Chapter 9 Physical assessment

The physical assessment follows the holistic intake. The information gathered during the intake provides the subjective view of the patterns of disharmony. The physical assessment provides an objective look at how the patterns have affected the physical health of the patient. Symptoms and diseases are multifactorial, yet they manifest in ways that have a logical pattern and that convey meaning as to the causative factors. The aim of the physical assessment is to correlate the patterns that emerged during the holistic intake with the physical signs and symptoms, to identify the causative factors, and to determine the treatment strategy that is required to restore health.

There are countless ways of perceiving what is going on with the person who is in front of you and who needs your help and that there are many ways of stimulating healing response (Oshman 2003).

The body provides many windows for reading the symptom patterns and the more windows that a practitioner looks through, the greater the confirmation of the pattern. The windows, or areas of assessment, provide a range of options for each practitioner, based on their unique skill set and areas of interest. The more that a practitioner studies and practices a specific area of assessment, the greater the depth of information they discover. For example, a practitioner who has mastered tongue and pulse diagnosis will be able to assess the subtleties of a patient’s disharmony through that one window. A practitioner does not have to be master of all the aspects of assessment. What is helpful is for a practitioner to discover where their strengths lie and to develop them, without losing sight of the value of the other windows. I encourage practitioners, especially young practitioners, to initially assessall areas of the body in order to discover the various ways that human beings have of expressing disharmony.

PHYSICAL STRUCTURE

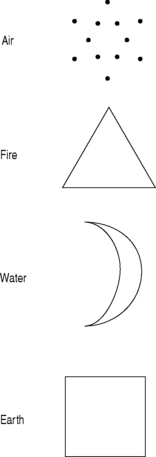

The physical structure and appearance of a patient is often the first thing that a practitioner observes. This observation provides the practitioner with an indication of the personality and temperament of the patient. The unique qualities that are observed and attributes that they represent can be understood based on the elemental properties discussed in Chapter 5. Figure 9.1 looks at how the elements appear in shape and form in the body.

Observation

Hippocrates introduced the art of clinical observation as the necessary basis for pathologic diagnosis (Hahnemann 1997). Everything that a practitioner observes holds a meaning. Most of what we observe, in every aspect of our life, is interpreted without our conscious input and awareness of the interpretation process. The mind identifies objects by extracting diagnostic visual cues and matching this information to a prototypical, structural description stored in memory (Biederman 1987, Bar et al 2001) In order to assess the symptom patterns, it is essential to learn and ‘program’ energetic pattern correlations for observed (and auditory) clues into the unconscious mental templates that the mind uses for assessment.

Observation involves having ‘soft eyes’ and ‘open ears’. It recognizes the subtleties as well as the details; the harmony and disharmony that a patient displays. It is about being present in the process, slowing it down, and paying attention. For every aspect of the assessment ask yourself what stands out, what is missing, what seems out of place, and what’s different. Before you look for the details, look and listen for the overall pattern that a patient is displaying, such as an overriding sign of excess or deficiency. Most qualities can be caused by a number of different factors; below is an example of the most common causes of the following symptoms:

Palpation

Palpation assessment progresses through successive degrees of attenuation from bone to muscles, to fascia, to fluid, to energy fields (Chaitow 1997). The structure of the body governs its function, and function dictates structure and the movement and freedom of motion of every tissue, organ, and cell is needed for efficient working of the body. Palpation determines the degree to which each part of the body is able to move freely and it is used to confirm and expand on any information that is observed.

Every cell, tissue, organ, and structure of the body is linked as a complex dynamic network. There is an intrinsic nature and organizational matrix within the human body, a connection between the skin, muscles, joints, organs, as well as the emotional state of the patient; each one affects theothers. There is a flow of fluids and energy throughout the body that nurtures and supports each component. An alternation in any aspect alters the whole.

The objectives of palpation are to: (Chaitow 1997)

Although palpation is commonly thought of as a means of accumulating evidence to be used when coming towards an assessment, diagnostic or prognostic position, there exist situations in many areas of manual palpation where there is only a theoretical division between palpation/assessment and therapeutic activity (Chaitow 1997).

Posture

A patient’s posture reveals their sense of inner and outer support, their flexibility, and their openness to external factors. The way a person moves and stands indicates inner characteristics (Mattsson & Mattsson 2002). An aligned posture allows for movement through the full length of the body.

Assessing posture is very important especially when pain and discomfort with movement is a concern, or when you observe structural changes. Posture is the result of the over use, misuse, or abuse of underlying structures of the body, and their respective alignment and positioning both right to left and front to back over time. It is affected by the size and strength of the bones –an earth quality; the fluid within the joint spaces – a water quality; the muscles that attach to the bone – a fire quality; the ease and freedom of movement – an air quality; and the desire to take up space – an ether quality.

When assessing posture, look at the body from the front, the back, and the sides, both when a patient is standing and when they are lying down (Fig. 9.2). It is easiest to see the key features of posture when a patient is wearing as few clothes as is reasonable. A gravity board, plumb line, and grid wall are the easiest ways to properly identify and measure the differences in the posture alignment. Initially assess your patient in as relaxed and natural state as possible. You are looking for how they normally stand and how their weight is distributed. Next have them stand with their heels exactly in line and square to a real or imaginary plumb line running down the center of the body from the head to the feet. The following are the main patterns that are displayed in a postural assessment:

The alignment of posture front to back is also indicative of underlying functional changes in the body. For example,

If the head is pulled back, the movement of the neck is restricted and the chest is more fixed and immobile, which means restrictions in exploration and perception of the surroundings. Carriage coincides with a stiff way of viewing the world – rules are followed categorically, fantasy is an obstacle and rigid working-style is favoured (Mattsson & Mattsson 2002).

GAIT ASSESSMENT

The arms follow the trunk, giving equilibrium and emphasizing pace. The gaze is directed straight ahead, the head and neck move freely in the vertical line, the eyes and ears readily incorporating necessary information. This way of walking is open and grounded; there are few restrictions (Mattsson & Mattsson 2002).

ASSESSMENT OF JOINTS

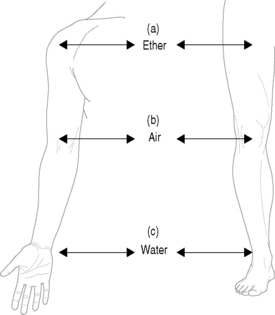

It is common for patients to have pain or discomfort around joints, as joints are responsible for movement of the structural body. Overall joints represent the qualities of space – ether – that is the freedom to move through life. As ether is the element from which all other elements are derived, the movement of the joints and the location of joint symptoms bring in all the other elements. The joints located in the core of the body, the spine, relate to the freedom of movement that a patient feels with respect to themselves, and their ability to be themselves. The movement of the peripheral joints relates more to the interaction between a patient and their external surroundings. The joints on the upper body also have a corresponding joint on the lower body; for example the elbows and the knees are both air joints, the wrists and ankles are both water joints. The joints on the top of the body refer more to acute or current situations, the joints on the lower aspect of the body often relate more to chronic situations or patterns.

Each joint has a corresponding symbolic meaning, for example the shoulders symbolize giving and receiving, hips symbolize moving forward. The elbow and knee correlate with the qualities and characteristics of air element; the wrist and ankle correlate with the water element (see Fig. 9.3).

BREATHING

The function of breathing is said to represent a bridge between the conscious and unconscious – breathing can be controlled by our will, but mostly we breathe reflexively (Mattsson & Mattsson 2002).

When patients are dealing with stress, of any type, the initial response of the body, often unconscious, is for the breath to become rapid and shallow. For example, the term ‘anxiety’ has its linguistic root in the Latin word angustio, which corresponds to suffocation. Likewise, when a person feels anxious it will feel as if breathing is obstructed (Mattsson & Mattsson 2002).

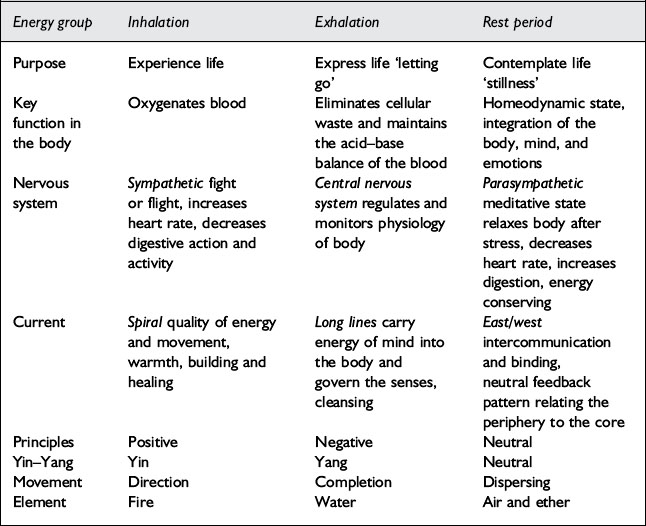

The qualities of breathing can be broken down into inhalation, exhalation, and the rest period as described in Table 9.1.

Breathing overall is an air element, yet the influences, excess and deficiency of all the elements affect breath. What you are assessing with breathing is thefreedom of the air element to move among and within the other elements. The following is how the energetic patterns manifest in breath.

Steps to assessing breathing patterns

Assessing breathing patterns involves conventional methods, such as auscultation and radiographs to rule in and rule out specific diseases, such as asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, and lung pathologies. There are many factors that can disrupt normal breathing patterns and assessing the qualitiesof how a patient breathes provides another layer of information that is helpful in determining the causative factors and in deciding on the treatment strategy that is the most appropriate. For example, a sigh is a deep and shallow breath. It is a symptom of fatigue, depression, or grief. The word ‘to sigh’ means ‘to lament, mourn over’. Yawning is a sign of drowsiness, dullness, or boredom. It has the quality of earth. Anxiety, on the other hand, causes rapid, shallow breaths. It is often associated with fire or air imbalances.

The following is a guide for assessing the patterns of breathing:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree