Physiologic Changes

Objectives

1. Describe the most common structural changes observed in the normal aging process.

2. Discuss the impact of normal structural changes on the older adult’s self-image and lifestyle.

3. Describe the most commonly observed functional changes that are part of the normal aging process.

4. Discuss the impact of normal functional changes on the older adult’s self-image and lifestyle.

5. Identify the most common diseases related to aging in each of the body systems.

6. Differentiate between normal changes of aging and disease processes.

7. Discuss the impact of age-related changes on nursing care.

Key Terms

carcinoma (kăr-s -NŌ-mă) (p. 35)

-NŌ-mă) (p. 35)

cardiomegaly (kăhr-dē-ō-MĔG-ă-lē) (p. 47)

cataracts (KĂT-ă-răkts) (p. 64)

dementia (dĕ-MĔN-shē-ă) (p. 58)

diverticulosis ( l-vĕr-t

l-vĕr-t k-ū-LŌ-s

k-ū-LŌ-s s) (p. 53)

s) (p. 53)

glaucoma (glă-KŌ-mă) (p. 64)

hypothyroidism ( l-pōT

l-pōT I-royd-

I-royd- zm) (p. 60)

zm) (p. 60)

ischemic ( s-KĒ-m

s-KĒ-m k) (p. 46)

k) (p. 46)

nystagmus (n s-TĂG-mŭs) (p. 66)

s-TĂG-mŭs) (p. 66)

orthostatic hypotension (ŏr-thō-STĂT- k

k  l-pō-TĔN-shŭn) (p. 45)

l-pō-TĔN-shŭn) (p. 45)

osteoporosis (ŏs-tē-ō-pă-RŌ-s s) (p. 39)

s) (p. 39)

seborrheic dermatitis (sĕb-ō-RĒ- k dĕr-mă-

k dĕr-mă- I-t

I-t s) (p. 36)

s) (p. 36)

seborrheic keratosis (sĕb-ō-RĒ- k kĕr-ă-TŌ-s

k kĕr-ă-TŌ-s s) (p. 33)

s) (p. 33)

senile lentigo (SĒ- ll lĕn-

ll lĕn- I-gō) (p. 33)

I-gō) (p. 33)

senile purpura (SĒ- ll PŪR-pū-ră) (p. 34)

ll PŪR-pū-ră) (p. 34)

xerosis (zĕr-Ō-s s) (p. 34)

s) (p. 34)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

The changes in body function that occur with aging are not random and do not develop suddenly or without warning. Rather, they are part of a continuum that begins the moment life begins. From the moment of conception, tissues and organs develop in an orderly manner. When fully developed, these organs and tissues perform specific functions and interact together in a predictable way. Throughout life, human growth and development occur methodically.

Early in life, the physical changes are dramatic. In only 9 months of gestation, the human organism develops from two almost invisible cells into a unique, functioning individual measuring approximately 20 inches in height and usually weighing between 6 and 9 pounds. For the next 13 to 15 years, rapid physical growth continues. By approximately age 18, the human body reaches full anatomic and physiologic maturity.

The peak years of physiologic function last from the late teens through the thirties—the so-called prime of life. Physiologic changes are still occurring during this time, but they are subtle and not easily recognized. Because these changes do not happen as rapidly or as dramatically as do those that occur early in life, they are more likely to be ignored.

As a person moves into his or her fifth and sixth decades of life, these physiologic changes become more apparent. In the seventh and eighth decades and beyond, they are significant and no longer deniable.

It is important to recognize that although age-related changes are predictable, the exact time at which they occur is not. Just as no two individuals grow and develop at exactly the same rate, no two individuals show the signs of aging at the same time. There is wide person-to-person variation in when—and to what degree—these changes occur. Heredity, environment, and health maintenance significantly affect the timing and magnitude of age-related changes. Some people are chronologically quite young but appear old. The most severe cases of this occur in a rare condition called progeria. When they are only 8 or 9 years of age, children with progeria have the physiology and appearance of 70-year-olds. At the other extreme, there are persons in their sixties, seventies, and even older who are vigorous and appear much younger than their chronologic age. Most people show the signs of aging at a rate somewhere between these two extremes.

We can observe many normal changes in the body’s physical structure and function during the aging process. There are also changes that indicate the onset of disease or illness. Nurses are expected to be able to tell the difference between normal changes and abnormal changes that signify a need for medical or nursing intervention. To identify these differences, nurses must have a good understanding of the normal structures and functions of the body. This knowledge should help nurses understand how normal and abnormal changes affect the day-to-day functional abilities of older adults. As nurses, we must be aware of the physical changes that are likely to occur, assess each individual to determine the extent to which these changes have occurred, and then make our care plans in response to that specific person’s needs.

Some diseases are more commonly seen with advanced age. Most older adults experience one or more chronic conditions. The leading causes of disability over age 65 are heart disease, stroke, arthritis, hypertension, accidents, diabetes mellitus (DM), cancer, and diseases of the ears and eyes. Currently, the five leading causes of death among older adults are (1) heart disease, (2) cancer, (3) cardiovascular disease (primarily stroke), (4) pneumonia, and (5) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

It is essential for nurses to learn that each aging person, just like each younger person, is unique. The type and extent of changes seen with aging are specific and unique to each person. Nurses must avoid falling into the trap of stereotyping older adults. Stereotyping is dangerous because it leads us to accept as inevitable some changes that are not inevitable. Stereotyping can also cause us to mistake early signs of disease as a part of aging.

The integumentary system

The integumentary system, which includes the skin, hair, and nails, undergoes significant changes with aging. Because many of these structures are visible, changes in this system are probably the most obvious and are evident to both the aging individual and others.

The epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin, is an important structure that provides protection for internal structures, keeps out dangerous chemicals and microorganisms, functions as part of the body’s fluid regulation system, and helps regulate body temperature and eliminate waste products. It also contains melanocytes that produce the pigment melanin, which provides protection from ultraviolet radiation.

The dermis contains collagen and elastin fibers, which give strength and elasticity to the tissues. The sebaceous (oil-producing) and eccrine (sweat-producing) glands are located in the subcutaneous tissue, as are the hair and nail follicles and the sensory nerve receptors. Hair and nails are composed of dead keratinized cells. Hair pigment, or color, is related to the amount of melanin produced by the follicle and, like skin pigmentation, is hereditary. Nails are rigid structures that protect the sensitive, nerve-rich tissue at the tips of the fingers and toes. Nails also aid dexterity in fine finger manipulation.

Subcutaneous tissue consists of areolar connective tissue, which connects the skin to the muscles, and adipose tissue, which provides a cushion over tissue and bone. Subcutaneous tissue provides insulation to regulate body temperature. It is here that white blood cells (WBCs) are available to protect the body from microbial invasion through the skin. Blood vessels in the subcutaneous tissue supply the tissue with nourishment and assist in the process of heat exchange. These superficial blood vessels dilate or constrict as needed to release heat or to conserve heat lost through convection.

Expected Age-Related Changes

With aging, the epidermis becomes more fragile, increasing the risk for skin damage such as tears, maceration, and infection. Rashes caused by contact with chemicals, such as detergents or cosmetics, are increasingly common in older individuals. Skin repairs more slowly in older than in younger individuals, increasing the risk for infection.

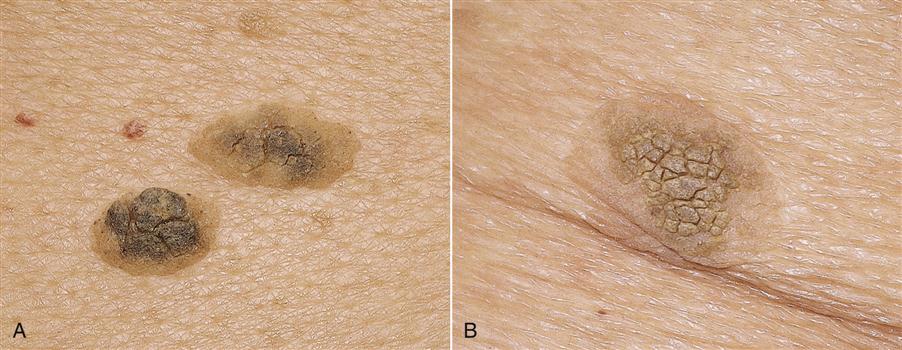

Melanocyte activity declines with age, and in light-skinned individuals, the skin may become very pale, making older individuals more susceptible to the effects of the sun. Clusters of melanocytes can form areas of deepened pigmentation, a condition called senile lentigo; these areas are often referred to as age spots or liver spots and are most often seen on areas of the body that are most exposed to sunlight. In a condition called seborrheic keratosis, slightly raised, wartlike macules with distinct edges appear (Figure 3-1). These lesions, which can range in color from light tan to black, are most often observed on the upper half of the body, and they may cause discomfort and itching. Skin tags, or cutaneous papilloma, are small, brown or flesh-colored projections of skin that are most often observed on the necks of older adults.

Aging results in decreased elastin fibers and a thinner dermal layer (Table 3-1). With the loss of elasticity, the skin starts to become less supple. “Crow’s feet,” or wrinkles, develop. Skin that is very dry or that has had excessive exposure to sunlight or harsh chemicals is more likely to wrinkle at a younger age. Hair color tends to fade or “gray” because of pigment loss, and hair distribution patterns change. Color changes, and hair loss patterns tend to be hereditary. The hair on the scalp, pubis, and axilla tends to thin in both men and women. Hairs in the nose and ears often become thicker and more noticeable. Some women experience the growth of facial hair, particularly after menopause. Fingernails grow more slowly, may become thick and more brittle, and ridges or lines are commonly observed. Toenails may become so thick that they require special equipment for trimming. Sweat gland function decreases, and thus the amount of perspiration decreases. This results in heat intolerance because the body’s cooling system through the process of evaporation is less efficient.

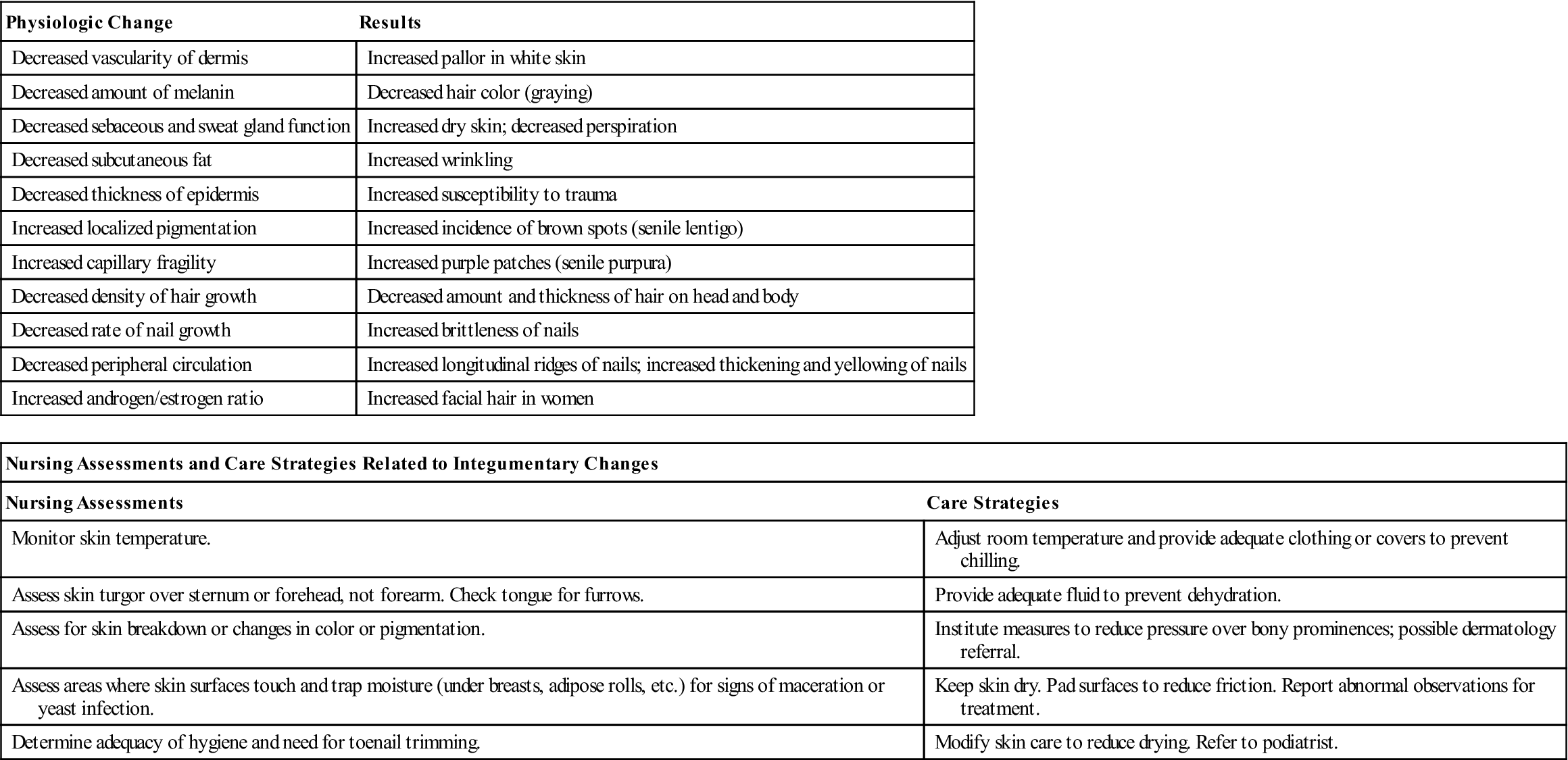

Table 3-1

Integumentary Changes Associated With Aging

| Physiologic Change | Results |

| Decreased vascularity of dermis | Increased pallor in white skin |

| Decreased amount of melanin | Decreased hair color (graying) |

| Decreased sebaceous and sweat gland function | Increased dry skin; decreased perspiration |

| Decreased subcutaneous fat | Increased wrinkling |

| Decreased thickness of epidermis | Increased susceptibility to trauma |

| Increased localized pigmentation | Increased incidence of brown spots (senile lentigo) |

| Increased capillary fragility | Increased purple patches (senile purpura) |

| Decreased density of hair growth | Decreased amount and thickness of hair on head and body |

| Decreased rate of nail growth | Increased brittleness of nails |

| Decreased peripheral circulation | Increased longitudinal ridges of nails; increased thickening and yellowing of nails |

| Increased androgen/estrogen ratio | Increased facial hair in women |

| Nursing Assessments and Care Strategies Related to Integumentary Changes | |

| Nursing Assessments | Care Strategies |

| Monitor skin temperature. | Adjust room temperature and provide adequate clothing or covers to prevent chilling. |

| Assess skin turgor over sternum or forehead, not forearm. Check tongue for furrows. | Provide adequate fluid to prevent dehydration. |

| Assess for skin breakdown or changes in color or pigmentation. | Institute measures to reduce pressure over bony prominences; possible dermatology referral. |

| Assess areas where skin surfaces touch and trap moisture (under breasts, adipose rolls, etc.) for signs of maceration or yeast infection. | Keep skin dry. Pad surfaces to reduce friction. Report abnormal observations for treatment. |

| Determine adequacy of hygiene and need for toenail trimming. | Modify skin care to reduce drying. Refer to podiatrist. |

A decrease in the function of sebaceous and sweat gland secretion increases the likelihood of dry skin, or xerosis (Figure 3-2). Dry skin is probably the most common skin-related complaint among older adults, particularly when it is accompanied by itching, or pruritus. This problem is often more severe on the lower extremities because of diminished circulation.

The walls of the capillaries become increasingly fragile with age and may hemorrhage, leading to senile purpura, the red, purple, or brown areas commonly seen on the legs and arms. By 70 years of age, the body has approximately 30% fewer cells than at age 40. The remaining cells enlarge, so body mass appears approximately the same. Total body fluid decreases with age. Plasma and extracellular volume remain somewhat constant, but intracellular fluid decreases. This loss of intracellular fluid increases the risk for dehydration. Tissue changes include a decrease in subcutaneous tissue that is visible in the eye orbits, hollows in the supraclavicular space, and sagging of breasts and neck tissue.

Common Disorders Seen with Aging

Basal Cell Carcinoma and Melanoma

It is important to distinguish normally occurring changes in the skin from lesions that may be precancerous or cancerous. Cases of basal cell carcinoma are commonly observed in older adults who have spent significant amounts of time in the sun. By age 70 approximately 20% of white, non-Hispanic men have developed a non-melanoma cancer. Male senior citizens are also most at risk for melanoma, a potentially deadly form of skin cancer due to its ability to metastasize. In 2009 more than 8,000 deaths were attributed to melanoma.

The unusual appearance of moles should be suspected to be melanoma. Irregular shapes, irregular borders, changes in color, changes in size or symptoms, such as itchiness or bleeding, are all considered to be abnormal. Elderly men, in particular, should be taught to self-screen for changes in the skin. Suspicious changes should be documented and reported so that it can be examined promptly by a physician. Early diagnosis and treatment is effective at prolonging life.

Pressure Ulcers

Shrinkage in the cushion provided by subcutaneous tissue along with vascular changes places the older adult at increased risk for pressure ulcers (i.e., breakdown of the skin and tissues located over bony prominences) (see Figure 3-3). This is a significant problem for immobilized people such as those who are bedridden or confined to wheelchairs. Special precautions to prevent this type of problem are discussed in Chapter 17.

A, Early-stage pressure ulcers, or stage I lesions, are commonly dismissed as minor abrasions because their primary attribute is nonblanchable erythema.

B, Stage II ulcer, which is characterized by some skin loss, may be difficult to identify accurately because of its resemblance to a blister or abrasion.

Inflammation and Infection

Changes in the integumentary system increase the older adult’s risk for skin inflammation and infection. Skin inflammation and infection often occur on visible surfaces of the body such as the face, scalp, and arms, making the conditions distressing to the older adult.

Common types of inflammation include rosacea and various forms of dermatitis. Rosacea appears as redness, dilated superficial blood vessels, and small “pimples” on the nose and center of the face (Figure 3-4). It may spread to cover the cheeks and chin. Left untreated, it can lead to swelling and the enlargement of the nose or to conjunctivitis. There is no known cause for this disorder, but it is most common in postmenopausal women, people who flush easily, and individuals taking vasodilating medications. Treatment of vasodilation includes lifestyle modification such as avoidance of triggers such as stressful situations, extreme heat, sun exposure, spicy foods, and alcoholic beverages. In addition oral and topical medications or light and laser treatments may provide some benefits.

Several forms of dermatitis are common in older adults, including contact, allergic, and seborrheic dermatitis. Contact and allergic dermatitis appear as rashes or inflammation that is either localized to certain areas of the body or generalized (Figure 3-5). Clues to the causative substance are gained from the unique pattern presented on each individual. Identification of the particular irritant may be difficult because of the number of chemicals, drugs, and other substances to which an individual is exposed. Treatment consists of avoiding the offending substance.

Seborrheic dermatitis is an unsightly skin condition characterized by yellow, waxy crusts that can be either dry or moist (Figure 3-6). Caused by excessive sebum production, seborrheic dermatitis can occur on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelids, ears, axilla, breasts, groin, and gluteal folds. There is no known cure, but treatment with special shampoos and lotions helps control the problem.

Infectious diseases of the skin and nails commonly seen in older adults include herpes zoster (also called shingles); fungal, yeast, and bacterial infections; and infestation with scabies (mites). Each of these diseases has a unique cause, characteristic appearance, and specific treatment that are beyond the scope of this text.

Hypothermia

The decrease in the amount of subcutaneous tissue reduces the older adult’s ability to regulate body temperature. Very thin older adults lose the insulation provided by subcutaneous and adipose tissue. This loss of insulation is most likely to result in hypothermia if the person is exposed to an environment that is too cold.

The musculoskeletal system

The musculoskeletal system performs many functions. The bones of the skeleton provide a rigid structure that gives the body its shape. The red bone marrow in the cavities of spongy bones produces red blood cells (RBCs), platelets, and WBCs. Structures such as the ribs and pelvis protect easily damaged internal organs. The muscles provide a power source to move the bones. The combined functions of bones and muscles allow free movement and participation in the activities necessary to maintain a normal life.

Bones

Bone consists of protein and the minerals calcium and phosphorus. Calcium is necessary for bone strength, muscle contraction, myocardial contraction, blood clotting, and neuronal activity. It is normally obtained by eating dairy products and dark-green leafy vegetables. Vitamin D is needed for the absorption of calcium and phosphate through the small intestine; vitamins A and C are needed for ossification, or bone matrix formation.

For the long bones to remain strong, adequate dietary intake of these nutrients is important. However, the dietary intake of minerals alone does not maintain bone strength. It is also necessary to apply stress to the long bones to keep the minerals in the bones. This needed stress is best provided by weight-bearing activities such as standing and walking. The calcium that is needed for clotting and nerve and muscle functions is constantly being withdrawn from the bone and moved into the bloodstream to maintain consistent blood levels. Calcium is normally redeposited in the bone at an equal rate, replacing the calcium that is lost. As long as this movement of calcium is in balance, the bone remains strong.

Hormones also play an important role in bone maintenance. Calcitonin, which is produced by the thyroid gland, slows the movement of calcium from the bones to the blood and lowers the blood calcium level. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) increases the movement of calcium from the bones to the blood and increases the blood calcium level. PTH also increases the absorption of calcium from the small intestine and kidneys, thus further increasing the blood calcium level. Insulin and thyroxine aid in the protein synthesis and energy production needed for bone maintenance. Estrogen and testosterone, produced by the ovaries and testes, respectively, help retain calcium in the bone matrix.

Vertebrae

The spinal column consists of a series of small bones, called vertebrae, that stack up to form a strong, flexible structure. The spinal column supports the head and allows for flexible movement of the back. The segments of the spinal column consist of cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral vertebrae. The muscles that move the back connect at bony processes that protrude from each vertebra. The spinal cord, the nerve tissue that extends downward from the brain, passes through the vertebral canal, which runs through an opening in each vertebra. The bones of the spinal column protect this nerve tissue from injury.

Fibrous pads, called intervertebral disks, are located between the vertebrae and cushion the impact of walking and other activities.

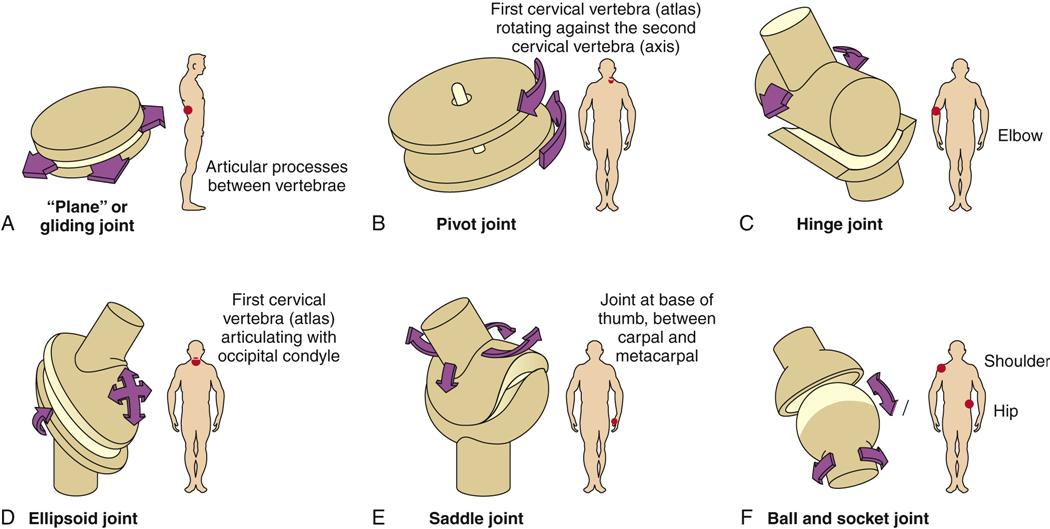

Joints

Joints are the places where bones meet. The freely moving synovial joints are lined with cartilage, which allows free movement of the joint surfaces. Many of these joints contain a bursa, which is a fluid sac that provides lubrication to enhance joint mobility (Figure 3-7).

Tendons and Ligaments

Tendons are structures that connect the muscles to the bone, and ligaments are structures that connect bones to other bones.

Muscles

There are three types of muscle tissue in the body: cardiac muscle, smooth muscle, and skeletal muscle. Cardiac muscle, located in the heart only, is responsible for the pumping action of the heart that maintains the blood circulation. Smooth muscle is found in the walls of hollow organs such as the blood vessels, stomach, intestines, and urinary bladder. Because cardiac and smooth muscle normally cannot be stimulated by conscious effort, they are called involuntary muscles.

Skeletal muscle accounts for the largest amount of muscle tissue in the body. The major function of skeletal muscle is to move the bones of the skeleton. Because their actions can be controlled by conscious effort, skeletal muscles are considered voluntary muscles. Muscles are connected to bones by tendons. Contraction or relaxation of muscles causes the bones to move. Controlled and coordinated movement of bones and muscles allows us to perform the variety of movements required for activities of daily living. Special effort and practice allow us to perform special activities such as dancing, playing sports, and playing the piano.

The amount of muscle mass and the type of muscle development differ greatly among individuals. Men normally have larger muscles, or more muscle mass, than do women, particularly in the muscles of the upper body. The male hormone testosterone stimulates muscle development. In both men and women, the largest and strongest skeletal muscles are found in the legs and upper arms; the smallest and weakest are located in the lower back.

Muscle tissue is normally in a state of slight contraction. This muscle tone is necessary to support the head, to keep the spine erect, and to perform any controlled movement. Muscle mass is built and muscle tone is maintained by means of exercise. There are two general types of exercise: isometric exercise, which involves muscle contraction without body movement, and isotonic exercise, which involves muscle contraction with body movement. Isometric exercise helps maintain muscle tone and strength but does little to increase muscle size. Isotonic exercise maintains muscle tone and strength and increases muscle mass if it is done repetitively. Aerobic exercise is isotonic exercise that occurs for 30 minutes or longer. Aerobic exercise strengthens the skeletal, cardiac, and respiratory muscles. People who lead inactive or sedentary lifestyles suffer from the lack of isotonic exercise. Regardless of age, unless people undertake an exercise program, they manifest poor muscle development and strength.

Muscle movement is controlled by impulses from the parietal lobes of the cerebrum and is coordinated by impulses from the cerebellum. Muscle sense is a term used to describe the brain’s ability to recognize the position and action of the muscles without conscious effort. Receptor cells in the muscles, called proprioceptors, send information to the brain that enables it to integrate all body movements. This coordinative function of the brain allows us to walk, bend, or eat without consciously thinking about all of the separate movements and feeling all of the different positions.

Muscles need energy to function. The most abundant source of muscular energy is glycogen. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the direct energy source for muscular contraction, is a product of glycogen metabolism. Glycogen is first broken down into glucose. During cell metabolism, glucose interacts with oxygen transported in the bloodstream by hemoglobin or oxygen stored in the muscle fibers as myoglobin. This reaction involves the production of ATP, heat, water, and carbon dioxide. If muscle fibers do not receive enough oxygen, glucose may not be oxidized completely, and a chemical intermediate, lactic acid, is produced. Elevated levels of lactic acid may result in muscle fatigue and soreness.

Expected Age-Related Changes

The major bone-associated change related to aging is the loss of calcium (Table 3-2). This change begins between 30 and 40 years of age. With each successive decade, the skeletal bones become thinner and relatively weaker. Women lose approximately 8% of skeletal mass each decade, whereas men lose approximately 3%. Decalcification of various parts of the skeleton, including the epiphyses, vertebrae, and jaw bones, can result in increased risk for fracture, loss of height, and loss of teeth.

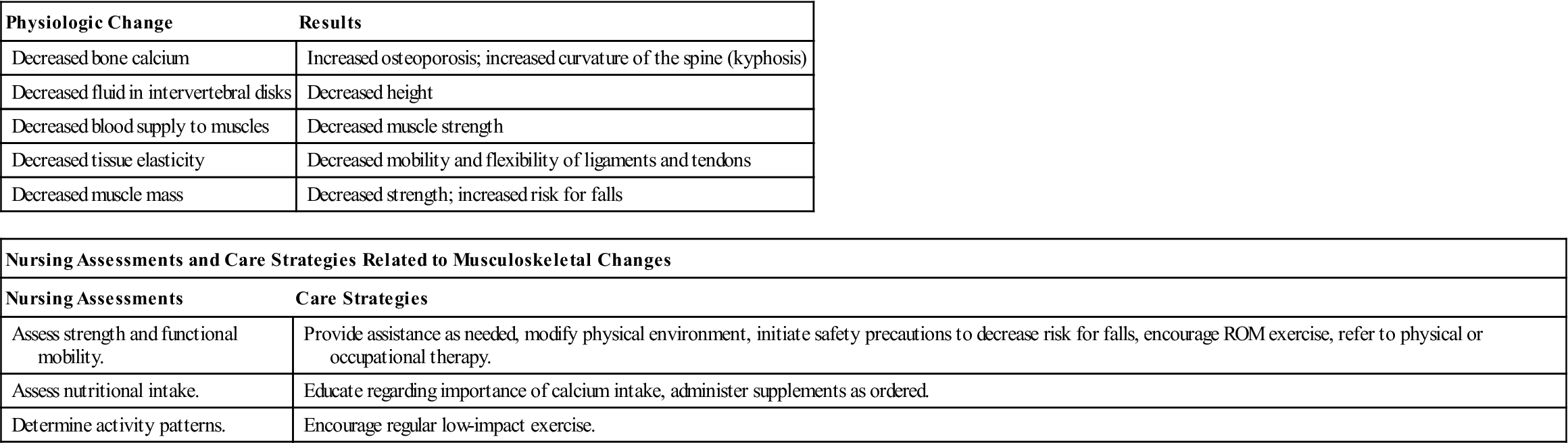

Table 3-2

Musculoskeletal Changes Associated With Aging

| Physiologic Change | Results |

| Decreased bone calcium | Increased osteoporosis; increased curvature of the spine (kyphosis) |

| Decreased fluid in intervertebral disks | Decreased height |

| Decreased blood supply to muscles | Decreased muscle strength |

| Decreased tissue elasticity | Decreased mobility and flexibility of ligaments and tendons |

| Decreased muscle mass | Decreased strength; increased risk for falls |

| Nursing Assessments and Care Strategies Related to Musculoskeletal Changes | |

| Nursing Assessments | Care Strategies |

| Assess strength and functional mobility. | Provide assistance as needed, modify physical environment, initiate safety precautions to decrease risk for falls, encourage ROM exercise, refer to physical or occupational therapy. |

| Assess nutritional intake. | Educate regarding importance of calcium intake, administer supplements as ordered. |

| Determine activity patterns. | Encourage regular low-impact exercise. |

The intervertebral disks shrink as the thoracic vertebrae slowly change with aging. This results in a condition called kyphosis, which gives the older adult a stooped or hunchback appearance, with the head dropping forward toward the chest. The combination of disk shrinkage and kyphosis results in loss of overall height. A person can lose as much as 2 inches of height by age 70. People who are concerned about their appearance find these changes disturbing because clothing no longer fits properly, and it is increasingly difficult to find flattering styles.

Connective tissues tend to lose elasticity, leading to restriction of joint mobility. Loss of flexibility and joint mobility begins as early as the teen years and is common with aging. Regular stretching exercises can help slow or even reverse flexibility problems.

Muscle tone and mass typically decrease with aging, and these decreases are directly related to decreased physical activity and exercise. People of all ages who exercise regularly have better muscle mass and tone. Hormonal changes, particularly the decrease in testosterone level, tend to reduce muscle mass in aging men. Reduction in blood supply to the muscles as a result of aging or disease can lead to changes in muscle function. Less glycogen is stored in aging muscles, thereby decreasing the fuel available for muscle contraction. Any condition that restricts oxygen availability (e.g., anemia and respiratory problems) can lead to an excessive production of waste products such as lactic acid and carbon dioxide. This can increase the incidence of muscle spasms and muscle fatigue with minimal exertion. Decreased endurance and agility may result from a combination of these factors. Neuronal changes in the areas of the brain responsible for muscle control can result in alterations of muscle sense, which may be observed in older adults as an unsteady gait and impairment of other activities that require muscular coordination.

As a person ages, muscle mass decreases, and the proportion of body weight resulting from fatty, or adipose, tissue increases. This is significant in the administration of medications. Intramuscular injection sites may not be as well muscled, and fatty tissue tends to retain medication differently than does lean tissue. Absorption and metabolism of drugs can be significantly different from those in younger persons.

Common Disorders Seen with Aging

Osteoporosis

Excessive loss of calcium from bone combined with insufficient replacement results in osteoporosis. Currently, 55% or more of Americans over age 50 have decreased bone density, and more than 10 million have osteoporosis. This disorder is projected to become even more common as the population ages. Osteoporosis is characterized by porous, brittle, fragile bones that are susceptible to breakage. Spontaneous fracture of the vertebrae or other bones can occur in the absence of obvious trauma. In fact, spontaneous hip fractures may lead to a fall, rather than the fall leading to the hip fracture. Simple falls or other traumas are more likely to result in fractures in people who have osteoporosis. Common fracture sites include the hip (usually the neck of the femur), ribs, clavicle, and arm (when trying to break a fall). Factors that increase the risk for osteoporosis include the following:

• Family history of osteoporosis

• Poor nutrition (diet low in calcium and vitamin D)

• Malabsorption disorders such as celiac disease

• Menopause (low estrogen levels)

• Excessive alcohol consumption

• Hormonal imbalances (hyperthyroidism and hyperparathyroidism)

• Long-term use of medications, including phenytoin (Dilantin), heparin, and oral corticosteroids

Osteoporosis is best prevented and treated by lifestyle modifications and medications. Lifestyle modifications include a well-balanced diet with adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D, regular exercise, smoking cessation, and restriction of alcohol intake. Calcium and vitamin D supplements are commonly necessary for individuals who do not consume adequate amounts of these nutrients. Medications that increase bone strength and density are often prescribed. These include alendronate (Fosamax), risedronate (Actonel), ibandronate (Boniva), raloxifene (Evista), and calcitonin (Calcimar). Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has beneficial effects on bone density but also brings increased risk for heart attack, blood clots, stroke, and breast cancer. Use of hormonal therapy is controversial and requires a candid risk/benefit analysis between the patient and physician.

Degenerative Joint Disease

Osteoarthritis

The incidence of osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis, increases with age. Osteoarthritis is estimated to affect 43 million adults in the United States and to cost $86 billion annually in treatment costs. By age 70, as many as 70% of adults will experience some degree of disability or discomfort from this disorder. Although common with aging, osteoarthritis is not a normal part of aging. It affects men and women equally, although men are usually affected at a younger age. The cause of osteoarthritis is unknown; however, chemical, nutritional, genetic, hormonal, and mechanical factors are believed to play a role. People employed in jobs that involve placing a high amount of physical stress on certain joints are likely to experience changes in those joints later in life. After years of normal joint use, the cartilage on the bones’ articulating surfaces thins and begins to wear out. Bony particles or spurs (osteophytes) may form within the joint, causing pain, swelling, and restriction of movement in affected joints. Heberden’s nodes, which are caused by abnormal cartilage or bony enlargement, may be seen in the distal joints of the fingers. Pain may occur with activity or exercise of the affected joints and may worsen with emotional stress. Synovial membrane of the bursa may become damaged or inflamed. This is particularly true in the weight-bearing joints of the spine, hips, knees, and ankles. Obesity increases the stress on joints and can aggravate symptoms.

Osteoarthritis is treated by administering nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), by injecting corticosteroids into the joints, by rest and heat, and by an individualized exercise program. Dietary supplements, including glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and various vitamins, have shown benefits for some individuals and are being studied for safety and effectiveness. Intraarticular injection of hyaluronic acid, a joint lubricant, has received mixed reviews. In severe cases, arthroscopic removal of bone fragments or surgical joint replacements may be necessary.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a collagen disease that results from an autoimmune process. This disease causes inflammation of the synovium, damage to the cartilage and bone of joints, and instability of ligaments and tendons that support the joints. The onset is typically earlier in life, occurring at between 30 and 50 years of age, although a significant number of individuals first develop the disease after age 60. This form of arthritis is seen more commonly in women. Rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by periods of exacerbation (sometimes called flares), during which the symptoms are severe and cause further damage, and remission, during which the progress of the disease halts. Rheumatoid arthritis can also result in muscle atrophy, soft tissue changes, and bone and cartilage changes. Symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis include the following:

• Pain and stiffness, particularly in the morning or after a period of rest

• Warm, tender, painful joints

• Fatigue

The most serious deformities and problems are typically observed when an individual has suffered from this disease for an extended period. Affected individuals are best treated by a rheumatologist, a physician who specializes in the disorder.

Treatments for rheumatoid arthritis include lifestyle changes such as stress reduction, balanced rest and exercise, and joint care using splints to support joints. A wide variety of classifications of medications are used to treat this condition, including the following:

• NSAIDs—such as aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen

• Corticosteroids—such as methylprednisone

• Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—such as etanercept, infliximab

Surgical interventions, including synovectomy, tendon reconstruction, and joint replacement, may be performed to reduce pain, to improve joint function, and to allow the individual to maintain the highest possible level of independent function.

Bursitis

Bursitis, inflammation of the bursa and the surrounding fibrous tissue, can result from excessive stress on a joint or from a localized infection. Bursitis commonly results in joint stiffness and pain in the shoulder, knee, and elbow, ultimately leading to restricted or reduced mobility. Although this problem can occur at any age, age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system make it a more common problem in older individuals. Treatment includes resting the joint and administering NSAIDs. Corticosteroid preparations are occasionally injected into the painful areas to reduce inflammation. Mild range-of-motion exercise is encouraged to prevent permanent reduction or the loss of joint function.

Gouty Arthritis

Gouty arthritis is caused by an inborn error of metabolism that results in elevated levels of uric acid in the body. Crystals of these acids deposit within the joints and other tissues, causing episodes of severe, painful joint swelling. Some joints, such as those of the great toe, are more commonly affected. Chills and fever may accompany a severe attack. Attacks of gout become more frequent as a person ages. If left untreated, this disease can result in the destruction of the joints. It is observed more often in men but is also common in women after menopause. Weight reduction and decreased intake of alcohol and foods rich in purines, such as liver or dried beans or peas, are often recommended.

The respiratory system

The respiratory system provides the body with the oxygen needed for life. Without oxygen, cells quickly die. The brain cells are the most sensitive cells in the body; they will die if deprived of oxygen for as little as 4 minutes. Breathing, the process of inhaling to take in oxygen and exhaling to release carbon dioxide, occurs at a rate of 12 to 20 times per minute for our entire lives. The respiratory system is typically divided into two parts: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The entire respiratory tract is lined with mucous membranes.

Upper Respiratory Tract

On its way to the lungs, air passes through the upper respiratory tract, which includes the air passages of the nose, mouth, and throat, all of which are located above the chest cavity. Mucous membranes line the nasal passages and warm and humidify the air that passes through the nose. Cilia and mucus in the nasal passages trap particulate matter (bacteria and debris) and sweep it toward the pharynx, where it is routinely swallowed and destroyed by gastric acid. The cough and sneeze reflexes also help prevent debris and foreign objects from entering the respiratory tract. The pharynx, which is located at the back of the oral cavity, has three segments: the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and laryngopharynx.

The nasopharynx is connected to the middle ear by the eustachian tubes, which help maintain proper air pressure in the middle ear. The larynx, or voice box, is composed of cartilage rings and folds of tissue, called vocal folds. The epiglottis, which is the uppermost cartilage ring, prevents food from entering the airway. During inhalation, the vocal folds move to the sides of the larynx to allow air to pass freely. During exhalation, we can speak and sing by controlling the distance between these folds, which vibrate when air is forced through them and produce sound.

Lower Respiratory Tract

The lower respiratory tract includes the lower trachea, bronchial passages, and alveoli, all of which lie within the chest cavity. The trachea is a cartilaginous passageway that connects the larynx to the bronchial passages of the lungs. The trachea branches into two major bronchi, which further divide like the branches of a tree into smaller and smaller bronchioles. At the ends of the bronchioles are the alveoli, or air sacs, which are the functional units of respiration. A thin layer of fluid lines each tiny air sac, which is surrounded by pulmonary capillaries to allow the efficient exchange of gases by diffusion. It is here that oxygen enters the bloodstream for transport to body tissue, and it is here that carbon dioxide from the body leaves the bloodstream. This gaseous exchange is essential for normal cell function and for the maintenance of the blood’s acid-base balance.

Because the alveoli have a moist lining, their surfaces could adhere if they touched when the alveoli were empty. This is prevented by a special protein substance called surfactant.

Air Exchange (Respiration)

The movement of air into and out of the alveoli is called ventilation. Ventilation requires the action of muscles, primarily the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and moves downward while the intercostal muscles pull the ribs upward and outward. These combined activities increase the size of the chest cavity until the air pressure inside the lungs is lower than the atmospheric pressure and air is drawn into the lungs. This process is known as inhalation or inspiration. When the air pressure inside the lungs equals or exceeds atmospheric pressure, air ceases to enter the lungs. When the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax, the diaphragm moves upward and the ribs move inward, making the chest cavity smaller. As the chest cavity becomes smaller, the pressure in the lungs becomes greater than the atmospheric pressure. Air is forced out of the lungs until the pressure in the lungs equals the atmospheric pressure. This action is known as exhalation or expiration. Regulation of respiration is both neurologic and chemical. The respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem continuously monitor and control the rate and depth of involuntary respiration. Most breathing is unconscious and involuntary. If we had to think about inhaling and exhaling every breath, we would have little time to do anything else. However, breathing can be conscious and voluntary. When swimming, singing, or engaging in other activities that require breath control, we can temporarily alter our breathing patterns.

Expected Age-Related Changes

With aging, changes are seen throughout the respiratory tract (Table 3-3; Box 3-1). Years of exposure to air pollution, cigarette smoke, and other hazardous chemicals may take their toll on the air passageways and lung tissue. Decrease in elastic recoil of the lungs leads to diminished air exchange. Mucous membranes in the nose become drier as the fluid content of body tissue decreases; thus, the incoming air is not humidified as effectively. The number of cilia decreases, diminishing the ability of the cilia to trap and remove debris. Decreased vocal cord elasticity leads to changes in voice pitch and quality, and the voice develops a more tremulous character.

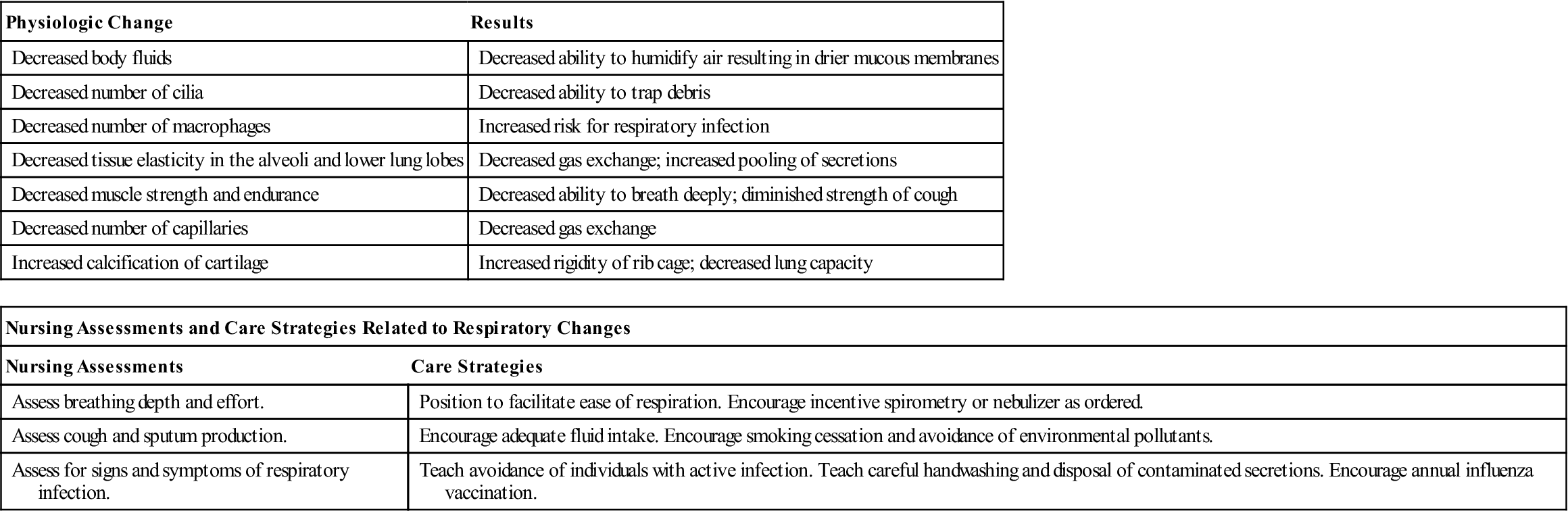

Table 3-3

Respiratory Changes Associated With Aging

| Physiologic Change | Results |

| Decreased body fluids | Decreased ability to humidify air resulting in drier mucous membranes |

| Decreased number of cilia | Decreased ability to trap debris |

| Decreased number of macrophages | Increased risk for respiratory infection |

| Decreased tissue elasticity in the alveoli and lower lung lobes | Decreased gas exchange; increased pooling of secretions |

| Decreased muscle strength and endurance | Decreased ability to breath deeply; diminished strength of cough |

| Decreased number of capillaries | Decreased gas exchange |

| Increased calcification of cartilage | Increased rigidity of rib cage; decreased lung capacity |

| Nursing Assessments and Care Strategies Related to Respiratory Changes | |

| Nursing Assessments | Care Strategies |

| Assess breathing depth and effort. | Position to facilitate ease of respiration. Encourage incentive spirometry or nebulizer as ordered. |

| Assess cough and sputum production. | Encourage adequate fluid intake. Encourage smoking cessation and avoidance of environmental pollutants. |

| Assess for signs and symptoms of respiratory infection. | Teach avoidance of individuals with active infection. Teach careful handwashing and disposal of contaminated secretions. Encourage annual influenza vaccination. |

Musculoskeletal system changes that occur with aging alter the size and shape of the chest cavity. Kyphosis contributes to a barrel-chested appearance. Costal cartilage located at the ends of the ribs calcifies and becomes more rigid, thus reducing the mobility of the rib cage. Intercostal muscles atrophy, and the diaphragm flattens and becomes less elastic. All of these changes reduce lung capacity and interfere with respiratory function, resulting in a decreased ability to inhale and exhale deeply.

Several factors increase the possibility of inadequate oxygenation and the risk for respiratory tract infections in older adults. The cilia movement inside the lungs decreases. The airways and alveoli are less elastic, and there is a decrease in the number of capillaries surrounding the alveoli, which interferes with gas exchange. The lung tissue itself has decreased physical mobility and elasticity, with can lead to increased pooling of secretions, especially in the lower lobes.

Common Disorders Seen with Aging

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is not a single disease but a group of three commonly occurring respiratory disorders: asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. Although they may appear independently, these disorders usually occur in a combination. COPD is common in people who have a history of smoking or who have had a high level of exposure to environmental pollutants. In asthma, the trachea and bronchioles are extremely sensitive to a variety of physical stimuli and emotional stress that then cause constriction of the bronchial passages and increase mucus production within the airways. This narrows the airways and restricts airflow. Elderly individuals may be less aware of bronchospasms and therefore be slower to seek emergency care. This can result in poor outcomes. Emphysema is characterized by changes in the structure of the alveoli. The air sacs lose elasticity, become overinflated, and are ineffective in gas exchange. Chronic bronchitis involves inflammation of the trachea and bronchioles. Chronic irritation leads to excessive mucus secretion and a productive cough.

Individuals with COPD manifest symptoms such as productive cough, wheezing, cyanosis, and dyspnea on exertion. They are at higher risk for developing respiratory tract infections; in severe cases, respiratory failure can occur.

Influenza

Influenza, often referred to as the flu, is a highly contagious respiratory infection caused by a variety of influenza viruses. Many different strains of influenza have been identified, and new forms are being identified continually. The various forms of influenza, such as the Hong Kong or Beijing flu, are often named for the area where they are first recognized. Epidemics occur at regular intervals and are seen most often in the winter months. The virus is usually spread through airborne droplets and moves quickly through groups of people who live or work in close contact with one another. The incubation period is brief, often only 1 to 3 days from the time of exposure. The onset of symptoms is sudden; symptoms include chills, fever, cough, sore throat, and general malaise and may be dramatic and leave the victim feeling severely ill.

Older adults are at higher risk for serious complications of influenza than are younger people. More than 90% of deaths resulting from influenza occur in the older-than-65 population. Influenza presents a special danger for older adults with a history of respiratory disease or other debilitating conditions. Yearly flu shots are recommended for all persons older than 65 years of age to reduce the chance of contracting the most common forms of influenza. Immunizations should be given in the fall so that the level of immunity is high before the risk for exposure occurs. Immunization should be obtained every year because the vaccine is different from the previous year. Each year the vaccine is customized to protect against the particular strain of the virus that is anticipated to be prevalent in the country.

Some people refuse or are hesitant to take the vaccine because of the mild symptoms that may be experienced after inoculation. It is important to explain to older adults that these symptoms are mild and will protect them from more severe problems later. Individuals who are allergic to eggs should not receive the vaccine. Influenza vaccine is cultured in egg protein and can cause a serious allergic reaction in allergic individuals. Given properly, these vaccines are 70% to 80% effective in preventing illness.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is acute inflammation of the lungs caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, chemical, or mechanical agents. In response to the agent, the alveoli and bronchioles become clogged with a thick, fibrous substance that decreases the ability of the lung to exchange gases. Pneumonia can progress to a state in which the exudate fills the lung lobes, which then become consolidated or firm. Pneumonia can be detected by radiologic examination. Breath sounds exhibit character-istic changes.

The symptoms of pneumonia differ with the causative organism. Viral pneumonia, sometimes called walking pneumonia, is most commonly seen following influenza or another viral disease. Symptoms include headache, fever, aching muscles, and cough with mucopurulent sputum. Treatment for viral pneumonia varies according to the symptoms.

Bacterial pneumonia can be caused by a number of organisms, most commonly Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Klebsiella, and Legionella. The symptoms of bacterial pneumonia are abrupt and dramatic in onset. Chills, fever up to 105° F, tachycardia, and tachypnea are common, as is pain with respiration, or dyspnea. The associated cough may be dry and unproductive or purulent and productive. The color of the sputum is significant and should be observed carefully. The type of microorganism involved can be determined by Gram stain and sputum culture. Bacterial pneumonia is treated with bacteria-specific antibiotics and supportive medical and nursing care.

Aspiration pneumonia is an inflammatory process of the bronchi and lungs caused by inhalation of foreign substances such as food or acidic gastric contents. The risk for aspiration is highest in older adults with a poor gag reflex and in those who must remain supine, because these individuals can easily inhale or regurgitate food during oral or tube feeding. Aspiration of highly acidic gastric secretions can lead to cell membrane damage with exudation and, ultimately, to respiratory distress. Aspiration of large amounts of feeding solution is likely to trigger coughing or choking episodes and dyspnea. If these fluids are not removed immediately by suction, respiratory distress and death may result. Aspiration of small amounts of liquid can result in continued and progressive inflammation of the lungs. The person suffering from aspiration pneumonia typically has a rapid pulse and respiratory rate. Sputum is frothy but free of bacteria; however, a superimposed bacterial infection may develop.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which spreads by means of airborne droplets. When an infected person coughs or sneezes, contaminated droplets are released into the air. These droplets are inhaled by other people, the bacillus lodges in their lungs, and the disease spreads. Malnutrition, weakening of the immune system, crowded living conditions, poor sanitation, and the presence of systemic diseases such as diabetes and cancer increase the older adult’s risk for contracting tuberculosis.

The symptoms of tuberculosis include cough, night sweats, fever, dyspnea, chest pain, anorexia, and weight loss. The cough may be nonproductive or productive. Sputum may be green or yellow; with hemoptysis, the presence of blood may impart a rusty color.

Because skin tests for tuberculosis are not reliable in older adults, diagnosis is based on chest radiography or sputum cultures of acid-fast bacilli. Early detection is important to prevent further spread of the disease.

Treatment today consists of drug therapy using a variety of antimicrobial agents such as isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and streptomycin. A combination of these drugs is usually administered and continued for many months. Many of these drugs are associated with numerous adverse effects, particularly in older adults. Nursing care of the older adult with tuberculosis focuses on maintaining good nutrition, monitoring compliance with the medication administration schedule, and detecting side effects.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer, or bronchogenic cancer, is one of the most deadly forms of cancer in the United States. The age range at which diagnosis of lung cancer peaks is 55 to 65 years. Although lung cancer is more common in men, it has become increasingly common in women and has recently passed breast cancer as a leading cause of death. The survival rate after diagnosis of lung cancer is poor, rarely exceeding 5 years.

Lung cancer results from exposure to carcinogenic, or cancer-causing, agents, particularly tobacco smoke, air pollution, asbestos, and other hazardous industrial substances. Cough, chest pain, and blood-tinged sputum are typical symptoms, which can easily be missed because they resemble those of pneumonia and other common respiratory conditions of older adults.

The treatment of choice is surgical resection of the lungs. This procedure is associated with a high mortality rate in older adults. Radiation and chemotherapy are used in some patients, with varying amounts of success.

The cardiovascular system

The cardiovascular system moves blood throughout the body. This continuous, closed system is responsible for the transportation of blood with oxygen and nutrients to all body tissue. It also transports waste products to the organs that remove them from the body. Through its action, the cardiovascular system helps maintain homeostasis within the body. The heart pumps the blood, and the blood vessels dilate or constrict to aid in the maintenance of blood pressure and exchange of materials between the blood and body tissue.

Heart

The heart is a muscular organ located centrally in the thoracic cavity between the lungs. The sternum, or breastbone, protects its anterior surface. The heart’s tip, or apex, projects toward the left side of the body and extends directly above the diaphragm muscle.

Three pericardial membranes form a sac around the heart. The innermost membrane is on the surface of the heart and is called the epicardium, or visceral pericardium. The middle membrane is the parietal pericardium, and the outermost membrane is the fibrous pericardium. The space between the epicardium and the parietal pericardium is the pericardial cavity; it contains a small amount of serous fluid that prevents the membrane surfaces from rubbing together during cardiac activity.

The heart, which is composed of cardiac muscle (called myocardium), is a hollow organ with four distinct chambers. The right side of the heart consists of the right atrium and right ventricle, which are separated by the tricuspid valve. The right side of the heart is a low-pressure pump that moves deoxygenated blood through the pulmonary valve and pulmonary artery and out to the lungs. After the blood is oxygenated, it returns to the left side of the heart through the pulmonary vein. Because less effort is required to move blood the short distance through the lungs of a healthy individual, the muscle wall of the right side of the heart is relatively thin. The left side of the heart also has two chambers, the left atrium and left ventricle, which are separated by the mitral valve. The pressure within the left side of the heart is higher than that in the right side because the left side is responsible for blood distribution to the entire body. To provide the necessary force, the left ventricle has a thicker muscle wall than does the right ventricle. When blood leaves the left ventricle, it proceeds through the aortic valve into the aorta and its branches and out to the rest of the body.

The heart chambers and valves are lined with endocardial tissue. Endothelial tissue continues out from the heart and lines all of the blood vessels. This smooth layer allows the blood to flow freely and reduces the risk for clot formation.

Blood Vessels

The arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. With the exception of the pulmonary artery, arteries carry oxygenated blood. The aorta, the largest artery in the body, leaves the heart and branches into a series of progressively smaller arteries and capillaries. These vessels run through the entire body and reach all organs and tissues.

Arterial walls are composed of three layers of tissue. The innermost layer is the endothelium, or tunica intima. This layer is a continuation of the endocardial tissue that lines the inside of the heart. The middle layer, or tunica media, is composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue. This smooth muscle is controlled by the autonomic nervous system and dilates or constricts the artery to maintain the blood pressure. The outermost layer, or tunica externa, is composed of strong fibrous tissue that protects the vessels from bursting or rupturing under high pressure. The relative thickness of the tunica media and externa enables the arteries to perform properly.

The veins are vessels that carry blood toward the heart. With the exception of the pulmonary vein, veins carry deoxygenated blood. Venules, the smallest veins, are connected to the smallest capillaries. Veins and venules are composed of the same three layers of tissue seen in arteries. The veins use a system of valves, which are created by endothelial tissue folds, to aid in the return of blood to the heart. The valves prevent backflow of blood, which could be a problem when the blood is moving toward the heart against the force of gravity.

The smooth muscle layer of the veins is much thinner than that of the arteries because the veins are not as important in the regulation of blood pressure. The outer fibrous layer is also thinner because blood pressure in the veins is much lower than that in the arteries.

A special set of blood vessels, the coronary arteries and veins, supplies the heart with blood enriched with oxygen and nutrients. These arteries are the first branches of the ascending aorta. Because the heart muscle works continuously, it has high oxygen demands. Any condition that obstructs the normal supply of blood to the heart can damage the myocardium. If it is severely deprived of oxygen and nutrients, the heart muscle will die. Too much damaged or destroyed tissue results in cardiovascular system failure and death.

Conduction System

To function effectively, the cardiovascular system must work in a controlled, organized, and rhythmic manner. The heart’s rhythm is established by specialized cells within the heart muscle that make up the electrical system of the heart. The body’s natural pacemaker, the sinoatrial node, is a group of specialized cells in the right atrium. Impulses generated in the sinoatrial node travel across the atria to the atrioventricular node in the lower interatrial septum. From there they are conducted through the bundle of His, through the right and left bundle branches, through the Purkinje fibers, and, finally, to the ventricular myocardium. When the cells of the heart’s electrical system depolarize, the myocardium depolarizes and the heart contracts (systole), following which the special cells and the myocardium repolarize as the heart relaxes (diastole). This process alternately empties and fills the chambers, which pump blood through the circulatory system.

Expected Age-Related Changes

The heart does not atrophy with aging as other muscles do. In fact, the heart muscle mass increases slightly with age, and the thickness of the wall of the left ventricle also increases slightly. The increase in muscle mass may occur to offset some loss of tone. The aging heart may function less effectively even when no pathologic changes are present (Table 3-4). Loss of tone typically leads to the decrease in maximal cardiac output seen in older adults. The normal conduction system, SA node, AV node, the bundle of His, and its branches all lose cells starting fairly early in life (in the twenties). Cardiac response to autonomic stimulation shows decreased response to adrenergic stimulation due to changes in the receptors. Older persons enhance cardiac output by increasing stroke volume, whereas younger persons increase output by increasing heart rate.

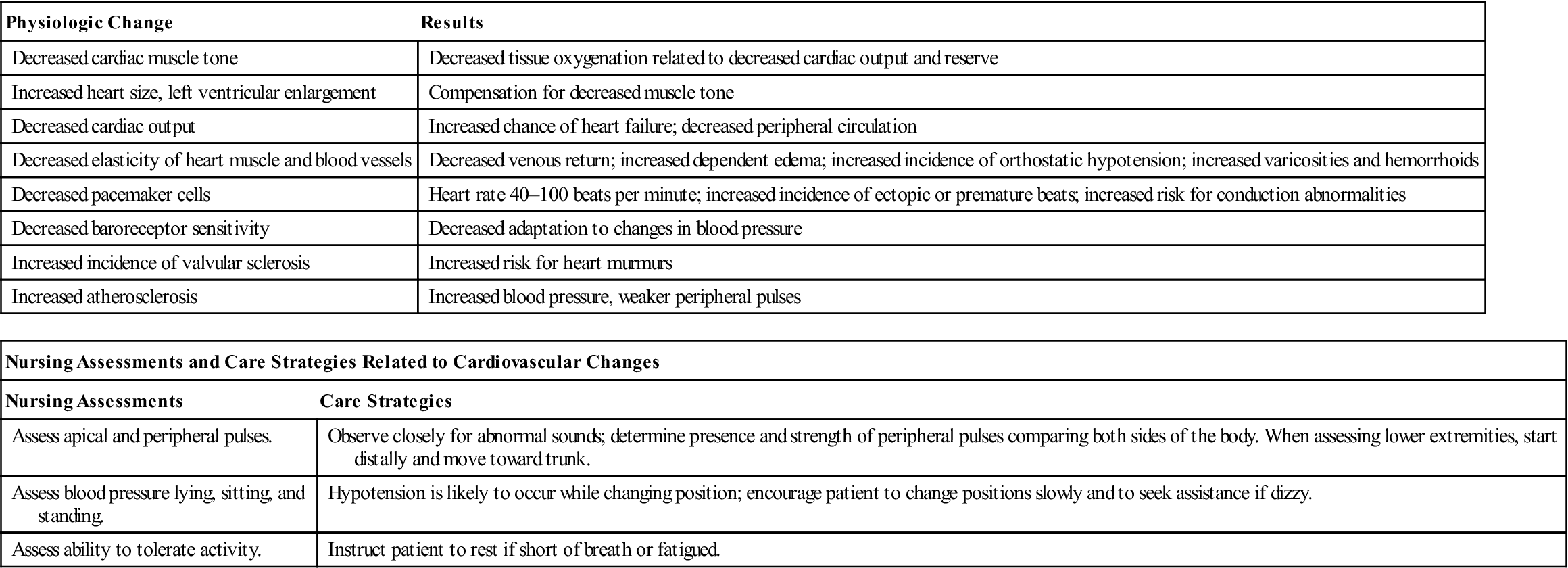

Table 3-4

Cardiovascular Changes Associated With Aging

| Physiologic Change | Results |

| Decreased cardiac muscle tone | Decreased tissue oxygenation related to decreased cardiac output and reserve |

| Increased heart size, left ventricular enlargement | Compensation for decreased muscle tone |

| Decreased cardiac output | Increased chance of heart failure; decreased peripheral circulation |

| Decreased elasticity of heart muscle and blood vessels | Decreased venous return; increased dependent edema; increased incidence of orthostatic hypotension; increased varicosities and hemorrhoids |

| Decreased pacemaker cells | Heart rate 40–100 beats per minute; increased incidence of ectopic or premature beats; increased risk for conduction abnormalities |

| Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity | Decreased adaptation to changes in blood pressure |

| Increased incidence of valvular sclerosis | Increased risk for heart murmurs |

| Increased atherosclerosis | Increased blood pressure, weaker peripheral pulses |

| Nursing Assessments and Care Strategies Related to Cardiovascular Changes | |

| Nursing Assessments | Care Strategies |

| Assess apical and peripheral pulses. | Observe closely for abnormal sounds; determine presence and strength of peripheral pulses comparing both sides of the body. When assessing lower extremities, start distally and move toward trunk. |

| Assess blood pressure lying, sitting, and standing. | Hypotension is likely to occur while changing position; encourage patient to change positions slowly and to seek assistance if dizzy. |

| Assess ability to tolerate activity. | Instruct patient to rest if short of breath or fatigued. |

The heart valves show some degree of thickening and increased calcification with aging, resulting in mild degrees of mitral valve regurgitation. As in other body tissues, the endocardium and endothelium lose elasticity with aging. When these tissues become increasingly fibrous and sclerotic, venous return from the peripheral areas of the body decreases. Orthostatic hypotension occurs because the circulation does not respond quickly to postural changes. Less effective pumping of the heart muscle combined with sclerotic changes in the veins can lead to dependent edema and to the appearance of varicosities in the lower extremities. Weakness of the valves in the rectal veins can lead to hemorrhoids.

Common Disorders Seen with Aging

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, accounting for more than 75% of all deaths in men and women older than 65 years of age.

Coronary Artery Disease

Some degree of coronary artery disease is present in most persons older than age 70. The coronary arteries supply blood to the heart. If these vessels become narrowed or obstructed because of atherosclerosis, the heart may not receive adequate oxygen and nutrients. Many older adults have seriously obstructed coronary arteries, yet they remain essentially asymptomatic. Once circulation to the heart muscle decreases significantly, the amount of oxygen delivered to the heart decreases and ischemia occurs. The pain that may be experienced with ischemia is referred to as angina pectoris (literally, chest pain). Although the symptoms of ischemia do include chest pain or pain radiating down the left arm, such pain is not always present or recognized in older adults. Vague gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort or shortness of breath may be reported, or there may be no symptoms at all. People experiencing an angina attack are advised to decrease their activity and rest until the episode passes. Physicians usually prescribe coronary vasodilators, such as nitroglycerin, or β-adrenergic blocking agents for people with ischemic heart disease.

When one or more coronary arteries become totally obstructed by atherosclerosis or embolus, the person is said to have a myocardial infarction (MI), or heart attack. The mortality rate from MI is four times higher in those older than 70 years of age than in younger individuals. Symptoms of a heart attack in older adults are more variable than in younger people. Most older adults are likely to have symptoms such as sudden-onset dyspnea or chest discomfort, confusion, syncope, and decreased urine production. Diaphoresis is uncommon. Many older adults who have heart attacks die suddenly (Box 3-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree