Perioperative Nursing

OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT

Introduction

Perioperative nursing is a term used to describe the nursing care provided during the total surgical experience of the patient: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative.

Preoperative phase—from the time the decision is made for surgical intervention to the transfer of the patient to the operating room.

Intraoperative phase—from the time the patient is received in the operating room until admitted to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

Postoperative phase—from the time of admission to the PACU to the follow-up evaluation.

An anesthesia care provider is a professional who can administer and monitor anesthesia during a surgical procedure; he or she may be a licensed physician board certified in anesthesia (anesthesiologist) or a certified registered nurse anesthetist.

Perioperative Safety

The safety and welfare of patients during surgical intervention is a primary concern. Patients entering the perioperative settings are at risk for infection, impaired skin integrity, altered body temperature, fluid volume deficit, and injury related to positioning and chemical, electrical, and physical hazards.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseThe Joint Commission. (2012). Hospital: 2013 National Patient Safety Goals. Available: www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx.

The Joint Commission. (2012). Surgical Care Improvement Project. Available at: www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/.

Surgical Care Improvement Project

The Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP), a national quality partnership interested in improving surgical care by significantly reducing surgical complications, is a coalition of health care organizations that has developed evidence-based interventions that have proven effective.

The goal is to reduce surgical complications by 25%.

Implementing nursing interventions at the earliest stage possible of a developing complication is also of utmost importance.

SCIP measures that have been shown to be effective include:

Prophylactic antibiotic received within 1 hour prior to surgical incision.

Prophylactic antibiotic discontinued within 24 hours after surgery end time.

Cardiac surgery patients with controlled 6:00 a.m. postoperative serum glucose.

Surgery patients with appropriate hair removal.

Urinary catheter removed on postoperative day 1 or postoperative day 2 with day of surgery being day zero.

Patients continue beta-blockers on day of surgery.

Appropriate venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment.

National Patient Safety Goals

National Patient Safety Goals (2013) include:

Prevent infection—use hand cleaning guidelines from the Center for Disease Control or the World Health Organization.

Use proven guidelines to prevent infections that are difficult to treat.

Use proven guidelines to prevent infection of the blood from central lines.

Use proven guidelines to prevent infection after surgery.

Use proven guidelines to prevent infections of the urinary tract caused by catheters.

Prevent mistakes in surgery—make sure the correct surgery is done on the correct patient at the correct place on the patient’s body.

Mark the correct place on the patient’s body where the surgery is to be done.

Pause before surgery to make sure a mistake is not being made.

Types of Surgery

Elective—The scheduled time for surgery is at the convenience of the patient; failure to have surgery is not catastrophic (eg, a superficial cyst).

Required—The condition requires surgery within a few weeks (eg, eye cataract).

Urgent—Necessitates surgery as soon as possible but may be delayed for a short amount of time (eg, internal fixation of fracture).

Emergency—The situation requires immediate surgical attention without delay (eg, intestinal obstruction). This must be done to save life or limb or functional capacity.

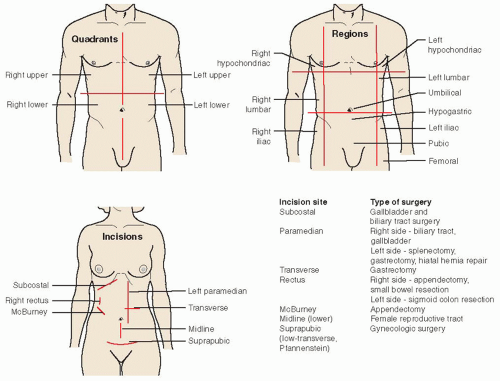

Common abdominal incisions are pictured in Figure 7-1.

Ambulatory Surgery

Ambulatory surgery (same-day surgery, outpatient surgery) is a common occurrence for certain types of procedures. The office

nurse is in a key position to assess patient status; plan the perioperative experience; and monitor, instruct, and evaluate the patient.

nurse is in a key position to assess patient status; plan the perioperative experience; and monitor, instruct, and evaluate the patient.

Advantages

Reduced cost to the facility and insuring and governmental agencies.

Reduced psychological stress to the patient.

Less incidence of hospital-acquired infection.

Less time lost from work by the patient; minimal disruption of the patient’s activities and family life.

Disadvantages

Less time to assess the patient and perform preoperative teaching.

Less time to establish rapport between the patient and health care personnel.

Less opportunity to assess for late postoperative complications. (This responsibility is primarily with the patient, although telephone and home care follow-up is possible.)

Patient Selection

Criteria for selection include:

Surgery of short duration (varies by procedure and facility).

Noninfected conditions.

Type of operation in which postoperative complications are predictably low.

Age usually not a factor, although too risky in a premature neonate.

Examples of commonly performed procedures:

Ear-nose-throat (tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy)

Gynecology (diagnostic laparoscopy, tubal ligation, dilation and curettage).

Orthopedics (arthroscopy, fracture or tendon repair).

Oral surgery (wisdom teeth extraction, dental restorations).

Urology (circumcision, cystoscopy, vasectomy).

Ophthalmology (cataract).

Plastic surgery (mammary implants, reduction mammoplasty, liposuction, blepharoplasty, face lift).

General surgery (laparoscopic hernia repair, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, biopsy, cyst removal).

Ambulatory Surgery Settings

Ambulatory surgery is performed in a variety of settings. A high percentage of outpatient surgery occurs in traditional hospital operating rooms in hospital-integrated facilities. Other ambulatory surgery settings may be hospital-affiliated or independently owned and operated. Some types of outpatient surgeries can be performed safely in the health care provider’s office.

Nursing Management

Initial Assessment

Develop a nursing history for the outpatient; this may be initiated in the health care provider’s office. The history should include the patient’s physical and psychological status. You will also inquire about allergies, tobacco, alcohol, and drug use; disabilities or limitations; current medications (including over-the-counter and herbs); current health conditions (focus should be on cardiovascular and respiratory problems, diabetes, and renal impairments); and any past surgeries and/or problems with anesthesia.

Ensure availability of a signed and witnessed informed consent that includes correct surgical procedure and site.

Explain any additional laboratory studies needed and state why.

Begin the health education regimen. Instructions to the patient:

Notify the health care provider and surgical unit immediately if you get a cold, have a fever, or have any illness before the date of surgery.

Arrive at the specified time.

Restrict food and fluid before surgery according to facility protocol to prevent aspiration of gastric contents. Based on scientific evidence, the American Society of Anesthesiologists has issued guidelines for elective procedures recommending the following:

Clear liquids—minimum fasting of 2 hours.

Breast milk—minimum fasting of 4 hours.

Infant formula—minimum fasting of 6 hours.

Nonhuman milk—minimum fasting of 6 hours.

Light meal—minimum fasting of 6 hours.

Do not wear makeup or nail polish.

Wear comfortable, loose clothing and low-heeled shoes.

Leave valuables or jewelry at home.

Brush your teeth in morning and rinse, but do not swallow any liquid.

Shower the night before or day of the surgery.

Follow the health care provider’s instructions for taking medications, including over-the-counter medications and supplements.

Have a responsible adult accompany you and drive you home; have someone stay with you for 24 hours after the surgery.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAmerican Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. (2011). Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. An updated report. Anesthesiology, 114(3), 495-511.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTMinimum fasting times must be followed to reduce the risk of aspiration, but patients are often instructed to fast after midnight because schedule changes the morning of surgery are possible due to cancellations, which can cause surgery time to be moved forward. Be aware that prolonged fasting before surgery may result in undue thirst, hunger, irritability, headache, and possibly dehydration, hypovolemia, and hypoglycemia.

Preoperative Preparation

Conduct a nursing assessment, focusing on cardiovascular and respiratory status. Determine if patient is diabetic and,

if so, follow glucose control measures. Obtain baseline vital signs, including an oxygen saturation level and current pain score.

Review the patient’s chart for witnessed and informed consent, laterality (right or left, if applicable), lab work, and history and physical.

Verify correct patient, correct site, and correct procedure. Consider “time-out” and SCIP measures, including marking of incision.

Make sure the patient has followed food and fluid restrictions, has removed all jewelry and dentures, and is appropriately dressed for surgery.

Perform medication reconciliation. Certain home meds may be taken, especially beta-blockers. Check with health care provider and have patient take with a sip of water.

Inform anesthesia provider if patient is taking any herbal supplements.

Administer preprocedural medication, if applicable.

Postoperative Care

Check vital signs, including oxygen saturation, temperature, and pain score.

Administer oxygen, if necessary.

Change the patient’s position and progress activity—head of bed elevated, dangling, walking. Watch for dizziness or nausea.

Ascertain, using the following criteria, that the patient has recovered adequately to be discharged:

Vital signs stable and returned to preoperative level.

Stands without excessive dizziness; able to walk short distances.

Pain score within tolerable level (usually less than 3 required).

Able to drink fluids.

Oriented to time, place, and person.

No evidence of respiratory distress.

Has the services of a responsible adult who can escort the patient home and remain with patient.

Understands postoperative instructions and takes an instruction sheet home (see Patient Education Guidelines 7-1).

PATIENT EDUCATION GUIDELINES 7-1

Outpatient Postanesthesia and Postsurgery Instructions and Information

Although you will be awake and alert in the recovery room, small amounts of anesthetic will remain in your body for at least 24 hours and you may feel tired and sleepy for the remainder of the day. Once you are home, take it easy and rest as much as possible. It is advisable to have someone with you at home for the remainder of the day.

Eat lightly for the first 12-24 hours, then resume a well-balanced, normal diet. Drink plenty of fluids. Alcoholic beverages are to be avoided for 24 hours after your anesthesia or IV sedation.

Nausea or vomiting may occur in the first 24 hours. Lie down on your side and breathe deeply. Prolonged nausea, vomiting, or pain should be reported to your surgeon.

Ask your surgeon or anesthesiologist when you can resume your daily medications after surgery.

Your surgeon will discuss your postsurgery instructions with you and prescribe medication for you as indicated. You will also receive additional instructions specific to your surgical procedure before leaving the facility.

Your family will be waiting for you in the facility’s waiting room area near the outpatient surgery department. Your surgeon will speak to them in this area before your discharge.

Do not operate a motor vehicle or any mechanical or electrical equipment for 24 hours after your anesthesia.

Do not make any important decisions or sign legal documents for 24 hours after your anesthesia.

Informed Consent (Operative Permit)

Informed consent (operative permit) is the process of informing the patient about the surgical procedure; that is, risks and possible complications of surgery and anesthesia. Consent is obtained by the surgeon. This is a legal requirement. Hospitals usually have a standard operative permit form approved by the hospital’s legal department.

Purposes

To ensure that the patient understands the nature of the treatment, including potential complications and alternative treatment or procedures.

To indicate that the patient’s decision was made without pressure.

To protect the patient against unauthorized procedures, and to ensure that the procedure is performed on the correct body part.

To protect the surgeon and facility against legal action by a patient who claims that an unauthorized procedure was performed.

Adolescent Patient and Informed Consent

An emancipated minor is usually recognized as one who is not subject to parental control. Regulations vary by jurisdiction but generally include:

Married minor.

Those in military service.

Minor who has a child.

Most states have statutes regarding treatment of minors.

Standards for informed consent are the same as for adults.

Procedures Requiring Informed Consent and Time-Out

Any surgical procedures whether major or minor.

Entrance into a body cavity, such as colonoscopy, paracentesis, bronchoscopy, cystoscopy, or lumbar puncture.

Radiologic procedures, particularly if a contrast material is required (such as myelogram, magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, angiography).

All procedures requiring any type of anesthesia, which includes cardioversion.

Obtaining Informed Consent

Before signing an informed consent document, the patient should:

Be told in clear and simple terms by the surgeon what is to be done, the risks and benefits, as well as any alternatives to the surgery or procedure. The anesthesia care provider will explain the anesthesia plan and possible risks and complications.

Have a general idea of what to expect in the early and late postoperative periods.

Have a general idea of the time involved from surgery to recovery.

Have an opportunity to ask any questions.

Sign a separate form for each procedure or operation.

Written permission is required by law and a witness may be required according to facility policy.

Signature is obtained with the patient’s complete understanding of what is to occur; it is obtained before the patient receives sedation and is secured without pressure or duress.

For a minor (or a patient who is unconscious or irresponsible), permission is required from a responsible family member—parent, legal guardian, or court-appointed guardian.

For a married emancipated minor, permission from the spouse is acceptable.

If the patient is unable to write, an “X” is acceptable.

In an emergency, permission by way of telephone is acceptable.

Surgical Risk Factors and Preventive Strategies

Obesity

Danger

Increases the difficulty involved in the technical aspects of performing surgery; risk for wound dehiscence is greater.

Increases the likelihood of infection because of compromised tissue perfusion.

Increases the potential for postoperative pneumonia and other pulmonary complications because obese patients chronically hypoventilate.

Increases demands on the heart, leading to cardiovascular compromise.

Increases the risk for airway complications.

Alters the response to many drugs and anesthetics.

Decreases the likelihood of early ambulation.

Therapeutic Approach

Encourage weight reduction if time permits.

Anticipate postoperative obesity-related complications.

Be extremely vigilant for respiratory complications.

Carefully splint abdominal incisions when moving or coughing.

Be aware that some drugs should be dosed according to ideal body weight versus actual weight (owing to fat content) to prevent toxicity, including digoxin, lidocaine, aminoglycoside antibiotics, and theophylline.

Be aware that obese patients require higher doses of antibiotics to achieve effective tissue levels.

Avoid intramuscular (I.M.) injections in morbidly obese individuals (IV or subcutaneous routes preferred).

Never attempt to move an impaired patient without assistance or without using proper body mechanics.

Obtain a dietary consultation early in the patient’s postoperative course.

Poor Nutrition

Danger

Greatly impairs wound healing (especially protein and calorie deficits and a negative nitrogen balance).

Increases the risk of infection.

Therapeutic Approach

Any recent (within 4 to 6 weeks) weight loss of 10% of the patient’s normal body weight or decreased serum albumin should alert the health care staff to poor nutritional status and the need to investigate as to the cause of the weight loss.

Attempt to improve nutritional status before and after surgery. Unless contraindicated, provide a diet high in proteins, calories, and vitamins (especially vitamins C and A); this may require enteral and parenteral feeding.

Review a serum prealbumin level to determine recent nutritional status.

Recommend repair of dental caries and proper mouth hygiene to prevent infection.

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance

Danger

Can have adverse effects in terms of general anesthesia and the anticipated volume losses associated with surgery, causing shock and cardiac dysrhythmias.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTPatients undergoing major abdominal operations (such as colectomies and aortic repairs) often experience a massive fluid shift into tissues around the operative site in the form of edema (as much as 1 L or more may be lost from circulation). Watch for the fluid shift to reverse (from tissue to circulation) around the third postoperative day. Patients with heart disease may develop failure due to the excess fluid “load.”

Therapeutic Approach

Assess the patient’s fluid and electrolyte status.

Rehydrate the patient parenterally and orally as prescribed.

Monitor for evidence of electrolyte imbalance, especially Na+, K+, Mg++, Ca++.

Be aware of expected drainage amounts and composition; report excess and abnormalities.

Monitor the patient’s intake and output; be sure to include all body fluid losses.

Aging

Danger

Potential for injury is greater in older people.

Be aware that the cumulative effect of medications is greater in the older patient.

Medications in the usual dosages, such as morphine, may cause confusion, disorientation, and respiratory depression.

Therapeutic Approach

Consider using lesser doses for desired effect.

Anticipate problems from chronic disorders such as anemia, obesity, diabetes, hypoproteinemia.

Adjust nutritional intake to conform to higher protein and vitamin needs.

When possible, cater to set patterns in older patients, such as sleeping and eating.

Presence of Cardiovascular Disease

Danger

May compound the stress of anesthesia and the operative procedure.

May result in impaired oxygenation, cardiac rhythm, cardiac output, and circulation.

May also produce cardiac decompensation, sudden arrhythmia, thromboembolism, acute myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiac arrest.

Holding cardiac medications, particularly beta-blockers, may have negative impact on cardiac status.

Therapeutic Approach

Frequently assess heart rate and blood pressure (BP) and hemodynamic status and cardiac Rhythm, if indicated.

Avoid fluid overload (oral, parenteral, blood products) because of possible MI, angina, heart failure, and pulmonary edema.

In compliance with SCIP measures, make sure the patient has not held beta-blocker prior to surgery. Administer with a sip of water.

Prevent prolonged immobilization, which results in venous stasis. Monitor for potential deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolus.

Encourage position changes but avoid sudden exertion.

Use anti-embolism stockings and/or sequential compression device intraoperatively and postoperatively.

Note evidence of hypoxia and initiate therapy.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAmerican Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. (2011). 2010-2012 standards of perianesthesia nursing practice. Cherry Hill, NJ: Author.

Presence of Diabetes Mellitus

Danger

Hypoglycemia may result from food and fluid restrictions and anesthesia.

Hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis may be potentiated by increased catecholamines and glucocorticoids due to surgical stress.

Chronic hyperglycemia results in poor wound healing and susceptibility to infection.

Research has shown that surgical patients have better outcomes when glucose levels are well controlled throughout the surgical process.

Therapeutic Approach

Recognize the signs and symptoms of ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia, which can threaten an otherwise uneventful surgical experience. Dehydration also threatens renal function.

Monitor blood glucose and be prepared to administer insulin, as directed, or treat hypoglycemia.

Confirm what medications the patient has taken and what has been held. Facility protocol and provider preference varies, but the goal is to prevent hypoglycemia. If the patient is NPO, oral agents are usually withheld and insulin may be ordered at 75% of the usual dose.

Reassure the diabetic patient that when the disease is controlled, the surgical risk is no greater than it is for the nondiabetic patient.

DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERTRare reports of lactic acidosis have raised concerns about the use of metformin in the perioperative period. Metformin is usually held 48 hours before surgery and restarted when full food and fluid intake has restarted and normal renal function has been confirmed.

Presence of Alcoholism

Danger

The additional problem of malnutrition may be present in the presurgical patient with alcoholism. The patient may also have an increased tolerance to anesthetics.

Therapeutic Approach

Note that the risk of surgery is greater for the patient who has chronic alcoholism.

Anticipate the acute withdrawal syndrome within 72 hours of the last alcoholic drink.

Presence of Pulmonary and Upper Respiratory Disease

Danger

Chronic pulmonary illness may contribute to hypoventilation, leading to pneumonia and atelectasis.

Surgery may be contraindicated in the patient who has an upper respiratory infection because of the possible advance of infection to pneumonia and sepsis.

Sleep apnea in the perioperative patient provides a great risk to anesthesia and must be noted and assessed prior to surgery.

Therapeutic Approach

Patients with chronic pulmonary problems, such as emphysema or bronchiectasis, should be evaluated and treated prior to surgery to optimize pulmonary function with bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and conscientious mouth care, along with a reduction in weight and smoking and methods to control secretions.

Patients with obstructive sleep apnea should be evaluated by an anesthesia provider prior to surgery. General anesthesia should be avoided if possible. Patients should bring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines to the hospital for use post-anesthesia.

Opioids should be used cautiously to prevent hypoventilation. Patient-controlled analgesia is preferred.

Oxygen should be administered to prevent hypoxemia (low liter flow in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Concurrent or Prior Pharmacotherapy

Danger

Hazards exist when certain medications are given concomitantly with others (eg, interaction of some drugs with anesthetics can lead to hypotension and circulatory collapse). This also includes the use of many herbal substances. Although herbs are natural products, they can interact with other medications used in surgery.

Therapeutic Approach

An awareness of drug therapy is essential.

Notify the health care provider and anesthesia provider if the patient is taking any of the following drugs:

Certain antibiotics.

Antidepressants, particularly monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and St. John’s wort, an herbal product.

Phenothiazines.

Diuretics, particularly thiazides.

Corticosteroids.

Anticoagulants, such as warfarin or heparin, or medications or herbals that may affect coagulation, such as aspirin, feverfew, ginkgo biloba, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine, and clopidogrel.

PREOPERATIVE CARE

Patient Education

Patient education is a vital component of the surgical experience. Preoperative patient education may be offered through conversation, discussion, the use of audiovisual aids, demonstrations, and return demonstrations. It is designed to help the patient understand the surgical experience to minimize anxiety and promote full recovery from surgery and anesthesia. The educational program may be initiated before hospitalization by the physician, nurse practitioner or office nurse, or other designated personnel. This is particularly important for patients who are admitted the day of surgery or who are to undergo outpatient surgical procedures. The perioperative nurse can assess the patient’s knowledge base and use this information in developing a plan for an uneventful perioperative course.

Teaching Strategies

Obtain a Database

Determine what the patient already knows or wants to know. This can be accomplished by reading the patient’s chart, interviewing the patient, and communicating with the health care provider, family, and other members of the health care team.

Ascertain the patient’s psychosocial adjustment to impending surgery.

Determine cultural or religious health beliefs and practices that may have an impact on the patient’s surgical experience, such as refusal of blood transfusions, burial of amputated limbs within 24 hours, or special healing rituals.

Plan and Implement Teaching Program

Begin at the patient’s level of understanding and proceed from there.

Plan a presentation, or series of presentations, for an individual patient or a group of patients.

Include family members and significant others in the teaching process.

Encourage active participation of patients in their care and recovery.

Demonstrate essential techniques; provide the opportunity for patient practice and return demonstration.

Provide time for and encourage the patient to ask questions and express concerns; make every effort to answer all questions truthfully and in basic agreement with the overall therapeutic plan.

Provide general information and assess the patient’s level of interest in or reaction to it.

Explain the details of preoperative preparation and provide a tour of the area and view the equipment when possible.

Offer general information on the surgery. Explain that the health care provider is the primary resource person.

Notify the patient when surgery is scheduled (if known) and approximately how long it will take; explain that afterward the patient will go to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Emphasize that delays may be attributed to many factors other than a problem developing with this patient (eg, previous case in the operating room may have taken longer than expected or an emergency case has been given priority).

Let the patient know that his or her family will be kept informed and that they will be told where to wait and when they can see the patient; note visiting hours.

Explain how a procedure or test may feel during or afterward.

Describe the PACU and what personnel and equipment the patient may expect to see and hear (specially trained personnel, monitoring equipment, tubing for various functions, and a moderate amount of activity by nurses and health care providers).

Stress the importance of active participation in postoperative recovery.

Use other resource people: health care providers, therapists, chaplain, interpreters.

Document what has been taught or discussed as well as the patient’s reaction and level of understanding.

Discuss with the patient the anticipated postoperative course (eg, length of stay, immediate postoperative activity, followup visit with the surgeon).

Use Audiovisual Aids If Available

Videotapes or computer programs are effective in giving basic information to a single patient or group of patients. Many facilities provide a television channel dedicated to patient instruction.

Booklets, brochures, and models, if available, are helpful.

Demonstrate any equipment that will be specific for the particular patient. Examples:

Drains and drainage bags

Monitoring equipment

Side rails

Incentive spirometer

Sequential compression device

General Instructions

Preoperatively, the patient will be instructed in the following postoperative activities. This will allow a chance for practice and familiarity.

Incentive Spirometry

Preoperatively, the patient uses a spirometer to measure deep breaths (inspired air) while exerting maximum effort. The preoperative measurement becomes the goal to be achieved as soon as possible after the operation.

Postoperatively, the patient is encouraged to use the incentive spirometer about 10 to 12 times per hour.

Deep inhalations expand alveoli, which prevents atelectasis and other pulmonary complications.

There is less pain with inspiratory concentration than with expiratory concentration such as with coughing.

Coughing

Coughing promotes the removal of chest secretions. Instruct the patient to:

Interlace fingers and place hands over the proposed incision site; this will act as a splint during coughing and not harm the incision.

Lean forward slightly while sitting in bed.

Breathe, using the diaphragm.

Inhale fully with the mouth slightly open.

Let out three or four sharp “hacks.”

With the mouth open, take in a deep breath and quickly give one or two strong coughs.

Secretions should be readily cleared from the chest to prevent respiratory complications (pneumonia, obstruction).

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTIncentive spirometry, deep breathing, and coughing, as well as certain position changes, may be contraindicated after some surgeries (eg, craniotomy and eye or ear surgery).

Turning

Changing positions from back to side-lying (and vice versa) stimulates circulation, encourages deeper breathing, and relieves pressure areas.

Help the patient to move onto his or her side if assistance is needed.

Place the uppermost leg in a more flexed position than that of the lower leg, and place a pillow comfortably between the legs.

Make sure that the patient is turned from one side to the back and onto the other side every 2 hours.

Foot and Leg Exercises

Moving the legs improves circulation and muscle tone.

Have the patient lie supine; instruct patient to bend a knee and raise the foot—hold it a few seconds, and lower it to the bed.

Repeat above about five times with one leg and then with the other. Repeat the set five times every 3 to 5 hours.

Then have the patient lie on one side and exercise the legs by pretending to pedal a bicycle.

Suggest the following foot exercise: Trace a complete circle with the great toe.

Evaluation of Teaching Program

Observe the patient for correct demonstration of expected postoperative behaviors, such as foot and leg exercises and special breathing techniques.

Ask pertinent questions to determine the patient’s level of understanding.

Reinforce information when necessary.

Preparation of the Operative Area

Skin Antisepsis

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAlexander, J. W., Solomkin, J. S., & Edwards, M. J. (2011). Updated recommendations for control of surgical site infections. Annals of Surgery, 253, 1082-1093.

Human skin normally harbors transient and resident bacterial flora, some of which are pathogenic. Skin cannot be sterilized without destroying skin cells.

The attributes of an appropriate surgical skin antiseptic require the ability to significantly reduce microorganisms, provide broad spectrum activity, be fast acting, and have a persistent effect.

Preoperative bathing with chlorhexidine reduces pathogenic organisms on the skin. Using multiple showers or showers immediately before coming to the operating room substantially reduces skin organisms.

Cleansing with a bactericidal-impregnated sponge just before operation will provide additional reduction in skin bacteria.

Friction enhances the action of detergent antiseptics; however, friction should not be applied over a superficial malignancy (causes seeding of malignant cells) or areas of carotid plaque (causes plaque dislodgment and emboli).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that hair not be removed near the operative site unless it will interfere with surgery. Skin is easily injured during shaving and often results in a higher rate of postoperative wound infection.

If required, hair removal should be done by clipping, not shaving, and should be performed within 2 hours of surgery. Scissors may be used to remove hair greater than 3 mm in length.

For head surgery, obtain specific instructions from the surgeon concerning the extent of shaving.

Gastrointestinal Tract

Preparation of the bowel is imperative for patients undergoing intestinal surgery because escaping bacteria can invade adjacent tissues and cause sepsis.

Cathartics and enemas remove gross collections of stool (eg, GoLYTELY).

Oral antimicrobial agents (eg, neomycin, erythromycin) suppress the colon’s potent microflora.

Enemas “until clear” are generally not necessary. If ordered, they are given the night before surgery. Notify the health care provider if the enemas never return clear.

Solid food is withheld from the patient for 6 hours before surgery. Patients having morning surgery are kept NPO overnight. Clear fluids (water) may be given up to 4 hours before surgery depending on facility protocols.

Genitourinary Tract

A medicated douche may be prescribed preoperatively if the patient is to have a gynecologic or urologic operation.

Preoperative Medication

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAlexander, J. W., Solomkin, J. S., & Edwards, M. J. (2011). Updated recommendations for control of surgical site infections. Annals of Surgery, 253, 1082-1093.

With the increase of ambulatory surgery and same-day admissions, preanesthetic sedatives, skin preps, and douches are seldom ordered. Administration of systemic prophylactic perioperative antibiotics is among one of the most important steps in preventing surgical site infection, however. Recent evidence shows that the use of prophylactic antibiotics decreases the incidence of wound infections by about one half. There is a risk, however, of an increase in Clostridium difficile diarrheal infections due to antibiotic use. Redosing of antibiotics should be done every 3 hours during surgery and should be discontinued within 24 hours after surgery end time (48 hours for cardiac surgeries).

DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERTAntibiotics should be administered just before surgery—preferably 1 hour before an incision is made—to be effective when bacterial contamination is expected.

Administering “On Call” Medications

Have the medication ready and administer it as soon as the call is received from the operating room.

Proceed with the remaining preparation activities.

Indicate on the chart or preoperative checklist the time when the medication was administered and by whom.

Admitting the Patient to Surgery

Final Checklist

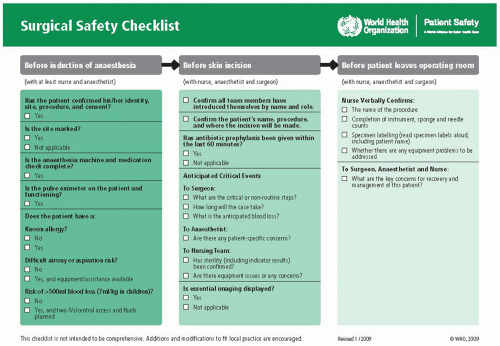

The preoperative checklist is the last procedure before taking the patient to the operating room. Most facilities have a standard form for this checklist. The World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist is available for hospital use. It does not, however, remove the nurse’s responsibility for the hospital’s specific checklist that may be in use (see Figure 7-2).

Identification and Verification

This includes verbal identification by the perioperative nurse while checking the identification band on the patient’s wrist and written documentation (such as the chart) of the patient’s identity, the procedure to be performed (laterality, if indicated), the specific surgical site marked by the surgeon with indelible ink, the surgeon, and the type of anesthesia. These are all patient safety goals as outlined by the Joint Commission.

Review of Patient Record

Check for inclusion of the fact sheet; allergies; history and physical; completed preoperative checklist; laboratory values, including most recent results, pregnancy test, if applicable; electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest x-rays, if necessary; preoperative medications; and other preoperative orders by either the surgeon or anesthesia care provider.

Consent Form

All nurses involved with patient care in the preoperative setting should be aware of the individual state laws regarding informed consent and the specific facility policy. Obtaining informed consent is the responsibility of the surgeon performing the specific procedure. Consent forms should state the procedure, various risks, and alternatives to surgery, if any. It is a nursing responsibility to make sure the consent form has been obtained with the patient or guardian’s signature and that it is in the chart.

Patient Preparedness

NPO status.

Proper attire (clean gown and hair covering) and clean linen.

Skin preparation, if ordered.

IV line started with correct gauge needle.

Dentures or plates removed.

Jewelry, piercings, contact lenses, and glasses removed and secured in a locked area or given to a family member.

Allow the patient to void.

Transporting the Patient to the Operating Room

Adhere to the principle of maintaining the comfort and safety of the patient.

Accompany operating room attendants to the patient’s bedside for introduction and proper identification.

Assist in transferring the patient from bed to stretcher (unless the bed goes to the operating room floor).

Complete the chart and preoperative checklist; include laboratory reports and x-rays as required by facility policy or the health care provider’s directive.

Make sure that the patient arrives in the operating room at the proper time.

The Patient’s Family

Direct the patient’s family to the proper waiting room where magazines, television, and a coffee station may be available.

Tell the family that the surgeon will probably contact them there after surgery to inform them about the operation.

Inform the family that a long interval of waiting does not mean the patient is in the operating room the whole time; anesthesia preparation and induction take time, and after surgery, the patient is taken to the PACU.

Tell the family what to expect postoperatively when they see the patient—tubes; monitoring equipment; and blood transfusion, suctioning, and oxygen equipment.

INTRAOPERATIVE CARE

Anesthesia and Related Complications

The goals of anesthesia are to provide analgesia, sedation, and muscle relaxation appropriate for the type of operative procedure as well as to control the autonomic nervous system.

Common Anesthetic Techniques

Moderate Sedation

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAssociation of periOperative Registered Nurses. (2011). Recommended practice for managing the patient receiving moderate sedation/analgesia. Denver, CO: Author.

A specific level of sedation that allows patients to tolerate unpleasant procedures by reducing the level of anxiety and discomfort; previously known as conscious sedation.

The patient achieves a depressed level of consciousness (LOC) and altered perception of pain while retaining the ability to respond appropriately to verbal and tactile stimuli.

Cardiopulmonary function and protective airway reflexes are maintained by the patient.

Knowledge of expected outcomes is essential. These outcomes include, but are not limited to:

Maintenance of consciousness.

Maintenance of protective reflexes.

Alteration of pain perception.

Enhanced cooperation.

Adequate preoperative preparation of the patient will facilitate achieving the desired effects.

Nurses caring for patients receiving moderate sedation should be specially trained in the agents used for moderate sedation, such as midazolam and fentanyl, and should be skilled in advanced life support. Many facilities have strict regulations and training requirements for staff handling such patients.

Nurses working in this setting should also be aware of the regulations from the Board of Nursing in the state they are practicing concerning the care of patients receiving anesthesia and should be compliant with state advisory opinions, declaratory rules, and other regulations that direct the practice of the registered nurse.

Patients who are not candidates for conscious sedation and require more complex sedation should be managed by anesthesia care providers.

Monitored Anesthesia Care

Light to deep sedation that is monitored by an anesthesia care provider.

The patient is asleep but arousable.

The patient is not intubated.

The patient may receive local anesthesia and oxygen, is monitored, and receives sedation and analgesia. Midazolam, fentanyl, alfentanil, and propofol are frequently used in monitored anesthesia care procedures.

General Anesthesia

A reversible state consisting of complete loss of consciousness. Protective reflexes are lost.

With the loss of protective reflexes, the patient’s airway needs to be maintained. This can be done by endotracheal intubation or insertion of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA).

For certain, short and uncomplicated surgeries (eg, myringotomies), the insertion of a breathing tube may not be necessary, and the airway is maintained manually with a jaw-thrust/chin-lift.

Endotracheal (ET) intubation is facilitated by the use of a laryngoscope. The ET tube is inserted into the trachea and passed through the vocal cords. A cuff is then inflated, thus ensuring a secure airway where no secretions from the oral cavity can enter the lungs.

LMA does not require a laryngoscope for insertion and is inserted only to the entrance of the trachea. Although LMA does not provide a totally protected airway, it is noninvasive and more gentle on the tissue.

General anesthesia consists of three phases; induction, maintenance, and emergence.

Induction can be accomplished either by parenteral or inhalation route. Common agents for IV induction are propofol and phenobarbital. In addition to the induction agent, a potent analgesic is also often added (eg, fentanyl). The analgesic potentiates the induction agent as well as provides analgesia. Patients can also reach an unconscious state by inhaling a potent, short-acting volatile gas. Sevoflurane is one such example. Once the patient is asleep, and if the surgical procedure so requires, a muscle relaxant is given and the ET tube is inserted. Common muscle relaxants include vecuronium, rocuronium, and succinylcholine.

Maintenance is accomplished through a continuous delivery of an inhalation agent, such as sevoflurane, isoflurane, or desflurane, or an IV infusion of an agent, such as propofol, to maintain an unconscious state. Intermittent doses of an analgesic are given as needed as well as intermittent doses of a muscle relaxant for longer surgeries.

Emergence occurs at the end of the surgery when the continuous delivery of either the gas or the IV infusion is stopped and the patient slowly returns to a conscious state. If muscle relaxants are still in effect, they can be reversed with neostigmine to allow for adequate muscle strength and return of spontaneous ventilations. A nerve stimulator can be used to assess if adequate muscle control has returned before extubation of the trachea. During emergence, the patient is very sensitive to any stimuli and it is important to keep noise levels to a minimum and refrain from manipulating the patient during this stage.

Regional Anesthesia

Examples of regional anesthesia include spinal, epidural, and peripheral blocks (eg, interscalene blocks, ankle-blocks).

Anesthesia is achieved by injecting a local anesthetic, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine, in close proximity to appropriate nerves.

Nursing responsibilities include being familiar with the drug used and maximum dose that can be given, knowing signs and symptoms of toxicity, and maintaining a comfortable environment for the conscious patient.

Spinal anesthesia is the injection of a local anesthetic into the lumbar intrathecal space. The anesthetic blocks conduction in spinal nerve roots and dorsal ganglia, thereby causing paralysis and analgesia below the level of injection.

Epidural anesthesia involves injecting local anesthetic into the epidural space. Results are similar to spinal analgesia but with a slower onset.

Often a catheter is inserted for continuous infusion of the anesthetic to the epidural space.

The catheter may be left in place to provide postoperative analgesia as well.

Peripheral nerve block is achieved by injecting a local anesthetic into a bundle of nerves (eg, axillary plexus) or into a single nerve to achieve anesthesia to a specific part of the body (eg, hand or single finger).

Intraoperative Complications

Hypoventilation and hypoxemia—due to inadequate ventilatory support.

Oral trauma (broken teeth, oropharyngeal, or laryngeal trauma)—due to difficult ET intubation.

Hypotension—due to preoperative hypovolemia or untoward reactions to anesthetic agents.

Cardiac dysrhythmia—due to preexisting cardiovascular compromise, electrolyte imbalance, or untoward reactions to anesthetic agents.

Hypothermia—due to exposure to a cool ambient operating room environment and loss of normal thermoregulation capability from anesthetic agents.

Peripheral nerve damage—due to improper positioning of the patient (eg, full weight on an arm) or use of restraints.

Malignant hyperthermia.

This is a rare reaction to anesthetic inhalants (notably sevoflurane, enflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane) and the muscle relaxant succinylcholine.

Caused by abnormal and excessive intracellular accumulations of calcium with resulting hypermetabolism, increased muscle contraction, and elevated body temperature.

Treatment consists of discontinuing the inhalant anesthetic, administering IV dantrolene, and applying cooling techniques (eg, cooling blanket, iced saline lavages).

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTRecognize malignant hyperthermia immediately so that inhalant anesthesia can be discontinued and treatment measures started, to prevent seizures and other adverse effects.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Postanesthesia Care Unit

To ensure continuity of care from the intraoperative phase to the immediate postoperative phase, the circulating nurse or anesthesia care provider gives a thorough report to the PACU nurse (see Standards of Care Guidelines 7-1). This report should include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree