Chapter Six. Participation, involvement and engagement

Key points

• The context for public and patient involvement

• The context for community engagement

• Typologies of participation

• Patient and user involvement

• Participation in needs assessment and priority setting

• Community development, community engagement and capacity building

• Evaluating public involvement and community engagement

OVERVIEW

This chapter examines the growth of participation and involvement as key strategies in public health and health promotion. The concept of public involvement is not new, and international and national bodies have advocated participation since the 1980s. However, public participation is now increasingly being seen as relevant to improvements in service delivery, monitoring and management. The NHS Plan (DH 2000) envisaged a service which is shaped around the convenience and concerns of patients. Patient and public involvement (PPI) is carried out at the level of the individual, involving patients in decisions about care and treatment, and at the collective level, involving patients and the public in decisions concerning the planning and delivery of services. PPI therefore covers a broad range of activities from providing information to gathering feedback to involvement in decision making. Community engagement, especially with marginalized and seldom heard groups, is a key feature of public policy to reduce health inequalities. This chapter discusses some of the strategies which may be used to engage the public and service users. Finally, the chapter discusses the difficulties of evaluating participation and involvement strategies and concludes with a discussion of public involvement from the perspective of a health practitioner.

Introduction

There is no simple explanation of why public participation has become so significant in governmental discourse and practice in many countries in recent years. This paradigm shift, whereby the public are seen as co-producers of health, draws from social and patient rights movements (Brown and Zavestoski 2005). The Department of Health reflects this in naming its involvement section ‘Patient and Public Empowerment’. Popular neoliberal ideology (see Chapter 4) has recast the public as active consumers rather than passive recipients of services with new forms of governance of public services (Newman and Clarke 2009).

There is a broad spectrum of attitude and purpose in relation to ‘involvement’. The emphasis is now on participatory and bottom-up approaches (rather than control by experts) reflected in a range of actions including:

• User participation in decisions about treatment and care.

• User involvement in service development.

• User evaluation of service provision and a shift to public accountability.

• User involvement in teaching and training of practitioners.

• User involvement in research.

A commitment to a community-oriented health approach informs the UK government health and care programmes (see Chapter 4). NICE, the standard-setting body for the NHS, has set out guidelines for patient and public involvement (PPI) (see http://www.nice.org.uk/getinvolved/patientandpublicinvolvement/), and for commissioning organizations’ work with partners to engage communities in identifying their health needs and aspirations when developing strategic plans. This includes making sure community perspectives – people’s preferences, felt needs and expectations – are built into the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) and health needs assessments undertaken with particular communities, moving beyond a solely data-driven approach to needs assessment to one that is complemented by the views of those in the community. For example, Competency Three of the requirements for World Class Commissioning, the means by which the government aims to deliver high-quality services (DH 2007), states: ‘PCTs are responsible through the commissioning process for investing public funds on behalf of their patients and communities. In order to make commissioning decisions that reflect the needs, priorities and aspirations of the local population, PCTs will have to engage the public in a variety of ways, openly and honestly. They will need to be proactive in seeking out the views and experience of the public, patients, their carers and other stakeholders, especially those least able to advocate for themselves’.

‘Involvement’ is a principle across all health and social care sectors but is central to health improvement, and there are specific reasons why public health and health promotion practitioners may lead on this issue. Foundations for Health Promotion (Naidoo and Wills 2009) highlighted how the role of communities in health improvement has been signalled in key international agreements:

• Equity and participation were central concepts of the World Health Organization Health for All 2000 strategy.

• The Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) made community participation and strengthening communities a central principle and level of action for health promotion.

• The Jakarta conference on Health Promotion into the Twenty-First Century (WHO 1997) highlighted the need to increase community capacity and empower the individual as one of five priorities for health promotion.

PPI, empowerment and community engagement pose real challenges for practitioners. Although there have been moves to client-centredness in care, a professional service culture continues to be reluctant to let communities or users lead. The need to meet centrally imposed targets (see Chapter 4) means that the organizational ethos is very task-focused. To increase involvement means consciously reaching out and being proactive in enabling communities to play a real role in planning services and programmes. It means discovering a community’s health needs and priorities and then supporting and enabling them to improve their health. This involves uncertainty and giving up some aspects of power.

This chapter explores some of the challenges of PPI and community engagement:

• How users and communities can be involved in decision making about services and generating knowledge and evidence.

• How communities can be supported to deliver health improvement.

• How the professional service culture can be changed to acknowledge the importance of users and communities as partners in health improvement.

The context for PPI

A dictionary definition of ‘involvement’ is ‘to include’ or ‘to be part of’. The definition of participation is simply ‘taking part in’ and the definition of ‘empowerment’ is ‘to take control of’. Obviously encompassed within these definitions is the possibility of a variety of activities and outcomes ranging from someone merely being present at a decision-making forum to a form of empowerment whereby people have a real say in decisions and issues that affect their lives.

Why is involving people seen as a ‘good thing’?

Involving people:

• enables organizations to get a clearer idea of what is important to local communities

• identifies unmet needs

• enables resources to be targeted effectively and to prioritize future spending

• ensures that services will be used and are relevant for the local context

• improves quality through measuring satisfaction

• encourages people to feel a greater ownership and commitment to services and projects that they have been involved in designing and may help to restore confidence in public services

• contributes to greater openness and accountability.

The growth of participation can be traced through several parallel developments:

• The growth of the power of the consumer There is increasing attention given to service users in all public sectors. This can be traced back to a desire to reduce the role of the state and roll back paternalistic government. The construction of league tables of performance and charters have introduced the concept of minimum entitlement that indicates what users have a right to expect, and is used by government to make services more accountable.

• The growth of citizenship The World Health Organization identified the basic right of any citizen to participate in their health care and a ‘duty’ or ‘obligation’ to exercise that right in the Alma Ata Declaration (WHO 1978). As citizens, people have been encouraged to have a legitimate expectation to participate in decisions that affect them. Alongside rights come responsibilities. There is also therefore an expectation that citizens will use services appropriately and contribute to their own health improvement. This is reflected in the NHS Constitution for England (DH 2009, p. 7) which states: ‘You have the right to be involved, directly or through representatives, in the planning of healthcare services, the development and consideration of proposals for changes in the way those services are provided, and in decisions to be made affecting the operation of those services’.

• The lay voice In recent years, there has been a questioning of professional and policy assumptions about the best way of delivering services. There is an increasing recognition that the lay perspective gives insight into patterns of behaviour and lifestyles and subjective experiences. This understanding can help to ‘unpack’ global concepts such as health inequalities, and enable the development of appropriate and accessible services. There is a commitment to involving patients in the management of chronic conditions and valuing individual expertise developed through experience in the ‘Expert Patient’ initiative (DoH 2001a).

• Legislation The importance of listening to the public has been reinforced by several inquiries including the Kennedy report on the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry (DH 2001b), which recommended that the perspectives of patients and of the public must be heard, be taken into account and permeate all aspects of health care.

These different terms, although sometimes used interchangeably, denote different levels of power. Consumers and users have limited power to affect services. Their ultimate sanction is to refuse to use services, and take their custom elsewhere. The terms originate in an economic model of relationships within capitalism, and the relevance of such terms to universal state service provision has been questioned. Most people cannot afford the alternative of private sector services, although the UK government has encouraged the notion of competition and ‘shopping around’ within the state sector for services. The concept of citizenship implies a more active engagement and use of power to determine the kinds of services offered. Citizens hold power, even if at several removes, through the democratic process, and services need to be accountable to citizens. The term ‘lay people’ suggests an intermediate level of power between consumers and citizens. Lay people hold local lay knowledge, but lack expert professional knowledge. Lay people are therefore vital partners if services are to develop in appropriate and accessible ways.

Internationally, public health planning has tended to be a top-down process based on expert identification of priorities and strategies and donor agencies financing piecemeal health projects. People living in low-income/developing countries often consult an array of practitioners and there are few safeguards and little monitoring of providers. Households may also make substantial contributions to health activities in cash and in kind. Many governments have tried different forms of decentralization such as district management boards and local health committees. Such structures can provide a means whereby local voices, particularly those of poor people and women, can be represented. However, Greenhalgh (2009) uses the example of patient activism in South Africa to point out the naivete of narrow views of participation. Obtaining AIDS treatment at all has been a political struggle of far greater importance than patient involvement and self-management.

Participation in healthcare planning

In a remote rural area of China, the maternal mortality rate and infant mortality rate were much higher than the national average. A loan from the World Bank intended to improve maternal and child services stipulated that the poorest families should be allocated money from the loan to enable them to access ante- and postnatal care, hospital deliveries for emergency or high-risk pregnancies, and treatment for infant pneumonia and diarrhoea. But 99% of women continued to deliver at home attended by an untrained person, some counties did not spend the money, and some used it only for obstetric emergency care. A participatory planning workshop was attended by all the major stakeholders (service providers at province, district, county, township and village levels; health officials and managers; township leaders). The priorities for the loan were identified and concerns shared about its administration – that it should not be used all at once; the inability to encourage the poor to access the fund; that the limited money should be used on emergencies only; that the limited money should be used on infant disease treatment rather than maternity care. As a result of the workshop, the project was able to ‘correct’ the misuse and underuse of the funding and ensure that the project became sustainable.

The context for community engagement

The discourse of community is pivotal to the policy agenda of the past decade and a plethora of policies.

The ‘community’ is seen as the site where needs are both defined and met. The public health White Paper ‘Choosing health: Making healthy choices easier’ refers to how ‘the environment we live in, our social networks, our sense of security, socio-economic circumstances, families and resources in our local neighbourhood can affect individual health’ (DH 2004, Ch. 4). Policy initiatives have attempted to address many of the characteristics of the community: There has been a raft of regeneration initiatives intended to transform the country’s most deprived and excluded areas. There is recognition in policy that the sense people have of community is also forged through everyday societal interactions and networks of friends, families and neighbours. Health inequalities are now clearly linked with the concept of social exclusion, the latter being defined as:

‘What happens when individuals or areas suffer from a combination of linked problems such as unemployment, low incomes, poor housing, a high crime environment, poor health and family breakdown’ (www.socialexclusion.gov.uk). The concept of social inclusion in which everyone, whatever their circumstances, is encouraged to make use of opportunities to participate in society, has permeated policy. The English government Department for Communities and Local Government (www.communitiesgov.uk) is responsible for, among other things, building sustainable communities, neighbourhood renewal, and tackling anti-social behaviour (see, for example the White Paper ‘Stronger and prosperous communities’ (Department for Communities and Local Government 2006); and recent public service agreement targets outlined in ‘Building more cohesive, empowered and active communities’ (HM Treasury 2007)). Working with and for communities through community development has now ceased to be seen as experimental and radical but much more mainstream in policy and service delivery and a vital public health function.

In part, community engagement means people have opportunities for participation in all sorts of decisions in their lives, whether it is their choice of treatment or place of schooling, and it is assumed that by being involved, people are more likely to get the services they want and need. A more cynical view might see this as a strategy of governance of the public that seeks to encourage self-dependent responsible citizens who take care of their own welfare. By seeking to engage marginalized groups, individuals are connected with a plurality of networks which it is assumed will help overcome social fragmentation and the alleged breakdown of parenting and families. People will therefore rely on each other rather than the state.

Understanding involvement and participation

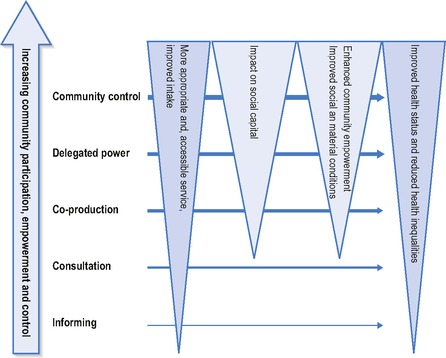

Recent guidance on the evidence supporting community engagement (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008a and National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008b) proposes a theoretical framework (see Figure 6.1) that outlines why different levels of community engagement could directly and indirectly affect health in both the intermediate and longer terms. The framework proposes that those community engagement approaches used to inform (or consult with) the public may have an impact on the appropriateness, accessibility and uptake of services. Approaches that help communities to work as equal partners (co-production), or which delegate power to them may lead to more positive health outcomes which may also include enhancing their identity as a community.

|

| Figure 6.1 • Community engagement for health. |

The guidance suggests this may arise because these approaches:

• utilize local people’s experiential knowledge to design or improve services, leading to more appropriate, effective, cost-effective and sustainable services

• empower people by, for example, giving them the chance to co-produce services: participation can increase confidence, self-esteem and self-efficacy (i.e. a person’s belief in their own ability to succeed). It can also give them an increased sense of control over decisions affecting their lives

• build more trust in government bodies by improving accountability and democratic renewal

• contribute to developing and sustaining social capital (social support networks)

• encourage health-enhancing attitudes and behaviour.

(Attree and French 2007 cited in National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008a and National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008b).

The NICE guidance reflects the struggle to bridge the conflicting paradigms of evidence-based practice and values-based practice (see Chapter 3). NICE recognizes that evidence of the effectiveness of community engagement strategies may simply not be possible as ‘research in this area has often been the result of haphazard and unrelated decisions by both funders and researchers’ (p. 12) and ‘community-based activities are difficult to evaluate because of their complexity, size, the speed of rollout, their (usually) limited duration and the multiple problems they try to address’ (p. 12). Yet the NICE guidance asserts that community engagement is desirable practice.

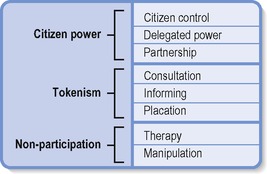

The framework described above suggests that there are levels of participation. Several writers have developed typologies of participation (e.g. Arnstein, 1969 and Wilcox, 1994). These models make a hierarchical distinction between approaches to involvement according to the amount of power sharing involved and the degree of influence over decisions. Arnstein’s (1969) model, shown in Figure 6.2, is presented as a ladder where the lower rungs are participation activities designed to give people a voice as a way of making them involved but they remain recipients of services and there is little commitment to them having real influence. The next rungs are about consultation activities that seek to identify with communities and find out what is needed and listen to views before decisions are made. The higher rungs of the ladder identify forms of participatory activity in which the community has greater power and influence and there is a commitment to integrating their views in wider processes. The top rung is user-led activities in which agencies step back from the identification of priorities or the definition of solutions and help communities to do what they want.

|

| Figure 6.2 • Ladder of participation. Source: Arnstein 1969. |

Arnstein’s model has been criticized as a simplistic rationalization, but it has enjoyed considerable currency as it was the first to put forward the idea of establishing a structured framework of engaging a community and using consultation within the planning/participatory framework of decision making. Models of participation that are presented as hierarchies imply that projects should aspire to the highest level; yet participation needs to be appropriate to its context and take account of the issues involved.

A further major challenge for organizations and practitioners is to create opportunities for people to be involved. In some situations it may be sufficient to inform or consult while in others the principle of partnership and working with communities is important.

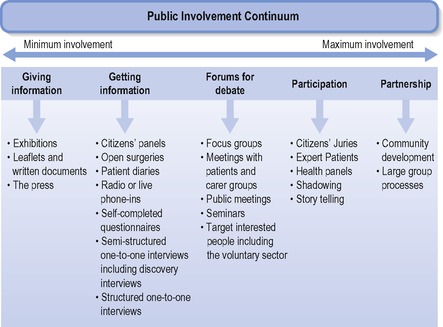

In Figure 6.3, the main dimensions of involvement are seen at the level of the individual, involving patients in decisions about care and treatment, and at the collective level, involving patients and the public in decisions concerning the planning and delivery of services. Possible aims and objectives for local PPI may be to:

• get feedback on the quality of services

• learn more about patients’ experiences of care

• identify unmet needs

• gain ideas about priorities.

We carried out a consultation exercise with the local community about whether to set up a new health centre that would act as a local resource for advice, exercise and complementary therapies.

We held a public meeting that we advertised in the local press, community centres and libraries and in shops. About 200 people came. We then met with 23 local groups and held 6 focus groups of local people. We carried out a street survey. We also took comments in writing, on a website and in telephone calls and there were about 2000 of these. There was no problem getting a response and enormous efforts were made with the modes of communication and language.

If I were being cynical I would say that despite the number of responses, we had to be seen to be consulting. I think it was just a means of getting an existing decision across and getting public support made the case more powerful. Lots of people in the focus groups seemed to think the decision had already been made and there would not be a response to their concerns.

Commentary

Involvement in decision making is part of a new thrust to enable patient and public to engage with health services. Frequently such efforts are tokenistic and the scope for responding to views is limited. Harrison and Mort (1998) argue that involvement is frequently used as a way of legitimizing corporate decisions or ‘placation’ on Arnstein’s ladder. There may be a lack of openness about any decisions to be taken and the professional expectations from any consultation. Users and carers may then become cynical about the value placed on any consultation.

|

| Figure 6.3 • Levels of involvement (from DH 2003). |

As much as the challenges of transferring power, public involvement also poses the challenge of ensuring that decisions are representative of a public view. The current drive for ‘involvement’ refers to ‘patients’ and ‘public’. These terms have been criticized. Those who use services may not identify themselves as patients or users and view their involvement as time-limited and condition-specific. The term ‘user’ implies independence, but as Ovreteit (1996) states, ‘it gives the impression of someone exploiting the practitioner and does not advance the idea of partnership’.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access