Chapter 19 Planning health promotion interventions

Overview

We have seen in Chapter 18 how needs assessment and targeting may be carried out, and the importance of carrying out this process and being clear about the context in which this is done. This chapter builds on the discussion of the first stage of planning – needs assessment – in Chapter 18. Firstly, definitions of planning are given and the reasons for planning discussed. Planning at different levels, from broad strategic planning through project planning to small-scale health education planning, is considered. The Ewles & Simnett (2003) and PRECEDE–proceed models (Green & Kreuter 2005) are reviewed in detail. Quality and audit issues and how this relates to planning are then considered.

Definitions

Reasons for planning

There has been much greater emphasis on systematic planning in recent years due to a need for greater economic accountability, more focus on targets and their achievement, and the need to include evidence as part of project development. It is particularly important for practitioners to be clear about the rationale for interventions, the goals and the approach adopted.

Health promotion planning cycle

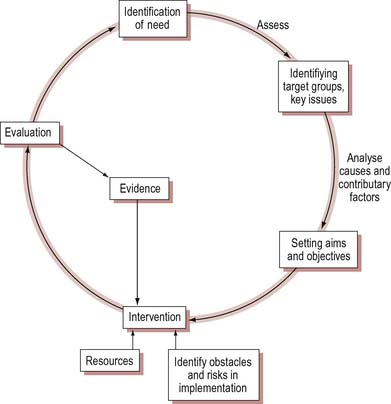

Some planning models are presented in a linear fashion. Others show a circular process to indicate that any evaluation feeds back into the process, as illustrated in Figure 19.1. This seemingly rational and simple approach describes how decisions should be made. It does not take into account that there may not be agreement on objectives or the best way to proceed and that in real life, planning is often piecemeal or incremental. There is no grand design, but circumstances dictate many small reactive decisions.

What do you think would be the best starting point for planning an intervention or programme? Why?

Think of any planned activities you have been involved with. What was the starting point? Why?

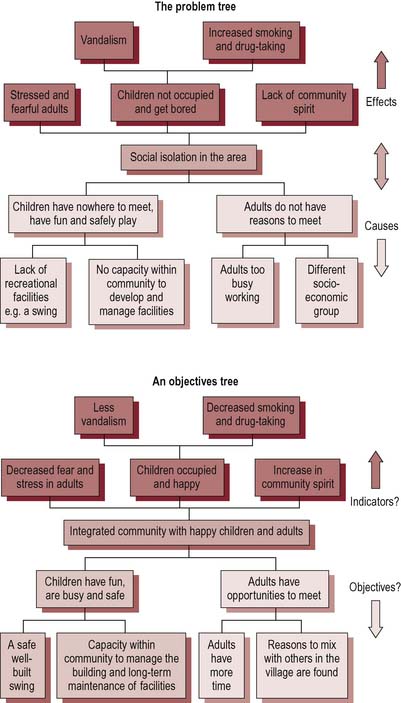

Figure 19.1 suggests that the planning cycle begins with a needs assessment through which the programme’s focus and any specific target groups may be identified. The underlying causes and contributory factors that led to the problem and the areas that will need to be addressed are then identified. Figure 19.2 shows how understanding the effects of a problem can help to identify indicators and desired outcomes from an intervention. Turning the problem, in this case antisocial activity by young people in a neighbourhood, into a positive statement gives a purpose for the intervention. Addressing the causes of the problem identifies outputs and activities. The aims and objectives can then be clearly stated. This provides a number of options for intervention and at this point many other issues come into play such as resource availability, capacity and potential obstacles. These issues will then be considered alongside any evidence of effective interventions. The actual intervention or programme and its methods can then be selected. The practicalities of implementation will need to be explored and the evaluation and monitoring plans put in place. This simple model can be applied to all levels of planning activities, from large-scale strategic planning, to middle-scale project planning and small-scale interventions with clients.

Strategic planning

Developing a local obesity strategy

Read the extract below from a local obesity strategy. What actions can you identify?

To ensure the long-term commitment of all stakeholders and to try to develop a robust action plan, an extensive consultation process has been undertaken within Torbay during the development of this strategy. Opinions have been sought with regards to both the prevention and management of obesity from stakeholders and members of the general public living in Torbay. Furthermore, a resource mapping exercise has also been undertaken. Alongside the mapping of current practice and the recording of both public and stakeholder opinion regards priorities for action, the evidence for the effectiveness of a broad spectrum of interventions was researched at length. This, alongside local and national policy, was used to help prioritise potential actions. Furthermore, those actions known to have evidence of effectiveness reaching those individuals at greatest potential risk were given largest priority … Work to improve the health of the population is by no means the sole responsibility of the health service and increasingly local responsibility for the health of communities is being shared between the agencies that make up Local Strategic Partnerships (LSPs) and with the communities themselves (Torbay Care Trust 2006).

There are several stages in developing a strategy:

These stages correspond to those of a rational planning model: assess–plan–do–evaluate.

Project planning

Broad goals might be framed in terms of:

Ewles & Simnett (2003) define project stages as:

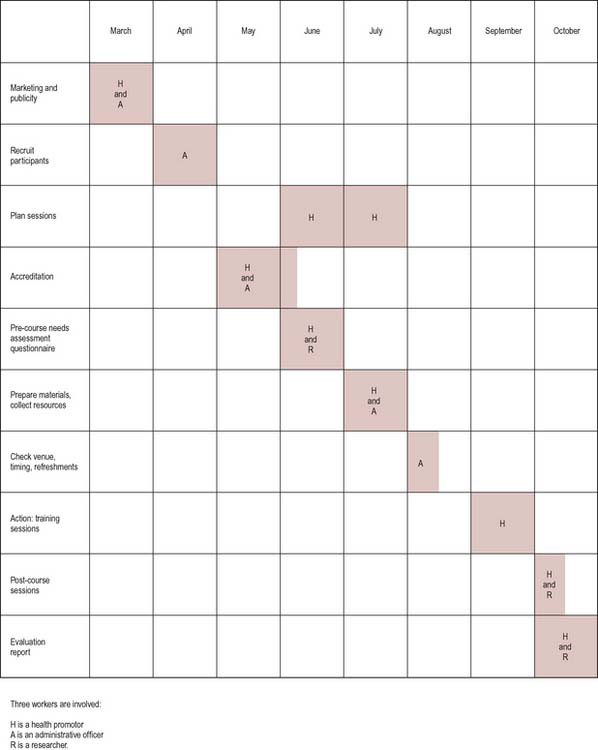

The start of the project is agreement that the project should take place, its overall aims and the allocation of a budget to support the project. Often the start is signalled by the formal adoption of a project proposal, indicating that an organization has given support for the development and implementation of a project. Specification means setting objectives and quality criteria for how the project is to be delivered. Setting objectives is considered in more detail below. Quality and audit are discussed later in this chapter. Design is the detailed planning of the training intervention. A Gantt chart (set out as an example in Figure 19.3) is a useful tool to use at this stage. A Gantt chart plots tasks and the people responsible for these tasks against a timescale in which these activities need to be undertaken. It portrays in a graphical form the interdependence of project tasks and how each single task contributes to the whole. Implementation is the project activity, e.g. training sessions. Evaluation, review and final completion report on project outcomes and assess whether objectives have been met. It is useful to have a time lag between completing the project and the final review in order to assess long-term as well as immediate outcomes.

BOX 19.1

BOX 19.1

BOX 19.2

BOX 19.2

BOX 19.3

BOX 19.3 BOX 19.4

BOX 19.4

BOX 19.5

BOX 19.5