Chapter 4 Patient safety

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Patient positioning

Patient transfer

These factors will influence the team’s preparation and the equipment required to carry out the transfer. The patient’s age and mobility have a bearing on the resources required; for example, a well, mobile patient may be able to move to the operating table unaided. In contrast, an elderly, frail or less mobile patient will require greater assistance from the surgical team and equipment. Particular care, planning and/or equipment is required to manage frail, elderly patients (those over 80 years of age) or obese patients, especially the morbidly obese (Phillips, 2007). The latter require specialised lifting equipment (e.g. ‘hover mats’) and purpose-designed operating tables and fittings to accommodate them safely intraoperatively, and to protect staff.

Care must be taken when transferring patients with intravenous (IV) cannula(s), IV infusions, drains, catheters or other items already in place. Their dislodgement can create discomfort (or worse) and replacing them is time-consuming. The planned procedure, patient condition, and staff and equipment availability will determine whether the initial transfer occurs while the patient is conscious or following induction of anaesthesia. Additionally, consideration must be given for patients who need repositioning intraoperatively (e.g. during bilateral hip replacement), as disorganised or unplanned movements during repositioning increase the risk of damage to the initial operative site, or can result in airway compromise.

Surgeon, anaesthetist and other staff requirements for patient access need to be considered. At all times, the anaesthetist must be able to ensure ventilatory adequacy, have IV access and address requirements for haemodynamic monitoring. The surgeon needs access to the surgical site and the instrument nurse needs to be able to maintain a sterile field throughout the procedure (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007). Consequently, the patient’s position is often a compromise between competing demands for surgical access balanced against the patient’s need for safety and protection (Hamlin, 2005a).

Transfer methods and rationales

All surgical team members have equal responsibility for maintaining patient safety during transfer. The anaesthetist, who has responsibility for the patient’s airway, generally coordinates the lift (Heizenroth, 2007). The duty of the registered nurse (RN) is to assess the surgical environment and patient, and ensure that the most appropriate transfer equipment, positional aids and staff are available. During the transfer a team leader, usually (but not always) the anaesthetist, directs the team, including the patient if he or she is conscious. When the patient is anaesthetised and/or unconscious, this role will normally revert to the anaesthetist, as maintenance of a patent airway and ventilation are the main priorities (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007).

Complications

Injuries associated with patient transfer include skin tears, joint dislocations, muscle and/or nerve damage, obstruction or dislodgement of IV infusion tubing or catheters, and patient falls (Phillips, 2007). Additionally, staff members risk injury. These incidents occur when:

Patient positioning

Patients are immobile during surgery and, because they are no longer able to change and control their body position, they are at an increased risk of developing decubitus ulcers, venous thromboembolism and pulmonary dysfunction (Fulbrook & Grealy, 2007). Additionally, unconscious, immobile patients cannot change an uncomfortable position or complain of discomfort or pain related to their position.

Anatomical and physiological considerations for patient positioning

A patient’s tolerance of the stresses imposed by the surgical intervention depends significantly on the normal functioning of the vital systems, and each body system must be considered when planning the patient’s position for surgery. The goals of positioning include the prevention of injury from pressure, crushing, stretching, pinching or obstruction (Phillips, 2007). The development of such injuries is influenced by the:

Integumentary system

The integumentary system can be injured as a result of the physical forces used to maintain the surgical position, as well as the way the patient is moved. These physical forces include pressure, shear and friction (Heizenroth, 2007).

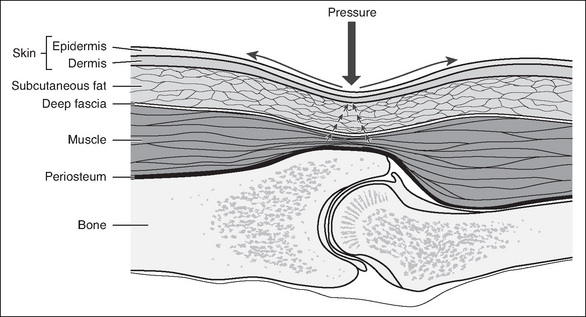

Pressure

Pressure is the force placed on the patient’s underlying tissues. In order to avoid injury, normal capillary interface pressure (23–32 mmHg) must be maintained (Phillips, 2007). Above these levels, blood flow and tissue perfusion become restricted (see Fig 4-1). Pressure can be created by the patient’s own body weight as gravity presses it downwards. It can also be the weight of devices that are placed on or against the patient, such as instruments, drills or Mayo stands, or surgical team members leaning on the patient. Additionally, bed attachments or positioning aids can press against or pinch parts of the patient’s body.

Shear

Shear is the movement of underlying tissue when the skeletal structure moves while the skin remains stationary. A parallel force creates shear. This occurs when, for example, the head of the operating table is lowered and the patient is placed in a head-down, supine position (Trendelenburg). As gravity pulls the skeleton down, the underlying tissues are stretched, folded or torn as they move with it. This can result in vascular occlusion as well as damaging the (static) skin (Heizenroth, 2007; Phillips, 2007).

Friction

Friction is the force produced when two surfaces rub against each other. Friction to the patient’s skin occurs when the body is dragged across the operating table rather than lifted; this can abrade, burn or tear the patient’s skin and encourage the development of decubitus ulcers (Hamlin, 2008).

The use of a pressure sore risk assessment tool preoperatively can assist in determining the degree of individual patient risk; however, there is limited evidence of the use of such tools (or other preoperative assessment activities) by perioperative nurses, although their use by ward staff may be indicated on the patient’s preoperative checklist (Hurley & McAleavy, 2006).

Musculoskeletal system

During surgery and anaesthesia, normal protective reflexes (e.g. pain and pressure receptors) are depressed in the patient and muscle tone is lost as a result of the action of the pharmacological agents used. Consequently, patients are no longer able to respond normally if, during positioning and surgery, their muscles, tendons and/or ligaments are overstretched, twisted or strained, or body alignment is not maintained. Injury can also occur if dependent limbs fall over the edge of the operating table. It is advisable to use a body strap/safety belt to secure the patient to the operating table.

Nervous system

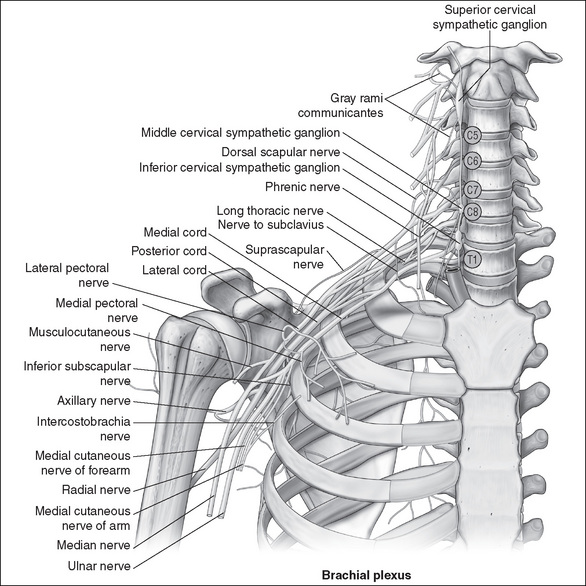

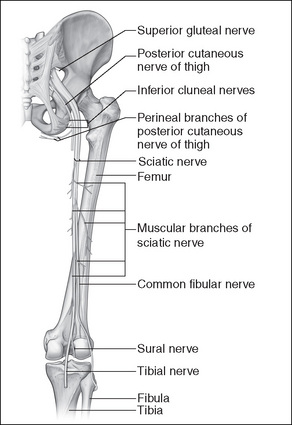

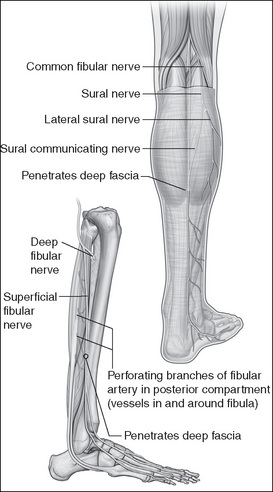

The action of anaesthetic agents, which cause a loss of sensation and protective reflexes, increases the likelihood of nerve injury occurring. In most cases these injuries occur due to the formation of lesions, secondary to damage incurred by undue pressure, stretching, twisting and pinching of nerves. The ulnar nerve is the nerve most frequently injured during the perioperative period (Rank, 2008). Table 4-1 outlines nerves that are commonly injured and the causes (Heizenroth, 2007).

Table 4-1 Peripheral nerves at risk of injury

| Nerve involved | Cause of damage |

|---|---|

| Brachial plexus | |

| Median, radial and ulnar nerves | • Pressure on the medial aspect of the patient’s arm when devices used to secure the arm are unpadded, or restraints are too tight |

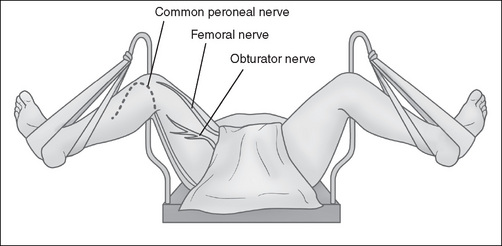

| Femoral nerve | |

| Sciatic nerve | |

| Common peroneal nerve | • Pressure of the stirrups or leg-holding devices on the patient’s calf when in lithotomy position (all variants) |

Cardiovascular system

Anaesthetic agents can affect the cardiovascular system by causing peripheral vasodilation and subsequent pooling of blood in the extremities, resulting in hypotension (Heizenroth, 2007). Patient positioning can further affect this phenomenon; for example, a head-up, supine (reverse Trendelenburg) position will cause blood to pool in the lower extremities. Consequently, the movement of patients into and out of these positions must be measured and unhurried. Pregnant patients and those with large abdominal masses are particularly at risk of supine hypotensive syndrome (Fell & Kirkbride, 2007).

Adequate arterial circulation is necessary to perfuse tissue, and occlusion or pressure on peripheral vessels, such as might be caused by positioning devices or safety belts/ straps, must be avoided (Phillips, 2007). For example, patients who are placed in the lithotomy position are at risk of compartment syndrome in their lower limb(s), which occurs when perfusion pressure falls below tissue pressure in a closed anatomical space or compartment (Wilde, 2004). This can occur when patients are in this position for extended periods of time. Compartment syndrome develops via a combination of prolonged tissue ischaemia and subsequent reperfusion of muscle within a tight osseofascial compartment and, untreated, leads to necrosis and functional impairment (Dua et al., 2002).

Respiratory system

Respiratory function can also be compromised, particularly when a patient is positioned head-down, supine (Trendelenburg), which causes the abdominal viscera and organs to shift up towards the diaphragm, subsequently affecting inspiratory and expiratory tidal volumes. This is especially so for patients who are obese, pregnant or have pre-existing respiratory disease (Heizenroth, 2007). The prone position also impedes respiratory function. Ideally, patients should spend as little time as possible in these positions. Excessive pressure caused by positional aids or the placement of the patients’ arms on the chest area should also be avoided (Heizenroth, 2007).

Surgical positions

Supine position

In the supine position, patients lie on their back with their arms either secured at their sides or placed out on an arm board. This commonly used position provides access to the abdominal, peritoneal and cardiothoracic cavities, the extremities and the head and neck. Table 4-2 shows nursing interventions and rationales for this position.

Table 4-2 Supine position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress—gel mattress or air support surface overlay. | 1. Padding or special mattress overlays protect occiput, scapulae, olecranon, vertebrae, sacrum, coccyx and calcaneus from undue pressure. |

| 2. Padding or gel pads placed on extensions or other positional aids as required (arm boards, J boards). | 2. Protects ulnar nerve from pressure-induced damage. |

| 3. Heels may require padding/sheepskin bootees, especially if the patient is elderly or malnourished. | 3. Padding/bootees protect the heels from undue pressure. |

| 4. Keep arm board(s) level with the operating table and at an angle of 90° (or less). Arm(s) must be loosely secured to the board. | 4. Protects peripheral vasculature and nerves from damage, including the brachial plexus and ulnar nerve. |

| 5. Legs remain uncrossed at the ankle. | 5. Relieves undue pressure, decreasing risk of venous thrombosis. |

Prone position

In the prone position, patients lie face down. This position is used when surgical access to the spine, rectum or dorsal areas of the extremities is required. It can be achieved on a standard operating table or it may require a specially designed table or table fittings (e.g. a laminectomy frame); the choice is determined by the particular surgical intervention.

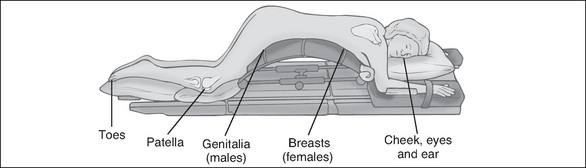

The patient is anaesthetised in the supine position prior to transfer, and the airway is secured using a reinforced, flexible endotracheal tube (ETT), which will not kink. The ETT is secured with tape by the anaesthetist. The patient is then lifted and placed with the abdomen down on the operating table, and the face turned to one side. This transfer requires a minimum of four people to be executed safely, with one member of the team, usually the anaesthetist, supporting the patient’s head and neck and safeguarding the airway at all times. The position requires additional padding (often in the form of multiple pillows or rolls on the operating table) to protect vulnerable areas, such as patient’s ear and cheek on the dependent side, the breasts (females), genitalia (males), patellae and toes (see Fig 4-6). Table 4-3 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the prone position.

Table 4-3 Prone position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress—gel mattress or pillows/rolls (or gel pad over laminectomy frame, if used). | 1. Extra padding needed to protect vulnerable areas, such as the dependent cheek, ear, breasts (female), genitalia (males), patellae and toes. |

| 2. Padding placed on extensions as required (arm boards, J boards). Arms should be secured loosely, palm down on padded arm boards and kept in natural alignment. They should not be allowed to hang over the edge of the operating table. | 2. Arms are moved down and forward and placed on the arm board slowly and carefully to minimise the risk of damage to the brachial plexus. Arms hanging over the table edge can sustain damage to the radial nerve. |

| 3. Eye ointment placed in both eyes, eyelids are then securely taped closed. | 3. The eyes are vulnerable to corneal abrasion. |

Lateral position

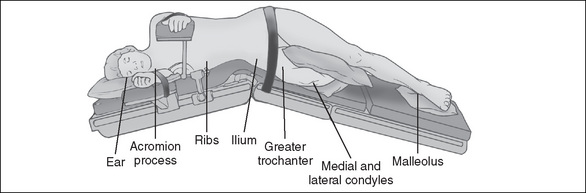

In the lateral position, which is used for procedures involving the chest, kidney or hip joint, the patient lies on the non-operative (dependent) side, with the operative side uppermost. It requires a selection of positional aids to secure the patient because there is a risk of the patient rolling forward or backwards intraoperatively or even falling off the table. The patient is anaesthetised in the supine position and then transferred or turned onto the dependent (non-operative) side. Positional aids include specially designed, padded arm rests (e.g. Carter Brain arm rest) to support the upper arm and keep it away from the operative area; table/safety straps and pliable bean bags are used to hold the patient securely to the operating table and maintain the position throughout surgery (Fig 4-7). Alternatively, padded table attachments (lateral supports or kidney braces), one at the patient’s back and a larger one supporting the abdomen, can be used. Table 4-4 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the lateral position.

Table 4-4 Lateral position—nursing interventions and rationales

| Nursing intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Padded operating table mattress and padding placed on extensions as required (arm boards and arm supports) and pillow for head. | 1. Protection of pressure points on the dependent side—the ear, shoulder, hip, ankle. |

| 2. Pillow is placed between the patient’s knees. | 2. Knees will rub against each other, damaging the skin; additionally, undue pressure can damage the peroneal nerve. |

| 3. Spine is kept in alignment by placing a pillow under the patient’s head. | 3. The spine is vulnerable to misalignment and twisting; this misalignment can place pressure on the dependent brachial plexus. |

| 4. Patient needs securing by the use of either lateral supports (kidney braces) (padded) at the abdomen and back, or the use of devices such as bean bags or a Vac-Pac and a safety belt/ table strap over the patient’s upper thigh. | 4. Prevents the patient from falling off the operating table. The use of these devices also ensures the patient does not move intraoperatively. |

| 5. Ensure the patient’s shoulder on the non-operative (dependent) side is not over-extended and the lower arm is protected, usually by securing it to an arm board. The upper arm is placed on a lateral arm support. | 5. Prevents damage to the brachial plexus and ulnar nerve. |

| 6. Kidney surgery requires access to the retroperitoneal area of the flank. In this case, the patient is positioned so that the lower iliac crestis below the lumbar break where the kidney bridge is located on operating table. The latter is subsequently elevated (slowly) and the operating table flexed to lower the patient’s upper torsoand legs. | 6. Prevents the dependent flank area from compression and subsequent pooling of blood in the lower extremities. |

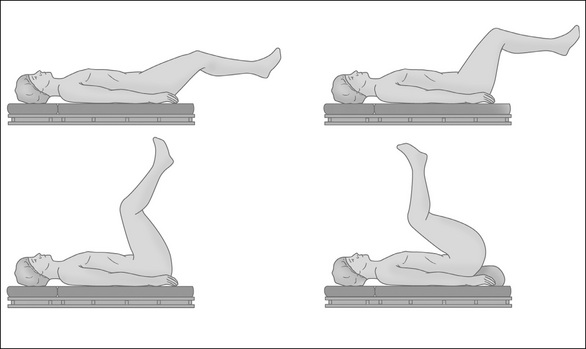

Lithotomy position

For patients undergoing gynaecological and urological surgery, the lithotomy position is required. This position involves the patient lying supine with their legs raised, abducted and secured in leg positioning devices (stirrups) to expose the perineal area. Depending on the surgical access required, the patient’s legs can be held at various angles to the trunk—in a low, standard or high lithotomy position. These positions are maintained with the use of a range of stirrups, which are chosen after considering the type of surgery and proposed length of time for the procedure (Figs 4-8, 4-9). One of the most important precautions to consider while placing a patient in this position is the high risk of nerve damage and hip dislocation if the legs are not raised simultaneously, slowly and at the same angle and height at all times. Table 4-5 shows nursing interventions and rationales for the lithotomy position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree