Chapter 3. Participative Approaches to Research

Ruth Northway

▪ Introduction

▪ The context of participatory research

▪ The nature of participatory research

▪ The relevance of participatory research to nursing

▪ Example – the ‘ForUs’ study

▪ Conclusion

Introduction

Tetley and Hanson (2000) suggest that a definition of participatory research ‘remains elusive’. However, for the purpose of this chapter, it will be defined as a continuum of research approaches which recognise that, traditionally, some groups of people have tended to be marginalised and powerless within the research process and that this can be oppressive. In order to change such a situation participatory research thus seeks to promote and facilitate the active involvement of such groups (often referred to as ‘the community’) at all stages of the research process. It is concerned with both changing power relations within the research process and with producing knowledge which can be used to bring about wider change and transformation. Action and education are integral parts of participatory research.

The context of participatory research

The origins of participatory research are said to lie in Tanzania in the 1970s (Hall 1992) and the first meeting of the International Participatory Research Network produced a definition of such research (Hall & Kidd 1978) emphasising its focus on promoting the active participation of powerless groups at all stages of the research process. The term participatory action research is also sometimes used but whilst Park (1999) acknowledges that this may be a more accurate reflection of the action component of participatory research, it can lead to some confusion with action research in which a professional researcher directs the research. Khanlou and Peter (2005) argue that action research and participatory research differ in terms of ideological beliefs, the training of researchers, and the context in which they work. The former is grounded in clinical and social psychology and management theory whereas the latter is usually undertaken by community organisers and adult educators, being informed by sociology, economics and political science (Khanlou & Peter 2005).

A further term encountered is ‘emancipatory research’. Such terminology is often found in the disability literature where some authors (such as Stalker 1998) argue that participatory and emancipatory research are used interchangeably. Others (e.g. Chappell 2000) draw a clear distinction, arguing that whilst participatory research aims to increase the participation of disabled people, emancipatory research transforms the material and social relations of research such that disabled people control all aspects of the research process. Yet other authors (e.g. Beresford 2005, Finn 1994 and Northway 2003) argue that participatory research is best viewed as a continuum in which there are increasing levels of participation on the part of those who have traditionally held less powerful positions and in which they are enabled to take control over the research process. INVOLVE (2004) suggest that on such a continuum a distinction can be made between user consultation, collaboration and control. In this chapter, the term ‘participatory research’ will be used as an umbrella term for a range of research approaches which seek to shift control from powerful to less powerful groups within the research process by consultation, collaboration and facilitating control.

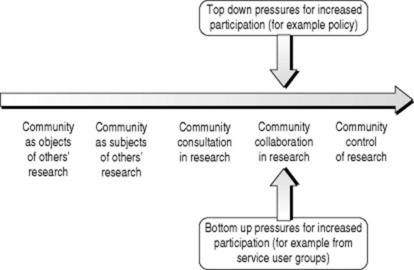

Whilst traditional approaches to analysing participation have tended to concentrate on the level of involvement (as above), the focus has now shifted to include examination of the ‘ideological underpinnings’ of the differing approaches to participation (Beresford 2005). The driving forces for increased participation of marginalised groups in research can broadly be labelled ‘top down’ (policy driven) and ‘bottom up’ (service user driven).

INVOLVE (2004) note that, since 1997, a range of health policy documents in the United Kingdom have emphasised the importance of public participation. In addition, some research funders stress the importance of service user involvement. Ross et al (2005) thus note that the drive for consumer involvement in their project came from both policy and the research commissioning process. Service user pressure for increased participation in, and control over, research can be seen from the disability movement in the United Kingdom, who have criticised the negative and oppressive nature of much disability research (see, for example, Oliver 1992) and who have called for control of the research process to lie with disabled people themselves.

It is evident, however, that these two dimensions of participatory research both need to be considered (Fig. 3.1) since the primary motivation for undertaking a project may be to respond to policy but the outcome of the research may be to devolve maximum control to service users. Alternatively the impetus for research may arise from a service user group but they may not wish for full participation or control at every stage of the project. Furthermore, the level and nature of participation may vary from stage to stage.

|

| Figure 3.1 The dimensions of participatory research approaches. |

The nature of participatory research

Some authors (such as Soltis-Jarrett 2004) suggest that participatory research is a qualitative approach whilst others (such as Macaulay et al 1999) argue that it can be both quantitative and qualitative. Seng (1998) thus states that participatory research cannot be recognised as ‘one particular method or design’. Instead it is more helpful to view it in terms of how the research should be conducted rather than in terms of data collection techniques (Henderson 1995) since it addresses how the research process should proceed (Huang & Wang 2005). Four key features (Box 3.1) will be discussed.

Box 3.1

The key features of participatory research

▪ A focus on countering oppression

▪ Promoting participation at all stages of the research process

▪ The production of ‘useful’ knowledge to promote change

▪ A different role for the researcher

Countering oppression

Some groups have been marginalised within the research process and are often relatively powerless due to the fact that their views are not heard (Stoeker & Bonacich 1992). This position is oppressive and participatory research seeks to counter such oppression by promoting active participation at all stages of the research process.

A key feature of participatory research is the involvement of a ‘community’ (Park 1999), but such communities are often disempowered in diverse ways. Whilst participatory approaches in the context of health research have often been viewed as synonymous with service user involvement in research, Beresford (2005) argues that both service users and practitioners should be considered in this.

Participation at all stages of the research process

A key feature of participatory research is that the community actively engage as fully as possible at all stages of the research process (Park 1999). Since the emphasis is on shifting power and increasing community control Stoeker (1999, p. 850) has identified six key points at which decisions need to be made:

▪ ‘defining the research question;

▪ designing the research;

▪ implementing the research design;

▪ analysing the research data;

▪ reporting the research results;

▪ acting on the research results.’

Participatory research can be cyclical, with action leading to the identification of further research questions. However, whilst participation at all stages is an ‘ideal’ model, the community may not wish for such involvement and, even where participation has been agreed, it may not be continuous or predictable (Cornwall & Jewkes 1995). Roles, responsibilities and contributions may thus shift as a project progresses (Macaulay et al 1999).

Within participatory research the research question or issue to be explored should be identified by the community themselves. However, Park (1999)acknowledges that the deprivation often experienced by such communities can militate against their initiating research.

Community members may have limited knowledge of the research process and require support in understanding the various research methods and their implications. The researcher may thus be required at act as a resource person at the research design stage (Drevdahl 1995). However, the community members can provide an important perspective on how the use of proposed methods may be experienced by participants. It is important that data collection methods which give community members a voice are explored (Tetley & Hanson 2000).

Data analysis is perhaps one of the most complex stages of the research process and this can give rise to some difficulties in participatory research projects. For example, Schneider et al (2004) note that, due to the cognitive difficulties associated with schizophrenia, participants in their study experienced problems with this stage of the research, particularly as they found it difficult to concentrate for long periods.

Beresford (2005) suggests that data analysis raises questions as to who is best placed to undertake this task, particularly when the data gathered are concerned with the experiences of those who use services. Are the service users themselves best placed or should professionals and academics undertake such a role since they can ‘claim distance’ from the experiences (Beresford 2005)? One of the strengths of participatory research is that members of the research team each bring to the project differing experiences and this can enrich the process of data analysis. For example, Koch et al (2002) note that, in their participatory research involving groups of community nurses, shared meanings emerged as the projects progressed, facilitated by the fact that participants were able to compare and contrast their own interpretations against those of other group members.

Reporting the research findings can take several forms from the traditional development and publication of papers for publication in academic and professional journals through to other forms of dissemination such as theatre presentations (Schneider et al 2004). Where papers are written for publication, ideally, they should be written in a collaborative manner (Ham 2004, Northway 2001 and Schneider 2004). However, if findings are disseminated only in professional and academic contexts there is a danger that the people whose lives are the focus of the research will not gain access to information which could help them. Findings should be disseminated more widely and in formats that are accessible to service users.

The nature of the action to be taken will inevitably differ from project to project and hence it is difficult to be prescriptive. One example involved making theatre presentations to health care staff concerning communication with people with mental health problems which resulted in some health professionals reporting a change in their perceptions and practice (Schneider et al 2004). In the study reported by Ross et al (2005), consumers involved in the project became involved in decision-making meetings with the Primary Care Trust. The nurses involved in one of the studies reported by Koch et al (2002) developed a video concerning the prevention of workplace violence which, combined with feedback from educational activities and discussion with management, resulted in the development of a model for best practice. What each of these examples has in common is that they each seek to address issues of concern to the community and to enhance quality of life.

The nature of knowledge produced

Khanlou and Peter (2005) argue that participatory research values ‘useful knowledge’, namely that which has some practical use. Park (1999) identifies three different forms of knowledge (representational, relational and reflective), each of which he suggests are typically developed in the course of a successful participatory research project.

Representational knowledge has two different forms – functional and interpretive. The former is concerned with the linking of variables and seeks to investigate cause and effect. The latter is concerned with understanding the meanings that humans give to events and experiences. Representational knowledge can thus be seen to encompass both quantitative and qualitative elements.

Participatory research, however, goes beyond these forms of knowledge typically generated in other research approaches. Members of the research team work together over a period of time and seek to investigate the conditions that shape their lives. As a result they come to know each other and their communities better. Park (1999) refers to the knowledge gained by such processes as relational knowledge, arguing that, whilst it is not a form of knowledge which is explicitly pursued, it is an outcome that is often valued by participants.

Park (1999) argues that participatory research is motivated by a vision of what should be. Reflective knowledge is thus that which results from people’s critical reflections concerning the difference between what is, what should be, and hence what needs to change. It is knowledge which motivates people to take action to produce such change.

Each of these three forms of knowledge ‘reinforce and interact with one another’ (Park 1999, p. 149). They can also operate at a variety of different levels. For example, the process of working together with others in the course of a participatory research project can lead researchers to reflect upon their own motivations, values and performance and take action to bring about personal change (Northway 1998b and Wahab 2003).

A different role for the researcher

Traditionally, researchers have been encouraged to take a detached and objective role. However, this is not the case in participatory research. Instead the researcher is expected to be a committed participant (Hall 1979), to challenge those processes which separate the researcher from the researched (Finn 1994); it has been suggested that being a participatory researcher is a vocation rather than a job (Park 1999).

Seng (1998) notes that, being accountable in the usual ways (e.g. to research funders and employers), participatory researchers are also directly accountable to the community with whom they are undertaking the study. The potential for tensions between these differing lines of accountability can thus be seen.

Stoeker (1999) has identified four key roles that may be required of the participatory researcher: animator (assisting people to develop a sense of important issues), community organiser (planning and organising the research activity), popular educator (facilitating learning during the research process) and participatory researcher. The demands placed upon the researcher will vary according to the stages of the research and according to the needs and abilities of the community. They thus need to demonstrate a high level of self awareness and reflexivity since such critical self-reflection enables them to examine their own values, motivations and actions (Northway 1998b) and hence to assume the most appropriate role at each stage.

Other requirements of the participatory researcher include good communication skills (Finn 1994, Koch 2002 and Ross 2005), the need for confidence and good organisational skills (Tetley & Hanson 2000), the ability to tolerate ambiguity (Finn 1994) and facilitation skills (Koch et al 2002). Given this wide range of demands, it is not surprising Drevdahl (1995) suggests the ‘enormity’ of such work can exhaust a lone researcher – physically and mentally. The need for ‘novice’ participatory researchers to receive mentorship has thus been suggested (Tetley & Hanson 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access