. PATIENT CARE

Adhere to Established Patient Screening Procedures: Interview the Patient85

Obtain Patient History85

Obtain Vital Signs and Measurements85

Obtain the Chief Complaint89

Documentation91

Other Guidelines for Documentation94

Medication Administration95

Medication Calculations97

Routes and Sites for Administering Parenteral Medication103

Controlled Substances110

Preparing Patients for Examinations and Treatments113

Assisting with Office Surgery: Commonly Used Instruments and Supplies119

Emergency Care129

PREPARE AND MAINTAIN THE EXAMINATION AND TREATMENT AREAS AND INSTRUMENTS

Before the first use of an examination room each day and between examinations, the room must be prepared for each new patient. Equipment and surfaces such as countertops and chairs need to be sanitized, disinfected, or sterilized.

PREPARING THE EXAMINATION ROOM

• Stock and place in position all necessary equipment and supplies.

• Clean the room, discarding used supplies in wastebasket or appropriate biohazard container.

• Sanitize and disinfect surfaces and instruments if necessary.

PREPARING FOR THE PATIENT EXAMINATION

• Clean stethoscope ear pieces and bell with alcohol wipes.

• Store used instruments out of sight in a soaking solution until they can be cleaned.

• Disinfect contaminated surfaces with a 1:10 bleach solution (wear heavy-duty rubber gloves).

• Make fresh bleach solution each day or each 8-hour shift.

SANITIZING INSTRUMENTS

• Wear heavy-duty rubber gloves, apron or laboratory coat, and eye protection.

• Collect all soiled instruments and rinse in cold water, then place gently in a basin of warm, sudsy water.

• One instrument at a time, use a scrub brush to cleanse all surfaces, rinse thoroughly under hot water, and place on paper towels to dry. (Leave instruments with ratchets, jaws, and blades open.)

• With more paper towels, gently dry instruments.

• Clean and rinse basin thoroughly; clean rubber gloves and store the gloves with basin.

• Wash hands.

When interviewing a patient, you need to ensure you are obtaining all of the necessary information and presenting that information in a format that is useful to the physician.

Although the patient has been asked questions about his or her billing and insurance at the front desk and has often filled out a written health history questionnaire while waiting to be seen, you should take the patient to a private area to discuss his or her medical history and the current health problem that has brought the patient to the office that day.

OBTAIN PATIENT HISTORY

Complete the office’s medical history form by either asking the patient each question on the form or by having the patient fill out the form on his or her own. Go over it to ensure all information is complete.

OBTAIN VITAL SIGNS AND MEASUREMENTS

The medical assistant (MA) usually takes vital signs and measurements at every office visit. Follow the office procedure for taking and documenting vital signs.

HEIGHT AND WEIGHT

The MA usually measures height or length and weight of infants and children at every well-baby or well-child visit. The head and chest circumferences of infants are also measured and recorded. For adults, the height is measured at the initial visit, and weight is usually measured at every visit. Changes in weight other than normal growth during childhood should be noted. Large drops in weight for a patient of any age should be explored.

TEMPERATURE

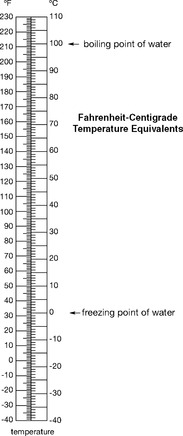

In some offices, the MA takes a patient’s temperature at every visit, but in others he or she takes a patient’s temperature only when an infection is possible or signs and symptoms of a fever are present. When taking a temperature, use the method appropriate for the patient’s age and health status. The figure on the following page shows Fahrenheit/Centigrade temperature conversions.

PULSE

Pulse should be recorded for adults and children. If the patient’s pulse is regular, measure for 30 seconds and double; if the pulse is irregular, measure for a full 60 seconds.

Document the pulse rate and include the volume only if the pulse is extremely strong (bounding) or weak (thready). Document whether the pulse is irregular. The pulse is usually taken apically for an infant.

RESPIRATIONS

Respirations should be recorded for adults and children. If the patient’s respirations are regular, measure for 30 seconds and double; if the respirations are irregular, measure for a full 60 seconds.

Count while the patient is unaware—keep your fingers on the wrist using the same amount of pressure so that the patient thinks you are still measuring pulse. This discourages the patient from talking or altering his or her respiratory rate.

|

Blood pressure is the pressure of the blood against the walls of arteries. The systolic pressure refers to the pressure when the heart’s ventricle contracts. The diastolic pressure refers to the pressure when the ventricles relax between heartbeats.

When measuring blood pressure:

• Select the proper cuff size; the width of the cuff should be one-third larger than the diameter of the arm.

• Apply the cuff snugly with the center of the bladder over the brachial artery.

• To determine how high to pump for a current patient, check the chart for the blood pressure on the last visit.

• To determine how high to pump for a new patient, palpate the systolic pressure. To do this, place your first finger on the radial pulse and pump up cuff. Note where the pulse disappears (approximate systolic pressure). Add 30 mm Hg to that point when auscultating the blood pressure.

• Pump up to 30 mm Hg above the expected blood pressure.

• Release valve so blood pressure indicator decreases 2 to 4 mm Hg per second.

• Note when the first sound is heard (systolic pressure).

• Note when the last sound is heard (diastolic pressure).

• Deflate the cuff fully.

• Record the blood pressure as a fraction (e.g., 122/82) using only even numbers. Note on which arm the blood pressure was taken. Note whether the patient was lying down or standing.

• If the patient has been keeping a log of his or her blood pressure readings since the last visit, place this in the patient record for the physician.

OBTAIN THE CHIEF COMPLAINT

The chief complaint is the reason the patient has come to the office today.

Ask, “What brings you to the office today?” or “What is the reason for your visit today?”

Ask the patient to describe the symptoms—changes in physical condition that the patient experiences through his or her senses or as a sensation (e.g., pain, nausea, itching); or as a feeling (e.g., anger, sadness). Symptoms are subjective complaints, which means they are experienced in different ways by different people. In addition, note any signs—changes that can be observed or measured—such as redness, swelling, or pallor.

A discussion of the chief complaint is sometimes known as the history of the present illness (HPI). You should try to obtain the following seven pieces of information that can be used to describe the patient’s chief complaint:

(1) location of symptoms; (2) quality of symptoms; (3) severity of symptoms; (4) chron-ology of the illness; (5) how the illness began; (6) what makes the illness better or worse; and (7) associated symptoms.

Location is the exact place in the body the symptom is felt. Ask, “Where exactly does it hurt?” or “Can you show me exactly where it hurts?” to get the patient to pinpoint the location.

QUALITY

The quality of a symptom refers to how one describes or characterizes the symptom. The quality of pain can be described as sharp, throbbing, dull, burning, or crampy.

SEVERITY

The severity helps describe quantitative aspects of an illness. Are symptoms intense, moderate, or mild? You might ask the patient to rate the symptoms on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being undetectable and 10 being extremely uncomfortable.

CHRONOLOGY

Chronology asks the patient to explain how the illness began and how the symptoms have changed between then and now.

HOW IT BEGAN

How it began is self-explanatory, but it may be important to determining what the patient was doing when the symptoms began is important to see whether a particular activity or a particular place could have had an effect on the onset of the illness or episode (e.g., chest pain with vigorous activity, asthma attack at the zoo).

WHAT MAKES IT BETTER OR WORSE

Ask what the patient has done to try to alleviate the symptoms and whether any effects have occurred.

Associated symptoms gets at the minor symptoms that occur around any disease process. For instance, a sore throat or ear pain is often accompanied by a fever or stuffy nose; a stuffy nose with no fever suggests that the sore throat is being caused by a virus, whereas fever with a sore throat but no stuffy nose suggests a bacterial infection.

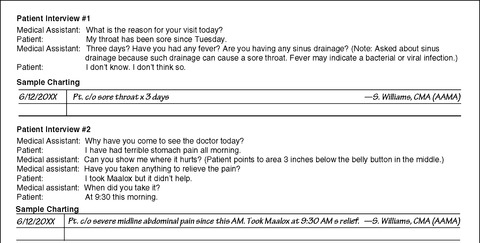

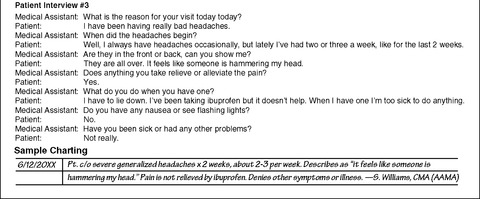

DOCUMENTATION

Documentation of the patient history, vital signs, and statement of the chief complaint is extremely important. The chief complaint should be documented with the length of time the patient has had the symptoms, accurately and precisely.

Use medical terminology and appropriate abbreviations.

Remember, everything in a patient’s medical record is a legal document. If you directly document the medical record, follow the guidelines provided later in this section. If you record vital signs and the chief complaint electronically, make sure to type correctly into the electronic medical record.

If you use the patient’s own words, put the patient’s words in quotes. For instance, the patient states, “My chest feels like a truck is on it.”

Make sure to state only your observations and the objective data you have obtained from various tests. (See the figure on pp. 92–93 for a sample documentation of the chief complaint.)

Many physicians use the SOAP format for documentation, and you may be asked to write your findings using this format. The SOAP charting format has the following four main components: (1) Subjective impressions, (2) Objective data, (3) Assessment, and (4) Plan.

|

|

Subjective impressions are those that the patient has about his or her own condition, the things the patient describes that only the patient can experience—the symptoms.

Note: Make sure to gather the data from the patient if the patient is coherent, not from another person (e.g., family member, friend) speaking on the patient’s behalf.

OBJECTIVE DATA

Objective data are information that can be observed or measured—the signs. Objective data include measurements, vital signs, and results of ordered tests.

ASSESSMENT

Assessment is a summary of what the subjective and objective information, taken together, means. In a physician’s charting, assessment is often written as a first impression of a possible diagnosis. An MA should always avoid using any term that is a medical diagnosis.

PLAN

The plan is a written description of the diagnostic tests the patient will undergo, medications that will be prescribed, treatments that will be given, and follow-up the patient will receive.

OTHER GUIDELINES FOR DOCUMENTATION

1. If you chart directly in the patient record, double-check to make sure it is the correct record.

3. All entries to a patient record are added in chronologic order.

4. Draw a line through any unused lines to avoid charting out of chronologic order.

5. If you make a mistake, do not erase. Draw a single line through the mistake and initial it. If you make a correction on a different date than the original entry, date and initial the correction.

MEDICATION ADMINISTRATION

In many states, MAs are able to administer oral and parenteral medications in the medical office. Because medication administration can pose a risk to any patient, the MA must always be careful to follow the correct procedure and take all possible measures to prevent injury or adverse effects.

Because MAs are not specifically licensed to administer medications in most states, they should never give patients medication unless the physician or provider is present in the office to respond to any problem or adverse effect. MAs are not allowed to administer intravenous medications.

FIVE RIGHTS OF MEDICATION ADMINISTRATION

Any time you are asked to administer a medication, make sure you are adhering to the five “RIGHTS” of medication administration. In addition, you must always accurately document in the patient’s medical record any medication that you administer.

Right drug—Prepare the medication from the written order in the patient’s medical record. In hospitals or practices with electronic medical record systems, drugs are prepared from transcribed medication orders. Check the label of the bottle or package containing the drug against the medication order to ensure they are the same. The label should be checked three times: (1) when the bottle is removed from the medication drawer or cabinet, (2) when the medication is removed from the bottle, and (3) when the medication is returned to storage.

Right dose—The drug is prescribed to achieve a specific effect. Giving too little medication may be ineffective; giving too much may cause harm to the patient. If a calculation is necessary, accurately calculate the dose before preparing the medication and work from your written calculation. If you have questions, ask another staff member to verify your calculations. Accurately measure liquid medications.

Right patient—Always verify that a medication is being administered to the right patient. To accomplish this in an ambulatory care setting, take the patient’s medical record with the medication to the patient. Ask the patient to state his or her name and verify it from the page of the medical record that contains the written medication order.

Right time—In the physician’s office, the time of day is usually less important than the interval between doses, as, for example, a series of hepatitis B immunizations or diptheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) immunizations. Verify that the correct amount of time has passed since the last dose of the medication, and refer any questions to the physician.

Right route—The medication must be given by the correct route to have the desired effect and, in the case of some injections, to prevent tissue injury. When giving injections, choose a needle length that will deposit the medication into the desired tissue based on the size of the patient and angle of administration. If you have questions, clarify the order with the physician or nurse practitioner who originated the order.

MEDICATION CALCULATIONS

Before preparing a medication, calculating the correct dose is often necessary. Any medication calculation can be expressed as a proportion, where the unknown (x) is the amount to give. Refer to the table in Tab 12, pp. 214–216, if you need to review abbreviations used in calculating and preparing medications.

CALCULATING A DOSE OF SOLID MEDICATION

In the case of a solid medication, you know the strength available per tablet or capsule and must calculate the number of tablets or capsules to administer.

The equation is the following:

The equation to calculate the correct dose to administer is the following:

To solve a fraction, remember to divide the bottom number into the top number.

CALCULATING A DOSE OF LIQUID MEDICATION

When a liquid medication is expressed in a unit of one (e.g., per teaspoon), the equation can be solved the same way as for a solid medication.

When a liquid medication is expressed in units other than one, the calculation is more complex. Two methods can be used to solve such an equation: (1) two step, and (2) one step.

For example, the physician orders erythromycin, oral suspension, 250 mg. The label on the bottle says there are 125 mg per 5 ml.

TWO-STEP CALCULATION

Step 1. Calculate the number of milligrams in 1 ml by dividing 5 into 125.

Step 2. Using the number of milligrams per milliliter, calculate the desired dose, setting up the fraction with the dose ordered over the dose per milliliter:

The desired dose or amount to administer to the patient, is 10 ml.

Use the following formula to find the dose using only one calculation. Remember, the parentheses in a formula mean that you should multiply.

For the problem at hand, the equation is:

As in the two-step method, you should administer 10 ml of the medication. If you need to review prefixes in the metric system, review the following table:

| No | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Prefixes | Prefix | Greek Prefixes | ||||

| micro- | milli- | deci- | none | deca- | hecto- | kilo- |

| 0.000001 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | 100 | 1000 |

| millionth | thousandth | tenth | one | ten | hundred | thousand |

PEDIATRIC DOSES

You can calculate a pediatric dose using either body weight or body surface area (BSA). To calculate a pediatric dose by body weight (expressed in kilograms), use the following three-step procedure:

Step 1. Calculate the number of kilograms in the child’s weight. The conversion formula is 2.2 lb = 1 kg. To change pounds to kilograms, divide the number of pounds by 2.2.

Step 2. Calculate the number of milligrams to administer each day.

Example: A physician orders medication for a child at 10 mg/kg per day to be administered in two divided doses. The child weighs 75 pounds.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access