Chapter 44 Pain management

INTRODUCTION

Pain is one of the most common experiences a child will have as a result of injury, illness or medical procedures. Pain is associated with anxiety, fear, stress and distress for the child and their family. The subjectivity and multidimensional experience of pain makes it inherently difficult to assess, particularly in children, who often lack the verbal or cognitive ability to express their feelings of pain (Gaffney et al 2003). However, pain assessment is essential, not only to detect pain but to evaluate the effectiveness of our pain management interventions if we are to provide optimal pain control (Howard 2003; Finley et al 2005).

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section you should be able to:

RATIONALE

The treatment and alleviation of pain is a basic human right that exists regardless of age (Schechter et al 2003). The consequences of untreated pain include a delay in mobilisation, psychological trauma, an increase in the risk of infections, slower recovery and a delay in discharge from hospital. The undertreatment of pain in children is evident in the literature (Wilson & Doyle 1996, Nikanne et al 1999, Van Hulle 2005, Stinson & McGrath 2007); however, over the past two decades, there has been growth in the quantity and quality of paediatric pain research evidence. This evidence has advanced our understanding of the physiology and management of pain in children. In 1993, in a publication entitled Children First: A Study of Hospital Services, the Audit Commission (1993) identified pain relief as an indicator for measuring quality of care for children in hospital. More recently, the National Service Framework for Children has outlined standards for managing pain in hospital (DoH 2003). Assessment of a child’s pain is problematic but it is essential if we are to provide effective management and therefore it must be an integral part of our nursing care.

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

GUIDELINES

The purpose of pain assessment is to provide as complete a picture as possible of a child’s pain (Box 44.1).

Good pain assessment contributes to the prevention and/or early recognition of pain as well as the effective assessment of pain (Finley et al 2005).

The family has an important role to play in ensuring that a child’s pain is managed effectively (Liossi 2002). Where the situation permits, this involves determining a child’s past pain experiences and whether these were good or bad. Children may use a variety of words to describe pain and these should be identified prior to potentially painful experiences (RCN 1999). A description of the child’s behaviour, which would normally indicate the presence of pain should be sought from the parents. The family may already employ certain coping strategies; these, along with analgesics used at home, should be discussed. Parents can also be helpful in identifying the pain assessment scale that may be appropriate for their child. Parents can be a particularly valuable resource with children with complex needs. A variety of pain assessment tools are available to help guide the professional to assess the pain in this group of children (RCN 2001, Voepel-Lewis et al 2002). These children may be unable to articulate or express their pain verbally or behaviourally. Carter et al (2002) found that parents used various strategies to identify their child’s pain based on their in-depth knowledge of their child. The identification of this skill is also supported by findings from a study by Stallard et al (2001).

It is vital that the nurse receives appropriate levels of education, training and preparation in the use of pain assessment tools and proficiency in using them (Treadwell et al 2002; Malviya et al 2006). The nurse’s assessment of children’s pain is subject to a range of individual bias, social, and contextual influences This is particularly important to note when caring for children who are too sick to use self-reporting scales, neonates/infants and children with special needs. Professionals need to be flexible and willing to develop more positive attitudes and beliefs regarding the attributes of children’s pain (Salantera et al 1999). Pain assessment should be part of a holistic approach to the child. The nurse should be able to take the information provided by the child and interpret it with skill. For example, a report of pain described in a particular manner may indicate a full bladder and urinary retention rather than wound pain. This should be treated in a different way and it is important, therefore, that the information given is channelled correctly.

It is also vital that children who can comprehend the pain scale and self-report are made aware that if they are in pain the treatment of that pain is patient friendly. A self-report is the only truly direct measure of pain and is often considered to be the ‘gold standard’ of measurement. Pain assessment is the most accurate when children can describe their pain in an appropriate manner and relevant language for their age and development (Broome & Huth 2003). However, for certain patients this will not be possible.

FACTORS TO NOTE

Culture

It is accepted that culture can influence an individual’s perception and response to pain (Bates 1987). However, over the years, most of the studies looking at culture have been in relation to adults (Bernstein & Pachter 2003). Recommendations have been made which suggest we should recognise the importance of cultural factors which affect the assessment of pain in children (RCN 1999). It is important that, while being aware of cultural differences in pain expression, we should try to avoid stereotyping (Bernstein & Pachter 2003).

Neonates

Neonates cannot communicate by verbal report, so they are dependent on caregivers to recognise that they are in pain. Physiological and behavioural signs must be observed and interpreted as an indication of pain being present. A variety of scales have been made available for neonates, taking into consideration physiological and behavioural factors such as facial expression, crying, body position, body movement, colour, oxygen saturation (SaO2), respiratory rate, blood pressure and heart rate (Hodgkinson et al 1994, Krechel & Bildner 1995, Ghai et al 2008). However, it should be noted that these observations can be affected by a variety of factors as well as pain, such as ventilatory support, drugs and the neonate’s clinical condition. The scales that take this into consideration may be more accurate (Sparshott 1996).

Children (pre-school to 7 years)

Studies have shown that many 3 year olds can identify the presence and absence of pain and can report a pain intensity (Harbeck & Peterson 1992, Romsing et al 1996). It is recommended that the choice of pain intensity scores for this age group should be limited to around four choices. They can usually verbalise in appropriate language, to the nurse or their parents, a description of ‘their hurting’. It is important to remember that younger children may choose extremes of measurement and some may even confuse the scales with measurements of happiness. Some children in this age group may experience behavioural disturbances due to the trauma of hospital admission. Regression to earlier stages in development, such as loss of speech, clinging to parents or a return to bed wetting, may be noticed. Aggression may be a form of identifying pain. Children may be in pain but unable or reluctant to indicate that it is present. Their behaviour becomes aggressive as a response to this pain. It is important that nursing staff can recognise this and educate parents of this response.

CONDUCTING A PAIN ASSESSMENT

History taking

Documentation of pain assessments should occur and guidelines recommend that they be recorded on the routine observation chart (Royal College of Surgeons and the College of Anaesthetists 1990). This is important because there is evidence to suggest that accurate documentation increases the assessment of pain, administration of analgesia and improved pain management (Savedra et al 1993, Goddard & Pickup 1996, Treadwell et al 2002). For postoperative pain, for example, a pain scale should be used to assess a child’s pain with the routine postoperative observations, decreasing in frequency as the observations decrease but more regularly if a child is complaining of pain or analgesia has been administered.

Pain assessment scales usually incorporate one or more of the following:

Behavioural assessment

Behaviour is one of the first indicators that alerts caregivers to the presence of pain (Reaney 2007). It involves looking at how a child behaves in response to pain. Types of distress behaviour, e.g. facial expression, cry and body movements, have been associated with pain. However, difficulties include differentiating this behaviour from behaviour that results from anxiety or hunger (Gaffney et al 2003).

Behavioural pain assessment has some advantages in that it is non-invasive, does not put any demands on the child and does not depend on their cognitive ability or language skills. Assessment of behavioural signs could indicate the presence of pain and help determine the effect the pain is having on the child or infant (Table 44.1).

Physiological assessment

Physiological signs vary greatly, particularly in premature infants (Stevens et al 1996).

Different parameters have been examined, including:

There is a debate surrounding the reliability of using physiological signs to determine the presence of pain (Carter 1994). There is in fact insufficient evidence to suggest that physiological signs are directly related to the pain experienced. Like behavioural responses, physiological responses can be affected by many things, resulting in problems of interpretation.

Self-report techniques

As pain is a subjective experience, self-reporting techniques are acknowledged as the most accurate indicators of pain (Broome & Huth 2003); however, they rely on children having the relevant language for their age and development and the ability to describe their pain in an appropriate manner. It must be remembered that a child’s self-report of pain may be affected by contextual factors or concerns regarding the pain-relieving interventions that may be offered.

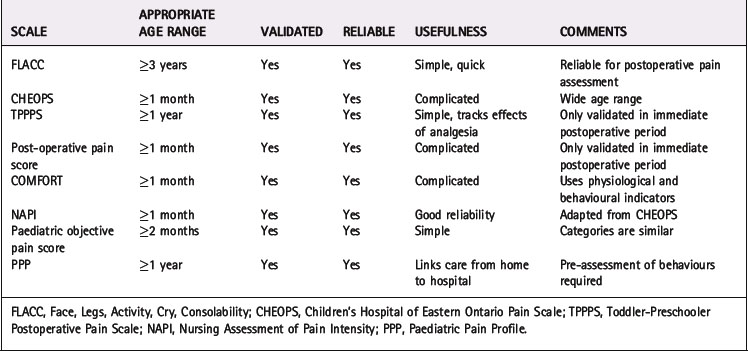

For many years there has been agreement that multidimensional assessment is essential. Stinson et al (2006) suggested that no individual behavioural, self-report or physiological measure is recommended for pain assessment across all children or all contexts. They suggested that healthcare professionals need to make informed choices about which tool to use to assess each individual child’s individual pain (Table 44.2, Fig. 44.1). A well-established approach that takes these factors into account is QUESTT (Baker & Wong 1987):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree