Chapter 3. Patient safety, litigation and complaints in the National Health Service

John Tingle

Every day over 1 million people are treated successfully in NHS acute, ambulance and mental health trusts (National Audit Office 2005). For the vast majority of patients, treatment and care goes smoothly and without incident. This care does take place in an increasingly complex health-care environment, an environment where good-quality and safe care is highly dependent on the successful interaction of professional skills, drugs and medical technologies. This is a complex interaction to try and manage as there are many variables and, given the necessary dependence on the human factor, it is always going to be inevitable that some mistakes will be made. Human beings do not always practise their skills to perfection. The challenge for nurses and other health carers today is to try to minimise the possibility of errors occurring by effectively managing risk and more broadly by helping to develop an ingrained NHS patient safety culture and also learning how to handle patient complaints properly.

In this chapter the topics of health-care litigation, patient safety initiatives and handling NHS complaints will be discussed. The role of nurses and others within the patient safety and complaints agenda will be identified.

PATIENT SAFETY: THE SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Nobody knows exactly how many patients are injured or killed in the NHS by nursing or medical accidents. It is only in relatively recent times that the NHS has started to count errors and has had the necessary infrastructure to do this with the advent of the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) run by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA). To date there have still been no major studies in the UK of the incidence and effects of patient safety adverse incidents in the NHS, although there are some smaller-scale studies and other indicators, which will be discussed later in this chapter. What we do know for certain is that patient safety is an acute problem in the NHS and enhancing patient safety has for some years been a central plank of government health policy, along with the development of NHS strategies to reduce patient complaints and clinical negligence claims. The first NHS organisations were connected to the NRLS in November 2003 and all NHS organisations have had the capacity to report incidents to the NRLS since December 2004. The NRLS is the first comprehensive compulsory national reporting system for patient safety incidents in the world.

The NPSA estimate the incidence of errors as follows: ‘On the best available data in England, extrapolating from a small study in two acute care trusts, it is estimated that around 10% of patients (900 000 using admission rates for 2002/3) admitted to NHS hospitals have experienced a patient safety incident and that up to half of these incidents could have been prevented’ (National Patient Safety Agency 2004).

In 2005 the NPSA provided the first public analysis of national patient safety data in England and Wales. Up until the end of March 2005, 85 342 patient safety incidents were reported. Most of these incidents (68% of the total) resulted in no harm to the patients. Of the reported incidents, about one in 100 led to severe harm or death. In acute hospital settings, about three in every 1000 reported incidents resulted in death:

Steps are being taken to deal with the issues identified in the reports and from other sources. The NPSA have developed an impressive armoury of publications and tools, which can be viewed from their website. A key NPSA publication is Seven steps to patient safety (National Patient Safety Agency 2004). The steps provide a simple checklist to help health-care staff plan their activity and measure performance. Following the steps will help ensure that the care provided is as safe as possible. The steps are:

The NPSA works from the premise that the best way of reducing error rates is to target the underlying systems failures.

“Based on incidents and deaths reported over a three month period by 18 trusts, the NPSA has estimated that each year there would be approximately 840 deaths and 572 000 incidents reported in acute trusts in England…. Further work is needed to arrive at a more precise figure. The most common types of incidents reported are patient accidents (in particular falls) and incidents associated with treatment, procedure and medication…. Insufficient communication, education or teamwork are associated with many of the reported patient safety incidents across all settings and types of incidents.

“1 Build a safety culture

Create a culture that is open and fair

2 Lead and support your staff

Establish a clear and strong focus on patient safety throughout your organisation

3 Integrate your risk management activity

Develop systems and processes to manage your risks and identify and assess things that could go wrong

4 Promote reporting

Ensure your staff can easily report incidents locally and nationally

5 Involve and communicate with patients and the public

Develop ways to communicate openly with and listen to patients

Encourage staff to use root cause analysis to learn how and why incidents happen

7 Implement solutions to prevent harm

Embed lessons through changes to practice, processes or systems

“For any system as complex as the NHS to achieve all of the above requires a significant shift in culture and a high level of commitment across the service over many years. We recognise that some NHS organisations are further down this path than others, and that you may need to prioritise the steps you take next.

Adjusting patient expectations

Patient expectations about what can be achieved in an NHS struggling to balance its books (Hawkes & Charter 2006) are today perhaps a tad unrealistic and a programme of re-education needs to take place. As we have seen, government policy has been directed towards making the NHS revolve around the interests of the patient; perhaps it is now time for a new strategy – a strategy directed towards viewing patients as equal or equity partners in a common enterprise. Partners have responsibilities and cannot simply function, as some patients do, just as vitriolic recipients of care. The NHS is becoming a safer place as a developed patient safety infrastructure is being slotted into place, although it must be acknowledged that we are still a long way off from developing an ingrained patient safety culture. Only incremental progress is being made. The National Audit Office state (NAO 2005):

Powers (2004) brings an interesting perspective to risk management and the audit regulatory focus of organisations and his comments can equally apply to the NHS:

To avoid developing an NHS culture that could be termed ‘ossified’ and ‘risk-obsessed’, and to allow organisations and professions to exercise at least some degree of professional autonomy, we may need to try and educate the public to accept that failure is possible and that nurses and doctors cannot always guarantee a perfect treatment outcome. Patient expectations may have to be adjusted downwards.

“The safety culture within trusts is improving, driven largely by the Department’s clinical governance initiative and the development of more effective risk management systems in response to incentives under initiatives such as the NHS Litigation Authority’s Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts…. However, trusts are still predominantly reactive in their response to patient safety issues and parts of some organisations still operate a blame culture.

“The risk management of everything, and the specific growth of secondary risk management, has a dark side which is threatening the state, regulatory bodies, corporations and the individual experts on which so many individuals in society rely. If we must act as if we know the risks we face, then we must also create forms of risk management, and a related politics of uncertainty, which allows us to do this in more, rather than less, intelligent ways.

As Powers (2004) states:

The NHS may need to think less about regulation and audit and try to guard against its seemingly natural reactive tendency to create new organisations whenever a new major crisis happens. As Powers (2004) argues: ‘the test of good governance would not necessarily be the speed of their reaction to failure; on the contrary, it might be their ability, in Peter Senge’s phrase, “to take two aspirin and wait”.’

“the new politics of uncertainty must generate legitimacy for the possibility of failure. Indeed, in contrast to a ‘spin-’ or ‘reputation-culture’, such a political discourse would generate public trust precisely because an explicit discourse of possible failure is embedded in innovatory processes. The purpose would not be to defend individuals from blame, but to enrol the wider public in the benefits and excitement of innovation.

The political policy drivers who control and manage the NHS may not yet be ready for ‘Politics of Uncertainty’ (Powers 2004), but thought should be given to the concept, particularly in the consent to treatment process and in communication with patients generally. NHS policy makers also need to think more proactively and guard against their natural centralist regulatory tendencies.

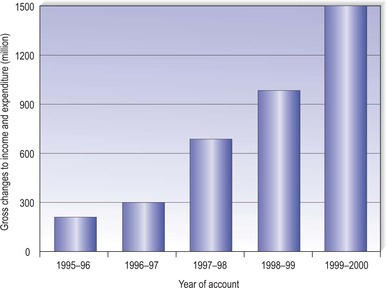

LITIGATION CLAIMS

Costs and claims in clinical negligence in the NHS have increased significantly. The National Audit Office states (2001) that ‘The rate of new claims per thousand finished consultant episodes rose by 72% between 1990 and 1998’. Figure 8 of their report (Fig. 3.1) places the issue in some perspective.

|

| Fig. 3.1Total charges to income and expenditure accounts for provisions for clinical negligence.Reproduced with permission from National Audit Office 2001 (author Karen Taylor). |

More recent figures are provided by the National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA) (National Health Service Litigation Authority 2006):

The costs and claims of clinical negligence are reported in billions of pounds sterling. Patient complaints to the Health Service Ombudsman (HSO) reach record levels each year: ‘This year we have handled a higher workload than ever. We received a record 4703 new complaints – an increase of 18% on the previous year, which had itself seen a huge rise in new complaints, many relating to continuing care’ (Health Service Ombudsman 2004).

“In 2004–05, 5609 claims of clinical negligence and 3766 claims of non-clinical negligence against NHS bodies were received by the NHSLA. This compares with 6251 claims of clinical negligence and 3819 claims of non-clinical negligence in 2003–04.

“… The NHSLA estimates that its total liabilities (the theoretical cost of paying all outstanding claims immediately, including those relating to incidents which have occurred but have not yet been reported to us) are £6.89 billion for clinical claims and £0.11 billion for non-clinical claims.

A patient may wish to complain and asks a nurse about appropriate channels. To function effectively as a patient advocate, the nurse must have a reason-able working knowledge and understanding of the complaints system and protocols (Tingle 1990), in particular his/her own local hospital complaints procedure. Minor complaints can often be handled by the nurse as they arise, and this is encouraged by Department of Health guidance. More significant complaints should be referred to the nurse’s line manager.

A rise in complaints or clinical negligence claims may not necessarily be directly attributable to a general deterioration in the quality of the health service, but rather to a much more informed, consumer orientated and less deferential public which maintains high expectations, (albeit perhaps unrealistic expectations) of the health service and what can be achieved. It is clear that a more vocal public is increasingly holding all types of professionals to account. Initiatives such as the Patient’s Charter (Department of Health 1995) and the Government’s health quality reforms (Department of Health, 1997 and Department of Health, 2000), which are intended to forge a quality-driven NHS, have raised patient expectations and helped draw attention to the patient’s right to complain. Government health policy has been in recent years to put the patient firmly at the centre of the NHS (The NHS Plan, Department of Health 2000) The NHS Plan worked from a pure patient focussed premise:

The Shipman case (Beecham 2000) and the Wisehart Bristol heart surgery scandal (Dyer 1999), widely reported by the media, have also kept medical and nursing matters well in the public eye, have inevitably driven up care expectations and, along with other medical scandals, have caused the government to reflect on complaint systems and other matters. Berrington & Barnwell (1995) discuss the Central Statistical Office publication Social Trends (vol. 25) and note: ‘Britons have become healthier, sometimes wealthier and more likely to own their own homes; higher expectations mean we are also increasingly dissatisfied’.

“10.1 Patients are the most important people in the health service. It doesn’t always appear that way. Too many patients feel talked at, rather than listened to. This has to change. NHS care has to be shaped around the convenience and concerns of patients.

Health complaints and litigation can be seen in a much broader and more generalised context: we live now in a much more complaining and litigation-conscious society. The mantle of infallibility exuded by many health carers seems to have been largely eroded in the minds of many patients today. We hold our health carers to account, like any other professionals involved in providing professional services. Health professionals may in some respects be at a disadvantage in that complaints made against them are more likely to attract media attention because of the ‘human interest’ factor. Finally, it must be remembered that, where a complaint is made in the context of health care, it is not simply a matter of ensuring that a fault is remedied. There is an important issue of public accountability in the context of the NHS (Simanowitz 1985).

Health-care provision is a matter of public funding and of public concern. There is an expectation that health-care providers should be accountable. Nurses need to be aware of the complaints process and the fact that they may be the subject of complaints made, whether at informal or formal level. It is also important that the nurse is aware of what rights patients have in this area regarding his/her role as patient advocate. Nurses also need to be aware of the mechanisms that have been developed to enhance patient safety as this is also an aspect of professional accountability.

Hill (1991) of the Medical Defence Union also offers some useful guidance on complaint handling: ‘When dealing with patients’ complaints remember the four S’s: complaints should be handled SPEEDILY, with SYMPATHY, to the patient’s SATISFACTION, and (if indicated) with an expression of SORROW. Conciliation, not confrontation should be the goal’.

It is important to remember that a complaint could result in litigation.

Complaints should be analysed for trends.

Complaints and patient confusion

Frequently a patient’s complaint, or the commencement of a legal claim, may arise from his/her confusion, anxiety and frustration at not receiving a satisfactory explanation of why something has gone wrong; frustration that may result in anger and trigger off a complaint (Medical Defence Union 1993). Litigation or a formal complaint might never have taken place had the patient been given an understandable explanation of what had gone wrong and the steps being taken to remedy matters. Vincent and colleagues (1994) surveyed 227 patients and relatives who were taking legal action through five firms of plaintiff solicitors. They found that the decision to take legal action was determined not only by the original injury but also by insensitive handling and poor communication after the original incident. The following four main factors were identified in the analysis of reasons for litigation:

Patients and relatives wished to see staff disciplined and called to account. They wanted an explanation and felt ignored or neglected after the incident. They also wanted to make sure that the same problem did not happen to anybody else.

• Accountability

• Explanation

• Standards of care

• Compensation and admission of negligence

Complaints can arise from what may seem to the health carer to be trivial matters. The diabetic clinic may have been very busy and short-staffed at a particular time. As a result the patient may have had a long wait for treatment. An overworked nurse may have been a little abrupt when the patient asked how much longer he was going to have to wait. The patient takes offence at what he sees as a personal insult and complains. But some matters are more complex and may raise issues of such gravity that monetary compensation is required as well as an explanation.

Complaints may or may not have a reasonable basis. Truelove (1985) states:

“Some people complain only reluctantly and as a last resort, when prompted by a deep emotion. Some complain reasonably on reasonable grounds. Some complain ‘unreasonably’ on reasonable grounds. Some complain ‘reasonably’ on unreasonable grounds. A few (usually with a history of psychological disturbance) complain unreasonably on unreasonable grounds. A few seem to be ‘born complainants’ who relish a battle and will complain on any grounds whatsoever.

THE COMPLAINTS SYSTEM

Unfortunately there are a number of weaknesses with the present NHS complaints system, the HSO states (Health Service Ombudsman 2005):

This is quite a condemning catalogue of complaints on the NHS complaints system, and although reform is taking place, it is rather slow and piecemeal. The complaints system as presently constituted is confusing and there is a lot of scope for improvement. We are still some way off from having a full and comprehensive system.

“complaints systems are fragmented within the NHS, between the NHS and private health care systems, and between health and social care; the complaints system is not centred on the patient’s needs; there is a lack of capacity and competence among staff to deliver a quality service; the right leadership, culture and governance are not in place; just remedies are not being secured for justified complaints.

The HSO is not alone in noting problems. The Healthcare Commission (2005) has seen a doubling in the numbers of people demanding that an NHS complaint should be independently reviewed because it was not resolved locally. They are sending one in three cases back to the NHS because the NHS has not dealt with the issues adequately.

The Department of Health response, in January 2002, to the report of the public inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary (Department of Health 2002) said that they intended to have a new NHS complaints procedure in place by December 2002, but this new system has yet to be fully implemented and integrated across the NHS. At the time of writing (April 2006), the arrangements for ‘local resolution’ set out in the Complaints Regulations 2004 do not apply to primary care practitioners (GPs). The practice-based procedure booklets issued to primary care practitioners in 1996 continue to apply until the amended complaint regulations and guidance are issued in 2006. Following an approach by the Shipman Inquiry, ministers decided on a ‘phased implementation’ of the complaints system. The intention is to issue amended Complaints Regulations in 2006 once the Department of Health has been able to give proper consideration to any recommendations made by the Shipman Inquiry, which published its fifth report on 9 December 2004. The guidance will also be revised at that time. NHS Foundation Trusts have their own complaints procedures for dealing with internal complaints and these may differ from the ‘local resolution’ process that applies to other Trusts (Department of Health 2006a).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree