12. Patients requiring surgery to the ear, nose and throat

Julie Wain

The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of ear, nose and throat, head and neck surgery for nurses. At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to:

• describe the anatomy and physiology of the ear, nose and throat

• describe ear, nose and throat conditions that require surgery

• demonstrate knowledge of nursing assessments specific to this specialty

• discuss pre- and postoperative nursing care

• provide professional and caring patient education, including safe discharge planning

• be familiar with the terminology related to rhinology, otology and laryngology.

Introduction

The 19th century saw the establishment of ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery as an independent specialty. Throughout the 20th century, major advances were made: the development of microscopic, endoscopic and laser techniques; day case surgery; and innovative approaches shown in reconstructive head and neck surgery. These have had a great impact on nurses working within an ENT unit. Surgery can be a less traumatic experience for the individual, recovery can be faster, and patient turnover is greater. In day surgical units, ENT surgery is now being performed on individuals who, having fulfilled certain criteria (as discussed in Ch. 3), are able to undergo general anaesthetic procedures and suffer only minimal disruption to their daily lives. The multidisciplinary ear, nose and throat, head and neck team can now offer a more optimistic future and improved quality of life for those patients suffering from extensive and malignant disease of the head and neck.

The diversity within ENT surgery provides nurses working on an ENT ward with a wealth of opportunities and experience from which nursing skills and competencies can develop. It is hoped that the reader, upon following this chapter, will experience the rewards and challenges of otorhinolaryngology nursing care.

The ear

Anatomy and physiology

The ear is divided into three parts:

• the external ear

• the middle ear

• the inner ear.

The external ear

The pinna, composed of fibroelastic cartilage and skin, acts by localizing and amplifying sound and protecting the auditory canal from the environment and from trauma. This canal efficiently self-cleans by the continuous migration of epithelium from the inner to the outer aspect of its structure. Sound waves travel down the canal to the tympanic membrane, which transmits sound vibrations into the middle ear.

The middle ear

This is an air-containing cavity. It connects with the nasopharynx via the eustachian tube, which ventilates and equalizes pressure within the cavity. The middle ear contains three ear ossicles: the malleus, incus and stapes. These transmit sound vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea of the inner ear. Posterior to the middle ear lie mastoid air cells. The mastoid process is closely related to the cerebellum, temporal lobe and the labyrinth of the inner ear. Portions of the facial nerve, which innervates facial movements, and the chorda tympani nerve, responsible for taste perception, are also located here (Waddington et al, 1997).

The inner ear

The inner ear consists of two sections: the cochlea (hearing canal) and the vestibular apparatus (balance canal), contained within the labyrinth (Dart, 1997). Endolymph circulates in both canals to transmit sound and balance signals. The vestibularcochlear nerve has two branches and functions: the cochlear/auditory nerve for transmission of electrical impulses to the cerebral cortex, where sound is perceived; and the vestibular nerve, which transmits impulses from the inner ear and semicircular canals to the cerebellum, processing information regarding posture, movement and balance.

Conditions of the ear that require surgery

There are a variety of conditions and diseases that benefit from surgical intervention. The following details the main examples, with types of surgery explained in Box 12.1.

Box 12.2

Box 12.2

• Exostoses: an overgrowth of bone in the external auditory canal. Repair is by canaloplasty.

• Ossicular discontinuity: ossiculoplasty aims to repair the ossicular chain.

• Otosclerosis: an overgrowth of bone causing fixation of the stapes footplate and conductive deafness. This condition is familial, more common in women, and one which pregnancy appears to exacerbate. Repair is by stapedectomy.

• Acoustic neuroma (schwannoma): a tumour of the vestibular element of the eighth cranial nerve. Its incidence is rare and progress can be slow; neurosurgeons and otologists often perform the surgery collaboratively.

• Cholesteatoma: a benign growth of squamous epithelial cells in the middle ear and mastoid air cells, which may lead to infection and suppuration, conductive and sensorineural hearing loss and facial nerve paralysis. Unless adequately treated, bony involvement (mastoiditis) occurs, which can lead to extra- and intracranial complications (Box 12.2). Surgery to remove cholesteatoma is mastoidectomy.

Box 12.2

Box 12.2 Potential progression of severe middle ear infection

Otologic complications

• Perforated tympanic membrane

• Mastoiditis

• Mastoid abscess

• Labyrinthitis

Head and neck complications

• Neck abscess

• Facial nerve palsy

Cerebral complications

• Extradural abscess

• Meningitis

• Subdural abscess

• Cerebral abscess

• Ménière’s disease: aetiology is unknown. It affects the inner ear, causing vertigo, tinnitus and deafness. Endolymphatic sac decompression is occasionally performed, but a variety of medical treatments are first explored. No one treatment suits all Ménière sufferers. Labyrinthectomy is performed if symptoms are severe and causing continued distress to the patient.

• Profound sensorineural deafness: may benefit from a cochlear implant.

• Deafness: a variety of deaf patients benefit from a bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA) – a permanently implanted hearing aid.

Box 12.1

Box 12.1 Types of ear surgery

• Myringoplasty: this is closure of a tympanic membrane perforation using a graft of temporalis fascia. The graft is tucked into place behind the membrane and is gently supported by pieces of Gelfoam, which are gradually absorbed over a few weeks. The graft is not completely stable until about 6 months later. There are two types of approach: endaural and postauricular. This procedure is also known as type I tympanoplasty.

• Ossiculoplasty: a connection is made between the stapes and malleus in order to improve ossicular conduction of sound. A myringoplasty may also be performed at the same time. This procedure is also known as type II tympanoplasty.

• Mastoidectomy: there are three types. A postauricular approach is used.

– Cortical: mastoid air cells are removed; hearing is unaffected.

– Radical: more extensive than cortical; the eardrum, bony ear canal wall, middle ear mucosa and ossicles are removed; hearing is greatly affected.

– Modified radical: preserves as much of the eardrum and ossicles as possible; hearing is less affected.

• Stapedectomy: a window in the footplate of the stapes is made, and the diseased stapes is removed. A prosthesis is inserted which is mobile, to allow for the vibration and conduction of sound.

• Saccus decompression: the endolymph that fills the membranous labyrinth of the inner ear is drained, in order to alleviate vestibular disturbance.

• Labyrinthectomy: the entire structure of the labyrinth in the inner ear is destroyed, resulting in total hearing loss on that side.

Specific investigations

By a process of air conduction, sound waves pass through the ear canal to the ossicular chain. Bone conduction enables wave transmission to reach the inner ear, where sound energy is transformed into neural energy and interpreted by the brain. If a problem is identified within the external or middle ear, any hearing loss is termed conductive. If there is a cochlear, auditory nerve or central nervous system problem, hearing loss is sensorineural. Box 12.3 lists causes of specific hearing loss.

Box 12.3

Box 12.3 Causes of specific hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss

• Impacted wax

• Foreign body in ear canal

• Damage to tympanic membrane

• Otosclerosis

• Cholesteatoma

Sensorineural hearing loss

• Arteriosclerosis

• Congenital

• Ototoxic drugs

• Acoustic neuroma

• Trauma from ear/head injury

• Overexposure to high-intensity noise

• Presbycusis

Clinical tests of hearing and ear disease

• Simple audiometry: i.e. use of tuning forks (Rinne and Weber tests): these distinguish between conductive and sensorineural loss. It is inexpensive, simple and portable.

• Auriscopy: an examination of the inner aspect of the ear canal and tympanic membrane, to visualize and diagnose conditions such as wax (cerumen) accumulation, perforation, foreign body, otitis externa/media, exostosis, cholesteatoma and mastoiditis.

• Pure tone audiometry: a formal measurement of hearing, usually conducted by an audiologist. The patient wears earphones and signals when a sound is heard. Results are plotted on graphs, reflecting air conduction and bone conduction of sound.

• Impedance audiometry: gives information about middle ear pressure, eustachian tube function and middle ear reflexes, and can provide measurement of any facial nerve dysfunction (Black, 1997).

• Speech audiometry: determines speech reception threshold and discrimination, and is effective in diagnosing sensorineural loss and evaluating for hearing aids.

• Vestibulometry: determines the functional state of the vestibular system; is useful in diagnosing dizziness.

• Otoacoustic emissions: assesses hearing in newborns to determine whether the cochlea is functioning. A probe with a speaker and a microphone is inserted into the ear canal. Tones are sent from the speaker through the middle ear, stimulating the hairs in the cochlea. The hairs respond by generating their own minute sounds, which are detected by the microphone. If there is a hearing loss, the hairs in the cochlea do not generate sound.

• Brainstem auditory evoked responses: measures the timing of electrical waves from the brainstem in response to clicks in the ear. Delays of one side relative to the other suggest a lesion in the eighth cranial nerve (such as acoustic neuroma), between the ear and brainstem, or the brainstem itself.

• Radiology: X-rays are useful to indicate stages of disease. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are excellent diagnostic tools, particularly in determining middle ear and mastoid disease and acoustic neuroma.

• Clinical test of balance: the Romberg test is used to determine if a lesion is cerebellar or labyrinthine in origin. With feet together, the patient closes their eyes, standing erect. A labyrinthine lesion can cause the patient to sway to the side of the lesion, which is accentuated by closing the eyes. A cerebellar lesion may show symmetrical swaying unaffected by eye closure.

• Clinical test of gait: the patient walks in a straight line between two points and then quickly turns to return on the straight line. Patients with a labyrinthine lesion deviate to the side of the lesion. Marked imbalance on turning indicates a cerebellar lesion.

• Clinical test of facial nerve: the facial nerve is the main motor nerve to the facial muscles and the stapedius muscle in the middle ear, and enables taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Facial nerve function in ear disease should always be assessed.

In relation to hearing loss, the presence of any otalgia (earache), otorrhoea (aural discharge) and tinnitus also aids diagnosis. Observing for nystagmus is also important; the eye moves slowly away from the affected side and then rapidly flicks back (horizontal nystagmus). This is common in inner ear disease.

Nursing assessment of a patient requiring ear surgery

On admission, the nurse gains a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s physical and psychological status. A model of nursing such as that of Roper, Logan and Tierney (2000) provides the framework for this. Specific to a patient requiring surgery to the ear and the subsequent postoperative care is the assessment of the following activities of daily living: communicating; working and playing; expressing health body image; eating and drinking; and eliminating.

Communicating

Hearing loss is a major disability that affects one’s social, work and educational life. The nurse needs to assess the patient’s hearing loss by addressing the following issues.

• Location and nature:

– Which side is affected?

– How severe is the loss?

– Is there distortion of sound or tinnitus?

• Effects of the hearing loss:

– on socializing

– at work or study

– with routine activities, e.g. shopping, telephoning

– on body image and self-esteem.

The nurse should endeavour to provide the optimum environment for effective two-way communication (Box 12.4).

Box 12.4

Box 12.4 Nursing skills of communication for patients with impaired hearing

• Ensure a well-lit area to facilitate lip-reading and observation of facial expression.

• Ensure the patient’s attention.

• Face the patient.

• Speak in a normal tone; shouting can cause distortion of sound.

• Speak clearly.

• Rephrase if misunderstood or misheard.

• Approach the better ear if not heard, but not too closely.

• Do not cover your face or lips, or speak with anything in your mouth.

• Write down anything that is not well understood.

• Do not rush the conversation or show annoyance or frustration; patients with hearing loss are often sensitive to facial expression.

• Encourage the use of the patient’s hearing aid and give time for the patient to adjust it.

• Involve the patient in doctors’ rounds; ensure all members of the multidisciplinary team are aware of the hearing loss; avoid talking over the patient, and check for understanding.

Encouraging the expression of any fears or concerns about surgery and aftercare is essential. Some types of surgery, e.g. stapedectomy and mastoidectomy, carry some degree of risk to that side of further, or even total, hearing loss.

Working and playing

Establishing the patient’s occupation and social situation helps the nurse to assess care and plan safe discharge. Some occupations involve exposure to high levels of noise, e.g. builders or musicians, and this may have contributed to, or caused, the hearing loss. The surgeon may recommend changing occupation.

A certain amount of time (1–2 weeks) for full recovery is required in order to avoid complications. Arrangements will need to be made in advance for time off work and the caring of dependants, if maximum rest is to be achieved. Home and work life needs must be addressed preoperatively.

Body image

Body image and self-esteem can suffer if hearing loss interferes with the patient’s life. Patients can feel sensitive, embarrassed, shy, and many lead isolated lives.

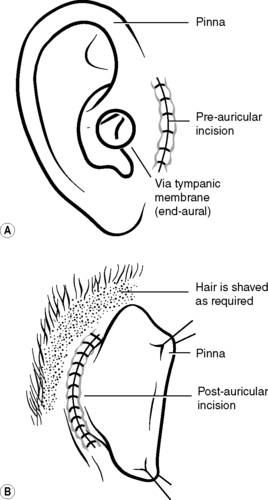

Scarring from surgery is minimal; incisions are either pre-auricular, via the tympanic membrane, or post-auricular (Fig. 12.1). The latter may involve shaving of hair, and this may cause the patient some concern.

|

| Figure 12.1 • Types of incision in ear surgery. |

Eating and drinking

Assessing the patient’s normal diet and appetite is important. Due to labyrinth disturbance, postoperative complications may include dizziness, nausea and vomiting.

Case study

The following case study aims to demonstrate both pre- and postoperative care for an individual undergoing a stapedectomy for otosclerosis.

Mrs Susie Marsh is a 42-year-old housewife and mother of two children (aged 9 and 14 years old). Her husband, a businessman, works in France and returns home for weekends. Susie was electively admitted for a right-sided stapedectomy. Her symptoms include mild tinnitus and progressive right-sided hearing loss. Her two pregnancies may have exacerbated this loss.

Nursing assessment

Box 12.5 identifies the nursing assessment of Susie Marsh.

Box 12.5

Box 12.5 Preoperative nursing assessment of a patient undergoing a stapedectomy

Maintaining a safe environment

• Observation of vital signs is performed: pulse, 72 beats per minute; blood pressure, 110/65 mmHg.

• Allergies: none known.

• Past medical history: caesarean section 9 years ago under general anaesthetic.

• Medication: Fybogel™ (fibre) sachet as required to maintain bowel regularity.

• Susie is anxious about surgery, in particular the potential but minimal risk to her existing right-sided hearing. She also expresses concern about speed of recovery, as her mother is caring for her children and her husband is away in France until the weekend (5 days away).

Breathing

• Respiratory rate: 14 respirations per minute.

• Susie smokes 10–15 cigarettes per day.

• Chest X-ray: no abnormalities.

Controlling body temperature

• Susie’s temperature is 36.5°C.

Communicating

• Susie has normal vision.

• Normal hearing is present on the left side.

• Susie has pronounced right-sided hearing loss; mild tinnitus is present; she finds socializing difficult, particularly with large, noisy groups of people. It causes her some embarrassment; a hearing aid is not used.

• Susie expresses concern about surgery and home commitments.

Eating and drinking

• Susie is petite: height 1.55 m; weight 50 kg.

• Susie has a normal appetite and diet.

Eliminating

• Susie is prone to constipation; bowels open every 2–3 days.

• She takes Fybogel™ to maintain this activity.

• Susie passes urine normally; urinalysis shows no abnormalities.

Personal hygiene and dressing

• Susie bathes every night and showers after exercise.

Mobility

• Susie is independent.

• Right-sided hearing loss makes her more cautious when driving, or out-and-about and in crowds.

Working and playing

• Susie is a housewife and mother; her husband is only at home at weekends, so she leads a very busy home life.

• Susie swims twice per week and walks the dog every day.

• Susie expresses concern about the family’s summer holiday in 4 months’ time; they plan to fly to Spain.

Body image

• Susie is casual about her appearance and seems relaxed about the minimal expected surgical scarring.

Sleeping

• Susie sleeps well, about 7–8 hours per night.

Dying

• Susie feels a little apprehensive about the anaesthetic.

Specific preoperative preparation

The doctor admits and obtains informed consent from Susie. This includes a detailed discussion about any risks associated with surgery. The potential deterioration or total loss of hearing on her right side, due to failure of the prosthesis or surgical trauma, is of particular concern to Susie. The doctor seeks to allay such anxieties by providing realistic information and by confirming that Susie understands all aspects of the procedure.

Audiometry, unless performed within the previous 6 months, is repeated in order to obtain up-to-date information about Susie’s current hearing function.

Postoperative nursing care

Previous chapters have discussed general issues of postoperative care. For Susie, specific potential complications of surgery include displacement of the prosthesis, facial nerve palsy, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, and difficulties in communicating. Box 12.6 details the plan of nursing care and evaluation of care given.

Box 12.6

Box 12.6 Postoperative nursing care of a patient following a stapedectomy

Susie Marsh returns to the ward following a right-sided stapedectomy. She is orientated but drowsy. Oxygen therapy is in progress at 4 L/min. An intravenous infusion is in progress. Susie is allowed to take oral fluids if not nauseous. A cotton wool plug sits in the external ear canal and is covered by a light gauze dressing; it appears to be moderately bloodstained. The surgeon has instructed flat bedrest with one pillow until the following morning in order to maintain the integrity of the prosthesis.

Breathing

• Problem: Potential loss of clear airway and respiratory distress due to anaesthetic, drowsiness and flat bedrest.

• Goal: Susie maintains a clear airway and normal breathing.

• Care:

– Ensure oxygen is given at the prescribed rate; provide oral care to prevent a dry mouth.

– Encourage Susie to lie in the recovery position, with operated ear uppermost, until fully awake, to maintain optimum airway; one pillow is allowed for comfort.

– Frequently observe respiration rate, depth and rhythm (¼–½ hourly for first 2 hours, reducing to 1–2–4 hourly as condition stabilizes); also observe for cyanosis or respiratory difficulty and report at once to doctor.

– Encourage deep breathing and coughing to clear secretions.

• Evaluation: Though drowsy for the first 2 hours, Susie showed no signs of respiratory distress. Oxygen therapy was stopped after the prescribed 4 hours. Though a smoker, her chest remained clear. Respiratory rate: 12–16 rpm.

Maintaining a safe environment

• Problem: Potential disturbance of middle ear prosthesis due to its initial vulnerability.

• Goal: To maintain integrity of prosthesis.

• Care:

– Ensure Susie remains on flat bedrest as instructed; allow one pillow only.

– Ensure Susie does not fall out of bed as she will feel dizzy and drowsy for the first few hours.

– Place the call bell and necessities to hand, to minimize any inconvenience from the bedrest.

– Assist Susie in meeting her daily needs, but reduce physical activity to the minimum; ensure Susie knows not to move suddenly or jerkily; offer the slipper bedpan for toileting; facilitate taking of diet and fluids by providing soft foods and drinking straws.

– The following morning, ensure Susie mobilizes gently, at first with assistance in case of dizziness.

– Advise Susie not to perform highly strenuous activity for the next 6 months.

• Evaluation: Susie found flat bedrest tiresome but maintained it well despite a few episodes of nausea. She successfully used the slipper bedpan and took fluids easily with a straw. The next morning, Susie cautiously but safely mobilized. The doctors advised her to continue restful activity for the next 2 weeks and that flying to Spain in 4 months’ time was acceptable.

• Problem: Potential facial nerve palsy due to surgical trauma to the facial nerve.

• Goal: To promptly detect the onset of any facial nerve defect.

• Care:

– Perform facial nerve checks when taking vital signs: observe Susie’s face at rest for asymmetry; ask Susie to raise both eyebrows; ask Susie to smile; ask Susie to close both eyes tightly.

– If any weakness or deficit is noted, inform the doctor immediately and continue monitoring.

– Reassure Susie that any weakness is more than likely due to postoperative swelling causing nerve compression and that this tends to resolve completely.

• Evaluation: Regular checks were maintained and no weakness was noted. Therefore, facial nerve function remained intact.

Eating and drinking

• Problem: Susie feels unable to eat and drink normally because of postoperative dizziness, nausea and flat bedrest.

• Goal: To alleviate nausea, any vomiting and dizziness; for Susie to gain adequate hydration and return to a normal diet.

• Care:

– Administer intravenous infusion as prescribed and check patency and integrity of cannula and site.

– Maintain accurate fluid balance chart until intravenous infusion is complete and Susie is drinking normally.

– Administer antiemetic therapy as prescribed/required and monitor effect; encourage Susie to inform staff if feeling nauseous or dizzy, and also frequently ask her how she feels.

– Oral fluids/diet are encouraged once nausea has subsided; first offer clear fluids, then light bland foods; then encourage relatives/friends to bring in favourite food and drink.

• Evaluation: Susie felt dizzy and nauseous upon returning to the ward. An antiemetic was given as prescribed, with good effect, though mild dizziness persisted. Susie then took oral fluids but declined diet until morning. The intravenous infusion was discontinued after breakfast was eaten. Susie was discharged home later that afternoon, once breakfast and lunch had been eaten and tolerated. She felt ‘light-headed’, but her family were there to take her home.

Communicating

• Problem: Susie states the hearing on her right side is worse than before surgery; she is anxious, particularly upon noting the bloodstained dressing.

• Goal: To alleviate Susie’s anxiety.

• Care:

– Reassure Susie that deterioration in hearing is normal; surgical oedema, aural packing and any middle ear drainage impairs existing hearing; effects of surgery are often not known for 2–6 weeks.

– Some bleeding is expected; a moderate discharge of fresh blood onto the cotton wool can continue for the first 24 hours, and then this gradually declines.

– Promote effective communication skills (see Box 12.4).

• Evaluation: Once the probable reason for Susie’s worsened hearing was explained, she felt less anxious, and the postoperative visit by the surgeon was reassuring. Bleeding was moderate, and the cotton wool dressing was changed three times during the first 12 hours. By discharge, this had reduced to mild staining of slightly old blood. Susie was advised to change the dressing three times a day for the next 2 days and then daily until discharge had stopped. Susie communicated with staff and visitors by relying upon her left ear for hearing.

Discharge planning and patient education

Discharge planning and patient education begins in the preadmission clinic, and issues are reinforced throughout the patient’s hospital stay. Written advice sheets are an invaluable source of education and reassurance, as patients often experience difficulty in absorbing all the verbal information given by nurses and doctors. Box 12.7 illustrates discharge advice given to patients following ear surgery.

Box 12.7

Box 12.7 Discharge advice for patients following ear surgery

• Change the cotton wool in the opening of your ear canal every day. Take care not to remove the ear pack. If the pack falls out, contact the hospital for advice.

• A small amount of reddish discharge from the ear is normal. If this becomes offensive, appears yellow/green, or fresh bleeding is noted, contact the hospital.

• Protect the ear, when bathing/showering, with cotton wool dabbed with Vaseline. Keep water out of the ear canal for at least 1 month, as this can cause infection. Use a dry shampoo for 1 week, and do not go swimming for 1 month or as advised.

• If there are any stitches, you will be advised upon their removal.

• Mild dizziness is common for a few days. If this worsens, contact the hospital. Do not drive if dizzy, and refrain from working and any strenuous activity for 1–2 weeks, or as advised. If applicable, do not fly for at least 1 month, but clarify this with your doctor before you leave. Do not blow your nose or play wind instruments for 1 month. Sneeze with your mouth open. These precautions protect the ear and surgery from trauma.

• Hearing is often reduced for the first few weeks because of packing, swelling or discharge. Follow-up hearing tests will be performed.

• Pain is usually mild. If pain increases, contact the hospital.

• If concerned about any matter as regards recovery and aftercare, do not hesitate to contact the hospital.

Outpatient follow-up varies depending on the nature of the operation, and it can be between 1 and 6 weeks. Any aural packing is removed at the outpatient appointment, as well as a repeat aural examination and audiometry.

The nose

Anatomy and physiology

The nose is part of the respiratory system, and is responsible for the sense of smell (olfaction). The nose also contributes major aesthetic features to the face (Behrbohm et al, 2002). The nasal passages link the face, the paranasal sinuses and the nasopharynx.

The external nose

The upper third of the external nose consists of two nasal bones, which are fused together. The lower two-thirds are cartilage, the tip of which is especially pliable and is protected by fibrofatty tissue.

The nasal cavity

This consists of twin passages, divided and supported by the osteocartilaginous septum. The anterior opening of each passage is the vestibule, and is lined with skin and hair. The posterior opens into the nasopharynx and is termed the choana. Turbinates line the lateral wall of each side; there are usually three – superior, middle and inferior. They function to maximize the surface area of mucous membrane, enabling the warming and humidification of inhaled air. The space between the middle and inferior turbinates contains the ostiomeatal complex, which functions to drain the sinuses (Daya and Crittenden, 1998). Cilia contained in the epithelium beat constantly in order to transport mucus posteriorly to the nasopharynx (Citardi, 2001).

Vascular supply

The rich arterial blood supply to the nose derives from the external and internal carotid systems serving the sphenopalatine artery and the anterior ethmoid artery. Venous drainage is via the sphenopalatine and ethmoid veins.

Nerve supply

The olfactory nerve innervates smell receptors in the nasal mucosa. Fibres of this nerve pass through the roof of the nasal cavity in the ethmoid sinus at the cribriform plate, and form the olfactory bulb in the brain. Secretory glands of the nose are controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Sensory innervation of the nasal cavity is via the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve (Ugwoke et al, 2001).

Functions of the nose

Functions of the nose are:

• airway

• filtration and protection – by nasal hairs, mucus transport and cilia; and antibacterial action within the mucus

• humidification and warming – by blood and secretory glands

• olfaction

• resonance of sound.

The paranasal sinuses

The sinuses act as extensions of the nasal cavity. There are four pairs: frontal, sphenoid, ethmoid and maxillary.

Sinus functions include:

• mucus production

• air-filled cavities to reduce the weight of the skull

• protecting the eye and brain from trauma

• aiding sound resonance.

Conditions of the nose and sinuses that require surgery

There are a variety of conditions and diseases that benefit from surgical intervention. The following details the main examples, with types of surgery explained in Box 12.8.

• Disorders of the nasal lining: e.g. allergic rhinitis, sinusitis and nasal polyps.

• Disorders of the autonomic nervous system: namely, vasomotor rhinitis. An imbalance exists between parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve supplies to the nasal mucosa, resulting in increased vascularity of the turbinates and nasal obstruction.

• Structural disorders: e.g. deviated septum, septal haematoma, fractured nasal bones and irregular nasal bones.

• Infection: e.g. acute/chronic sinusitis. This is an inflammatory condition whereby the sinus ostia (natural sinus openings into the nasal cavity) become blocked. Mucus accumulates in the sinuses, is unable to drain and may become infected. If normal sinus clearance is not restored, this can lead to chronic mucosal thickening and subsequent nasal obstruction, headache, facial pain and purulent discharge.

Box 12.8

Box 12.8 Types of nasal and paranasal sinus surgery

Inferior turbinate surgery – for hypertrophy due to allergic/vasomotor rhinitis

• Diathermy: to scar/shrink mucosal lining of turbinate using bipolar, monopolar, laser or ablation methods

• Turbinoplasty: to reduce size of turbinate from within using a microdebrider

• Turbinectomy: partial or total removal – to increase airway patency

• Outfracture: to reduce size and function – to alleviate obstruction and symptoms of rhinitis

Septum surgery

• Submucous resection of septum: to straighten deviated septum, performed to increase nasal airflow

• Septoplasty: maximum septal cartilage is preserved; performed to correct septal deviation. Cartilage tissue may be reinserted, straightened, as supporting graft

• Drainage of septal haematoma: performed by either needle aspiration or formal incision

Nasal bones

• Rhinoplasty: external and internal bony and cartilaginous deformity is corrected, for aesthetics and function.

• Reduction of nasal fracture: to restore patency of airway and aesthetics of nose

Sinus surgery

• Polypectomy: nasal polyps can be removed using a microdebrider or surgical forceps

• Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS): aims to restore normal functional drainage of the sinuses; includes gentle removal of diseased mucosal lining and widening of natural ostium of each sinus

– Maxillary antrostomy

– Ethmoidectomy: posterior and anterior ethmoid sinuses gently debrided to improve mucus drainage

– Sphenoid sinus surgery: sphenoid ostia opened to minimize further obstruction

– Frontal sinus surgery: frontal recess opened to improve frontal sinus drainage

• External ethmoidectomy: an external incision is made to facilitate disease clearance. Improved endoscopic techniques have lessened the need to perform this surgery routinely. A good approach for tumour clearance

• Antral washout: saline is irrigated into the sinus via a cannula, and pus and mucus are expelled

• Caldwell–Luc procedure: the maxillary antrum is cleared of disease via an antrostomy made inside the upper lip. Endoscopic sinus surgery has diminished the need for this type of antrostomy

Specific investigations

Physical examination and a thorough history need to be taken. Conservative treatment is the desired option, with the prescribing of topical nasal and sinus preparations. The following investigations may be undertaken:

• allergy testing – to locate and eliminate allergens

• endoscopy – to visualize the nasal anatomy

• rhinomanometry – objective measure of impaired nasal breathing

• X-rays – reveal bony pathology

• CT scan – gives a detailed image of bony and soft-tissue disease

• MRI scanning – valuable in malignancy.

Nursing assessment of a patient requiring nasal/sinus surgery

Maintaining a safe environment

Because of the rich blood supply of the nose, there is a risk of haemorrhage following nasal and sinus surgery. Preoperative observation of the patient’s vital signs gives an accurate baseline for postoperative reference. A full medical and drug history may reveal conditions or medications that can exacerbate bleeding, e.g. blood clotting disorders or anticoagulant therapy.

Breathing

Conditions and diseases of the nose and sinuses often lead to nasal obstruction, snoring, obstructive sleep apnoea (cessation of breathing for intermittent periods while asleep) and mouth-breathing. Assessment of the patient’s respiratory rate, depth and rhythm is therefore indicated. The surgical insertion of nasal packing forces the patient to mouth-breathe, and this may be distressing. Chest conditions which may lead to respiratory difficulty are also noted, e.g. asthma.

Eating and drinking

Nasal packing makes this activity awkward, as a partial vacuum is created, and the patient may complain of a sucking sensation upon swallowing. Postnasal discharge, loss of sense of smell and the presence of blood in the mouth all hinder the desire to take diet and fluids.

Sleeping

Assessing the patient’s normal sleep pattern is useful. As discussed, nasal and sinus conditions often cause nasal obstruction, and this interferes with the activities of breathing and sleeping. The patient may be a snorer, suffer from interrupted sleep and dry mouth and may complain of fatigue. Postoperative nasal packing, swelling and discharge will also affect the patient’s ability to sleep; this tends to improve as recovery progresses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access