16. Patients requiring upper gastrointestinal surgery

Melanie Seymour

(with a contribution by Nuala Davison)

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Overview of the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system302

Investigations302

Upper gastrointestinal disorders304

Bariatric surgery (Nuala Davison)319

At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to:

• describe the basic anatomy and physiology of the upper gastrointestinal system

• briefly explain specific investigations

• briefly explain causes, conditions and surgical interventions

• give examples of assessment procedures for patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal surgery

• highlight specific pre- and postoperative management

• give a case study example and evidence-based care planning

• assist in the education and discharge planning of patients.

Introduction

This chapter will provide information for nurses who are caring for patients on a surgical ward that specializes in upper gastrointestinal surgery. It will focus on surgical interventions that are carried out when all other methods of treatment have been ineffective, or are indeed inappropriate. This chapter will also include endoscopic practice, and both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures will be outlined.

It must also be remembered that there are many different techniques and practices in the field of gastroenterology. Therefore, surgical procedures may have slightly different names, according to their origin. It is important to use this book in conjunction with current evidence-based practice and research.

Each organ will be addressed in distinct sections of this chapter, and the associated anatomy and physiology will be discussed, followed by details of specific nursing assessment. However, the specific investigations will be addressed together at the beginning of the chapter in order to avoid repetition.

Nursing assessment refers to the collecting of data, reviewing or analysing the data, and identifying problems. It is essential that a comprehensive history is taken from the patient or their family to serve as a baseline for assessment. Assessment can be completed through interviewing, i.e. asking questions related to the patient’s condition, observation for any non-verbal indications of discomfort or distress, and measuring through use of tools of assessment, e.g. pain assessment chart. It is a continuous process and needs to be frequently reviewed. For the purpose of this chapter the framework is based on the Roper, Logan and Tierney model of nursing, as described in Holland et al (2004) and Holloway’s (1993) care planning, as this remains best practice in the ward environment. The generalized pre- and postoperative management remains the same as for any patient undergoing upper abdominal surgery, and only specific problems will be highlighted following the discussion of the disease or organ dysfunction.

Overview of the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system

The digestive system refers to the organs, structures and complementary glands of the digestive canal that together are involved in the breaking down of food constituents into smaller components for absorption and final utilization by the cells. The digestive system, therefore, consists of the gastrointestinal tract, which is a continuous musculomembranous tube lined with mucous membrane, which is approximately 9 m long. This tube extends continuously through the body cavity from the mouth to the anus, and includes the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus.

There are four basic activities that take place in the digestive system:

• ingestion – taking the food into the body (eating)

• peristalsis – movement of the food along the gastrointestinal tract

• absorption of nutrients into the cells for use

• defecation – the elimination of waste products.

Two methods of digestion are employed: chemical and mechanical digestion. Chemical digestion is where large carbohydrates, proteins and lipid substances are broken down by chemical reactions. Ancillary organs which produce and store digestive enzymes are involved in this process. These include the salivary glands, liver, gall bladder and pancreas, and are external to the digestive tract. Mechanical digestion is where the food is physically moved – e.g. chewing, and mixing or churning the contents in the stomach with the digestive enzymes.

Investigations

There are many investigative procedures that a patient may undergo in order to diagnose the disorder and enable the surgical team to plan the relevant course of action or surgical intervention (Table 16.1). It is often a process of elimination by considering differential diagnoses.

| Investigation | Surgery |

|---|---|

| Abdominal X-rays | GI tract/biliary tract |

| Fluoroscope | GI tract/biliary tract |

| CT scan | GI tract/biliary tract |

| Barium meal | Upper GI tract |

| Barium swallow | Upper GI tract |

| Cholecystogram | Biliary tract |

| Cholangiogram | Biliary tract |

| Cholangiography | Biliary tract |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) | Upper GI tract |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) | Biliary tract |

| Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) | Biliary tract |

| Ultrasound | GI tract/biliary tract |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | Upper GI tract |

The patient requires a full explanation of the proposed investigation, in order to make an informed decision about whether to go ahead with the test or not. Patients will be required to give verbal and, often, written consent. Informed consent will involve a discussion with the patient, outlining what the test will look at specifically, the risks involved, and the potential outcomes of the test and, indeed, not having the test at all. The Department of Health have an initiative called Good Practice in Consent which outlines the issues (DoH, 2001). The most common investigations are briefly described below.

Abdominal X-rays

Nursing issues

The most at-risk patients are therefore female patients of reproductive capacity, as there is an increased possibility of affecting a fetus through pelvic X-rays. Consequently, any abdominal radiography should be carefully monitored and only carried out if absolutely essential. A 10-day rule applies to all radiological examinations for female patients of reproductive age. This rule requires the examination to be carried out within 10 days following the first day of the last menstrual period. There may be some exceptions to this rule for those women who have been sterilized, are not menstruating or are not sexually active. Abdominal X-rays are useful in detecting gallstones (approximately 10% of gallstones are radio-opaque) and abdominal fluid levels.

CAT (computerized axial tomography) scan/CT scan

This provides a computerized picture of a part of the body, which is achieved by combining fine X-rays, often with a contrast medium. ‘Slices’ of the abdomen are produced and are useful for detecting irregular anatomy, including tumours.

Barium studies

A radio-opaque contrast medium called barium sulphate is used for radiological studies of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a fine, milky contrast medium that is taken orally, to allow detection of small alterations in the stomach.

Barium swallow and barium meal

This test is usually undertaken to highlight the oesophagus, stomach and upper intestinal tract, therefore assisting in detecting any exacerbation of oesophagitis, dysphagia, gastric or duodenal ulcers, or the presence of abnormalities such as hiatus hernia, strictures, obstruction or fistulae.

Nursing issues

It is advisable for the patient not to have anything to eat or drink for a period of 6–8 hours prior to the investigation, as the examination is more successful if the stomach is empty.

Cholecystogram

A cholecystogram is an X-ray showing the gall bladder following the introduction of a radio-opaque contrast medium containing iodine. This may be introduced by ingestion or injection, and the technique is usually undertaken to detect gallstones or biliary obstruction, or to assess the ability of the gall bladder to fill and empty. It has now been largely superseded by ultrasonography and other investigations.

Cholangiogram or cholangiography

The radio-opaque contrast medium is injected directly into the biliary tract or intravenously. The procedure is carried out during biliary surgery to detect any abnormalities or blockages, as it allows the bile ducts to be viewed on X-ray film. A cholangiogram can also be performed postoperatively in order to check the patency of the common bile duct following exploratory surgery and removal of any residual gallstones (sometimes the common bile duct can become oedematous and inflamed). The contrast medium is introduced through the indwelling T-tube inserted during the surgical procedure.

Nursing issues

The postoperative cholangiogram should be carried out and results reviewed by the surgical team prior to the removal of the T-tube. The nursing role will be discussed later in this chapter.

Endoscopy

The cavities or interior of the gastrointestinal tract can be investigated through the use of an endoscope, which is a luminous fibreoptic instrument that can be inserted through a natural orifice for viewing cavities and internal organs, then relaying them to a television screen. The fibreoptic endoscope is often used to reach areas previously inaccessible with other instruments, as it has greater flexibility. Instruments can also be passed through the special tube of the endoscope to obtain biopsies or perform other procedures such as polypectomy.

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

For examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract, it is necessary to wait for the stomach to be empty, for visualization and prevention of aspiration. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) is usually performed to detect and diagnose ulcers and tumours. It is also used to establish the cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and to obtain biopsy samples. It may also be referred to in the chapter as gastroscopy.

Nursing issues

It is necessary for the patient to have nothing orally for approximately 6 hours prior to these procedures, in order to ensure that the stomach is empty. During the procedure, an anaesthetic spray is often used to anaesthetize the throat. Therefore, following the procedure, it is usual to wait for throat sensation to return to normal prior to drinking. This takes approximately 1 hour, after which the patient may eat or drink normally. Sometimes, fluids are withheld following an oesophageal dilatation until X-rays have been taken, in order to rule out any damage or trauma caused by the procedure.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) views the biliary tree endoscopically. It can be purely diagnostic or also used for therapeutic purposes. The endoscope with a fine catheter is passed via the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum to the duodenal papilla. There, the pancreatic and common bile ducts are injected with the contrast medium introduced through the ampulla of Vater. Any irregularities will be viewed on the screen, and biopsies and cytology specimens may be taken. The investigation is usually performed to aid diagnosis of obstructive jaundice, chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma, or biliary colic, and can also facilitate the removal of gallstones.

Nursing issues

The patient should be nil by mouth for at least 6 hours prior to the procedure. An anaesthetic throat spray may be used, as may sedation. Following the procedure, the patient is usually unable to eat or drink for a few hours. Observations should include blood pressure and pulse for indications of bleeding or perforation. This procedure may be contraindicated in patients with cardiac and respiratory disorders (Hibberts and Barnes, 2003).

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

In percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), heavily concentrated contrast medium dye is injected straight into the biliary tree, enabling all parts of the biliary system to be viewed. This is done through a needle and catheter introduced transcutaneously under ultrasound guidance. It is particularly useful for investigating persistent symptoms related to the biliary system of those patients who have already undergone a cholecystectomy or gastrectomy and cannot have an ERCP.

Nursing issues

As in ERCP.

Ultrasound

High-frequency sound waves are transmitted by the ultrasound probe and echoes are received from various organs, outlining them. It is safe, as it is non-invasive, and does not use ionizing radiation. It is used in gastroenterology to investigate and detect abnormalities of the biliary system, pancreas, liver and spleen.

Nursing issues

If the ultrasound is carried out for investigation of the gall bladder or pancreas, it may be necessary for the patient to stop eating for up to 12 hours, and drink clear fluids only, prior to the procedure. This will ensure that the gall bladder will be fully enlarged due to the retention of bile.

Upper gastrointestinal disorders

Mouth

Anatomy and physiology

This chapter will not discuss disorders of the mouth but will highlight the importance of a healthy mouth in the role of digestion. The mouth contains structures that are involved in the preparation of food for passage through the gastrointestinal tract. These structures are the tongue, teeth, hard and soft palates, and salivary glands. The act of biting and chewing requires the ability of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue to move the food from side to side, and the intrinsic muscles of the tongue to alter the shape of the food for swallowing. This act of chewing is also variable according to the dental pattern and shape of the mouth of the individual and the type of food ingested.

The formation and assisted passage of the bolus requires the secretion of saliva from the parotid, submandibular and sublingual salivary glands, which secrete mucus and amylase. The flow of saliva is dependent on the stimulus initiated from taste and pressure in the mouth. Saliva is also responsible for keeping the mouth clean and removing food particles through keeping it moistened (Rutishauser, 1994).

It is therefore important that individuals have moistened, clean mouths and regular dental check-ups to assist and facilitate the function of chewing, forming and swallowing the bolus of food.

Oesophagus

Anatomy and physiology

The oesophagus, sometimes called the gullet, is approximately 24 cm long, and is a muscular canal which is collapsible. It runs from the base of the pharynx, behind the trachea, through the opening between the thoracic cavity and abdominal cavity, terminating at the lower oesophageal sphincter of the stomach. It comprises four layers:

• The tunica adventitia (outer layer).

• The muscularis – longitudinal and circular muscles that aid propulsion of food via the action of peristalsis. These muscles graduate from voluntary or striated muscles at the upper, pharyngo-oesophageal sphincter to involuntary or smooth muscles at the cardiac sphincter.

• The submucosal layer, containing blood vessels and tissue.

• The mucosal layer, which aids passage of the food bolus along the oesophagus through the secretion of mucus from special glands.

The function of the oesophagus is to transport the food bolus along the canal by the involuntary action of peristalsis (contractions and waves). The whole process takes 1–8 seconds, depending on the consistency of the food bolus. The pharyngo-oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal sphincters control the flow of the bolus by relaxing, so as to allow the passage of the food through, and contracting, to prevent backflow of contents.

Oesophageal dysfunction

Dysfunction refers to any condition that disrupts or affects the normal function of the oesophagus, resulting in uncomfortable symptoms. Symptoms may include acute pain (odynophagia) and difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia), obstruction of food, and feeling the passage of liquids when swallowing, and often the patient will be able to point to the locality of the problem. Some of the conditions, causes and interventions are shown in Table 16.2 and are described below.

| Cause | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Oesophageal diverticulum | Oesophagomyotomy |

| Oesophageal trauma/perforation | Gastroscopy/oesophagogastroduodenoscopy/reconstructive surgery |

| Oesophageal achalasia | Oesophagomyotomy or dilatation |

| Oesophageal stricture | Dilatation, insertion of a stent |

| Oesophagitis | Dilatation, oesophagastrostomy, fundoplication, vagotomy and pyloroplasty |

| Oesophageal cancer | Oesophagectomy, insertion of a stent |

Oesophageal diverticulum

Oesophageal diverticulum refers to a weakness in the muscle wall of the oesophagus where a pouch of mucosa and submucosa can slip through, causing a protrusion. Diagnosis is through barium swallow and X-rays. Gastroscopy or passing of a nasogastric tube is not undertaken, as there is an increased risk of perforation.

Intervention

Intervention is by removal of the pouch surgically. Because of its position, care must be taken to avoid damaging the adjacent vessels, and often a myotomy (a cut in the muscle) is performed to reduce the risk of spasticity to the muscle.

Oesophageal trauma and/or perforation

External trauma can be caused by stab, bullet or crush wounds. Internal trauma can be caused by swallowing foreign bodies, puncture from sharp objects or following an investigative procedure. Examples of these are metallic objects, dentures, fish bones and medical instruments. Other trauma effects can be through the ingestion of poisonous substances, or continuous unrelieved strain caused by vomiting, resulting in mucosal trauma (Mallory–Weiss tear) or full-thickness rupture of the oesophagus.

Intervention

Oesophagoscopy is commonly undertaken with removal of the foreign body or dilatation. In severely traumatized cases, a gastrostomy is created for the insertion of a feeding tube to allow the traumatized area of the oesophagus and oedema to subside. Antibiotics may be prescribed following a perforated oesophagus, as there is an increased risk of infection.

Oesophageal achalasia

Oesophageal achalasia is a neuromuscular change that causes benign spasm of the lower oesophageal sphincter, sometimes with marked dilatation of the oesophagus. The lower oesophageal sphincter fails to respond and relax in order to facilitate swallowing. This results in the patient feeling that food is stuck in the gullet. Food is often regurgitated, and oesophageal distension occurs. There is a danger of spillover of food from the oesophagus into the trachea, causing respiratory aspiration. Diagnosis is through OGD and barium swallow.

Intervention

The aim would be to dilate the lower oesophageal sphincter using a balloon under pressure, inserted under X-ray or endoscopic guidance. There is a risk of perforation in a small percentage of the procedures. A surgical oesophagomyotomy, i.e. division of the muscle wall, may be performed if dilatation fails.

Oesophageal varices

Oesophageal varices are enlarged, swollen, engorged vessels at the base of the oesophagus that are at risk of rupturing, causing a torrential haemorrhage, which can be life threatening.

Intervention

The aim of treatment is to stop the haemorrhage. This is done endoscopically by injecting the varices with adrenaline (epinephrine), or by placing a band around the bleeding vessel. In an emergency situation a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube is inserted to block the gastro-oesophageal junction to stop bleeding.

Oesophageal stricture

Oesophageal stricture may be caused by intensive and prolonged radiotherapy; through external pressure on the oesophagus by an enlarged adjacent organ or tumour; cancer of the oesophagus; or ingestion of caustic substances. The commonest cause of oesophageal stricture, however, is an inflammatory stricture caused by acid reflux (see below). Diagnosis involves a specific comprehensive history of any recent changes in swallowing, and investigations include endoscopy and biopsy.

Intervention

Intervention is by treatment of the underlying cause and may include dilatation of the lumen of the oesophagus and possibly the insertion of a stent.

Oesophagitis

The mucosal lining of the oesophagus becomes inflamed following an acute or chronic episode of infection, e.g. fungal; irritation, which includes malignancy, chemical ingestion or prolonged use of a nasogastric tube; complications following gastric/duodenal surgery; or trauma, caused by repeated vomiting, reflux, bending, coughing, stooping or straining. Investigations include a specific history, oesophagoscopy and/or biopsy (Day, 2003).

Intervention

Intervention is by treatment of the underlying cause and may involve medical treatment or dilatation, oesophagastrostomy, fundoplication, vagotomy and pyloroplasty.

Oesophageal cancer

This is the ninth most common type of cancer in the UK, with nearly 7200 new cases each year. Approximately 5% of the total cancer deaths in the UK are caused by oesophageal cancer (Cancer Research UK, 2008a). It is more common in people over the age of 60, and is twice as common in men as in women. The 5-year survival rate is 7% in men and 8% in women.

There are two main types of oesophageal carcinoma.

• Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for half of the diagnosed cases, and develops in the squamous cells which form the lining of the oesophagus.

• Adenocarcinoma begins in the gland cells that make the mucus in the lining of the oesophagus, and is usually found in the lower third of the oesophagus. It may infiltrate adjacent structures up and down the oesophagus, is insidious in its onset and does not cause symptoms in the early stages. Symptoms may include involvement of the vocal cords, i.e. hoarseness, dysphagia leading to total blockage in some cases, anorexia with weight loss, pain, regurgitation of undigested food, persistent cough or clearing of the throat, halitosis or foul-smelling breath and haemoptysis. The tumour may eventually invade other adjacent structures, such as the bronchi, trachea, pericardium and great blood vessels, with metastases in the lymph nodes and liver. A patient with Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition where the lower oesophagus has ulcerative benign lesions in the columnar epithelium, is 50 times more likely to get this type of cancer. It is therefore important that the individual undergoes regular gastroscopy surveillance.

Oesphageal carcinomas are thought to be associated with an increased consumption of alcohol, tobacco, hiatus hernia and Plummer–Vinson syndrome (i.e. cricoid webs causing dysphagia and achalasia). There may be a decreased incidence if an adequate intake of vitamins A and C and the mineral zinc are included in the diet.

Investigations

Investigations include a specific history as outlined in assessment, barium swallow, OGD, biopsy, endoscopic ultrasound and CAT scan. A bronchoscopy may also be performed to rule out any tracheal involvement.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound has revolutionized the staging of oesophageal cancers. The patient undergoes a gastroscopy, but a fibreoptic tube with an ultrasound crystal is inserted, instead of the camera. The tumour can then be sized, its relation to adjacent structures established and involvement of lymph nodes assessed.

Intervention

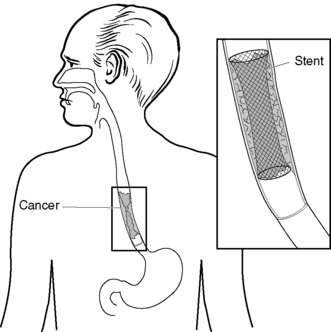

Surgical intervention is undertaken if the tumour is considered curative, i.e. partial or total oesophagectomy, or palliative intervention may include the insertion of a self-expanding metallic stent. Treatment may also involve chemotherapy, or laser treatment (photodynamic therapy or PDT). Radiotherapy may be effective with an early-stage carcinoma, or as a palliative measure in the advanced stages. If the patient is severely dysphagic, a feeding jejunostomy may be created to meet nutritional needs.

Insertion of a stent

When the carcinoma is severely advanced or involves adjacent organs and tissues, palliative intervention may be the option of choice. An expanding stent is passed to ensure that the oesophagus remains patent (Fig. 16.1), thus allowing a soft diet to be taken enterally by the patient (Bailey, 2004).

|

| Figure 16.1 • Oesophageal stent. |

Surgical intervention

Surgical intervention is by an oesophagectomy, where part or all of the oesophagus is removed. The surgical approach may be through the thorax and abdomen, abdomen alone or thorax alone, leaving the stomach positioned in the thoracic cavity. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy can also be used in conjunction with an oesophagectomy, either prior to or following surgical intervention.

Oesophageal surgery – specific preoperative assessment

Eating and drinking is clearly one of the problems for a patient undergoing an oesophagectomy, and should be discussed in detail as part of the specific preoperative assessment. Questions should be asked and documented in relation to the specific history, to identify changes in appetite, increasing dysphagia, substernal pain, regurgitation, vomiting, severe weight loss, increased anxiety, metastatic gland enlargement in the neck, haematemesis and, finally, melaena or anaemia. Examples of questions are: ‘How long have you had difficulty in swallowing?’ ‘Does it affect all foods or just fluids?’ ‘Do you regurgitate the food?’ ‘How long does it take you to swallow the food?’ ‘Where does the food stick?’ ‘Does it cause pain?’ ‘If so, whereabouts?’ ‘Is it getting worse or better?’ As a result of the appropriate questions being asked, specific problems are identified, as shown in Box 16.1.

Box 16.1

Box 16.1 Specific issues related to eating and drinking

• Nutritional deficit – due to alteration in appetite as a result of nausea, anorexia, regurgitation, dysphagia or pain on ingesting food.

• Increased weight loss – following alteration in appetite/pathology.

• Potential risk of malnutrition – following decrease in nutritional status/pathology.

Specific objective will be to ensure that adequate nutritional levels are maintained and that the patient is well nourished prior to surgical intervention. Any associated pain and discomfort is relieved or removed.

Nursing intervention and rationale

• Assess the ability of the patient to retain food and fluids. Document food, calorie and fluid intake on the appropriate charts along with weight charts. This will help to monitor nutritional intake and any weight fluctuation, and identify need for further intervention.

• Facilitate passage of food by offering drinks along with food intake; sometimes, soda water will help to clear the blockage and dislodge any food that is trapped. Small, frequent, light meals should be offered that are easy to swallow. All meals should be offered in a conducive environment.

• It may be necessary to give liquidized nutritional intake with vitamin supplements and high-protein fluid drinks, or totally replace enteral nutritional intake with parenteral feeding in order to provide the nutritional requirements.

• It is advisable to involve the dietitian and/or the nutritional specialist nurse to provide additional educational input, thus preventing further complications or problems following the introduction of special diets.

• Initialize appropriate referral to dietitian and possibly gastroenterologists.

• Maintain food chart/nutritional documentation to monitor patients’ requirements.

Specific postoperative nursing interventions

Maintaining a safe environment

Immediate assessment is made of the patient’s airway, colour, oxygen saturation levels, vital signs and level of consciousness, to prevent further complications arising of hypovolaemic shock, postoperative atelectasis and unrelieved pain.

Breathing

Specific postoperative assessment should consider the respiratory needs and possible management of a closed chest drain. This drainage system is positioned in the pleural cavity and may or may not be on suction to ensure that the lungs remain inflated. The water should be deep enough to cover the drainage tube in the drainage bottle and has the function of acting as a valve to prevent air from re-entering the pleural cavity. Circulatory needs require the monitoring of vital signs to identify if the patient is at risk of hypovolaemic shock. Encourage movement by passive and active exercises to prevent thromboembolic complications.

Eating and drinking

It is important that postoperative nutritional and fluid needs are met by a regimen of fluid replacement and volume expanders intravenously, including total parenteral nutritional (TPN) replacement and/or supplements. Often, a jejunostomy tube is inserted at operation for postoperative feeding, before the patient is allowed to ingest food some days later when the anastomosis has healed.

Personal cleansing and dressing

There is a high risk of wound infection. Therefore, careful monitoring of the wound for signs of clinical infection, i.e. redness, swelling, heat, pain and exudate, should be undertaken. Comfort needs include assistance with hygiene and creating a safe environment.

Elimination

Monitor for urinary retention, which is related to the neuroendocrine response to stress, anaesthesia and recumbent position.

Additional specific potential complications

These complications include anastomotic leakage, malnutrition, pneumothorax, aspiration pneumonia, wound infection, blocked stent, fistula development, poor prognosis and associated high levels of anxiety.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access