Chapter 6. Pharmacological methods of pain relief

Introduction

Although women no longer need to experience the pain associated with childbirth, the decision regarding whether or not to use pharmacological methods of analgesia is not straightforward. Women vary in their hopes and fears regarding the childbirth experience. Some want to cope with as little pain relief as possible and others want a pain-free birth. The increasing use of technology throughout maternity care, including induction, acceleration and electronic monitoring of labour, has increased the need for effective means of alleviating the associated pain.

Despite the wide availability of epidural services, however, an increasing proportion of women are very worried about the thought of pain in labour. A prospective study exploring women’s expectations and experiences of intrapartum care in 2000 and comparing them with data from women in 1987 found that 26% of primigravidae in 2000 reported feeling ‘very worried’ about the thought of pain in labour compared with 9% in 1987 (Green et al 2003).

Much emphasis is placed in current maternity provision on the maxim that women should be fully informed and involved in decisions about their care (Department of Health (2007a) and Department of Health (2007b), Maternity Care Working Party 2007, NICE 2007). Although ideally women should receive information and consider the options before they are distracted by painful uterine contractions, they will inevitably face decisions about their care during labour. To participate actively, the woman needs to remain awake and fully aware of what is happening around her but at the same time, she needs to be able to cope with her pain. Thus, finding analgesia that does not oversedate but is relatively effective is a particular challenge for the woman who requests pharmacological means of pain relief.

Inhalational analgesia

When pain relief is achieved by breathing in an anaesthetic gas, this is referred to as inhalational analgesia. The fact that the overall concentration of the gas is much less than would be administered if an anaesthetic were required means that the woman remains conscious. However, the fact that it is an anaesthetic agent should alert the midwife to the importance of maintaining careful observation of the woman’s wellbeing.

Nitrous oxide is the only form of inhalational analgesia available in the UK. It is provided for women in labour as a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen and is commonly known as Entonox. It is valuable as it can be used while other forms of analgesia are being prepared or taking effect.

Method of administration

Self-administration prevents overdose and anaesthesia being induced. For this reason it is important that the midwife informs the birth partner not to help the woman by holding the mask over her face.

Some coordination is required to achieve optimum benefit from Entonox. As it takes 20–60 seconds to take effect, the woman needs to start using it as soon as a contraction begins, rather than when it has reached its peak. The student midwife can help by placing a hand on the fundus and detecting the contraction before it becomes painful to the woman. Thus the student can inform the woman when to start using the Entonox and to stop when the peak of the contraction has been overcome.

It must be explained to the woman that the gas is not being released constantly from the mask but that it requires the woman to take sufficiently deep breaths in order to open the valve. The woman needs to press the mask firmly over her nose and mouth to form a tight seal. She should then be encouraged to take deep, slow breaths, keeping the mask on her face for both inspiration and expiration. The Entonox apparatus makes a characteristically deeper noise when the valve opens, following the correct breathing technique.

It is important that the woman removes the mask from her face in between contractions to enable her to breathe some fresh air and regain her awareness. Entonox is quickly excreted via the lungs and she should feel her usual self within about 2 minutes.

Some women do not like the thought of breathing into a mask. They may associate the sensation with going to the dentist and might prefer to use a mouthpiece. The woman will require frequent sips of water; this method causes the mouth to feel very dry as water is lost in expired air.

Impact on the woman

The longstanding and continued use of Entonox in labour reflects its relative safety as a pharmacological method of analgesia. However, inappropriate use of Entonox can lead to hyperventilation and associated hypoxia, dizziness and tetany (Jordan 2002). Therefore, a woman using Entonox must have her respiration rate closely observed and complaints of tingling or spasm in her hands or feet should lead to suspension of its use. In a study comparing the effects of Entonox and epidural analgesia on arterial oxygen saturation in labour (Arfeen et al 1994) it was reported that women who used Entonox had longer and more severe hypoxic episodes than women who had an epidural.

In addition, women using Entonox may suddenly feel nauseous and light-headed (NICE 2007). The midwife supporting her must be prepared for this (vomit bowl and tissues to hand) and ensure that she is positioned to avoid aspiration. A cool facecloth placed on the back of the woman’s neck or forehead may alleviate such symptoms in between use.

Prolonged occupational exposure to Entonox has been associated with spontaneous abortion and congenital abnormality (BOC 1999).

Opioid analgesia

What are opioids?

An opioid drug is one that attaches itself to the body’s opioid receptors – that is, those that respond to endorphins and enkephalins (Jordan 2002). Opioids used in midwifery practice include pethidine, diamorphine and meptazinol. They are ‘controlled drugs’ which means that their use is closely monitored under legislation by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and they fall into Class A. These classes are used to enable penalties to be attributed to their abuse. Controlled drugs are further categorized according to the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001, which provides guidance on how they should be stored and administered: opioids fall under Schedule 2. The Health Act (2006) introduced comprehensive governance arrangements for the monitoring and inspection of controlled drugs. It also introduced standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the use and management of controlled drugs and the requirement that all healthcare organizations should have an Accountable Officer to oversee these arrangements. In addition to the legislation on the administration of controlled drugs and professional guidance (NMC 2007), individual NHS trusts have their own frameworks for safe practice (Department of Health 2007c). NICE (2007) recommend that opioids should be available for women to use in all birth settings.

Route of administration

Opioids are usually given by intramuscular injection during labour. It is common practice for intramuscular injection to be administered into the muscle in the buttock or thigh (see Baston et al 2009 for injection technique). However, Heelbeck (1999) reports a faster effect when the drug is given into the deltoid muscle of the arm (using a smaller needle), with therapeutic effect being achieved in 5 to 10 minutes rather than 20 minutes. Pethidine causes local irritation and repeated administration can lead to fibrosis of the muscle. The same site should not be used more than once during labour (Jordan 2002).

Effect on the woman

Heelbeck (1999) raises the issue that women who have been over-sedated in labour are unable to voice their wishes effectively. This can result in them agreeing to interventions or practices that they had previously felt quite strongly against. They may sleep for long periods and feel that they missed out on their labour experience. There is a fine balance between achieving analgesic effect and inducing drowsiness.

A lack of analgesic effect of both pethidine and other opioids administered to women in labour has been highlighted (Briker & Lavender 2002). Indeed, in one study (Olofsson et al 1996a) the authors concluded that it was unethical to meet women’s requests for analgesia by sedating them. Another problem with pethidine use is the fact that professionals judge its effectiveness to be greater than the women who use it (Findley & Chamberlain 1999).

Although there are a range of hospital protocols for the administration of opioids during labour, in practice it often becomes common practice to use a standard dose, for example, 100mg intramuscularly 3 to 4 hours apart. However, it may be more appropriate to use a smaller dose more frequently, depending on the needs of the individual woman. Larger doses of opioids are also associated with more nausea and vomiting (Maduska & Hajghassemali 1978). This can be prevented by administration of an anti-emetic, such as prochlorperazine (Stemetil) at the same time.

Respiratory depression is a side-effect of all opioids. Pethidine reduces the sensitivity of the respiratory centre to carbon dioxide. The rate and depth of breathing decreases and hypoxia may develop (Jordan 2002). It is essential to monitor a woman’s respiratory rate closely following administration of pethidine, especially if she falls asleep.

The use of morphine in labour is less prevalent than the use of pethidine and is often restricted to women whose babies are known to have died in utero. It has a pronounced sedative effect but weak analgesic impact, although one study (Olofsson et al 1996b) did find a significant reduction in the experience of back pain with intravenous morphine.

Think about why opioids are not given orally during labour.

Find out the protocol for administration of pethidine to a labouring woman in the unit where you work.

Find out the usual dose for intramuscular prochlorperazine.

Revise the physiological control of respiration and the factors that impact on respiration rate.

Effect on the baby

Respiratory depression is also a problem for the neonate as pethidine passes across the placenta. The severity of respiratory depression varies depending on the dose to delivery interval as well as the total dose received. Elimination of pethidine is prolonged in the neonate as this process takes place in the liver, which is immature. The administration of opioids also leads to maternal bradycardia, which results in a drop in blood pressure. Placental perfusion may then be compromised, and a fetal bradycardia and loss of baseline variability of the fetal heart is often observed.

The opioid antagonist naloxone (Narcan neonatal) should always be nearby following administration of pethidine to a woman in labour. If the respiration rate of the neonate is depressed at birth, naloxone should be administered by the midwife immediately and further senior assistance called.

The neonate should be closely observed. S/he may require a repeat dose, as the half-life of naloxone is shorter than that of pethidine.

Find out the correct dose and route of administration of naloxone to a neonate with opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Identify which babies are particularly at risk of respiratory depression.

Find out about the policy where you work for caring for the neonate of a drug-dependent mother.

Breastfeeding

There is some evidence to suggest that administration of pethidine to a woman during labour is associated with an adverse effect on the future breastfeeding behaviour of the neonate (Rajan 1994, Nissen et al 1995, Ransjo-Arvidson et al 2001). In a study examining the effect of birth room practices on breastfeeding success (Righard & Alade 1990) it was reported that, of the neonates whose mothers had received pethidine during labour, 62% did not suck at all in the 2 hours following the birth.

Home birth

When a woman is anticipating a home birth she will discuss her analgesic requirements with the community midwife. In areas where the incidence of home birth is low, community midwives do not always carry a supply of pethidine. If the woman requests pethidine, it can be supplied, via a prescription, from her general practitioner. As such, the pethidine is dispensed to the woman by a pharmacist and becomes her property.

Some GPs are reluctant to prescribe narcotics to pregnant women, being concerned that they will be responsible for its administration and effects. However, midwives can also obtain pethidine via a supply order from a supervisor of midwives (Department of Health 2007c) and dispensed by the hospital pharmacy. In the event that the pethidine is not used during the labour, the midwife must not destroy the drugs, as they remain the woman’s property. She can advise the woman to destroy them in her presence or to return them to the pharmacist from which they were dispensed. The advice that is given and any subsequent action must be documented in the woman’s records.

Epidural

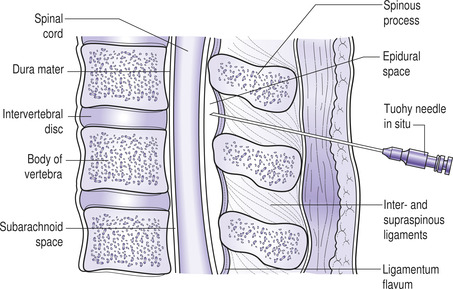

An epidural in labour is a form of analgesia that involves the injection of a local anaesthetic into the epidural space. Larger doses can be given for instrumental or operative births. It involves the insertion of a small plastic catheter into the epidural space, through which drugs can be administered. In order to insert the plastic catheter, a Tuohy needle must first be carefully inserted through the skin and interspinous ligament by an anaesthetist (Fig. 6.1). The plastic catheter is then fed through the needle and the needle is then withdrawn, leaving the catheter in place. Once the epidural is in place, drugs can either be administered intermittently by a midwife, by continuous infusion or controlled by the woman (PCA). The provision of epidural services varies from unit to unit, and although many will provide a 24-hour service for labouring women, this is not a universal standard. In a large prospective study of women’s expectations and experiences of childbirth (Green et al 2003) it was reported that women are increasingly wanting a pain-free labour: from 6% of primiparous women in 1987 to 21% in 2000. Women are also more likely to accept obstetric intervention generally (Green & Baston 2007).

|

| Fig. 6.1 Sagittal section of the lumbar spine with Tuohy needle in the epidural space. (From Johnson & Taylor 2006, with permission.) |

Effect on the woman

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree