24. Patients requiring plastic surgery

Adèle Atkinson and Mary Smith

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Types of wound closure537

Skin grafts537

Flaps542

Use of leeches in reconstructive surgery551

Use of tissue expanders in reconstructive surgery552

Discharge planning555

Conclusion555

By the end of the chapter the reader will be able to:

• define plastic surgery

• appreciate the variety of reasons why patients have plastic surgery

• be aware of some of the psychological issues when caring for patients undergoing plastic surgery

• understand why flaps and skin grafts are used in plastic surgery

• describe the physiology of graft healing

• differentiate between a graft and a flap

• understand the principles of specific nursing care of patients with skin grafts and flaps and apply these to a variety of situations

• be aware of the need to give patient education/health education

• have an awareness of some of the ethical issues involved with caring for patients undergoing plastic surgery, e.g. informed consent.

Introduction

Traditionally, plastic surgery conjures up images of patients undergoing cosmetic surgery. However, this is only one part of plastic surgery. The British Association of Plastic Surgery Nurses states as one of its objectives: ‘To promote the advancement of research/education for those involved/interested in the nursing care of patients undergoing plastic surgery to include burns and maxillofacial procedures’ (BAPSN, 1992), which suggests that plastic surgery has a broader perspective.

Plastic surgery is derived from the Greek word plastikos, which means to mould or give shape (Goodman, 1988). It is also about the restoration of function and, up until the beginning of the 20th century, was more to do with reconstruction of congenital malformation or traumatic damage, rather than with cosmetic surgery (McCarthy, 1990). The authors agree with McCarthy that there is no real division between cosmetic and reconstructive surgery: for example, reduction mammoplasty (breast reduction) tends to bring with it relief from backache and gives the woman a more positive self-esteem; the removal of breasts from males who have gynaecomastia allows the boy/man to function without the psychological stigma of looking different from his peers. Both of these types of surgery may be considered as cosmetic surgery, but both allow the person to function more efficiently within society, with more positive self-esteem. Perhaps it is fair to say that plastic surgery involves using principles of reconstructive surgery and nursing care, whether this is in the treatment of congenital abnormalities, trauma, or the need to reshape normal structures to allow more positive self-esteem (Gladfelter, 1996).

The use of plastic surgergy techniques is becoming increasingly common on surgical wards: e.g. the use of flaps in breast reconstruction following mastectomy and the use of skin grafts to help heal wounds. It is also found increasingly in hand surgery on orthopaedic wards, in some aspects of paediatric surgery and in neurosurgery. This may be because in some trusts, patients are nursed on plastic surgery wards only long enough to have the operation and ensure the initial results are satisfactory, and then are either discharged home or back to the hospital ward from which they were referred. Or it may be because, with the advent of better microsurgical techniques (e.g. the free flap), there is more scope for use with other medical specialties.

Plastic surgery covers many of the areas of anatomy and physiology discussed in other chapters – for example, wound healing and breast surgery – and so these aspects will not be discussed here.

This chapter will focus mainly on nursing issues related to caring for patients who have skin grafts and flaps, with some discussion on the use of tissue expansion, and will refer to other types of closure where appropriate.

To show application of theory to practice, patient scenarios will be used. Roy’s (1976) model of nursing will be used to give structure to the assessment, planning and implementation of nursing. This particular model of nursing has been chosen because, within this specialty, the focus is adaptation, whether it is in terms of body image or physiological adaptation: e.g. restoration of function.

Roy’s adaptation model of nursing

Roy believes that health is a function of adaptation to stressors – physiological, psychological and social. Successful adaptation is equated with health, and the nurse’s role is to help the patient to adapt to stressors (Akinsanya et al, 1994).

The model identifies the adaptive or maladaptive behaviour in each of four modes (first-level assessment):

• physiological needs

• self-concept

• role function

• interdependence.

Problems – both potential and actual – can then be identified, as well as the relevant influencing factors.

A second-level assessment assesses the stimuli that influence the behaviour, and classifies them into focal stimuli (main cause of the problem), contextual stimuli (any environmental factor which contributes to the problem) and residual stimuli (any previous experience or attitudes/beliefs that may contribute) (Akinsanya et al, 1994).

Goals can then be set, as well as the appropriate interventions.

When nursing patients require plastic surgery, one main theme applies throughout – body image. It is important to recognize that, for whatever reason the patient is in hospital, there will probably be an element of alteration in body image (see Ch. 7 for issues and nursing interventions regarding body image).

Psychological concerns

People have plastic surgery for many reasons. Although each patient has individual needs, there are common psychological issues of which the nurse needs to be aware in order to deliver holistic nursing care (Price, 1990).

Unlike other surgical procedures, the outcome of any plastic surgery procedure is strongly influenced by how closely the result meets the patient’s desires (Goin and Goin, 1981). Therefore it is important for the nurse to clarify at admission what the patient perceives the outcome will be and how long the finished result is expected to take. This will usually have been discussed with the patient by a member of the medical team beforehand. For a patient to discuss such issues with nursing staff requires a trusting relationship, so the nurse must have good communication skills and be able to spend time with the patient, especially on admission. This aids the process of informed consent. Although issues surrounding surgery and informed consent are commonly acknowledged as the responsibility of the medical staff, nurses are often involved in this process. This may be to reinforce information or clarify and answer questions (Gorney, 1985). This process is facilitated by a good, collaborative working relationship between the multidisciplinary team.

For patients having plastic surgery, hopes and fears can become focused on their abnormality (Maksud and Anderson, 1995); therefore, it is useful to assess their motivation for having the procedure. Goin and Goin (1981)found that women were more likely to be happy with augmentation mammoplasty results if they wanted to have their breasts enlarged (internal motivation), rather than because their partner wanted them to (external motivation) or because they thought their partner was having affairs because they had small breasts. This concept can be taken further to include the nurse’s reactions to how the patient looks or to the type of surgery being performed. Therefore, it is important that the nurse is aware of their own body image and feelings, to allow a positive attitude to be conveyed to the patient through both verbal and non-verbal communication. Patients who believe the nurses to be concerned and caring appear to have a better postoperative recovery; they report fewer feelings of disappointment and are more satisfied with the outcome (Rankin and Mayers, 1996). This reinforces the need for patients to be adequately prepared for all stages of their stay in hospital: e.g. any drains that may temporarily alter their image of themselves; how much scarring there will be; the initial appearance versus the final outcome.

Issues can be discussed first at a pre-admission clinic, e.g. wound progression, and built upon during the patient’s stay in hospital through to discharge. It is important to discuss how the wound, etc., will progress, as the initial result may come as a shock to the patient: for example, a patient with a flap may initially see this as a ‘lump of meat’ on their body and this can then affect their body image. Photographs of similar surgery showing the ‘wound’ at differing stages may help here, as would talking to other patients.

Photographs can be taken, preoperatively and then postoperatively, while in hospital or at an outpatient clinic. Photographs show progression of healing: alterations of appearance can easily be seen, as can the extent of any injury or deformity. If necessary, such photographs also provide evidence for any legal situations. It must be remembered that written consent should be obtained prior to taking any photographs.

With planned surgery there is time to plan for a wound and strategies like those mentioned can be used. With unplanned surgery (usually as a response to trauma) there is shock (Magnan, 1996), with little time to come to terms with a wound or disfigurement. It seems fair to assume that the person with the most problems coming to terms with a wound would be the one with little time to plan (Atkinson, 2002). Therefore, the nurse should take their cue from the patient and discuss what the wound looks like when the patient is ready, and not when the nurse believes this should be discussed.

It is important that the nurse spends time with both types of patients, ensuring that they are aware of the likely course of events in terms of wound healing, scar formation and final appearance.

Types of wound closure

It is useful to be aware of all the methods of wound closure, before discussing some of the principles involved in caring for patients undergoing grafts and flaps.

The surgeon will always choose the simplest way to ensure wound coverage, and nursing considerations will vary depending on the type of wound closure.

The reconstructive ladder runs from the most straightforward to the most complicated:

1. Spontaneous closure: e.g. of small, uncomplicated wounds. These follow the normal manner of wound healing and are usually the sort of wounds that can be covered with a plaster.

2. Direct closure: e.g. using sutures, staples or steristrips (see Ch. 5).

3. Skin grafts: e.g. in burns, over some muscle flaps and over some donor sites of flaps.

4. Local flaps: e.g. in pressure ulcers and some facial wounds.

5. Tissue expansion: e.g. in breast augmentation, and to aid removal of some congenital naevi.

6. Free flaps.

Skin grafts

A skin graft is a piece of skin that has been totally separated from its blood supply and is used in another area of the body to reconstruct a defect (Dinman, 1996).

Types of skin graft

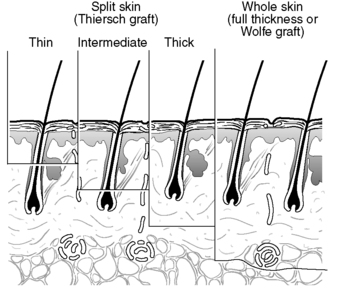

There are two main types of skin graft: split skin grafts (varying thickness) and full thickness skin grafts (Wolfe grafts) (Fig. 24.1).

|

| Figure 24.1 • Skin graft thicknesses. |

Split skin grafts tend to be taken from areas that can be hidden, e.g. buttock, inner thigh (Quaba, 1995), although skin can be taken from any area if necessary. They consist of skin taken from various thicknesses of the epidermis to the dermal layer, usually leaving enough epidermis behind for the skin to epithelialize. Full thickness skin grafts leave no skin structure from which regeneration can take place, and the donor site has to be closed by direct suture (Netscher and Clamon, 1994).

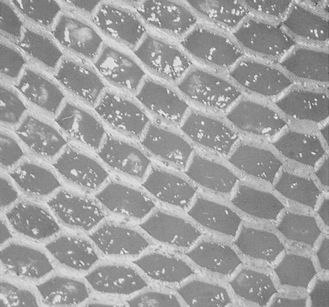

Split skin grafts can be meshed (Fig. 24.2) or unmeshed. Meshing allows the skin graft to be stretched and so cover a large area (rather like a string vest). It also allows exudate, which could prevent the skin graft adhering, to seep through (Quaba, 1995).

|

| Figure 24.2 • A meshed split skin graft. |

Indications for use

Skin grafts can be used to replace lost tissue: in burns or traumatic injuries; when tumours have been removed leaving wide surgical excisions; or when the rate of healing needs accelerating, for example in some ulcers or in the reconstruction of defects (Netscher and Clamon, 1994).

The disadvantage of using a split skin graft is that it contracts during healing (Goodman, 1988), and therefore its use is avoided in areas where this would be disastrous, e.g. on the eyelids. There is a lack of growth in the graft due to scar tissue, and this could be a problem in children. Because split skin grafts are fragile, they would not be useful in areas subjected to a lot of wear and tear, e.g. the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. In these cases full thickness grafts would be used, as they contract less: they also allow growth in children and are more durable (Quaba, 1995).

Full thickness skin grafts ‘take’ less readily than split skin grafts, because of their thickness. They must be fairly small because the donor area cannot regenerate and needs to be directly closed (Netscher and Clamon, 1994), and therefore they cannot be used for large areas.

Skin grafts can be taken from the patient’s own skin (autograft), from another living or dead person of the same species (homograft or allograft) or from another species (xenograft), usually the pig. Allografts and xenografts tend to be more commonly used for temporary skin coverage, as a biological dressing (Wong, 1995).

Allografts tend to adhere to the wound bed and provide a physiological environment at the wound surface which prevents bacterial invasion of the wound (Wong, 1995). Although allografts are more commonly used to treat patients with burns, they have also been used successfully as dressings for venous ulcers and to cover wounds where large congenital naevi have been removed (Wong, 1995).

Within Europe, skin can be stored in tissue banks: it either can be stored in liquid nitrogen and kept until required (Kakibuchi et al, 1996) or can be preserved in glycerol and kept at temperatures of 4–6 °C (Pianigiani et al, 2002).

Healing of skin grafts

For effective healing to take place, the wound site on which grafting will take place (the graft bed) must have a good, effective blood supply, be free from infection and have a healthy granulation appearance (McGregor and McGregor, 2000 and Quaba, 1995). This means a holistic assessment of the patient must be undertaken, which focuses not only on the wound but also on other factors which may influence healing (see Ch. 5). The graft bed can be any viable tissue – epidermis, dermis, fat, muscle, etc. – but not generally bone or tendon (Greenhalgh, 1996 and McGregor and McGregor, 2000), due to the limited/lack of blood supply.

Skin grafts can be taken under general anaesthetic or under local anaesthetic, using, for example, EMLA® cream (Bondville, 1994). Local anaesthetics tend to be used when small areas of skin are required, in children, and sometimes in elderly people, depending on their general health.

Excess skin is usually taken for use at a later date, in case further grafting is required. This excess skin will remain viable for up to 21 days if stored at a temperature of about 4 °C (Coull, 1991a and McGregor and McGregor, 2000). Clinical guidelines suggest skin should be stored in a specialized storage refrigerator and should be kept moist with saline at all times. The requirements of the European Directive (Department of Health, 2004) for storage of skin must also be adhered to.

The skin graft can be applied either in theatre or, if the wound bed is bleeding profusely, 24–48 hours later in the ward when bleeding will have stopped. The graft may be sutured, stapled or left with just a dressing on to aid healing (depending on surgeon’s preference).

To ensure viability, a split skin graft must gain a new blood supply within 2–3 days (Quaba, 1995). This process of skin graft ‘take’ starts as soon as the skin graft is placed on the wound bed.

Fibrin is exuded (part of the normal process of haemostasis), which allows initial adherence of the skin graft to the wound area or graft bed via weak fibrin bonds (Greenhalgh, 1996). This happens within a few hours and is called serum imbibition. At this point, nutrition to the graft is by diffusion from the plasma secreted by the graft bed (McGregor and McGregor, 2000). This is followed by a joining of the capillary networks in the skin graft to those in the graft bed. It takes approximately 24–48 hours for the endothelial cells from the blood supply within the graft bed to reach the split skin graft. This occurs in two ways: first, there is direct connection of the graft bed capillaries to the pre-existing ones in the graft (inosculation); secondly, the endothelial cells from the postcapillary venules of the graft bed migrate into the graft and form new capillaries which eventually reconnect to the arterioles in the graft bed (neoangiogenesis) (Greenhalgh, 1996). This is substantial enough to allow careful handling of the graft by about the fifth day (McGregor and McGregor, 2000). The lymphatic and nerve ‘link up’ happens more slowly (McGregor and McGregor, 2000). Finally, collagen bridges form across the graft bed to the graft (organization phase) (Greenhalgh, 1996) and fully stabilize the graft. Maturation occurs over many months. The adnexa, e.g. sweat glands, from the dermis will not be present in the grafted area (Greenhalgh, 1996) because they were left behind in the donor site and will not regenerate in the grafted area. This may cause the patient to feel itchy over the grafted area in hot weather.

If the skin graft is applied to a limb, the limb should be elevated, to aid venous return and reduce oedema, as with any injury to a limb. Due to the slow ‘link up’ of the lymphatic system, the need for elevation becomes more significant.

Skin graft dressings

A non-adherent dressing such as paraffin-tulle, Mepitel™ or Urgotul™ is used to aid graft ‘take’. This will ensure stability of the graft to the wound bed, while creating an appropriate environment to promote healing.

Although paraffin-tulle is described as a non-adherent dressing, it has a tendency to ‘dry out’ and can adhere to the wound as a result (Wilkinson, 1997), especially if the graft is exuding. This may damage epithelial tissue when removed, and the dressing may need to be soaked off to minimize trauma.

Mepitel™ is a non-adherent silicone dressing which is bound to a polyamide net. This open network structure allows any exudate to seep out onto a covering absorbent dressing. It adheres to healthy surrounding tissue, instead of the wound (Williams, 1995). This makes removing it pain-free, and avoids trauma to the underlying tissue. Mepitel™ also has the advantage that it can be left in place for 7 days if required, allowing the secondary dressing to be changed when necessary (Williams, 1995), so avoiding trauma to the new skin graft.

Urgotul™ is composed of a polyester net impregnated with hydrocolloid particles and dispersed in a petroleum jelly matrix (Edwards, 2002). The hydrocolloid and petroleum jelly combine to form a lipid–colloid interface that prevents the dressing adhering to the wound (Benbow, 2002). Exudate can drain through the open mesh but, unlike tulle, the newly formed tissue is prevented from growing into the mesh by the small diameter of the mesh (Benbow, 2002).

Topical negative pressure in the form of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) has also been used to prepare the wound bed in order to aid skin graft ‘take’ on wounds which may prove difficult, e.g. those in which the wound bed is heavily exuding (Mullner et al, 1997). This system works by using negative pressure to improve blood flow, promote moist healing, accelerate granulation time and reduce bacterial colonization (KCI International, 1994). Topical negative pressure has also been used on top of skin grafts (Argenta and Morykwas, 1997) with good results, although these grafts must be meshed to allow the exudate to be drawn through into the drainage canister. See Chapter 5 for more detail on the use of topical negative pressure.

Graft ‘take’

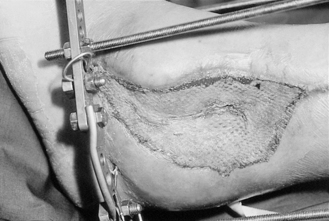

Whatever dressing is used, its removal at first dressing change is usually linked to the physiology of skin graft healing: i.e. the graft is inspected at either 2 days (when the blood supply is re-establishing) or 5 days, at which stage it should be well established; before that, the graft is friable and should be handled more gently. At first dressing the graft may look like Figure 24.3. The degree of ‘take’ is assessed, and this is usually written as a percentage – i.e. 50% ‘take’ if half of the graft has survived, or, in the case of Figure 24.3, 100% ‘take’. Any non-viable tissue is trimmed away, as this would provide a focus for infection. It is not unusual for the graft to be less than 100% ‘take’.

|

| Figure 24.3 • 100% ‘take’ of split skin graft at first dressing change. |

There are many reasons why the graft may not ‘take’. The graft bed may have been infected (common organisms include beta-haemolytic streptococcus – Lancefield group A, which digests the skin graft by fibrinolysis; and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which produces a green exudate which may cause the graft to lift off). The graft itself may have ‘sheared off’. The graft bed may have bled too much and prevented the graft from ‘taking’; or there may have been a collection of fluid under the graft, such as a haematoma or seroma (Coull, 1991a).

If all the graft has not ‘taken’, the underlying cause should be treated – e.g. antibiotics to clear an infection – before placing another skin graft to the area. If only part of the graft has ‘taken’, healing is encouraged by use of an appropriate dressing to encourage epithelialization from the graft into the wound and granulation of the wound itself.

Full thickness skin grafts

Full thickness skin grafts do not contract as much as split skin grafts and can be used in areas where any form of contracture would be detrimental, e.g. when reconstructing eyelids. Because the graft uses all the thickness of the skin, it can also be used in areas of wear and tear, e.g. on the soles of the feet. Only small areas of full thickness skin graft are taken, and the donor site is usually closed by direct closure because this area of tissue cannot regenerate owing to the lack of epithelial tissue.

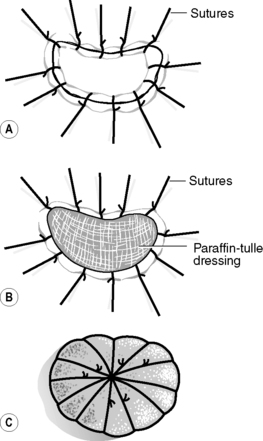

To aid full thickness skin graft ‘take’, the graft is sutured to the wound bed, a paraffin-tulle dressing is placed onto the graft, and a piece of foam is placed over the top as a dressing and a ‘tie-over pack’ is created (Fig. 24.4). The first change of dressing is usually done at 5 days to ensure that graft ‘take’ is well established. The dressing is removed by cutting the sutures over the foam dressing and then removing the dressing. Again, any non-viable tissue is removed and the skin sutures are taken out. The principles of care are the same as for split skin grafts.

|

| Figure 24.4 • Tie-over pack: (A) sutured full thickness skin graft; (B) covered with paraffin-tulle; (C) covered with a foam dressing and sutures tied over the top. |

The donor site

In a donor site of a split skin graft there remains enough epidermis (usually from the base of the hair follicles in the dermis) for healing to occur by epithelialization. Healing takes anything between 7 and 15 days, and therefore the first dressing change will be between 10 and 14 days, depending on the type of dressing used. If healing has not totally occurred, granulation is encouraged through use of an appropriate dressing. The donor site generates a lot of pain for the patient because it is a superficial wound (rather like a graze) and has plenty of exposed nerve endings. Patients often find the donor site more painful than the skin grafted area.

Wilkinson (1997) states that there are seven characteristics of an ideal donor site dressing. It should:

• retain moisture and warmth at the junction between wound bed and dressing

• remove or absorb excess exudate

• be painless to apply and remove

• inhibit multiplication of bacteria

• stay in place

• be easy to use

• be cost-effective.

Dressings that meet most of these requirements are:

• alginates, e.g. Kaltostat™, Sorbsan™

• Hydrofiber™, e.g. Aquacel™ (now reclassified as a protease modulating matrix dressing)

• hydrocolloids, e.g. Granuflex™, Urgotul™

• foam dressings, e.g. Lyofoam™, Alleyvn™.

• semipermeable films, e.g. OpSite™, Tegaderm™

Traditionally, paraffin-tulle, gauze padding and a crepe bandage have been used for donor site dressings. However, these have been found to slip down the patient’s legs, thus making them uncomfortable and painful. In addition, granulation tissue may grow through the tulle net spaces if left undisturbed, as would be the case with a donor site dressing (Wilkinson, 1997). As previously mentioned, tulle may also be painful to remove, may dry out, and, if over-applied, may cause maceration of the wound. Perhaps, for these reasons, more ‘modern’ dressing products should be used.

Alginates have been developed to cope with moderately or heavily exuding wounds and also have haemostatic properties. Donor site wounds have been found to heal quicker, with a better cosmetic appearance, using alginates, than with more conventional dressings, e.g. paraffin-tulle with gauze padding (Thomas, 1992). Once haemostasis has been achieved, it may be necessary to place another piece of the dressing over the top to allow for further absorption (Wilkinson, 1997). A secondary dressing is needed to keep the dressing in place and aid moist healing; this could be either a semipermeable film dressing or a hydrocolloid.

There is only one Hydrofiber™ dressing (which has now been reclassified as a protease modulating matrix dressing) – Aquacel™ (see Ch. 5 for further details). Like the alginates, Aquacel™ has been developed to absorb exudate from moderately or heavily exuding wounds. Morgan (2004) found that it is capable of absorbing 50% more than the alginates and therefore would be appropriate for donor sites. Again, a secondary dressing is needed to keep the dressing in place and aid healing; this could be either a semipermeable film dressing or a hydrocolloid.

Hydrocolloids have been used to good effect on donor sites and have been found to decrease the rate of wound infection (Smith et al, 1994), but hydrocolloid wafers do not adhere well to wet wounds (Coull, 1991b), so a large margin may be required, making it less suitable for large donor areas. There is also a problem of leakage from beneath the dressing (Porter, 1991), which the patient may find distressing. However, some hydrocolloids such as Comfeel Plus™ contain an alginate, making them more appropriate for small donor sites. They also cause less pain on removal than conventional dressings, due to their gelling properties. Unlike some of the other hydrocolloids, Urgotul™ has no adhesive layer and therefore may be an ideal alternative.

Foam dressings are hydrophilic and semiocclusive, with a low adherence to the wound bed (Wilkinson, 1997) and can be used with heavily exuding wounds. They can be left on the donor site for several days, depending on the amount of exudate. They also cause less pain on removal than conventional dressings, as they should not ‘stick’ to the area.

Semipermeable films have been used in the past, but exudate tends to collect under the dressing, causing it to lift off (Coull, 1991b and Wilkinson, 1997), as it has no capacity to absorb the exudate; consequently, these dressings are inappropriate for donor sites when used alone. However, as previously mentioned, they are used as a secondary dressing with alginate and Hydrofiber™ products to maintain a moist environment.

Patient education

Once the donor site has healed, it will look dry, because of the reduction of sebaceous glands which have been removed, and it will be red and itchy (Wilkinson, 1997). The area should be massaged at least three times a day with a moisturizer to keep the area hydrated and to help reduce scarring, which will eventually become paler and fade over the next year. Although the main benefit is from the massaging of the scar, the moisturizer provides a base which prevents friction and therefore prevents newly healed skin from being broken down. This applies equally to the skin grafted area. Massaging should start as soon as the skin is healed.

If the scars are unacceptable to the patient in terms of colour or body image, the patient can be referred to agencies such as the Red Cross, which will give advice on the use of cosmetic camouflage. It may be necessary to refer the patient to a support group such as Changing Faces or Let’s Face It, to help the patient with coping strategies for their new body image. Specific nursing strategies are explored in Chapter 7, with regards to helping patients with their altered body image.

Advice should be given on keeping both the skin grafted area and the donor site out of the sun as much as possible, as well as discussing the need for high-factor sun creams to be used over the areas. This is because the healed skin is extremely sensitive to the sun and will burn easily.

For an example of the nursing care given to someone who has a skin graft applied, see Boxes 24.1 and 24.2 and Table 24.1.

Box 24.1

Box 24.1 Example of preoperative nursing assessment, using Roy’s adaptation model of nursing, of a patient who will have a skin graft applied

Mr Jones, a 38 year old builder, is to have a malignant melanoma removed from his back. The defect will be covered with a split thickness skin graft. The donor area is his right thigh.

Mr Jones is married with two school-aged children. His wife works part time, as a helper, at the local nursery school.

The first level assessment, on admission, is as follows:

Physiological

• Oxygenation

– Colour good, no problems breathing. Admits to smoking 5–10 cigarettes a day

– Blood pressure: 120/80 mmHg; pulse: 80 bpm

• Nutrition

– Healthy appetite. No special needs

– Weight: 70 kg

• Elimination

– No problems discussed

• Activity and rest

– Is used to being very active. Is a member of a local gym and ‘works out’ three times a week. Participates in outdoor sports

– Sleeps on his back, for about 8–9 hours a night

• Protection

– Skin intact. Has a malignant melanoma on the middle of his back

– Admitted for removal of malignant melanoma, which will give two wounds: split skin grafted area, donor site

– Temperature: 36.8 °C

• Senses

– Hearing: normal

– Sight: no problems, does not wear glasses

• Fluid and electrolytes

– Well hydrated

– Admits to drinking ‘socially’ at the weekend

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access