20. Patients requiring gynaecological surgery

Jacky Cotton

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system398

Specific investigations for patients requiring gynaecological surgery399

Assessment of patient requiring gynaecological surgery404

Minor gynaecological surgery406

Laparoscopic surgery408

Nursing care for minor gynaecological and laparoscopic surgery409

Myomectomy415

Hysterectomy416

Nursing care for major gynaecological surgery418

Endometrial ablation426

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system428

Vaginal repair surgery/colporrhaphy428

Continence surgery429

Nursing care for patients requiring vaginal repair and continence surgery430

Laparoscopic treatment of ectopic pregnancy431

Treatment for gynaecological cancers433

Conclusion436

After reading this chapter the reader will understand:

• the relevant anatomy and physiology of the female reproductive system

• specific investigations that may be required by a woman undergoing gynaecological surgery

• different types of gynaecological surgery

• what women will experience in hospital and during recovery at home

• discharge advice for specific operations

• sexual aspects of gynaecological surgery.

Introduction

Surgery on any part of the body is likely to cause anxiety, but gynaecological surgery is a particularly sensitive area. Outpatient appointments and admission to hospital often involve vaginal examinations – the most personal of all medical examinations, and a cause of anxiety to many women (Selby, 2005). It is crucial to gain a woman’s confidence and provide a relaxed environment where her dignity and privacy are maintained.

Gynaecological surgery may also pose a threat to a woman’s concept of her body image, her role as a woman and as a mother, her sexuality and her relationship with her partner (Lee, 2005).

A major area of concern to many women is their femininity – and, often, fertility – following surgery, and this is a subject often forgotten by nurses. Webb (1985) stresses that the more knowledge people have about human sexuality, the more open and flexible they are likely to be towards their own and others’ behaviour.

The aim of this chapter is to promote awareness of the wider issues of the psychological effects and related sexuality surrounding gynaecological surgery. Nurses will then be better informed to care sensitively for these women.

Anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system

The female reproductive system consists of the internal genitalia situated in the pelvis – two ovaries, two Fallopian (or uterine) tubes, uterus, cervix, vagina – and the external genitalia, comprising the vulva.

The ovaries

The two almond-sized ovaries are the female gonads or sex glands. They lay either side of the uterus within the pelvic cavity. They measure about 3.5 cm in length, 2 cm in depth and 1 cm in thickness. Each ovary is attached to the broad ligament by a thin mesentery, the mesovarian. The ovaries obtain blood from the ovarian arteries, arising from the dorsal aorta on the posterior abdominal wall.

The ovaries produce ova or eggs, and secrete the hormones oestrogen, progesterone and small amounts of androgens.

The ovary is composed of a cortex and medulla. It is surrounded by a layer of germinal epithelium.

At birth, each ovary contains at least two to three million primordial follicles. Some of these follicles will develop within the ovarian cortex and become mature cystic follicles. These are known as Graafian follicles. The ovum is embedded within the Graafian follicle, and, when mature, one will be released each month, at ovulation, ready for fertilization by a sperm.

Ovulation occurs 14 days before the onset of menstruation, midcycle in a 28-day cycle. Some women experience pelvic pain each month when ovulation occurs, known as ‘mittelschmerz’. Conception is most likely to occur shortly after ovulation.

The menstrual cycle prepares the uterus for pregnancy. If conception occurs, menstruation does not take place. If the ovaries are removed, menstruation ceases and pregnancy cannot occur.

The menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle occurs in most women every 28–39 days, but may vary from 21 to 42 days. It is controlled by ovarian and pituitary hormones.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary gland causes the follicle to grow and stimulates the granulosa cells in the Graafian follicle to produce oestrogen. As the level of oestrogen rises, it inhibits further production of FSH but stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone (LH), and ovulation occurs.

Accompanying the ovarian and pituitary cycles are a series of changes in the uterine endometrium. When menstruation occurs, the endometrium is shed down to its basal layer and is accompanied by bleeding. Under the influence of oestrogen, regeneration begins and the endometrium grows thicker. This is the proliferation phase and lasts about 10 days.

Following ovulation and the production of progesterone, the endometrium becomes thicker and the glands more tortuous. This is the secretory phase and lasts about 14 more days, after which the lining is shed again.

After the discharge of the ovum from the Graafian follicle, the granulosa cells multiply rapidly and a convoluted, solid greyish body is formed. This is known as the corpus luteum and it functions as an endocrine gland, secreting oestrogen and progesterone. It persists for about 14 days, after which it degenerates if fertilization has not occurred.

When pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum continues to produce both oestrogen and progesterone for about 12 weeks, after which the placenta takes over the production of these hormones.

The corpus luteum is sustained by human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), which is produced by the cells of the trophoblast (embryo) from the time of implantation.

The Fallopian tubes

Two Fallopian tubes (also known as uterine tubes) join the uterus just below the fundus, or upper part, of the uterus. Each tube is 10–14 cm long and opens out into a funnel-shaped structure of small, finger-like projections, known as fimbriae, which are positioned close to the ovaries during ovulation.

The tubes are mobile, which enables them to pick up eggs (ova) released from the ovaries and carry sperm upwards to meet them. Fertilization takes place in the tubes, which then carry the fertilized ovum into the uterus, wafted along by the ciliated epithelial cells which line the tubes.

Uterus

The uterus is a hollow, pear-shaped muscular organ lying between the bladder and the rectum. It is made up of the fundus, body and cervix.

The thick muscular wall of the uterus is called the myometrium, while the body of the uterus is lined with a mucous membrane called the endometrium. This is a very vascular layer which differs in thickness throughout the menstrual cycle and is largely shed during menstruation.

The uterus normally lies in an anteverted position, meaning that the long axis of the uterus is directed forwards. It is held in place by muscular and fibrous supports. The muscle is arranged in a spiral form running from the cornu to the cervix, giving a circular effect around the Fallopian tubes and cervix, and an oblique effect over the body of the uterus. The important muscular supports are the levator ani muscles. The uterine ligaments include:

• anteriorly – the round ligaments

• laterally – the transverse cervical ligaments

• posteriorly – the uterosacral ligaments.

The broad ligaments, although referred to as a ligament, are folds of peritoneum attaching the uterus to the pelvic side walls, helping to hold the uterine fundus in an anteverted position (Tortora and Grabowski, 2003).

The blood supply to the uterus is derived from two pairs of arteries: the uterine and ovarian arteries.

Cervix

The cervix is the neck of the uterus and extends into the top of the vagina. The cervix is 2–3 cm long and dilates during childbirth to allow the passage of the baby.

The outer surface of the cervix in the vagina is covered with squamous epithelium. Squamous cells begin to grow from beneath the columnar epithelium and gradually replace it. The point at which the squamous cells of the ectocervix (outer cervix) meet the columnar cells of the endocervix (inner cavity) is known as the squamocolumnar junction.

The normal replacement of one type of cell by another is called squamous metaplasia, and where it takes place is called the transformation or transitional zone. During the menstrual cycle the glands in the cervix respond to rising levels of oestrogen by secreting an abundance of mucus. Changes occur in the consistency of the mucus during the cycle and followers of ‘natural family planning’ or Billings method (Billings and Westmore, 1980) rely on these changes to predict their fertile period. This mucus is alkaline and neutralizes the acidic vaginal secretions.

Vagina

The vagina is a muscular canal joining the uterus to the external genitalia. It is about 8 cm long, and normally the anterior and posterior walls are in close contact with one another. They lie in folds called rugae, which expand during sexual intercourse and childbirth.

During the reproductive years, Döderlein’s bacilli, a form of lactobacilli, appear in the vagina and produce lactic acid by acting on the glycogen in the epithelial cells. This results in a vaginal environment with a pH of 4, which helps prevent infection.

Vulva

The vulva (meaning ‘cover’ in Latin) is the collective name given to the external female reproductive organs. It extends from the mons pubis to the perineum and is bounded by the labia majora.

Specific investigations for patients requiring gynaecological surgery

Pelvic examination

Vaginal examination

After a thorough history has been taken from the patient, the gynaecologist will usually wish to perform a vaginal examination. This may be a digital examination, or involve the insertion of a speculum. This is a most intimate procedure, and most women worry about this aspect of a gynaecological outpatient appointment. It should never be carried out without a female chaperone present. It is crucial that the nurse acting as a chaperone provides support and explanation to the woman, ensures privacy and maintains the woman’s dignity at all times. The nurse should continually talk to the woman, encouraging her to relax and breathe deeply. Some women prefer to be told exactly what is happening; others like to be distracted by talking about family or holidays, etc. The patient should be advised that the more relaxed she is, the less uncomfortable the examination. It is advisable that the woman empties her bladder first and is allowed to remove her underclothing in private. A blanket should always be available to maintain her dignity during the examination.

Speculum examination

The clinician will often need to use a speculum to view the cervix. The most common type of speculum is a Cusco’s or bivalve speculum, which parts the vaginal walls, enabling the cervix to be visualized. A high vaginal swab may be taken if any discharge is present, and in sexually active young women a chlamydia swab may be taken. Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted infection which may be difficult to detect since often women have no symptoms. It can cause pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility (Sutton, 2001).

Less commonly, a Sims’ speculum may be used with the woman lying in a modified left lateral position. It is used to detect any prolapse of the uterus or vaginal wall. The woman may be asked to cough to demonstrate any signs of stress incontinence.

Bimanual palpation

Often, a woman will be examined both abdominally and vaginally in the outpatient clinic. After the gynaecologist has palpated the abdomen, the woman will be asked to draw her knees up with her ankles together, and asked to relax her knees apart. This is the dorsal position and is most commonly used, since it is convenient for bimanual palpation.

The procedure is carried out with two hands palpating together, one on the woman’s abdomen, pressing down on the fundus (top) of the uterus, and one inside the vagina. The size, position and movement of the uterus are determined. Other structures such as the ovaries and Fallopian tubes are located. Any masses, such as a pregnancy, ovarian cyst or tumour, are noted.

Cervical screening

This is performed by examining cells from the cervix and identifying early changes, which might lead to squamous cell carcinoma.

For a smear test, the cells are obtained during a speculum examination using a brush. Cells are taken from the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, where most precancerous changes originate (Hughes, 2001) and then sent to the laboratory for histological examination. A new screening test uses liquid-based cytology. Here, cells are obtained from the cervix using a small brush. The head of the brush is put into a small vial containing preservative fluid or is rinsed directly into this fluid. In the laboratory the sample is spun and a random sample of the remaining cells is taken. A thin layer of the cells is then put onto a slide. This is examined under a microscope. The conversion to this technique was completed in October 2008.

All women during their reproductive years should have a smear test every 3 years from age 24 to 50, then 5 yearly until 65 (NHS Cervical Screening Programme, 2008). If a woman has an abnormal result, the frequency is increased.

Sometimes the cervix may appear red. This is a normal physiological state and occurs when there is only a single layer of columnar cells covering the connective tissue and blood vessels. In the past, this condition has been called an ‘erosion’, but the correct term is an ‘ectropion’.

Any abnormal or dyskaryotic cells are known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). There are three stages of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

• CIN 1 refers to cells that have minor changes in cell structure which are the first signs of precancer. Approximately one-third of CIN 1 cases revert to normal (Hughes, 2001). Repeat smears may be required more frequently, depending on local policy.

• CIN 2 is the next stage, which usually correlates with moderate dyskaryosis where there are more marked changes. A repeat smear or colposcopy is usually recommended.

Clinical studies have shown that 99.7% of cases of cervical cancer are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) (Walboomers et al, 1999). In September 2008, a national immunization programme to protect against HPV was introduced in the United Kingdom for girls aged 12–13 across the UK. In autumn 2009, a 2 year catch-up campaign will vaccinate all girls up to 18 years of age.

It will be many years before the vaccination programme has an effect upon cervical cancer incidence, so women are advised to continue accepting their invitations for cervical screening (NHS Cervical Screening Programme, 2008).

Colposcopy

Colposcopy is the observation of the cervix and its surrounding tissue with binocular magnification. A microscope is used, which allows magnification of up to 10 times.

Colposcopy is usually undertaken in a gynaecology outpatient department, a specific colposcopy unit or a genitourinary department. Many nurses have undergone specialist training and perform the role of nurse colposcopist, undertaking both diagnostic colposcopy and treatments. This is often more acceptable to women than being treated by a male doctor. It is advisable to explain to the woman that the large-looking microscope and its attachments will not go inside her. In fact, the procedure is similar to taking a cervical smear, apart from the fact the woman’s legs will be in a lithotomy position, i.e. in stirrups. A biopsy may also be taken under a local anaesthetic. In many units, the woman may be given the opportunity to view her cervix on a television screen.

Colposcopy is indicated when there have been changes in the cells of the cervix, noted on the woman’s smear test. It enables the position and extent of the CIN to be ascertained, so that the correct management is chosen. Increasingly, treatment can be carried out at colposcopy, using local ablative therapy such as cold coagulation or diathermy loop excision, eliminating the need for general anaesthetic.

Discharge advice following colposcopy

• There may be a bloodstained discharge or it may be watery. A panty liner should be used for sufficient protection. Tampons should not be used for the first period after treatment, to reduce the risk of infection.

• Follow-up is crucial to the ongoing care of women who have had an abnormal smear test. Most women will have a follow-up colposcopy after 6 months and then annual smears for 2 years.

• If the woman has had treatment to the cervix, she should refrain from sexual intercourse for 4–6 weeks to enable the biopsied area of the cervix to heal. Signs of local infection include heavy fresh bleeding or an offensive-smelling discharge.

Pelvic ultrasound scan

Ultrasound is used as a means of examining various organs of the body by means of high-frequency sound waves. These form pictures on a screen and enable any abnormalities to be detected. The uterus and ovaries can be identified and any tumour located and measured. During the menstrual cycle, the growth of a Graafian follicle may be observed and the thickness of the endometrium measured, so that the timing of ovulation is confirmed.

A full bladder is necessary as it helps push the uterus and ovaries into a better position for examination. The woman should fill her bladder by drinking 1 L of fluid (not fizzy drinks) during the 2 hours before the appointment. This can be very uncomfortable for the woman.

The procedure takes between 5 and 10 minutes and is not painful but may be uncomfortable. This is because the radiographer has to press firmly, using cold gel, against the abdomen and full bladder, in order to produce a clear picture.

Transvaginal ultrasound scan

This type of scan facilitates a much clearer view of the abdominal organs than an abdominal scan. It is useful in confirming the presence of an early intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy, and a missing intrauterine contraceptive device may be located. An ultrasound scan cannot harm a pregnancy.

The tip of a round-edged probe is covered by a disposable condom, and then inserted into the vagina.

Hysterosalpingogram

A hysterosalpingogram (HSG) is an X-ray examination of the female genital tract and takes about 15–20 minutes. The test must be done during the first 10 days of the cycle, after menstruation has ceased, but before ovulation. It must not take place during the follicular phase, as it could disturb a pregnancy if conception has occurred. An HSG should not take place if there is evidence of active infection, since infected material could enter the tubes.

Radio-opaque dye is injected into the cervical canal via a cannula. The dye may cause a warm flush in the abdomen, with some abdominal cramping pains. Progress of the dye through the uterus and Fallopian tubes can be followed on a television screen. The dye is harmlessly absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted via the urine.

An HSG is a diagnostic aid and demonstrates internal uterine abnormalities such as fibroids, a bicornuate uterus, or tubal occlusion in cases of infertility. If the Fallopian tubes are patent, radio-opaque dye will spill into the pelvic cavity. An alternative to this procedure is the ‘laparoscopy and dye’ test, which has to be performed under general anaesthetic.

The procedure has also been developed to treat blockages and this is known as a selective salpingogram. After visualizing a blockage of the Fallopian tube, a small wire is guided through a tube into the Fallopian tube to try and open any blockages.

Hysteroscopy

This procedure allows the gynaecologist to view directly inside the uterus and examine the endometrium. A small fibreoptic telescope is passed through the cervix into the uterus. The walls of the uterus are separated with gas or fluid to enable the telescope to view inside the uterus. This procedure is not usually carried out if the woman is bleeding vaginally, since this can impair the view.

Hysteroscopy may be used to diagnose the cause of postmenopausal bleeding, and in this instance an endometrial biopsy will be taken. Hysteroscopy is increasingly performed as an outpatient procedure, avoiding the need for a general anaesthetic.

Laparoscopy

This test enables the direct visualization of the pelvic organs using a fibreoptic light and a telescope-like instrument known as a laparoscope. Under general anaesthesia, the woman is catheterized and placed head downwards in the Trendelenburg position to allow the upper abdominal contents to fall away from the pelvic organs. A small incision is made below the umbilicus, and 2–3 L of carbon dioxide is introduced into the abdominal cavity. This helps to displace the intestines and allows the pelvic and abdominal organs to be viewed easily via the laparoscope. A second instrument is inserted through a small cut near the upper pubic hairline.

Thorough observation of the pelvic organs can then be undertaken. As an investigation for infertility, methylene blue is injected through the cervix and observed via the laparoscope as it passes through the Fallopian tubes and out via the fimbrial ends into the pelvic cavity. The dye illustrates any blockages in the tubes which might prevent the eggs from the ovaries reaching the uterus. If the dye flows through, the tubes are assumed to be patent, although the state of the cilia in the lining cannot be seen. If the test is performed during the follicular phase of the cycle, developing follicles may be viewed.

The woman should be warned that she may feel bloated and have an aching pain around the shoulders. This is quite normal and is caused by the carbon dioxide in the abdomen irritating the phrenic nerve. Paracetamol and hot peppermint water can give relief. Sometimes the incisions may bleed or ooze a little, but an ordinary plaster should be a sufficient covering. There may be blue staining on her sanitary towel, and urine may appear green or blue as it mixes with dye from the vagina.

Developments in laparoscopic techniques mean that procedures previously carried out through an open laparotomy, such as oophorectomy, are now done through laparoscopy, resulting in a quicker recovery time.

Urodynamic investigations

When a woman complains of stress incontinence, it is important to ascertain whether she has genuine stress incontinence, which may be treated surgically, or detrusor instability, which does not require surgery.

• Genuine stress incontinence is defined as ‘the involuntary leakage of urine in the absence of detrusor activity’ (McKay Hart and Norman, 2000). There may be displacement of the bladder neck due to pelvic floor weakness, which prevents it responding normally to increases in intra-abdominal pressure such as coughing.

• Detrusor instability (also known as unstable bladder) refers to a condition whereby the bladder contracts uninhibitedly during bladder filling. This leads to symptoms of frequency and urgency.

Urodynamic investigations measure changes in bladder pressure with changes in bladder volume. This investigation is recommended to demonstrate specific abnormalities before undertaking complex urological procedures (NICE, 2006). A catheter is inserted into the bladder, and a pressure catheter is placed in the rectum to measure abdominal pressure. This eliminates movement artefacts which may be produced if the intravesical pressure alone is measured. The rectal pressure is subtracted from the intravesical pressure to give the detrusor pressure.

The bladder is filled at a fast rate of 100 mL/min. The woman indicates when she first feels the sensation of filling and when her bladder feels full. The water flow is switched off; she then stands up and is asked to cough to demonstrate any urinary leakage. She then sits on the uroflowmeter (a commode-like lavatory) and empties her bladder in private while the peak flow rate and maximum volume pressure are noted.

Videocystourethrography (VCU) can also be carried out, which allows visualization of the urethral sphincter mechanism and demonstrates any associated bladder pathology. This is particularly useful if the patient has previously had continence surgery or there is a medical indication for an X-ray.

Ambulatory urodynamics may be required if the results of normal urodynamics are inconclusive, or the patient still has symptoms and is not responding to treatment. This uses special equipment and lasts for 4 hours. Pressure catheters are placed in the bladder and rectum as for urodynamics but the patient is encouraged to mobilize. Measurements are checked every hour.

Cystoscopy

This procedure involves the thorough examination of the bladder under a general anaesthetic. A cystoscope, a fine telescope-like instrument with a light source, is inserted into the urethra and passed into the bladder. This enables the urogynaecologist to view inside the bladder, and a biopsy may be taken.

This operation is carried out to investigate the cause of recurrent urinary tract infections or haematuria (blood in the urine). Small polyps in the bladder or a caruncle (a small fleshy lump) at the urethral entrance can be removed during the procedure.

Occasionally, a woman may have a urethral catheter inserted at the end of the procedure if it is felt that the bladder needs to be rested.

Pregnancy testing

A diagnostic pregnancy test detects human chorionic gonadotrophin, which is excreted in the urine. The level of this marker hormone in blood and urine reaches its highest point in normal pregnancy between the 8th and 12th weeks. However, modern pregnancy testing kits are now so sensitive that they can detect a level as low as 25–30 IU/L.

Human chorionic gonadotrophin levels in an ectopic pregnancy (i.e. one occurring in a Fallopian tube) are lower than those found at a comparable period of gestation in a normal pregnancy. In instances of suspected ectopic pregnancy, the measurement of serum concentration of the β subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) is of great value, especially when used in conjunction with ultrasound scanning.

The level of β-hCG in a viable intrauterine pregnancy doubles approximately every 2 days. At a titre of 1000–1500 IU/L, it should be possible to detect an intrauterine sac on a transvaginal scan. Absence of β-hCG eliminates pregnancy, but levels above 1500 IU/L in the presence of an empty uterus may indicate a pregnancy of unknown location (PUL), often referred to as ectopic, or a very early intrauterine pregnancy. Repeat blood tests may be required after 48 hours to assess both the amount and rate of increase of β-hCG levels.

Rhesus status

After a pregnancy loss, whether a miscarriage, termination or an ectopic pregnancy, it is crucial that a woman’s rhesus status is checked to prevent haemolytic disease of the newborn in future pregnancies.

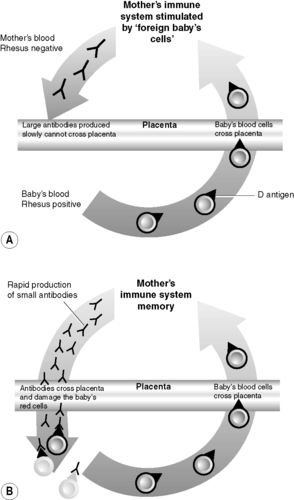

The rhesus factor is found in the red blood cells of 85% of the population (rhesus-positive); the other 15% are rhesus-negative (Tortora and Grabowski, 2003). If a mother is rhesus negative and the fetus is rhesus positive and a small amount of fetal blood passes into the mother’s blood stream, her body will be stimulated by these foreign cells and she will start to make rhesus antibodies. If the pregnancy continues there will be no harm to the fetus. However, once the antibodies have been produced these could affect future pregnancies. If a subsequent fetus is rhesus negative, there will be no problem as they do not have Rhesus antigens. However, a rhesus positive fetus will have rhesus antigens. The antibodies in the mother’s blood will cross the placenta and attack the fetus’s red blood cells causing haemolysis (Fig. 20.1).

|

| Figure 20.1 • Rhesus disease and (A) first and (B) second pregnancies. (Reproduced with permission from Baxter Healthcare.) |

Rhesus disease may be prevented by the injection of immunoglobulin ‘anti-D’, which destroys any rhesus-positive cells that have entered a woman’s bloodstream. It therefore prevents the woman’s body from making the antibodies, but must be given within 72 hours of the placenta separating.

Assessment of patient requiring gynaecological surgery

The majority of gynaecological operations are undertaken as planned elective admissions, giving nurses the opportunity to prepare a woman both physically and psychologically for surgery. Gynaecological nursing is a particularly sensitive area, and very often the ward nurse is the first person a woman can talk to openly about her problems and anxieties. Once a diagnosis has been made, finding an empathetic listener can be the first step a woman takes in coming to terms with a difficult diagnosis, be it an unwanted pregnancy or a suspected cancer. It is important that a full nursing assessment is made as soon as possible after admission and the nurse establishes a rapport quickly so support can be provided for the woman, who may find the situation both distressing and embarrassing (Cotton, 2003). Following surgery, women are being discharged back to their families earlier, reducing postoperative complications and recovery time.

Many hospitals provide preadmission clinics several weeks before the operation date. The woman will visit the clinic, where a nurse will assess her health status. Ward procedures and the planned surgery will be explained, information leaflets given and any preoperative investigations performed. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence has produced guidelines for routine preoperative tests based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) grading and grading of surgery booked (NICE, 2003). These may include a full blood count, and group and save for women undergoing major surgery. Here, the laboratory saves some of the patient’s blood so that it can be crossmatched with appropriate units of blood in case she should haemorrhage during surgery. Electrophoresis is required for those of Afro-Caribbean and Mediterranean origin to exclude sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia. Women aged 60 years old or above often require an electrocardiogram to detect any unknown cardiac problems.

In many units, preoperative assessment is performed by the nurse. This is to establish a baseline assessment from which change and progress may be compared. It is important to obtain a general medical and social background, as well as a specific obstetric and gynaecological history. An obstetric history listing pregnancies, miscarriages and terminations should be obtained, although some women prefer that any terminations revealed are not actually recorded. For women undergoing continence surgery, any babies weighing more than 8 lb should be noted and the length of labour and type of delivery are also pertinent. A long labour resulting in a forceps delivery may damage the pelvic floor and urethra. The terms ‘gravida’, meaning ‘pregnancy’, and ‘para’, meaning ‘live children’, are often used. Thus, a woman described as being G4 P2 2TOP means four pregnancies leading to two live children and two terminations.

A menstrual history is also recorded. Every woman has her own idea of what a ‘normal’ period is like, and therefore it is helpful to ask specific questions such as how many pads/tampons a day does she uses during a period. The length of the period and duration of cycle are important, as is the occurrence of any dysmenorrhoea (moderate-severe period pain) and premenstrual tension.

Any contraception used should be noted. Women using the oral contraceptive pill may be advised to stop taking it before surgery, due to the risk of developing deep vein thrombosis following surgery.

An assessment of bowel and urinary function should also be carried out. Many women suffer constipation following surgery. It is helpful to know if a woman suffers from this preoperatively as well, to plan her care accordingly. An overview of a woman’s bladder dysfunction is particularly important if she is undergoing continence surgery. Urinary incontinence has been a ‘taboo’ subject for many years, and women have often been too ashamed or embarrassed to admit that they leak urine. Asking the woman direct questions at an appropriate time will often be a relief to her that the subject has been mentioned. Sometimes, closed questions (questions to which the reply is yes or no) are more useful to elicit information from the woman than are open questions, which may be misinterpreted. For example, the question, ‘Do you ever leak urine when you sneeze or during exercise?’ is very clear.

Sometimes, assessment may take place while casually talking about another topic or when performing a physical task. Selby (2005) refers to the ‘moment of truth’, when the woman identifies a moment when she is enabled to talk about her inner feelings, where intimacy and touch by the nurse are the releasing factors. Many nurses feel out of their depth discussing sexual matters, but often the patient just wants the opportunity to talk about her experiences and feelings.

Webb (1985) recommends that potentially threatening or embarrassing questions can be ‘unloaded’ by preceding them with a general statement such as, ‘Many people feel … how about you?’ Questioning methods like this prevent conveying assumptions about the patient. In this way, for example, when discussing surgery for a woman admitted for a vulvectomy, it may be helpful to ask, ‘Many women don’t like to feel inside their vagina or look at themselves down below, how do you feel about this?’

Shingleton and Orr (1987) recommended various questions to open up discussion of sexual anxieties following hysterectomy (Box 20.1). They provide an ideal framework to begin discussing any sexual concerns with women and can be adjusted to whichever operation an individual woman is having.

Box 20.1

Box 20.1 Questions to open up discussion of sexual anxieties following hysterectomy

• What does your uterus mean to you?

• How will hysterectomy change your life?

• What is the most important function of your uterus?

• What are your thoughts about losing your uterus?

Obviously, not all nurses are trained to perform vaginal examinations, but it is a skill with enormous benefits for the woman and the nurse. It may become a basis for a psychosexual nursing assessment without medical staff being present. Many continence and family planning nurses assess pelvic floor function while performing a vaginal examination, and it makes teaching pelvic floor exercises much easier (see p. 431).

The preadmission clinic provides an ideal opportunity for all these assessments to be undertaken by nursing staff. Unfortunately, due to the very busy nature and rapid turnover of most gynaecological wards, a nurse may only have 10–15 minutes to admit each patient, so the assessment must be straightforward and relatively quick.

The model of care based on activities of daily living developed by Roper, Logan and Tierney (2003) is frequently used as an assessment framework for planning care, since it is relatively easy to use. Often ‘standard’ care plans are used where the care required changes rapidly pre- and postoperatively, to plan care for discharge, and to identify areas where patient teaching is required. However, it is important that the psychological care of the individual woman and her family are also considered.

The primary goal of gynaecological nursing is to help the woman become independent and self-supporting (RCN, 1991). Orem’s Self-Care Model (1991) may therefore be more suitable for women with gynaecological conditions, since its central theme is patients taking responsibility for their health needs. The model promotes partnership between the woman and her nurse, and assumes the woman to be capable of making her own decisions regarding care.

Integrated care pathways are often used as the basis for planning the care of women admitted for specific procedures. However, nurses must still provide individualized nursing care, based on a holistic assessment that includes the woman’s perception of her own anatomy and physiology, with special attention to body image and sexuality.

Minor gynaecological surgery

Hysteroscopy, dilatation and curettage

Hysteroscopy, followed by dilatation of the cervix and curettage of the uterus (D&C), is still a common minor gynaecological procedure. It is now commonly performed in outpatient clinics, reducing the need for general anaesthetic.

A telescope is introduced into the endometrial cavity via the cervix, where the size and shape of the uterine cavity and the endometrium can be viewed directly.

This procedure is diagnostic where there has been occurrence of postmenopausal bleeding, postcoital bleeding (after sexual intercourse), or any instance of increased bleeding, both during menstruation and between periods (intermenstrual bleeding). It may reveal an endometrial polyp, or the pathology of the endometrial curettings may show an endometrial cancer.

Evacuation of retained products of conception

A D&C may also be used as a therapeutic intervention to treat heavy bleeding where the cause is retained products of conception following a miscarriage. This procedure is known as evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC).

A miscarriage may be described as the expulsion of the fetus from the uterus before it is viable, i.e. before it is capable of independent existence. This is considered to be before 24 weeks’ gestation. The correct medical term for a miscarriage is spontaneous abortion, but this can cause additional distress to women, so the term miscarriage is preferred.

The cervix is gently dilated and a curette (spoon-like instrument) is used to scrape away the lining of the uterine cavity. The procedure only takes a few minutes, and the cervix closes naturally afterwards.

The language used when caring for women who have miscarried is always important. It is advisable that the procedure is not referred to as a ‘scrape’, since this can understandably upset mothers. Women are particularly vulnerable at this time and appreciate health professionals recognizing their loss as significant and as a real baby rather than a fetus.

Women not only need physical and emotional support at this time but also require information to be given clearly, honestly and in a sensitive manner. Evacuations of retained products of conception are often performed at the end of a booked theatre list, as they are not considered a priority compared with other emergency cases, e.g. trauma, and consequently women may have to wait several hours for surgery. This can further add to their distress, particularly when they have not been allowed to eat or drink and the nursing staff cannot confirm when the operation will be performed.

Surgical treatment is one of three options the woman should be counselled about, so she can make an informed decision. The other options are conservative or medical treatment.

• Conservative management – this should only be offered if the woman is not bleeding heavily. Nature is allowed to take its course and a spontaneous miscarriage occurs. A full explanation must be given of what the woman should expect in terms of pain, bleeding and the expected appearance of the products of conception. She must be given contact phone numbers for the hospital in case the bleeding or pain becomes excessive. A scan is arranged for up to 1 week later, to assess for retained products of conception. This is a natural option and offers women the opportunity of being in control of their bodies with an alternative to medical or surgical treatment. However, some women cannot cope with the psychological effects of carrying a dead baby for possibly several weeks; for these women, one of the other alternatives may be more appropriate.

• Medical management – this has developed over recent years and has been shown to be extremely effective. The woman is given combination treatment with the antiprogesterone mifepristone, and prostaglandin E – either orally, such as misoprostol, or vaginally, such as gemeprost (RCOG, 2006). The first dose – i.e. mifepristone – is usually given to the woman while in the early pregnancy assessment unit, and she returns to the ward for completion, using misoprostol 36–48 hours later. The woman must be counselled fully about the effects of the treatment, i.e. that she will have some bleeding and may even miscarry at home. Any products passed must be examined closely for fetal, membranes and placental tissue, to ensure there are no retained products. The woman must be able to return to the hospital at any time should she start to miscarry before the second dose. An advantage of this treatment is that the woman does not require a general anaesthetic, but she will have to experience a process similar to labour during the expulsion of the products.

Loss of a pregnancy, for whatever reason, i.e. miscarriage, stillbirth, ectopic pregnancy or even termination of pregnancy, can cause psychological problems for the woman and her partner for some time after the event. Miscarriage may create problems with a woman’s self-concept, inner feelings of failure, loss of faith in her body, and other conflicts in the marriage and family relationships. Guilt is a common feeling and it may take a sympathetic partner and skilled nursing care to help a woman at this time. However, the psychological impact on fathers is often overlooked.

Touch is a powerful healer. Yet, bereaved parents may be unable to touch each other in sexual intimacy. It may take time and emotional resolution for a woman to feel healed and ready for sexual contact. Some couples may shy away from lovemaking in order to avoid intercourse and the memory of the dead child’s conception. Others may be terribly fearful of another pregnancy too soon, and be unwilling to trust contraception. Hidden agendas – including unexpressed thoughts, feelings or issues – never remain hidden for long in couples who know each other well. They show up in body language and touch, and, by discussing fears and needs, couples may be released from their tensions, so that physical contact can be fully enjoyed again.

A couple who have had a miscarriage should be advised to wait until the woman has had one normal period before trying for another pregnancy. Obviously, this is often the last thing the couple want to do, and it is very crucial that nurses do not assume the attitude, ‘Go home and get pregnant again’. The nurse must be aware of all the psychological aspects mentioned above, to ensure they are empathetic and supportive to both parents.

Termination of pregnancy

A similar procedure is also used to perform an early suction termination of pregnancy (STOP) during the first trimester – up to around 12 weeks’ gestation (Campbell and Monga, 2006). The cervical canal is dilated to take the aspiration cannula, the size used depending on how far the pregnancy has advanced. The vacuum is switched on and the products of conception are dislodged and aspirated. A small curette is then used to check the completeness of the evacuation. The pregnant uterus is obviously enlarged and more vascular, so the risk of uterine perforation and the risk of need for a re-evacuation if not all the products of conception are removed should be explained fully. These procedures are usually performed as day cases under general anaesthesia, but some hospitals do offer the option of a local anaesthetic, which reduces waiting times.

Laparoscopic surgery

Laparoscopic adhesiolysis or salpingolysis

This operation is performed via the laparoscope and consists of dividing the peritubal adhesions around the upper ends of the Fallopian tubes. If the fimbriae are not damaged and the adhesions are not too extensive, the lining epithelium of the Fallopian tubes is likely to be intact and its function may be restored. Campbell and Monga (2006) state that 30–50% of patients could become pregnant up to 6 months following surgery but that ectopic pregnancy occurs in up to 5% of these patients.

Laparoscopic treatment for endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition which occurs in women of reproductive age where endometrial tissue (that usually lines the uterus) is found outside the uterus. If it is confined to the myometrium, it is called adenomyosis. Endometriosis may be found on the ovary, broad ligament, bowel and bladder and occasionally has been seen in the lung. In severe endometriosis, the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, uterus and bowel are stuck together by dense adhesions.

The range of symptoms and pain experienced by different women vary considerably. During menstruation, the endometrial tissue is subject to the same hormonal changes as the uterus. The blood released has no way of escape and is reabsorbed into the bloodstream. The inflammation caused gives rise to scarring and adhesions. The deposits may be seen as tiny black spots or as larger cysts, known as ‘chocolate cysts’, from the appearance of altered blood. This condition can be treated surgically under the enhanced vision of the laparoscope by destroying the tissue by diathermy or, if the deposits are large enough, by surgically cutting them out and removing them. Risks associated with this surgery include damage to bowel or bladder, often due to adhesions of organs caused as a result of the endometriosis.

Laparoscopic treatment for polycystic ovarian disease

Therapeutic laparoscopy may also be used to treat polycystic ovarian disease. This condition occurs when the ovaries are enlarged and contain numerous cystic follicles. The normal production of oestrogen is affected, resulting in absence of periods (amenorrhoea) or irregular periods (oligomenorrhoea). A woman is considered to have polycystic ovarian syndrome when she has other symptoms in addition to the cysts on the ovaries, such as acne, hirsutism, weight gain, pelvic pain and infertility.

During laparoscopy, multiple holes are made in the ovary, causing drainage of the subcapsular cysts, which contain high levels of androstenedione. This will lead to a rise in FSH secretion, and, ultimately, spontaneous ovulation should occur. Where ovulation does not occur spontaneously, women often respond to clomifene, even where they were resistant to it before surgery. Although the effect is usually temporary, it allows ‘a window of opportunity’ for women to attempt conception without having to resort to other, more expensive, infertility options.

Laparoscopic sterilization

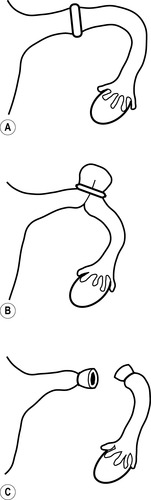

Female sterilization involves the blocking or excision of the Fallopian tubes, thereby preventing the ovum from meeting the sperm and fertilization taking place. The various methods of blocking the tubes are shown in Figure 20.2.

|

| Figure 20.2 • Female sterilization techniques: (A) Filshie clip; (B) Fallope ring; (C) tying of ends after the tube has been cut. |

The majority of sterilizations are performed laparoscopically. Occasionally, a mini-laparotomy (8–10-cm scar) may be necessary if access and visualization of the Fallopian tubes is difficult. This may be due to the woman being obese and/or she has had previous pelvic surgery, or she has had infections which have resulted in multiple adhesions. In this instance, a stay in hospital of 1 or 2 days will be recommended and heavy lifting should be avoided for about 3 weeks.

Pregnancy following this operation is rare – 1 in 200 operations (RCOG, 2004) – but if it does occur there is usually a higher risk of an ectopic pregnancy (Campbell and Monga, 2006). The woman must also be warned of the risk during laparoscopy of damage to adjacent organs or vessels, and advice should be given about pelvic and shoulder tip pain that can develop following laparoscopy.

It is not advisable to carry out sterilization at the same time as a termination of pregnancy, because of the vascularity of the tissues involved, or after delivery by caesarean section, where the uterus may be large and the tubes high in the abdomen. The woman must consider this operation to be irreversible.

A new technique developed is hysteroscopic sterilization. This involves the introduction of a small device at the opening of each tube at the junction with the uterus under hysteroscopic view. It can be done in an outpatient setting under local anaesthetic or intravenous sedation, and so the woman does not have to have a general anaesthetic and is fit to go home after only a few hours. Close audit of complications and outcomes is advised by NICE (2004a) as there are no long-term data available yet of its efficacy.

Nursing care for minor gynaecological and laparoscopic surgery

Preoperative care

Preoperative care and information is a vital part of the preparation of a woman who is to undergo any gynaecological operation, whether minor or major. This is particularly true of women experiencing a miscarriage or termination. A miscarriage is a problem which occurs suddenly. The woman is admitted to hospital quickly, without time to make plans for the care of any other children. It is important to consider the feelings of both partners and ensure family members have a direct telephone number to the ward. For more detail, please see Chapter 4.

Most minor gynaecological procedures are carried out as a day case, although increasingly procedures are being undertaken in the outpatient setting. The nurse must ensure the woman feels relaxed and not part of a conveyor belt, by appearing unhurried and focused on the woman.

Postoperative care

Women usually recover very quickly from minor investigations and operations. Providing their observations are stable and vaginal bleeding is not heavy, they may be escorted to the lavatory to pass urine. Once they have tolerated fluids and a light diet, they may go home, usually a minimum of 4 hours after their anaesthetic.

It is important that a partner or friend collects the woman following day surgery, and a written information leaflet containing discharge advice and a contact telephone number should be given to her.

Discharge advice

• It is common to have some bleeding after the procedure, which may be bright red at first and should gradually decrease to a brownish stain.

• The woman should be accompanied home and overnight in case of complications developing.

• Sanitary towels rather than tampons should be used, to reduce the risk of infection.

• Mild painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen may be used to relieve any pain.

• It is advisable for the woman to take a few days off work and resume a normal lifestyle and work when she feels ready.

Specific advice following an evacuation of retained products of conception or a suction termination of pregnancy

The advice for women following these two procedures is similar to that for a dilatation and curettage.

• Breast tenderness may be a problem, especially if the miscarriage or termination occurred later in the pregnancy. Women should be warned about this, since it can be a distressing symptom. A well-supporting bra will help reduce discomfort, but it is not usually necessary to take any medication.

• Following a termination, it is crucial that women are offered comprehensive contraceptive advice. They may begin taking the oral contraceptive pill the evening of the operation or the following morning. They should return to their GP 6 weeks after the operation for a general check-up and further contraceptive prescriptions.

• A follow-up hospital appointment is not usually offered unless the woman has had three consecutive miscarriages, or has a miscarriage in the second trimester of pregnancy.

• The Miscarriage Association and SAFTA (Support after Termination for Abnormality) have a useful range of booklets.

• Some hospitals have their own Miscarriage Group run by a bereavement counsellor, and many have an annual remembrance service for all the babies who have died before or at birth in the previous year.

In Table 20.1, Table 20.2 and Table 20.3 a care plan details Roper’s Activities of Living for Jean, a 30 year-old woman who has lost her baby through a miscarriage and is to undergo an evacuation of retained products of conception. Jean was 10 weeks’ pregnant and had recently had her first scan. Last night she began to have mild backache and found she was bleeding from her vagina. Her 5 year-old son David had accompanied her when she had her first scan.

| Activity of living | Assessment baseline |

|---|---|

| Maintaining a safe environment | Baseline observations: – Pulse 84 bpm – Respiration 18 rpm – Blood pressure 100/60 mmHg – Weight 64 kg Blood loss per vagina: moderate to heavy No known allergies |

| Communication | Would like to be known as Jean Very anxious and tearful at present |

| Breathing | Tendency to hyperventilate when anxious Non-smoker |

| Eating and drinking | Vegetarian diet |

| Elimination | Bowels: BO twice daily – constipation during pregnancy Haemorrhoids during last pregnancy Bladder: – Urinary frequency – Urinalysis NAD |

| Personal cleansing and dressing | Daily shower |

| Controlling body temperature | Temperature 37°C |

| Mobilizing | Fully mobile Plays badminton twice a week Not at risk of pressure ulcer since Jean can move around the bed |

| Working and playing | Full-time solicitor Nanny looks after son Enjoys patchwork making and reading |

| Expressing sexuality | Married with one son aged 5 Husband accompanied Jean on admission LMP 16.3.08 K–4–5/28–30 Contraception: condom G3, P1 Baby Christopher died aged 2 days in October 2006 Last smear October 2007 Checks breasts when she remembers |

| Sleeping | Usually 6–7 hours/night |

| Activity of living | Problem | Aim | Nursing care | Rationale | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicating | Anxiety due to hospitalization | To ensure Jean is as calm and relaxed as is possible | Jean has one nurse to look after her as far as possible Approach Jean in a calm friendly manner Explain all nursing care and procedures to Jean Allow Jean to ask questions Encourage Jean to verbalize her anxieties | The woman can establish a meaningful relationship with her nurse | Jean is tearful and worried about her 5 year-old son, David. The hospital reminds her of Christopher’s death and all that it entailed |

| Pain due to uterine contraction | To ensure Jean is pain-free, or feels in control of any pain she may experience | Offer analgesics as prescribed Observe for effectiveness 20–30 minutes later Check for non-verbal signs of pain Position comfortably in bed Encourage Jean to tell nurse of any pain she has | Jean has refused analgesics and states her pain is not unbearable. She wants to ‘suffer pain for her baby as it suffered’ | ||

| Maintaining a safe environment | Bleeding due to miscarriage | To detect excessive blood loss | Observe Jean’s vaginal loss ½ hourly If very heavy (i.e. 1 sanitary towel/½ h), save pads and any tissue passed for review | To monitor uterine haemorrhage | Jean’s blood loss is moderate to heavy |

| Lack of preparation for theatre | Jean is adequately prepared for theatre | Record vital signs, pulse, temperature, respirations, blood pressure | To establish a baseline for postoperative observation | Pulse 84 bpm Temp 37°C Respiration 18 rpm BP 100/60 mmHg | |

| Ensure Jean has removed all her make-up and nail varnish | Make-up obscures cyanosis, and nail beds are used to ensure adequate tissue perfusion | ||||

| Ensure Jean has removed all her jewellery except her wedding ring | To prevent diathermy burns from static electricity | ||||

| Check that the consent form has been signed | Legal requirement | ||||

| Eating and drinking | Lack of preparation for theatre | Jean is fasted for 4–6 hours before surgery | Explain to Jean why she cannot eat or drink

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|