In addition to the physiologic factors that influence the perception of pain, psychosocial factors influence an individual’s experience. These factors include labor support, childbirth preparation, and the healthcare environment.

LABOR SUPPORT

Women identify labor support as a continuous presence by another, emotional support (reassurance, encouragement, and guidance), physical comforting, providing information, and guidance for the woman and her partner regarding decision making, facilitation of communication, anticipatory guidance, and explanations of procedures (

Simkin & Bolding, 2004;

Roberts et al., 2010). Providing for physical comfort includes offering a variety of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions. Emotional support includes behaviors such as giving praise, encouragement, and reassurance; being positive; appearing calm and confident; assisting with breathing and relaxation; providing explanations about labor progress; identifying ways to include family members in the experience; and treating women with respect (

Bryanton, Fraser-Davey, & Sullivan, 1994;

Sleutel, 2000). Methods of labor support are found in

Display 16-1.

REGISTERED NURSE

It is the position of the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) that supporting and caring for women during labor is best performed by a registered nurse (

Display 16-2). Comprehensive nursing education, clinical patient-management skills, and previous experience make the registered nurse uniquely qualified to provide the professional care and complex emotional care women and families need during labor and birth (

AWHONN, 2000). The perinatal nurse must be able to support the laboring woman and assist her in maximizing the potential of the woman’s birth plan. Multiple strategies may be necessary during the course of labor. Perinatal nurses should develop expertise in a variety of pain-management strategies.

Nurses may spend anywhere from 12.4% (

Gale, Fothergill-Bourbonnais, & Chamberlain, 2001) to 58% (

Miltner, 2002) of their time providing supportive care to patients, usually doing so in conjunction with some technical activity. Factors that have contributed to individual nurses spending less time with women include increased technology associated with giving birth, increased requests for epidural anesthesia, and institutional staffing patterns. As use of technology has expanded in obstetrics, the perinatal nurse has moved from providing hands-on comfort to monitoring the equipment, imputing data into the electronic medical record and relying on pharmacologic interventions. Technology, especially when coupled with epidural analgesia, requires the nurse to divide her focus between the woman and machines. If pharmacologic methods have been used, the woman’s pain may be lessened and the nurse may feel that her presence is no longer needed. The nurse may perceive that caring for a woman with an epidural is less physically and emotionally draining for the nurse than caring for a woman who is planning nonpharmacologic management. If the culture of the perinatal unit allows ease of access to neuraxial analgesia, nurses new to the specialty will have limited opportunity to learn about or use nonpharmacologic measures.

It is important that the nurse recognizes the value of her presence and not be distracted by the technology. The registered nurse who understands the physiologic events of labor and has been educated about supportive care in labor should take the lead in providing

labor support and role model labor support behaviors for others present during labor and birth. Perinatal nurses should remain at the bedside when women are experiencing severe pain. This allows the nurse to provide support to the laboring woman and her partner. According to

Chapman (2000), nurses who remained at the bedside, explained what was occurring with the labor, and included the expectant father were viewed by those fathers as providing the most support.

HUSBAND OR SIGNIFICANT OTHER

Labor support ideally is provided by a variety of individuals (

Table 16-2). Qualitative research has demonstrated that one of the most significant aspects of the experience of labor for women is the presence of one or more support persons (

Lavender, Walkinshaw, & Walton, 1999). Postpartum women report that one of the things contributing to a positive labor experience was the presence of a family member or friend in the room even if “they just sit there” (

Lavender et al., 1999). At the time of admission, the laboring woman should identify family members or friends who will act as labor-support persons.

Fathers have an important role in providing physical and emotional support during childbirth.

Chapman (1992) described three roles assumed by expectant fathers during labor without epidural analgesia or anesthesia:

Coaches actively assisted their partners during and after labor contractions with breathing and relaxation techniques. Coaches led or directed their

partners through labor and birth and viewed themselves as managers or directors of the experience.

Teammates assisted their partners throughout the experience of labor and birth by responding to requests for physical or emotional support or both. They sometimes led their partners, but their usual role was that of follower or helper.

Witnesses viewed themselves primarily as companions who were there to provide emotional and moral support. They were present during labor and birth to observe the process and to witness the birth of their child.

These roles were identified by organizing behaviors that partners were observed performing during labor or behaviors women described in interviews after birth. Most men in the study adopted the role of witness rather than teammate or coach (

Chapman, 1992).

Chandler and Field (1997) report that witnessing their partners in severe pain caused men to feel helpless and fearful. They became discouraged when the comfort measures they tried did not help their partners. Ultimately, they felt they had failed in their role. These results contrast with the intentions of childbirth educators, who perceive themselves as preparing coaches and teammates for laboring women, and with perinatal nurses, who expect fathers and other family members to take a more active role in labor support.

The theoretical experience of expectant fathers when their partners received epidural analgesia or anesthesia is outlined in

Display 16-3 (

Chapman, 2000). During labor, critical experiences for men occurred at two points. In the holding-out phase of labor, before making the decision to receive an epidural, men experienced a sense of “losing her.” As pain became more severe, women underwent personality changes, becoming frustrated, irritable, exhausted, and panicky. These personality changes may be totally unfamiliar qualities that the men had never seen their partners demonstrate or demonstrate to the degree that they do while in labor. Women also gradually turn inward as they attempt to cope with the pain. Withdrawing into themselves causes women to be unable to communicate their needs and to become unresponsive to their partners’ attempts at labor support. Men feel increased levels of anxiety, helplessness, frustration, and emotional pain (

Chapman, 2000). These findings are consistent with the work of

Somers-Smith (1999), who found that fathers experience childbirth as a stressful event.

The second and most dramatic phase for men sharing the experience of labor is during the cruising phase. After the epidural has provided relief from the pain of labor, men describe a sensation of “she’s back.” The laboring woman again is aware of her surroundings and is interacting with those around her. From a man’s perspective, labor has gone from a stressful event to a calm experience. Rather than describing their experience in terms of the role they assumed during labor and the frustration and disconnected feelings they had as labor intensified and women’s behavior changed (

Chapman, 1991,

1992), these men described their experience by the degree of frustration they felt before the epidural and the degree of enjoyment after the epidural (

Chapman, 2000). It is important that childbirth educators present this content, discuss this process, and teach men in their classes about the emotions they can expect to witness and experience during labor.

DOULA

There is increased interest in the role of the professional or lay labor-support person (doula), who is present during labor in addition to the perinatal nurse. The movement toward professional or lay labor support is a result of the inability of perinatal nurses to provide women with the support they want during labor and the recognition that husbands or significant others do not always make the best coaches during labor. Being in a hospital and seeing one’s wife in labor may be very stressful for some fathers (

Klaus, Kennell, & Klaus, 2002). Childbirth education programs have traditionally provided training labor-support persons. However, the assumption that the husband or significant other makes the best coach may not be accurate (

Chapman, 1992). It is important for the father of the baby to be present during the labor and birth, but the presence of a doula may be what the laboring woman needs.

Labor-support persons, or doulas, with a variety of credentials and levels of education, assist women and their partners during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period. “A doula is a supportive companion (other than a friend or loved one) who is professionally trained to provide labor support” (

Gilliland, 2002, p. 762). Most often seen during labor, their main goal is to ensure that the woman feels safe and confident (

Ballen & Fulcher, 2006). A doula remains continuously at the side of the woman to provide emotional support and physical comfort (

Klaus et al., 2002). While not provided by all programs, a unique aspect of the doula role occurs postpartum, usually after discharge from the hospital. During a home visit, the doula is able to make time to review with the new mother her labor and birth experience with the goal of creating a satisfying birth experience. “The doula allows the woman to reflect on her experience, fills in gaps in her memory, praises her, and sometimes helps reframe upsetting or difficult aspects of the birth” (

Ballen & Fulcher, 2006, p. 305).

Table 16-3 contrasts the role of a doula with that of the perinatal nurse.

In a meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials in which continuous support by a doula was compared with traditional intermittent support of a labor and delivery nurse, continuous support was associated with significantly shorter labors; decreased use of analgesia, oxytocin, and forceps; and decreased cesarean births (

Scott, Berkowitz, & Klaus, 1999). In a culture in which women experience traditional labor without their husbands, those accompanied by a female support person had significantly shorter labors, less use of analgesia and oxytocin, and fewer admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (

Mosallam, Rizk, Thomas, & Ezimokhai, 2004). Women who had the benefit of a doula during labor expressed significantly less emotional distress and had higher self-esteem at 4 months postpartum than women who had attended a traditional Lamaze class (

Manning-Orenstein, 1998). When low-income pregnant women were randomized to be accompanied in labor by their family and a trained doula or just family members, those in the experimental group had significantly shorter labors and greater cervical dilation at the time of epidural anesthesia (

Campbell, Lake, Falk, & Backstrand, 2006).

Doulas (also known as labor assistants, birth companions, labor support specialists, professional labor assistants, and monitrices) may be volunteers or paid and are available through a variety of programs, either hospital based, community based, or as a private, contracted service. Hospital- and community-based programs are often available to underserved populations, women who may be newly emigrating, or women who might be alone during childbirth (e.g., adolescents, incarcerated women). Individual hospitals or community-based healthcare agencies may be involved in training doulas, or there are national organizations where training and certification are available (

Display 16-4). Services of a doula are generally arranged by the expectant couple or presented as an available option by a healthcare agency before labor.

The husband or significant other, family members and friends, and/or a doula should be welcomed and encouraged to provide labor support. The presence of one or all of these additional individuals does not decrease the ultimate responsibility of the perinatal nurse but instead adds to a positive birth experience. Labor support, when provided by nursing personnel, a partner, family members, or friends, affects a woman’s perception of labor (

Lowe, 2002;

Wright, McCrea, Stringer, & Murphy-Black, 2000). In a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials, continuous support from a nurse, CNM, or lay person resulted in decreased operative vaginal birth, cesarean birth, 5-minute Apgar scores less than 7, and use of medication for pain relief (Hodnett, Gates, Hafmeyr, & Sakala, 2003). In a systematic review of the literature, Hodnett (2000) found the attitudes and behaviors of caregivers are a stronger influence on satisfaction with childbirth than many other factors. Women who received continuous support during labor are less likely to request intrapartum analgesia, require an operative birth, or report dissatisfaction with their childbirth experience (Hodnett et al., 2003).

CHILDBIRTH PREPARATION

An awareness of the childbirth preparation and skills that the woman and her partner are prepared to use are helpful when planning nursing support strategies during labor. The desire for pain relief during labor varies in women with a spectrum from natural childbirth to the most invasive technique (e.g., neuraxial analgesia). Prenatal education should provide information on an assortment of pain management and coping skills to hopefully meet the expectations of the woman. Most pregnant women have concerns about labor process and their ability to handle painful contractions. Childbirth classes provide an opportunity to help women understand and let go of fears about labor and birth and begin to develop confidence in their ability to give birth. Antenatal education in preparation for childbirth is available in a number of formats including in a classroom, online, and through video display. Content and bias varies depending on the author and presenter of the material. Both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain relief methods may be presented as alternatives or complimentary to each other, which may influence the woman’s coping ability and choice. The common goal of all birthing classes is to provide the knowledge and confidence to give birth and to make informed decisions. Anxiety-reducing strategies and a variety of coping techniques integrated into the physiology of the birth process will provide an aid to pain management. Guidelines from 2008 from the National

Institute for Clinical Excellence (

NICE; 2008) reviewed studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia and recommend preparation for labor and birth to include information about coping with pain in labor and the birth plan. Knowledge regarding pregnancy, birth, and parenting issues is increased following attendance at antenatal classes, and the wish to receive this information is a strong motivator for attending classes. Classes need to include information about decision making, including both informed consent and the women’s right to an informed refusal. For the woman, it takes courage and confidence to communicate effectively with the healthcare team and her provider in making clear her expectations of labor and birth (

Lothian, 2005).

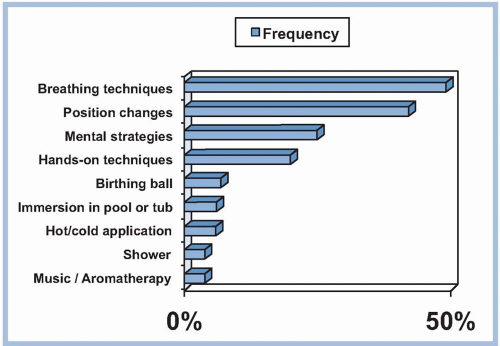

A broad range of nonpharmacologic behavioral strategies including controlled breathing, relaxation, positioning, and massage are usually presented in both the Lamaze and Bradley courses (

Table 16-4). The Lamaze® philosophy, also known as psychoprophylaxis, teaches that birth is a normal, natural, and healthy process. The goal of Lamaze® is to explore all the ways women can find strength and comfort during labor and birth. It is based on the Pavlovian concept of conditioned reflex training. Classes focus on relaxation techniques, but they also encourage the mother to condition her response to pain through training and preparation. This conditioning is meant to teach expectant mothers constructive responses to the pain and stress of labor as opposed to tensing muscles in response to pain. The basis of Lamaze® childbirth preparation is the belief that pain during childbirth leads to fear and tension, which increases the experience of pain. As fear and anxiety heighten, muscle tension increases, inhibiting the effectiveness of contractions, increasing discomfort, and further heightening fear and anxiety. Other techniques are also used to decrease a woman’s perception of pain such as distraction (a woman might be encouraged, for example, to focus on a special object from home or a photo) or massage by a supportive coach. Lamaze® courses are neutral regarding the use of drugs and routine medical interventions during labor and delivery and educate mothers about their options so informed decisions can be made. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic pain-management strategies provide women with specific techniques they can use to cope with the discomfort of labor, thereby increasing their feelings of control.

The Bradley Method® (also called “Husband-Coached Birth”) places an emphasis on a natural approach to birth and on the active participation and teamwork with the baby’s father as the birth coach. A major goal of this method is the avoidance of medications unless absolutely necessary. Other topics include the importance of good nutrition and exercise during pregnancy, relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing and concentration on body signals) as a method of coping with labor, and the empowerment of parents to

trust their instincts to become active, informed participants in the birth process. The course is traditionally offered in 12 sessions. Although Bradley® emphasizes a birth experience without pain medication, the classes do prepare parents for unexpected complications or situations, including emergency cesarean birth. After the birth, immediate breastfeeding and constant contact between parents and baby are stressed.

Hospital-based classes are offered in the third trimester and welcome the involvement of a birth companion during classes. The hospital-based prenatal class presents content seemingly biased to that particular institution and may focus primarily on the medical model. Usually a tour of the facility is included in the classes.

Carlton et al. (2005) question whether some hospital-based education serves to socialize women about the “appropriate” ways of giving birth rather than educating them.

There is a relationship between women’s expectation of labor and their actual experience of labor (

Green, 1993). Women who expect breathing and relaxation techniques to work are more likely to find them helpful. Women who wish to avoid medications can be successful with the help of educational preparation, their support system, and perinatal nurses who respect that plan. The labor admission assessment should include questions related to the type and amount of childbirth preparation (e.g., classes, reading, video tape viewing). As part of the admission assessment, the nurse should ask about the couple’s plans for pain management during labor and whether this subject was discussed with her obstetric provider. Asking about their plans and goals validates their efforts to prepare for labor and birth. Nurses should assure the woman and her support persons that the couple’s goals are understood and that achievement is a shared objective. Nurses have a responsibility whenever possible to facilitate an experience for each couple that matches their expectations (

Carlton, Callister, & Stoneman, 2005). Knowledge and skills learned in childbirth-preparation classes are enhanced when the nurse present during labor and birth believes in and actively supports the couple as they apply these principles.

HEALTHCARE ENVIRONMENT

Every perinatal unit takes a unique approach to caring for laboring women. A culture develops over time and is accepted by most of those working within the department as a reflection of their values and beliefs. Cultural differences may be as significant as the availability of labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum rooms (LDRPs) or as subtle as the routine initiation of intravenous fluids on admission. These practices reflect the evolution of intrapartum care within a particular institution. Unit culture extends to treatment of pain and influences the woman’s perception of pain. Nurses who value nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management use these techniques in clinical practice.

PAIN TOLERANCE

Pain is a culturally bound phenomenon. When a patient expresses pain, the form that expression takes is related to what her culture has taught her is appropriate. Pain tolerance may be defined as the level of stimuli at which the laboring woman asks to have the stimulation stopped. In labor, it is the point at which a woman requests pharmacologic pain relief or increased comfort measures. Descriptive words such as mild, moderate, and severe do not provide a measure of pain tolerance because laboring women may describe pain as severe but may not request pain medication. A woman’s pain tolerance or the length of time she is able to go without medication may be increased by the use of nonpharmacologic pain management techniques (

O’Sullivan, 2009).

The Joint Commission (

TJC; 2011), in 2001, established pain management standards for healthcare organizations, which require that patients (1) have appropriate assessment and management of pain, (2) are screened for pain during the initial assessment and reassessed periodically, and (3) are educated about pain management. Many hospitals use a rating scale to quantify the pain from 0 to 10, with a response of 4 or greater requiring intervention and 10 being excruciating pain. TJC does not mandate this particular rating scale but rather that their standards are followed.

Most hospitals have adapted one of the many available standardized pain assessment tools. Those used in adult populations, for the most part, require that the patient rate the intensity of pain she is experiencing. They are useful because there is some objectivity added to assessing and documenting phenomena that are very subjective. What these simplistic tools cannot tell the nurse is how the pain is being interpreted or translated by the woman in labor. What is her perception of the pain and how much is she suffering during labor? Only by being present and really listening, observing, and empathizing with a woman during labor can the nurse begin to understand what the experience of pain is for her and what interventions might be helpful to provide some relief (

King & McCool, 2004). There is still a need for research to find a suitable assessment instrument for the evaluation of labor pain (

Bergh, Stener-Victorin, Wallin, & Martensson, 2011).

Roberts et al. (2010) developed and implemented an alternative tool to the 0 to 10 rating scale, called The Coping with Labor Algorithm, which qualifies the woman’s ability and internal consciousness as coping or not coping with her labor. Signs of coping include rhythmic motion, breathing patterns, and stating she is coping. Noncoping cues include lack of concentration, crying, and stating she is no longer coping. Both

pathways incorporate nursing and supportive actions. The coping algorithm was found to be useful in the hospital setting and is being evaluated in other hospitals for ease of use and applicability. The Coping with Labor Algorithm has passed a Joint Commission survey.

Although pain may be quantified, it is only one component of a woman’s overall experience of labor and delivery. Personal satisfaction is not always correlated with the level of pain and should be included in the evaluation of pain (

Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Research has shown that alternative coping techniques may improve a women’s sense of control and satisfaction with childbirth (

Kimber, McNabb, McCourt, Haines, & Brocklehurst, 2008). Helping women cope with labor through methods to impact the affective component and decrease the sensory component may be viewed as ineffective by clinicians supportive of the pharmacologic model (

Lowe, 2002).