Chapter 35 PAIN MANAGEMENT

Pain may be mild or severe, acute or chronic. Pain is difficult to define, as it is an individual experience with varying levels of intensity, and it may be physical, psychological or emotional in origin. Pain is often described as being a sensation of distress or suffering caused by a particular stimulus. A definition of pain that has been widely accepted and used by many nurses is that of McCaffery, a highly recognised pain care specialist (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). Her definition encompasses the idea that ‘pain is what the person says it is, and exists when he [sic] says it does’. Pain is increasingly being considered a condition rather than a symptom, and ideas about pain and its management are constantly changing.

PHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN

Pain is one of the most common causes of discomfort, and pain avoidance is viewed by Maslow (in Crisp & Taylor 2005) as a first priority physiological need. Pain avoidance appears to be an instinctive reaction to harmful factors in the environment; for example, a newborn will draw away from a painful stimulus. Throughout the life cycle, people will avoid painful stimuli or take actions to withdraw from such stimuli. The ability to relieve or to control pain depends on an understanding of how it occurs and how it is controlled by the brain. The physical experience of pain can be divided into four distinct phases: the stimulus which causes the pain, the transfer of pain, the perception of pain and the reaction to pain.

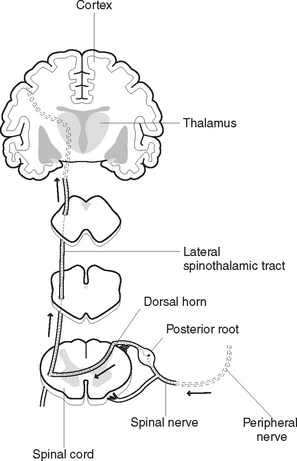

When pain receptors are stimulated they send electrical impulses along special pathways to the spinal cord. These pathways may be seen as being similar to a two-lane road, one lane with large diameter fibres for fast message transmission (‘A’ fibres), and one lane with smaller diameter fibres for slower message transmission (‘C’ fibres). ‘A’ fibres have the most insulation, and carry information that reflects throbbing and pricking types of pain. Slow pathways (‘C’ fibres) have less insulation, and carry impulses that represent burning pain. Pain receptors in the skin and other tissues are free nerve endings, some of which are the peripheral terminations of small diameter ‘C’ fibres, while others are the slightly larger diameter ‘A’ fibres. When histamine and other naturally occurring chemical substances are released as a result of tissue damage, pain sensations travel along the nerve fibres. Regardless of the type of pain, and whether travelling slowly or quickly, pain impulses are transmitted to the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, where they synapse with certain neurons in the posterior horns of the grey matter. Pain sensations are then transmitted to various areas of the brain by synapses at the thalamus, where they are perceived and interpreted (Figure 35.1).

Although the complex mechanisms of the physiology and psychology of pain are not understood completely, there are several theories of pain. The gate-control theory of pain (Melzack & Wall 1965) suggests that neural mechanisms in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord can act like a gate. This theory suggests that activity in the large diameter nerve fibres can close the gate and block pain impulses, resulting in a decrease or elimination of pain sensation. Therefore, according to this theory, it is possible to block pain impulses travelling to the brain by stimulating the large ‘A’ nerve fibres and ‘closing the gate’. This theory may help to explain the reason why cutaneous stimulation (rubbing a sore spot) or acupuncture can relieve pain, as in acupuncture, stimulation of non-painful nerve fibres can ‘confuse’ messages and suppress pain signals.

CAUSES OF PAIN

Pain is often a useful protective signal, as it can be a warning of actual or impending tissue damage. The sensation of pain can also warn the individual of emotional or stress-related problems, such as a headache caused by tension or anxiety. Pain can result from many sources or stimuli, including mechanical trauma, chemical irritants, extremes of temperature, ischaemia and psychological factors.

TYPES OF PAIN

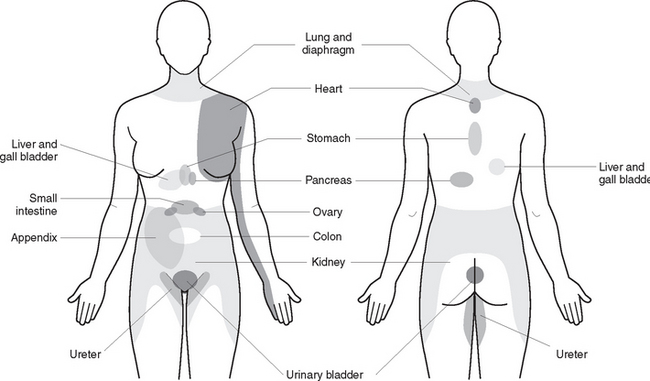

Visceral pain may be felt at a site far removed from the affected area, through the mechanism known as referred pain. Referred pain is felt in a part of the body away from the pain’s point of origin; for example, pain in the left shoulder and arm associated with myocardial infarction. In this instance, sensory neurons that transmit signals from the skin enter the same area of the spinal cord as do nerve fibres from the myocardium. The neurons carry pain signals from both areas to the brain and, because cutaneous pain is more common than visceral pain, the brain interprets the pain as originating in the skin. Figure 35.2 illustrates the common sites of referred pain in a female, but it can be noted that the sites are the same in both females and males.

Total pain, the experience of a person with an ongoing pain syndrome, is derived from several sources. The term ‘total pain’ has been devised to address the complexity of pain as both a somatic and a psychological experience. It has been well documented that a person’s pain threshold can be lowered by psychological factors such as fear, depression and isolation, with the result that the pain experience is increased.

PERCEPTION OF PAIN

The perception of pain is individual and is therefore different for each person. In addition, a person may perceive pain differently at different times. Clinical Interest Box 35.1 provides some common biases and misconceptions about pain. The pain threshold is the point at which a stimulus, such as pressure, activates pain receptors and produces a sensation of pain. Four identifiable levels of pain threshold have been described:

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.1 Common biases and misconceptions about pain

The following statements are false:

FACTORS INFLUENCING PAIN

Age

The ability to tolerate pain generally seems to increase with age, and this may be partly due to expectations about what constitutes ‘adult’ behaviour. Many myths also exist, however, in relation to pain experienced by older adults, particularly those with cognitive impairment. This has resulted in an underestimation and management of pain in people with disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical Interest Box 35.2 provides more information about pain management in clients with Alzheimer’s disease. Common misconceptions include that pain is a natural consequence of growing old, that pain perception decreases with age, and that, if the older adult does not report pain, they do not have pain.

Culture

Cultural values, attitudes and feelings contribute to the way people react to pain. Some people have a matter-of-fact attitude to pain, with little outward expression of their suffering, while others are more expressive and seek immediate pain relief. Most Western cultures place strong values on the ability to bear pain with silent fortitude, so that external behaviours may not reveal the intensity of pain. People from Latin cultures are permitted to display their suffering openly, such as by crying or moaning, as a socially accepted response to pain. It must also be appreciated, however, that there are enormous differences within every culture and that not every person from a specific culture will react in the same manner. Clinical Interest Box 35.3 provides an example of a cultural experience of pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree