Chapter 9 Planning and evaluation

Introduction

This chapter builds on the presentation and analysis of public health policies in Chapter 3. Public health planning is the means to maximise these and other policy aspirations. For example, integrated planning and preparation is in place to ensure all emergency health services, hospitals and population/public health units are prepared for a quick and efficient response to any major infectious disease outbreak, such as ‘bird flu’ (avian influenza). The emergency response to the Queensland floods and cyclone Yasi in 2011, and the bush fires in Victoria February 2009, demonstrates the value of a coordinated response by emergency health professionals, government officials, media and volunteers. You will develop and design an array of plans as a health professional; these can be community-based ‘public health’ programmes, such as a physical activity or nutrition education programmes, and radio and/or media campaigns. Examples include national and state plans for vaccinating children against infectious diseases; the promotion of dental health for children in schools; and screening programmes for cervical, breast and bowel cancer. If you are a nurse in a hospital, you will be developing patient care plans.

Each government level designs programmes to enhance the quality of life of their constituents. Local governments (councils) attempt to create healthy local environments to promote and protect the quality of life of residents. They plan parks for recreation, construct traffic-calming devices near schools to prevent accidents, build shade structures and walking paths, and even embed draughts/chess squares in picnic tables for people to sit and play. Environmental health officers ensure food safety in restaurants and measure water quality. The federal and state governments produce plans that protect and promote health through various policy and programme initiatives and innovations, as presented in Chapter 3.

Planning and evaluation in public health

As we saw in Chapter 2, the roots of public health planning go back to some of the earliest sanitary control measures; ‘these were planned responses to the work of early epidemiology and the mysteries of communicable diseases’ (Blum 1974 in Lenihan 2005 p 381). Without good planning, we would not be effective in preventing disease, and promoting and restoring health in the community. Lenihan (2005) claimed there are three models that have typified planning in public health practice. The first is problem/programme planning and community assessment. These ‘are well established components of health education with a focus on improving the health of defined population groups …’ (Lenihan 2005 p 382). The second is advocacy planning, where ‘the planner becomes a change agent to raise awareness and mobilise a population group to solve a community problem or develop a programme’ (Lenihan 2005 p 382). Advocacy planning adds community participation to the planning process, but planners or health professionals often control the process through technical aspects of planning. The third is strategic planning, which connects public health planning practice to current and potential partners needed to meet future challenges (Lenihan 2005). Often this happens through senior government officials and politicians, for example, planning to manage potential health emergencies and disasters. Common to each of these models is an identified public health need, and adequate financial and human resources, to ensure successful programme development, implementation, evaluation and sustainability. The National Chronic Disease Strategy could be described as strategic planning – as a policy perspective (see Chapter 3).

Activity

Models of planning

Public health planning models help us to organise our thinking about what steps we need to follow to achieve our desired goals. They can be simple or sophisticated in design. Fleming and Parker (2007) identify a diverse number of planning models, for example, Bartholomew et al. (2001) developed a planning model called Intervention Mapping. The word ‘intervention’ is sometimes used interchangeably with the term ‘programme’. Intervention mapping outlines the explicit steps you would use to plan a community-based public health programme, particularly where your aim is to influence behaviour change. It considers the evidence and the use of behaviour change theories from previous successful ‘interventions’ as a starting point, so that there is an increased likelihood of success. Intervention mapping has been applied successfully to large-scale health promotion programmes in communities, as has the next model.

Green & Kreuter (1991) developed the PRECEDE model (Predisposing, Reinforcing, Enabling Constructs in Educational/Environmental Diagnosis and Evaluation). This was expanded to PROCEED to include Policy, Regulatory and Organisational Constructs in Education and Environmental Development (Green & Kreuter 2005). The strength of this model is its recognition of various starting points for planning. Again, planners are encouraged to be systematic and analytical in how to make changes to a community health problem. This model diagnoses the influences of both behavioural and environmental factors on community health. Questions are asked, such as what are the predisposing factors that may facilitate or hinder behaviour change? For example, does the community lack knowledge about the impact of smoking on health? What can reinforce a behaviour change once it is adopted? And what can enable behavioural or community change? For instance, smoke-free environments may reinforce non-smoking behaviour. Both the Intervention Mapping and the PRECEDE/PROCEED models have a focus on rational planning, that is, planning that is well informed, addresses a well-defined problem and has adequate resources to ensure a successful outcome. Dignan and Carr (1987) suggest that plans should provide answers to three basic questions: ‘What are my goals and objectives, what do I need to do in order to achieve these objectives, and how can I establish whether I have met my objectives?’ (Dignan & Carr 1987 p 257 cited in Ewles & Simnett 1999). You can utilise any one of these models or adapt or choose the aspects that are appropriate for your own specific health profession. Let’s talk through the Ewles & Simnett (1999) model. You can obtain further details on each of these models by reading the authors’ books on the reference list.

This is a seven-stage model that can be used as a template for programme planning and action (Ewles & Simnett 1999). It is a broad guideline of the steps taken in programme planning, and is useful in its simplicity:

The first step in the Ewles and Simnett (1999) model is to identify needs and priorities. So how do we identify needs? And what kinds of needs are there? We summarise needs assessment next. Knowing various types of ‘needs’ is important knowledge for all health professionals.

Identifying needs and priorities

Public health plans are based on identifying and assessing needs. These needs may exist or be anticipated. For example, emergency and disaster plans to protect the public are developed in anticipation of events. And, as public health information becomes more sophisticated and robust, policy makers may have already identified the health issues, as we discussed in Chapter 3. Our national health policies are based on the evidence of need, and there are numerous data sources available to assist health professionals to plan effective programmes, such as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). See the end of this chapter for their websites.

How are needs identified? Katz et al. (2000) identify four different ways of defining needs. This is very similar to the explanations presented below by Hawe et al. (1990). Bradshaw (1972 in Katz et al 2000) identified a ‘taxonomy of needs’; a taxonomy is simply a categorisation. There are commonly four types of need in public health: normative, comparative, expressed and felt. Additionally, there are other ways to gauge needs, such as rapid appraisals and the use of epidemiological evidence.

Activity

Beginning your programme plan

The second stage of Ewles and Simnett’s (1999) model is writing goals, objectives and strategies, identifying a target group (a population or subpopulation), identifying resources and planning an evaluation. A programme logic model is one way of doing this.

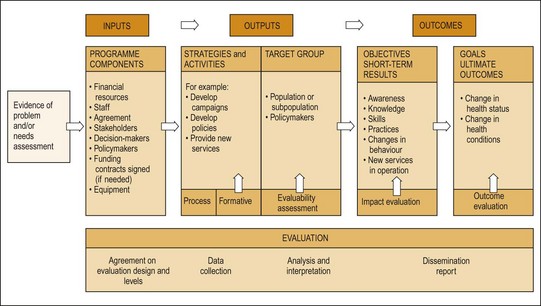

A programme logic model is a diagrammatic representation of the logical connections among the elements of a programme, including its goals and objectives, activities, impact and outcomes, and its evaluation plan. All those with a vested interest in the outcomes of the programme would ideally be engaged in developing the programme logic model. Thus, a programme logic model can be displayed in a flow chart, map or table, to portray the sequence of steps leading to programme results. See Figure 9.1 for an example of a programme logic model.

Fig. 9.1 Programme logic model.

(Source: Parker 2007 adapted from Taylor-Powell 2005. The UW-Extension Logic Model is owned by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as the UW-Extension, Cooperative Extension)

Be very clear about defining your ‘stakeholders’. These are the people who are often the funders of your programme, but your stakeholders can be community members or patients for whom the programme is intended. They can be government or non-government officials or staff from a granting body (Rootman et al. 2001).

Writing goals and objectives

Goals and objectives need to be written specifically so they can be measured (Hawe et al. 1990). A goal is written to describe the desired change in the health or behaviour of a group, for example, the reduction in obesity in Year 9 and 10 teenagers, by 20% over 3 years.

Objectives are specific and should be linked to the goals, and be realistic and evidence based. This means that you can confidently predict that your objectives are logical and are linked to the evidence base. For example, a goal could be related to nutrition education, for instance, ‘the proportion of children who can distinguish healthy foods from overly fatty foods’ (Hawe et al. 1990 p 43). An aid to writing objectives is that they should be SMART, that is:

Identifying a target group

As public health is about populations, it is common to identify the target group as ‘everyone’, irrespective of age, socioeconomic status, income or education. Measuring the impact of such programmes in large population groups is difficult, so being clear and precise about the profile of your population is important. There is evidence that modifying people’s health status through the use of public health campaigns, especially those that use multiple methods (legislative, media campaigns, advocacy, group and individual education), can take up to 5 years (Green & Anderson 1986). See Chapter 13 for the discussion on tobacco control in Australia and how diverse strategies, sustained over many years, were used to achieve the goals.