exercise the other types as well. Only then will nurses realize the full extent of their potential (Critical Thinking Box 17.2).

Networking Among Colleagues

It has been said that one should never be more than two telephone calls away from a needed resource, whether it be a piece of information, a contact in a hospital in another city, or input into a decision one is about to make. The key to successful networking is consciously building and nurturing a pool of associates whose skills and connections augment your own.

As a nursing graduate, one should begin the important task of networking by selecting an instructor from nursing school who is able to speak positively about your performance during nursing school. Ask this person if she or he would be willing to write a letter of reference for your first job. If the person agrees, nurture this contact from that time onward. Keep this individual apprised of your whereabouts, your successes, and your plans for the future. This person will be an important link not only to your school but also to your future educational and career undertakings. Then, at each future work site, find a charge nurse or supervisor willing to write a reference and with whom you can maintain contact. Keep building the network throughout your career.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree