Chapter 27 Perineal care and repair

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To understand the historical background to the midwife’s role in perineal care and repair

2. To understand evidence-based methods for the prevention of perineal and pelvic floor damage, and in particular midwifery strategies for minimising perineal trauma and improving second-stage comfort

3. To be able to identify the structures of the pelvic floor and its importance in midwifery practice

4. To identify degrees and types of perineal trauma, and understand what is in the scope of practice of a midwife, when to consult a more experienced practitioner, and when to refer

5. To understand when and how to perform an episiotomy

6. To understand the principles of safe, effective perineal repair

7. To be able to give women appropriate, evidence-based advice regarding care of perineal trauma and pelvic floor in the immediate postpartum period.

Perineal trauma can have lifelong effects on the quality of women’s lives. Midwives should try to minimise this trauma, and after correctly identifying it should be able to undertake perineal repair competently, using the best suturing techniques and materials, to minimise any associated short- and long-term morbidity. Prevention of perineal trauma and improvement of second-stage comfort are important components of perineal care. The pelvic floor is the term given to the structures that fill the outlet of the bony pelvis. These muscles have important functions, and disruption to their integrity can have serious consequences for a woman’s health. It is important for a midwife to have an understanding of the structure and function of the pelvic floor muscles and perineal body in order to minimise damage and prevent long-term morbidity.

Care and advice given to the woman, following the birth, regarding her perineum and pelvic floor is often not evidence-based and in some cases remains virtually absent. It is important for a woman to have the best possible support and advice in the postnatal period in order to be able to care for herself and ensure optimal perineal and pelvic floor muscle health. The midwife’s role in giving support and evidence-based advice in the antenatal and postnatal periods can ensure that women minimise long-term morbidity, such as incontinence and sexual dysfunction.

These pages have not been written for those who lay them aside saying or thinking, ‘much ado about a perineal tear!’ They will have to come to terms with their own consciences. (Ritgen 1885, p 321)

BACKGROUND

Both childbearing women and healthcare professionals place a high value on minimising perineal trauma and reducing potential associated morbidity (Homer & Dahlen 2007). However, countries report wide variations in trauma rates and the rates also vary within individual countries; further variations exist among institutions and healthcare professionals (Renfrew et al 1998). In studies where the use of episiotomy is restricted, 55%–77% of women still sustained perineal trauma significant enough to require suturing (Albers et al 1999; Mayerhofer et al 2002; McCandlish et al 1998). In Australia, around 65% of women have some form of perineal trauma and around 15% have an episiotomy (Laws & Hilder 2008). It is apparent that trauma to the genital tract commonly accompanies vaginal birth (Williams et al 1998) and it is known to be more common in primiparous women (Macarthur & Macarthur 2004). Numerous factors have been suggested as potential contributors to perineal trauma, as have numerous solutions for minimisation of that trauma (Kettle 2004; Klein et al 1997; McCandlish et al 1998). Some of these contributors and solutions are based on sound evidence, but many others are not. There is also evidence that perineal trauma was not always as high as it appears today, leading one to question contemporary second-stage management—both the complex package of care and individual elements in that care (De Wees 1889; Ritgen 1885; Thacker & Banta 1983).

Perineal preservation and perineal comfort during the second stage of labour are important goals in the practice of most midwives. Furthermore, both midwives and obstetricians are aware that perineal trauma is associated with significant short- and long-term morbidity for women following childbirth (Glazener et al 1995; McCandlish et al 1998; Sleep & Grant 1987). Women who have an intact perineum after the birth of their first baby have stronger pelvic floor muscles (measured by electromyogram) and make a quicker muscle recovery than women experiencing tears or episiotomies (Klein et al 1994). While perineal trauma has not been clearly associated with urinary incontinence (Woolley 1995), severe perineal trauma (third- and fourth-degree tears) has been shown to be associated with faecal incontinence (Sultan & Thakar 2002). Acute postpartum perineal pain is common among women who give birth vaginally and its severity is linked to that of the perineal injury (Albers et al 1999; Kenyon & Ford 2004; Klein et al 1994). Perineal pain can have long- and short-term negative consequences for women’s health and wellbeing (Albers et al 1999; Glazener et al 1995; Klein et al 1994; McCandlish et al 1998; Sleep & Grant 1987). It can make everyday activities such as sitting, walking, voiding, defecating, providing self-care and caring for the baby, including breastfeeding, extremely difficult. It can also lead to relationship disharmony and sexual disorders that can lead to irritability, resentment, depression and maternal exhaustion (Barrett et al 2000; Greenshields & Hulme 1993; Klein et al 1994; Signorello et al 2001; Sleep & Grant 1987; Steen et al 2000; Steen & Marchant 2001).

Perineal pain experienced during the second stage of labour can also have an impact on how a woman views her birth experience. Women report that the advancement of the baby’s head, and stretching of the perineum in the minutes before giving birth, are accompanied by pain that can be severe (Lowe & Roberts 1998; Mander 1992; Miller 1994; Niven & Gijsbers 1984; Stewart 1982), and this can lead to women remembering the second stage in a particularly negative light (McKay et al 1990). In the developed world there has been a dramatic increase in caesarean section rates in the last decade. Fear of the pain associated with labour as well as perineal injury are reported as reasons why women may request a caesarean section (Kolas et al 2003; Nerum et al 2006). Methods of reducing pain and trauma during the second stage, without having to resort to potentially harmful pharmacological pain relief or major abdominal surgery, would be beneficial to women and indeed to society as a whole. It is curious to observe that much of the research on pain in labour has focused on the first stage, thus largely overlooking the pain associated with the actual birth (Sanders et al 2005). This is why perineal care packages should always consider second-stage comfort as a key component.

Historical perspectives

The physician Soranus of Ephesus (98–138 AD) produced one of the most important treatises on obstetrics (Carter & Duriez 1986). It was called Gynaecology and was written specifically for midwives (Temkin 1956). One of the earliest writers to describe the care of the perineum, Soranus gave instructions that the midwife should support the perineum with a linen pad while the head is advancing and advised an attendant to stand behind the midwife’s stool and place a ‘pledget’ underneath in order to restrain the anus and avoid prolapse and rupture that can accompany straining (Temkin 1956). Attempts to reduce perineal trauma, carry out repairs on it and improve comfort in the second stage appears to pre-date known written texts. For example, sutures may have been used for thousands of years, the eyed needle being invented somewhere between 50,000 and 30,000 BC (Mackenzie 1973).

During the 11th century AD Trota (or Trocta) became one of the first women to write a text on the subject of obstetrics (Trotula), although some historians propose that a man in fact wrote Trotula, or several men assuming a woman’s name (Green 2002; O’Dowd & Philipp 2000). Trota’s works draw heavily on the works of Soranus and again instruct the midwife to support the perineum with a linen pad. They give a full description of severe perineal trauma that can occur when neglecting this precaution, something that is currently not supported by research. They also describe how to repair the trauma with silk sutures (Green 2002; King & Rabil 2005; Trotula 1940). Graham (1950) writes that this is the first time in history that a complete perineal repair is recommended.

We are also provided with glimpses into the management of childbirth by well-known midwives, such as German midwife Justine Siegemund (1636–1706 AD), French midwife Louise Bourgeois (1563–1636 AD), Frisian midwife Catharina Schrader (1693–1740 AD) and English midwives Sarah Stone (1600s) and Elizabeth Nihell (1700s) (Dahlen 2007a). Most of these midwives advocate protection of the perineum.

You certainly should not stretch or dilate anything with your fingers. This is a common mistake. This sharp stretching injures the woman’s belly and causes swelling before the child gets that far and comes forth. (Siegemund 2005, p 74)

French midwife Madame du Coudray, known as the ‘King’s Midwife’, was famous for developing the first obstetric mannequin and for her tours around the French countryside educating midwives, with the King’s blessing, between 1760 and 1783 (Gelbart 1998). Like Siegemund, she warns against ‘too much vaginal meddling … the best thing is to wait patiently, alert to all cues’ (Gelbart 1998, p 33). Madame du Coudray, using her mannequin, spent many days teaching her students about ‘natural delivery’ and providing the students with techniques for facilitating the baby’s ‘slippery exit’:

Although great science is not necessary in natural delivery there are still plenty of precautions to take during labor to ensure that favorable beginnings do not end badly. (Gelbart 1998, pp 68–69)

Sir Fielding Ould altered care of the perineum dramatically in 1742 when he gave the first description of episiotomy. While no doubt this practice was used only occasionally at first, eventually it became the most common form of obstetric surgery (Kitzinger & Simkin 1984). At times, perineal care moved clearly away from prevention of perineal trauma into deliberate surgical intervention. This was accompanied by increased use of a supine birth position, forceps, obstetric anaesthesia and episiotomy that all led to poorer outcomes for women and their perineum.

There is evidence that perineal trauma was not always as high as it appears today, leading to questions around contemporary second-stage management. De Wees, in 1889, for example, reported only 51 lacerations in 1000 consecutive births (5.1%) (De Wees 1889), while Ritgen, in 1885, described the exact length of 190 tears occurring during the births of 4875 women (3.9%) (Ritgen 1885).

It has been observed that the rise in episiotomy rates in the United States was directly proportional to the move from birth at home to birth in hospital (Thacker & Banta 1983). In the US in 1930, approximately 25% of women gave birth in hospital compared with 70% in 1945. The rate of episiotomy is thought to reflect this shift in the environment of birth and the resulting dominant surgical model of care (Thacker & Banta 1983).

MIDWIVES AND PERINEAL REPAIR

In recent years, the role of the midwife has been extended to incorporate a broader range of clinical skills into practice. Perineal repair is one of these skills. Midwives are increasingly expected to undertake perineal repair on their own responsibility and to provide women with advice regarding perineal care. This falls within the scope of practice for a midwife (ICM 2005). Women prefer to be sutured by the same professional who assisted with the birth (Ho 1985; Hulme & Greenshields 1993; Sullivan 1991). This is due to many factors, including decreased waiting times, continuity of care, empathy and receiving good information regarding expected outcomes and care of the repaired perineum during the postnatal period.

The way perineal repair is taught to midwives and the supervision, accreditation and frequency of updates for these healthcare professionals is managed differently in different organisations and under different models of care. For example, in midwifery-led units and birth centres, the proportion of midwives performing perineal repairs appears to be higher than in traditional labour ward settings (Dahlen 2004).

While the type of suturing material and technique of the repair is important, the skill of the operator has also been recognised as one of three main factors that influence the outcome of perineal repair (Greentop Guideline No. 24, RCOG 2004). The guideline states that practitioners who are appropriately trained are more likely to provide a consistent and high standard of perineal repair (Greentop Guideline No. 24, RCOG 2004). It also recommends 24-hour cover by an experienced practitioner to facilitate training and provide support and supervision (RCOG 2004). A UK survey highlighted the deficiency and dissatisfaction among trainee doctors and midwives with their training in perineal anatomy and repair (Sultan et al 1995). Despite this, much perineal repair research is focused on suture material and technique rather than on skill or training. Draper and Newell (1996) studied the consequences and outcomes of midwifery management of perineal trauma, and found that the skill of the operator, regardless of profession (doctor, midwife, student midwife),was the most important factor for a successful repair, and was probably more important than the method chosen or the material used. This is supported by findings from other research (Grant 1989; Sleep et al 1984).

In a study undertaken to explore Australian midwives’ attitudes relating to perineal repair, respondents strongly supported the incorporation of perineal repair into midwifery practice (Dahlen & Homer 2008b). The most important reason given for midwives undertaking perineal repair was that it provides continuity of care; the second most important reason was because it is part of their professional role. Three-quarters of respondents in the study felt that student midwives should have practical experience with perineal repair during their training. The study found that there was strong support for midwives and doctors to undertake perineal repair training together. In addition, there was support to move back to a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach where both doctors and midwives teach and learn together. This would provide an opportunity for both professions to share skills and learn together, potentially enhancing collaboration and possibly leading to a greater consistency in practice.

The study also found that confidence in carrying out perineal repairs was associated with experience (Dahlen & Homer 2008b). More-experienced midwives were more confident and enjoyed undertaking the procedure. This is reassuring for midwives who are beginners in perineal repair. It is important for midwives to know that the more skilled they become, the more confident they will be and they will experience more satisfaction as a result. Experience also lessens worry about the quality of the procedure and the impact it has on women. All these factors can influence midwives’ enthusiasm in learning this important skill. Reassurance is needed that practice not only makes perfect but also makes the skill more enjoyable and rewarding.

Risk factors for perineal trauma

Perineal trauma commonly accompanies vaginal birth, and can result from intentional trauma (episiotomy), non-intentional trauma (tears and grazes), or both (Renfrew et al 1998). Trauma to the genital tract is more common in primiparous women (Williams et al 1998) and with operative vaginal deliveries (Macarthur & Macarthur 2004). Countries report wide variations in trauma rates. Episiotomy, for example, ranges from as low as 10% in some countries to nearly 100% in others, thus demonstrating huge variation in practice which results in diverse rates of perineal trauma for women (Graham et al 2005).

Numerous factors have been suggested as potential contributors to perineal trauma. These include maternal and fetal factors such as maternal nutritional status, body mass, parity, history of prior trauma, ethnicity, older age, abnormal collagen synthesis, baby’s birthweight, fetal malposition and malpresentation. Second-stage management can also have an influence on perineal trauma and maternal comfort during the actual birth. These include continuous support, maternal position, style of pushing, techniques to relax the perineum, episiotomy, hand manoeuvres, vacuum versus forceps delivery, immersion in water and epidurals (due to the associated risk of instrumental birth) (Kettle 2004; Klein et al 1997; McCandlish et al 1998). Perineal trauma is reported to be lower for women who give birth at home (Murphy & Feinland 1998) and higher for women who are attended by obstetricians (Roberts et al 2000; Shorten et al 2002), with rates varying within professional groups and between individual clinicians (Klein et al 1992; Logue 1991; Wilkerson 1984).

A systematic review of practices to minimise trauma to the genital tract in childbirth found that motivation, confidence, control and pain tolerance had not been specifically addressed by research (Renfrew et al 1998). The impact of fear and lack of communication on perineal outcome warrants further study (Dahlen et al 2007b).

There are also specific risk factors for severe perineal trauma that midwives need to be aware of (Box 27.1).

Box 27.1 Risk factors for severe perineal trauma

Preventing perineal trauma and improving second-stage comfort

A systematic review was recently undertaken in order to identify beneficial practices for reducing perineal trauma and/or improving comfort during the second stage of labour (Dahlen 2007a). In total, 194 papers were incorporated into the literature review. This included 20 systematic reviews, 132 randomised trials and quasi-randomised trials, 27 prospective cohorts and 15 other studies. The evidence supports benefits for women with regards to perineal trauma and/or second-stage comfort from: the use of digital antenatal perineal massage; application of perineal warm packs in the second stage; giving birth in an upright or lateral position; advising women to follow their own urges to push during the second stage; having some control of the baby’s head during the birth; using a vacuum extractor in preference to forceps; restricting the use of episiotomy; avoiding an epidural where possible; supporting women throughout labour and birth; giving birth in a home-like environment or at home; and giving birth with midwives compared with obstetricians. Several other clinical factors warrant further investigation, including pelvic floor muscle training, immersion in water, antenatal perineal stretching using a massaging device (Epi-No), and the use of perineal ice packs in the second stage, particularly where oedema is present (Box 27.2 overleaf).

Care that reduces perineal trauma and/or improves maternal second-stage comfort

Recommendations

• Teach digital antenatal perineal massage in the last six weeks of pregnancy

• Warm packs do not reduce perineal trauma but improve maternal comfort during the second stage

• Giving birth in an upright (especially kneeling/all fours) or lateral position leads to increased maternal comfort during the second stage and to lower rates of episiotomy

• Women should be advised to follow their own urges to push during the second stage

• Some control of the baby’s head during birth is likely to be beneficial

• Vacuum extractors should be used in preference to forceps, as it leads to less maternal trauma

• Women should have support (constant caring companion) throughout labour and birth

• Giving birth in a home-like environment, such as a birth centre, is protective for perineal damage

• Giving birth at home leads to the lowest rates of perineal damage

• Giving birth with midwives compared with obstetricians is associated with a reduced use of episiotomy

Care that appears promising but needs further research in order to determine effect on perineal trauma and/or maternal second-stage comfort

Care that should be abandoned in light of the evidence that it does not reduce perineal trauma and/or improve maternal second-stage comfort

Recommendations

• Avoid intrapartum perineal massage

• There is no evidence that lidocaine spray reduces perineal pain during the second stage of labour

• Episiotomy should be avoided unless there are compelling reasons, such as severe fetal distress

• Women should be informed of the greater risk of instrumental birth associated with epidural usage and the associated perineal trauma risk

(Source: Dahlen 2007b)

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The pelvic floor

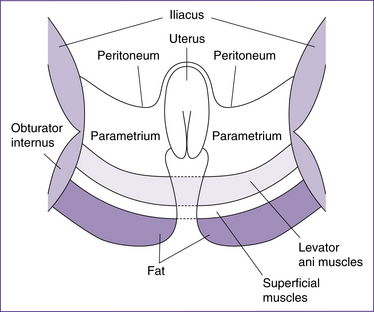

The pelvic floor is made up of soft tissue that fills the bony outlet of the bony pelvis. It essentially forms a sling and extends from the skin of the vulva, perineum and buttocks below to the pelvic peritoneum above. The layers from the inside out include (Fig 27.1):

• pelvic fascia, which thicken to form the supporting ligaments of the pelvic organs

• deep perineal muscles (levator ani)

• superficial perineal muscles

The main functions of the pelvic floor are to:

• support the pelvic organs (vagina, uterus, ovaries, bladder and rectum)

• maintain intra-abdominal pressure during coughing, sneezing, vomiting and laughing

• aid defecation and micturation

Pelvic fascia

The pelvic fascia consists of connective tissue that lines the pelvic walls and fills the spaces between the pelvic organs, and forms strong ligaments to support the uterus. It extends from the pelvic peritoneum and abdominal muscles above to the levator ani below.

The main supporting ligaments are:

• Broad ligaments, formed from the peritoneal covering of the uterine tubes; unlike the other ligaments, they do not have a supportive function.

• Transverse cervical ligaments (also known as the Cardinal or Mackenrodt’s ligaments), which arise from the vaginal vault and the sides of the cervix and extend laterally in a fan-like structure to be inserted into the white line of fascia on the lateral pelvic walls. These form the main support for the uterus.

• Uterosacral ligaments, which are attached to the upper portion of the posterior wall of the cervix and extend upwards and back, encircling the rectum before attaching to the front of the second sacral vertebrae (sacrum). Their main role is to support the uterus but also to keep it in its normal anteverted (forward-tilted) position.

• Pubocervical ligaments, fairly weak ligaments which originate in the cervix, pass under the bladder and attach to the pubic bone. They mainly provide support and stability for the bladder.

• Round ligaments, two bands of fibrous tissue enclosed in the peritoneum that originate near the fundus of the uterus. They pass between the folds of the broad ligaments to the sides of the pelvis, through the inguinal canal and fuse with the labia majora. Their function is to maintain the uterus in the anteflexed (bent-on-itself) and anteverted (forward-tilted) positions (Kettle 2005a).

Deep muscle layer

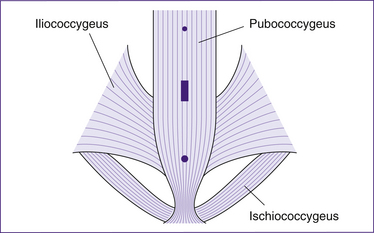

The deep muscle layer is around 3–5 cm in depth and is formed from a group of muscles known collectively as the levator ani. Each of these levator ani muscles arises from the internal lateral pelvic wall, the posterior aspect of the pubic bone, the white line of fascia and the ischial spine, to converge midline. They pass backwards and downwards to meet in the upper vagina, perineal body, anal canal and the lateral border of the coccyx and lower part of the sacrum (Kettle 2005a). This anatomical structure provides the hammock of strong muscle that supports the vaginal walls and uterus. The levator ani muscles also provide some support to the bladder and anal canal and counteract any increase in abdominal pressure. They are critical to the maintenance of the integrity and strength of the pelvic floor. They are divided into three main muscle groups (Fig 27.2): the pubococcygeus and puborectalis muscles in the levator ani, the iliococcygeus muscles and the ischiococcygeus muscles.

• The pubococcygeus muscles are the most important part of the levator ani, both in their size and function (Kettle 2005a). Their main function is to provide support to the urethra, vagina and rectum as well as aiding micturation, defecation and constriction of the vagina during sexual intercourse. The pubococcygeus muscles form the anterior section of the levator ani. They originate from the anterior part of the obturator fascia and sweep backwards to form U-shaped structures around the urethra, vagina and anorectal junction. The muscle fibres pass downwards and backwards below the bladder on either side of the urethra, upper vagina and anal canal posteriorly, and then are inserted into the anococcygeal body coccyx (Kettle 2005a).

• The puborectalis muscles form the most medial portion of the levator ani muscle and mark the transition from rectum to anus. They arise from the lower part of the symphisis pubis and converge with muscle fibres of the opposite side around the lower portion of the rectum. The strong sling that is thus formed helps to maintain the forward angulation of the anorectal junction and plays a part in maintaining continence of faeces (Kettle 2005a).

• The iliococcygeus muscles arise from the white line of pelvic fascia, and pass downwards and inwards to the anococcygeal body and coccyx. These muscles help to elevate the pelvic floor and are capable of rapid contraction.

• The ischiococcygeus muscles originate at the ischial spine and pass downwards and inwards to be inserted into the coccyx and lower sacrum. These muscles help to stabilise the sacroiliac and sacrococcygeal joints of the pelvis.

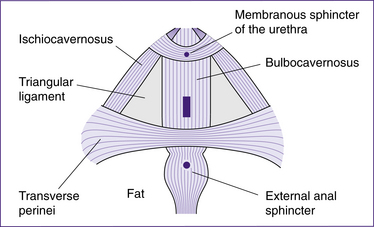

Superficial muscle layer

Although these muscles are small and contained in the superficial layer of the pelvic floor, they are critical to the overall function and strength of the pelvic floor. These muscles extend from the perineal body around the vagina to the clitoris (Fig 27.3). They strengthen the sphincter action of the vagina and urethra, and play a part in sexual function (Kettle 2005a). They are also the main muscles involved in perineal trauma.

• The bulbocavernosus muscles (also known as the bulbospongiosus) arise in the centre of the perineum, encircling the urethra and vagina, before inserting into the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris. Their main purpose is to constrict the vaginal orifice and contribute anteriorly to the erection of the clitoris in sexual activity.

• The ischiocavernosus muscles are situated in the lateral boundary of the perineum; they originate in the ischial tuberosities and terminate in the clitoris. Some of the fibres interweave with the membranous sphincter of the urethra. Their main function is to maintain the engorgement of the clitoris.

• The superficial transverse perinei are muscles that pass from the ischial tuberosities to the perineal body and join with the bulbocavernosus in front. Their main function is to support the lower part of the vagina and fix the central tendinous point of the perineal body.

• Deep transverse perinei are thin muscles that pass from each ischiopubic ramus to converge midline in the perineal body. Some of the fibres are inserted into the vagina and they contribute to stabilising the perineal body.

• The external anal sphincter muscle encompasses the anal opening and passes in front of the perineal body before attaching posteriorly to the coccyx. It controls the passage of faeces and flatus.

• The membranous sphincter of the urethra comprises two bands of muscle that originate at one of the pubic bones, passing above and below the urethra before inserting into the other pubic bone. It is capable of contracting to occlude the urethra (Kettle 2005a).

The perineal body

The perineal body is a fibromuscular structure situated between the lowest third of the vagina in front, the anal canal behind and the ischial tuberosities laterally (Kettle 2005a) (Fig 27.4). The perineal body is like a pyramid structure (approximately 3.5 cm in length), with the base of the pyramid being the skin. It is interlaced with the pubococcygeus, bulbocavernosus, superficial transverse perinei and external anal sphincter muscles. The lower part of the perineal body, where most of the superficial perineal muscles converge, is known as the central point

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree