17. Patients requiring colorectal and anal surgery

Fiona Hibberts

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Investigations325

Colorectal and anal disorders327

Enhanced recovery following colorectal surgery345

At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to:

• describe the anatomy and physiology of the lower gastrointestinal tract

• briefly explain specific investigations for patients with colorectal and anal disorders

• briefly explain causes, conditions and surgical interventions

• give examples of assessment procedures for patients undergoing colorectal and anal surgery

• highlight specific pre- and postoperative management

• assist in the education and discharge planning of patients.

Introduction

This chapter will provide information for nurses who are caring for patients on a surgical ward that specializes in colorectal and anal surgery. It will focus on surgical interventions that are carried out when all other methods of treatment have been ineffective or are, indeed, inappropriate. This chapter will also include endoscopic practice, and both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures will be outlined.

There are many different techniques and practices in the field of gastroenterology; therefore, surgical procedures may have slightly different names, according to their origin. It is important to use this book in conjunction with current evidence-based practice and research.

For the purpose of this chapter, the assessment framework is based on the Roper, Logan and Tierney model of nursing, as described in Holland et al., 2004 and Holloway, 1993 care planning, as this remains best practice in the ward environment. The generalized pre- and postoperative management remains the same as for any patient undergoing colorectal and anal surgery, and only specific problems will be highlighted following discussion of the disease or organ dysfunction.

Investigations

There are many investigative procedures that a patient may undergo in order to diagnose the disorder and enable the surgical team to plan the relevant course of action or surgical intervention (Table 17.1). It is often a process of elimination by considering differential diagnoses.

| Investigation | Surgery |

|---|---|

| Abdominal X-rays | GI tract |

| CT scan | GI tract |

| Barium enema | Lower GI tract |

| Colonoscopy | Lower GI tract |

| Sigmoidoscopy | Lower GI tract |

| Proctoscopy | Lower GI tract |

| Ultrasound | Abdomen and GI tract |

| Proctography | Lower GI tract |

| Transit study | Lower GI tract |

The patient requires a full explanation of the proposed investigation, in order to make an informed decision about whether to go ahead with the test or not. Patients will be required to give verbal and often written consent. Informed consent will involve a discussion with the patient, outlining what the test will look at specifically, the risks involved and the potential outcomes of the test, and, indeed, not having the test at all. The Department of Health provides guidance for consent in their document Good Practice in Consent (DoH, 2001). The most common investigations are briefly described below.

Abdominal X-rays

Under normal circumstances, dense material may be penetrated by X-rays which give an outline of the organs or bones under investigation. When investigating soft tissue and organs of the abdominal cavity, it is often necessary to use a contrast medium such as barium sulphate, to highlight the spaces and cavities in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. X-rays use ionizing radiation and therefore carry a degree of risk, particularly during rapid cell division in the early stages of pregnancy.

Abdominal X-rays are useful in detecting abdominal fluid levels, bowel gas, constipation and obstruction.

Nursing issues

The patients most at risk from this procedure are female patients during their reproductive life, as there is an increased possibility of affecting a fetus through pelvic X-rays. Consequently, any abdominal or pelvic radiography should be carefully monitored and only carried out if absolutely essential. A 10-day rule applies to all radiological examinations of the lower abdomen for female patients of reproductive age: i.e. the examination is to be carried out within 10 days following the first day of the last menstrual cycle. There may be some exceptions to this rule for those women who have been sterilized, are menstruating, or are not sexually active.

CAT (computerized axial tomography)/CT scan

This scan provides a computerized picture of a part of the body, which is achieved by combining fine X-rays, often with a contrast medium. ‘Slices’ of the abdomen are produced and are useful for detecting irregular anatomy, including tumours.

Barium studies

A radio-opaque contrast medium called barium sulphate is used for radiological studies of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a fine, milky contrast medium that can be taken orally or given rectally, to allow detection of small alterations in the small bowel, colonic and rectal mucosa.

Barium enema

Barium sulphate is introduced into the rectum and retained by the patient while radiological studies are undertaken to detect disorders of the rectum and large intestine. It is particularly useful in diagnosing diverticular disease, strictures, obstruction, polyps and tumours, but is contraindicated where there is a fistula present or potential risk of perforating the bowel.

Nursing issues

When barium is used for radiological studies in the rectum, special attention should be paid to ensure that the rectum is emptied prior to the procedure, and that constipation following the procedure is avoided by increasing fluid intake, and removing the contrast medium by a cleansing enema.

Proctogram

Barium sulphate paste is introduced into the rectum and the patient is given barium sulphate to drink. This will highlight the presence of an enterocele, rectocele and any anatomical disorder of the rectum.

Transit studies

In order to investigate the amount of time food takes to work its way through the gastrointestinal tract, radio-opaque markers in capsules are given to the patient and swallowed. After 5 days, a plain abdominal X-ray is taken and the markers can be traced. Slow gut transit, resulting in constipation, can be diagnosed.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, proctoscopy

The cavities or interior of the gastrointestinal tract can be investigated through the use of an endoscope, which is a luminous fibreoptic instrument that can be inserted via the rectum for viewing internal organs, then relaying them to a television screen. The fibreoptic endoscope is often used to reach areas previously inaccessible with other instruments, as it has greater flexibility. Instruments can also be passed through the special tube of the endoscope, to obtain biopsies or perform other procedures such as polypectomy.

For this investigation to be successful, the bowel should be clear. Therefore, an enema, aperient or suppositories may be given to remove faecal contents. More commonly, one or two sachets of bowel preparation may be given prior to the investigation. This procedure is usually performed to detect any abnormalities of the colon, investigate rectal bleeding, changes in bowel pattern, anaemia or the cause of an obstruction, e.g. a cancer.

Nursing issues

Cleansing of the lower colon may be contraindicated in lower rectal carcinoma and colonic inflammatory disease. After the tests, the patient may feel uncomfortable, with a bloated sensation, associated wind pains and, occasionally, nausea.

Stool specimens

These are usually obtained and cultured to detect infective organisms, occult bloods or faecal fats collection. The stool specimen may be a single sample or be part of a series of specimens.

Colorectal and anal disorders

Small intestine

Anatomy and physiology

The small intestine is a long, muscular, tubular organ which runs from the pylorus through to the caecum, terminating at the ileocaecal valve. It consists of the same layers as throughout the intestinal canal, which have been described in detail on page 305. However, the submucosa and mucosa differ, as their main function is to absorb and assist in the final stages of digestion. The small intestine is divided into three main sections – the duodenum, jejunum and ileum – and is approximately 2.5 cm in diameter, and approximately 3–8 m in length.

The mucosal layer has an increased surface area created by folds and villi that help in the absorption of intestinal contents. In between the villi are small pits lined with glandular epithelium, referred to as glands or crypts (crypts of Lieberkühn), their main function being the secretion of intestinal digestive enzymes.

These digestive enzymes leave the intestinal walls vulnerable to enzymatic action. Therefore, the walls of the small intestine are protected by alkaline secretions from Brunner’s glands in the duodenum, and mucus throughout the small intestine which have the effect of neutralizing the acid and enzymes.

Normal function

Food is propelled along the small intestine by peristalsis. This action involves muscular activity by rhythmic, relaxing and propulsive movement. These actions allow the food to be mixed and broken down for absorption and move the chyme through the small intestine. Intestinal juices are secreted to assist in the digestion of carbohydrates and proteins. Fats are converted into fatty acids and monoglycerides by the action of pancreatic lipase. Bile salts then assist in converting them into a water-soluble form, for absorption by the villi. The small intestine is responsible for absorbing approximately 90% of the nutrients through the villi by a variety of processes. This is facilitated by the secretion of enzymes, particularly the pancreatic enzymes, amylase and protease, that chemically assist the breakdown of food into smaller molecules.

Abnormal function

Increased peristalsis may cause colic and diarrhoea, which can result in the malabsorption of nutrients. Sometimes, abdominal surgery causes a paralytic ileus, thereby preventing the passage of food and reducing the absorption of nutrients.

Small bowel obstruction

Intestinal obstruction refers to the blockage or slowing down of the normal flow of intestinal contents and may be partial or complete (Table 17.2). The intestine above the blockage becomes dilated, and secretions accumulate, causing stagnation of the contents or even reverse flow. The involved area collapses and loses its function. The intestinal contents build up as the bowel dilates and can cause vomiting, often faeculent in nature. Over half of small bowel obstructions are said to be caused by adhesions. Other causes are hernias, diverticular disease and cancer of the large intestine.

| Cause | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Mechanical – blockage of the lumen | |

| Foreign body | Laparotomy, excision and removal, repair |

| Mechanical – lumen wall altered by disease | |

| Crohn’s disease – strictures | Small bowel resection or strictureplasty |

| Intussusception | Reduction or resection and anastomosis |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | Reduction, repair or resection |

| Volvulus | Small bowel resection |

| Neoplasms | Resection, excision of tumour and end-to-end anastomosis |

| Mechanical – occurring outside the lumen | |

| Strangulated hernia | Reduction and repair or resection |

| Adhesions | Division of adhesions |

| Neoplasm | Resection, excision of tumour and end-to-end anastomosis |

| Paralytic | |

| Previous surgery | Decompression by nasogastric intubation |

| Infection | Withhold all food and fluid; antibiotics |

| Mesenteric ischaemia | Surgical resection and anastomosis |

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations depend on the degree of obstruction and portion involved, but, in acute small bowel obstruction, present as sudden onset, associated with severe symptoms of colicky pain, nausea, vomiting and dehydration, resulting in loss of electrolytes. Often the blockage can be complicated by interference with the blood supply to a section of small intestine, which may result in ischaemia, tissue necrosis and the threat of perforation. This type of obstruction requires immediate surgical intervention. Clinical manifestations of chronic or subacute small bowel obstruction present with a slower onset, as the lumen gradually obstructs. Symptoms progressively become worse as the condition develops. This type of obstruction will require surgery, but is less urgent in nature.

Small bowel obstruction is often referred to as either mechanical or paralytic and may be diagnosed by observing for clinical manifestations, particularly vomiting faeculent fluid, absence of faeces, colicky pain and abdominal distension.

Diagnosis

A detailed history, abdominal examination and abdominal X-rays are often all that is required.

Mechanical obstruction

Mechanical obstruction can occur anywhere in the small intestine and may be simple in nature or complicated by strangulation. This type of obstruction arises from either an internal blockage that occludes the lumen, or external pressure to the lumen of the bowel.

Foreign body

This type of obstruction is rare and can be due to gallstones or a food bolus that has not been digested and remains lodged in the small intestine, causing a blockage. Intervention is by surgical laparotomy to deal with the underlying cause.

Crohn’s disease strictures

The formation of scar tissue as a result of frequent exacerbation of the disease results in narrowing of the lumen of the small intestine. Intervention is by small bowel resection, strictureplasty or, if accessible, by endoscopic dilatation.

Intussusception

This is caused by telescoping of the intestine, often very close to the ileocaecal valve, and occurs frequently in young infants. One portion of the bowel prolapses into the lumen of another portion. Specific clinical manifestations include those already described, but it may also present with blood in the stools. Diagnostic investigations include barium enema. Intervention is by reduction, resection and anastomosis of the bowel.

Meckel’s diverticulum

This a congenital condition where there is incomplete closure of the yellow stalk, a duct that links the yellow sac with the midgut of the embryo, leaving a sac which protrudes from the wall of the ileum. Its length can vary from 2 to 50 cm, and it is susceptible to inflammation. It is often asymptomatic, but it may present similarly to appendicitis, or intestinal obstruction. Intervention is by surgical resection of the affected part of the bowel.

Volvulus

This is a twisting of the small bowel, occurring more commonly in the ileum, but it can also occur in the caecum or sigmoid colon. It can lead to ischaemia, necrosis, perforation and peritonitis if not corrected. Specific clinical manifestations include nausea, vomiting, severe colicky pain and absence of bowel sounds. The abdomen is distended and rigid due to the accumulation of gas and fluid that has become trapped. Diagnosis is by abdominal X-ray. Intervention is usually by surgery, but endoscopic decompression may be enough for a caecal or sigmoid volvulus.

Neoplasms

New growth of tissue (tumour) may be benign or malignant. Diagnosis may be by barium radiological studies, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, proctoscopy and stool specimens for occult blood. Intervention is by resection, excision of the tumour and anastomosis of the bowel, with or without a stoma. Further treatment may be necessary with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy.

Strangulated hernia

This is a weakness in the muscle wall which allows peritoneum and bowel to protrude. It is irreducible and becomes constricted, therefore reducing the blood supply and causing ischaemia, necrosis and gangrene of the contained omentum or loop of bowel. Clinical manifestations also include colicky pain and increased swelling of the herniation. Diagnosis is by abdominal examination and X-ray. Intervention is by reduction and repair, or resection of bowel.

Adhesions

These result from formation of scar tissue within the peritoneal cavity. This usually occurs during the inflammatory response of healing, when tissue becomes attached to part of the intestine. It is associated with previous surgery, presence of infection, inflammation or injury. Clinical manifestations result when the intestine becomes twisted or kinked; they depend on the degree of obstruction but generally include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramp pain and distension. Diagnosis is by abdominal X-ray. Intervention is by dividing the adhesions to free the intestine if the obstruction does not settle with conservative management.

Paralytic obstruction (paralytic ileus)

This condition is an absence or decrease in peristaltic action, which results in bowel contents not flowing efficiently through the small intestine. Although not strictly a specific complication, it is appropriate to mention it at this point, as the condition is associated with abdominal surgery, infection or mesenteric ischaemia. Clinical manifestations include those already discussed but may be complicated by fever, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and respiratory distress. Diagnosis is by abdominal examination and abdominal X-ray. Intervention includes symptomatic management.

Nursing intervention

Many patients admitted with small bowel obstruction are treated as surgical emergencies, therefore time to improve nutritional and fluid levels is restricted. Fluids lost through vomiting or diarrhoea should be replaced and electrolytes corrected by intravenous infusion. The patient should be encouraged to rest and abstain from taking food or fluids orally until bowel function returns. A nasogastric tube on continuous drainage and intermittent suction is usually inserted to allow decompression of the bowel. Vital signs are monitored and pain control management evaluated.

Occasionally, surgical intervention, e.g. laparotomy with or without resection, and with either anastomosis or stoma, is required if the paralytic ileus results in a complication such as ischaemia or perforation.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease usually refers to two disorders – Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – although there are other forms.

Crohn’s disease

Otherwise known as regional ileitis or granulomatous enteritis, this subacute and chronic inflammatory disorder was identified in 1932 by the American physician Burrill B. Crohn. The disease is often considered together with ulcerative colitis; however, it has a different aetiology and clinically presents differently. It can affect any part of the digestive system, but is common in the small intestine, particularly the terminal ileum. The diseased segments are often separated by normal bowel segments and can appear as isolated ‘skip’ lesions in other parts of the intestine. The inflammation may cause excessive production of fibroblasts and angiogenesis, i.e. new capillary buds, and is histologically distinguishable by the formation of a granuloma. Clinically, there is a thickening of the bowel wall and mucosal lining, giving a cobblestone appearance at the advanced stage. There is also a danger of the affected section of bowel forming abscesses that may rupture, or narrowing of the lumen through fibrosis and transmural damage, causing fistulae or sinuses (Cuschieri et al, 2002).

Crohn’s disease is particularly common in young adults, although it can occur at any age and in both sexes equally, and in developed countries, with higher frequency in whites and the Jewish population. The incidence is thought to be higher than recorded, because many people remain undiagnosed (Harrison, 1984). There is still much speculation as to the cause of the disease, but, like many other disorders, it is multifactorial, with genetic and environmental factors. Many genes have been identified and it can be associated with autoimmune disorders, food additives, allergens and individual response to stress (Cuschieri et al, 2002).

Clinical manifestations

Clinical symptoms of the disease are insidious and often well advanced before the patient seeks help. The patient may present to the doctor complaining of tiredness associated with lethargy and sometimes a persistent elevated temperature.

Other specific symptoms include abdominal pain that is often described as similar to cramp, particularly after meals. This is the result of peristalsis following the intake of food, and the inability of the contents to flow through the narrowed lumen. Some patients will complain of chronic mild pain which is persistent in nature, occurring between the cramping spasms, and some may have a painful and ineffective desire to empty the rectum (tenesmus). Chronic inflammation of parts of the intestine and oedema may result in diarrhoea. The patient will often admit to having lost weight as a result of withholding food to avoid the cramping pain. This may lead to malnutrition and anaemia, as the patient may already be malnourished due to malabsorption of nutrients through the small intestine. Diagnosis is through patient history, physical examination, barium and radiological studies, colonoscopy and ileoscopy, blood (leucocytosis), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), haemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and stool specimens for infective organisms, fat content and occult blood.

Complications

Complications may arise due to obstruction, perforation, malabsorption, melaena due to bleeding ulceration, and the formation of abscesses. Other effects of the disease may present as skin ulceration and infection, iritis, arthropathy, and perianal sepsis in the form of anal fistulae.

Intervention

The vast majority of patients are treated medically, long term, with 5-ASA (5-aminosalicylic acid) compounds, steroids, and immunosuppressants such as azathioprine. Up to 70% of patients will, however, at some point in their life require surgical intervention. This may include segmental resection of small bowel, subtotal colectomy or total colectomy with formation of an ileostomy, or surgery for perianal disease. Patients may require surgery on many separate occasions (more than 50% in an attempt to ease symptoms of the disease).

Ulcerative colitis

This term is used to describe diffuse inflammation and multiple ulcerations of the superficial mucosa and occasionally the submucosa of the large intestine and rectum. The mucosa becomes oedematous and reddened with bleeding, and eventually becomes ulcerated. This ulceration results in the large intestine developing numerous continuous lesions that eventually cause muscular hypertrophy, which will shorten, narrow and thicken the bowel. The patient will have periods of exacerbation and remission. There is a danger of toxic dilatation, especially in the transverse colon in severe acute disease, which may result in perforation (Donnelly, 2003).

Aetiology and incidence

This is generally unknown but is similar to Crohn’s disease. Some personality traits may influence the progression of ulcerative colitis, e.g. individuals who often present as passive and dependent personalities and are anxious to please (Whitehead and Schuster, 1985). Consequently, they find it more difficult to cope and may become psychologically, physically and emotionally stressed. Stress and emotional disturbance may influence the blood supply to the colon, which may result in eventual ulceration. Ulcerative colitis has also been associated with an immunological response to antigens (Mahilda, 1987).

As in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis has a familial tendency (Mahilda, 1987), and commonly affects young adults to the middle-aged (Day, 2003, Goligher et al., 1980 and Morson et al., 1979). Other conditions such as arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, pyoderma gangrenosum and hepatitis may be associated with ulcerative colitis (Kelly, 1994).

Clinical manifestations

These are similar to those described in Crohn’s disease but, histologically, crypt abscesses are seen, which can become necrotic and ulcerated. There is intermittent tenesmus with urgency and cramping pain. Loose bowel action may occur, often 10–20 times daily. Rectal bleeding may be present, sometimes with anaemia. Eventually, the debilitating progression of the disease may extend to such a degree that it affects normal activities of daily living and social interactions. It can also be so advanced that fistulae and abscesses may be present.

Diagnosis is by barium radiological studies and blood tests, which may identify a high white blood count (WBC), platelets and ESR. Colonoscopy is the diagnostic tool of choice; however, there are some reservations on performing the procedure on patients who have active colitis, due to an increased risk of perforating the bowel (Hardman et al, 1995).

Intervention

If medical intervention and control with 5-ASA compounds and steroids does not bring about remission, or the disease has been active for the most part of 20 years, the patient may have an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum, and surgery is then advisable. Emergency life-threatening complications usually require surgical intervention.

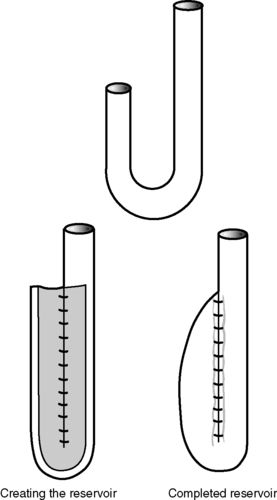

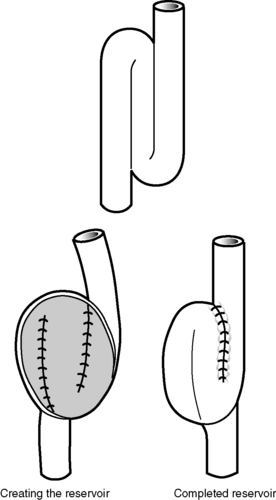

Surgical intervention may include subtotal colectomy and ileostomy, or either proctocolectomy with formation of an ileostomy or ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis (Table 17.3). The pioneer in this field was Sir Alan Parks, who developed the Parks’ pouch procedure in the late 1970s (Parks and Percy, 1982). The main types of pouch are the J pouch, where the ileum is folded once into a ‘J’-shaped reservoir, then sutured directly to the anal canal, the S Pouch, which has three sections and the W pouch, which has four sections similarly joined to make a pouch and then sutured to the anal canal (Cuschieri et al, 2002) (Figs 17.1 and 17.2).

| Cause | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | Segmental resection Subtotal colectomy Total colectomy Strictureplasty |

| Ulcerative colitis | Kock’s pouch Parks’ pouch Proctocolectomy Total colectomy |

|

| Figure 17.1 • Ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis – J pouch (two sections of small bowel to form the pouch). |

|

| Figure 17.2 • Ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis – S pouch (three sections of small bowel to form the pouch). |

With increasing specialization in recent years, this type of surgical intervention has become more favoured over the traditional procedure of proctocolectomy and formation of an ileostomy. The purpose of ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis is to restore the continuity of the gastrointestinal tract and to promote acceptability, especially in younger patients, by preserving sphincter control and promoting continence (Wiltz et al, 1991). The implications of formation of an ileostomy are well documented, especially the psychological aspects associated with an altered body image (Black, 2000). An attempt is made to preserve the anal sphincter and provide an ileal–anal reservoir by resecting the colon and most of the rectum. The remaining rectum has the mucosa excised, leaving the sphincter muscles around the anus intact. A reservoir or pouch is constructed by using the lower part of the small bowel and is joined to the anus. Alternatively, a double-stapled pouch is formed and stapled to the upper anus without excising the mucosa. The bowel contents are usually diverted from the newly constructed reservoir by a temporary ileostomy, until it is healed. Approximately 2 months after the operation, healing is checked by a water-soluble contrast enema (pouchogram) and an examination under general anaesthetic. If healing is satisfactory and the anal sphincter muscles are sufficiently strong, the ileostomy is closed.

This whole procedure may be performed in three stages.

• Stage 1 includes the colectomy, preservation of the rectum and anal sphincter, and formation of ileostomy.

• Stage 2 includes the formation of the reservoir and loop ileostomy. This may be easily closed when the reservoir or pouch has healed. Stages 1 and 2 can be performed in one operation for elective cases.

• Stage 3 is closure of the loop ileostomy.

Ileostomy

In this operation, ileum is brought through an opening to the abdomen. It is usually performed following pan-proctocolectomy or total colectomy, when the diseased or inflamed bowel has been removed, e.g. in ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. The opening is higher up the bowel (ileum); therefore, bowel contents are more fluid, as the water has not been absorbed via the large colon.

Pre- and postoperative care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Specific preoperative assessment

If the patient has been in a period of exacerbation for some weeks, they may already be dehydrated and malnourished. Therefore, nursing intervention should include replacement of fluids and blood, and a nutritional support programme undertaken prior to surgical intervention; this may include total parenteral nutrition. If the patient is not in a state of exacerbation, then a low-residue diet is encouraged, with small portions several times a day. When steroid therapy has been a part of the previous management regimen, this is continued and sometimes larger doses are given at the time of surgery, and then slowly reduced over a period of time following surgery. Antibiotics are often prescribed as a prophylactic measure. In both types of surgery involving the formation of an ileostomy and ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis, psychological preparation and support from the stomatherapist should be an integral component of care planning.

The stomatherapist will also be involved in marking the site for the ileostomy, i.e. in siting it appropriately for the patient in terms of clothing, previous surgery and body fat distribution. Assessing the patient’s needs and matching these with the types of ileostomy appliances available is also important. A vital part of preparation for this type of surgery includes providing education and knowledge of the disease and surgical interventions in a language that the patient will understand and respond to by asking appropriate questions. There are many patient information leaflets available from organizations such as the Ileostomy Association of Great Britain and Ireland, and the British Colostomy Association, as well as the manufacturers of stoma products.

One of the problems that may arise with this type of surgery and formation of ileostomy is anxiety in the patient who feels that they may have lost control over faecal elimination, therefore increasing the risk of body image disturbance (Box 17.1).

Box 17.1

Box 17.1 Specific issues related to having a stoma

• Increased anxiety due to possible presence of odour and flatulence from the ileostomy.

• Increased anxiety associated with possible visibility of the stoma appliance through clothing.

• Anxiety associated with adapting to the ileostomy and ability to apply coping mechanisms.

• Anxiety regarding relationships with partners and expressing sexuality.

Specific objective will be to preserve the patient’s body image, and empower the patient in retaining sense of control over bowel function.

Nursing intervention and rationale

• The possibility of odour is one problem that causes considerable anxiety, and in order for the patient to control the odour, it is important that they change the bag regularly, and have knowledge of odour-proof bags and deodorants that are available for use when the bag is emptied and changed.

• Advice should be given on which types of food can be eaten that will reduce odour, e.g. orange juice and yogurt. Some foods should be avoided, such as cabbage, onions, beans and garlic, in order to avoid associated embarrassment of flatulence.

• The patient should be educated as to what foods may cause an increase in flatulence, and period of time between ingestion and production of flatus. If flatus is difficult to control, it can lead to increased social embarrassment.

• The patient should also be taught to anticipate the need for correct bag and deodorant filters to be attached, therefore minimizing the effects of flatus by releasing flatus through the deodorized filter.

• The patient should be educated as to how to conceal the bag underneath a stretchy layer of clothing. This will hold the bag next to the skin surface, thereby reducing the bulk. This will have the effect of enhancing body image by enabling the patient to dress acceptably in clothes that they already have.

• Discussion should be encouraged with the patient and family regarding the normal emotional response to an ileostomy. This gives the opportunity for negative feelings to be explored and accepted. Coping strategies should be addressed with the patient and their family, as these may need to be altered, adapted or new methods adopted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access