INTRODUCTION

Treating pain is a basic humanitarian concern (Park et al 2000). The desire to have one’s pain eased has a long tradition (Loeser 2005). Pain therefore must be a key responsibility for the nurse as a member of a multidisciplinary team and up-to-date knowledge of pain is essential throughout your nursing career. Pain is a problem in its own right, but may be associated with other areas of care. For example it has been suggested that between 30% and 70% of all surgical patients experience considerable postoperative pain and also that assessment of pain and pain relief is inadequately completed by both physicians and nurses (Klopfenstein et al 2000).

Pain is also a symptom common to many illnesses and therefore nursing knowledge in this field is vital. It has been found that nurses often lack knowledge and awareness of the resources available for the effective management of pain. Such nurses are therefore unable to perform their role effectively. Successful pain management can be difficult, requiring approaches that need multiprofessional teamwork. Pain can have harmful effects on many aspects of the body’s normal functioning and repair processes (Munafò & Trim 2000). Chronic changes within the nervous system can result from failure to control acute pain effectively; this can lead to neuropathic and chronic pain states (Woolf & Slater 2000). Chronic pain has many serious adverse effects and has been linked with suppressing immune function (McCaffery & Pasero 1999). This chapter will explore how pain might be experienced. Although most people can readily identify with the concept of physical pain, other areas such as the emotional, mental and psychological elements of pain are often overlooked.

This chapter is designed to further your knowledge and to encourage you to continue to explore this subject. The activities incorporated here are intended to act as a starting point for your development. It will help you explore the issues involved in the pain experience from a broad perspective. The approaches will encourage you to use other resources, including your personal and practical experience in various settings, library resources and interactions with your peers.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

This section considers the physiology of pain, pain transmission, physiological signs of pain, theories of pain, and psychosocial elements of pain.

Care delivery knowledge

This section considers the assessment of pain. Related symptoms relevant to pain assessment, the use of pain assessment tools, and the use of carers to aid assessment are also considered. Effective pain management, pharmacological interventions and modes of delivery, and non-pharmacological interventions are explored.

Professional and ethical knowledge

This section explores the nurse’s role in effective pain care in a plural society. The nurse’s specialist role and multidisciplinary team role in pain management are also examined. Ethical considerations around the delivery and management of pain are reviewed in the light of documents such as the Human Rights Act, 1998/2000 and Human Rights Act, 1998/2000 and the Children Act 1989/2004.

Personal and reflective knowledge

In this section you will bring together the issues covered by the previous three sections as well as your existing knowledge and experiences to explore the care of four individuals related to the specialist branches of nursing. It is also relevant to consider your personal gain in relation to your knowledge base and evidence of learning.

On pages 265–267 there are four case studies, each one relating to one of the branches of nursing. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

BIOLOGICAL

This section explores the physiology of pain. Theories of pain transmission are discussed and you are encouraged to apply these to your own experiences.

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN

It is necessary to consider several factors in relation to how pain is evoked and perceived. The relationships between the major components need to be understood and recognized. ‘Pain is a physiological and sensory process that is influenced by each person’s unique experience, culture and response’ (Cranford 2001: 288). In 1970, Merskey offered a definition of pain as ‘an unpleasant experience which we primarily associate with tissue damage or describe in terms of such damage or both.’ This definition allows for the concept of pain to be evoked even if there is no direct indication of tissue damage, and seems to agree with the everyday definition of pain. The exact mechanism for the transmission of pain is unknown, but several theories have been put forward. It is a recent phenomenon that there is acceptance that pain occurs on many levels and is specific to each person’s experience including genetics, current fears, past experience and their expectations of treatment (Jones 2001). It is important that you remember these are not facts but theories – a way that individuals can explore a concept.

Several theories of pain have evolved and guide the conceptualization of pain (Table 11.1).

| Theory | Theorist | Major contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Descartes (1664/1972) | Pain is a distinct sensation mediated by nerves designed for nociceptive processing with physiological specialization |

| Intensity | Erasmus Darwin (1794) | Pain is the result of intense stimulation of nerve fibres in any sensory organ |

| Pattern theories | Several conceptualizations of pain stimulus intensity and central summation are key concepts | |

| (a) Central | Livingstone (1943) | Central mechanisms for summating peripheral summation pain impulses and pathological stimulation of sensory nerves initiates activity in reverberating circuits between central and peripheral processes |

| (b) Sensory | Rapidly conducting fibre systems excite, and inhibit, synaptic transmission in the slowly conducting system for pain. From this evolved the theories of myelinated and unmyelinated fibre systems, functions of nerve fibres, and the multisynaptic afferent system | |

| Affect | Emotional quality of pain distorts all sensory events. Global theory accounting for the sensory, affective and cognitive dimensions of pain – pain processing not rigid, but flexible |

THE EVOLUTION OF PAIN THEORIES

Pain transmission

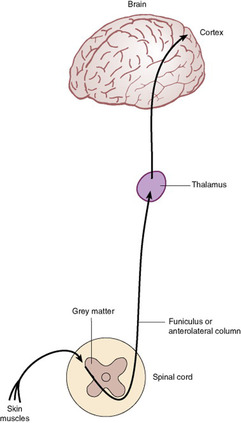

Pain fibres or nociceptors (noxious sensation receptors) are specialized neurones located throughout the body, particularly in the skin (Fig. 11.1). These specialized nerve endings recognize tissue damage. Pain results when the impulses from these nerves reach consciousness. The nerve endings can be stimulated by chemical, mechanical or thermal inputs. When the peripheral nerve fibres carrying impulses generated by the painful stimuli enter the spinal cord, they enter the dorsal horn of the spinal grey matter, passing through the dorsal root of the spinal nerve. When a nerve fibre ends it is involved in a synapse where the nerve message is chemically transmitted to the next nerve cell and its fibre. Many different chemicals are involved in transmission at different synapses and no one transmitter substance is confined to a single functional system. The primary actions and functions of some of these neurotransmitters are listed in Table 11.2. A useful introduction to pain perception/transmission can be found in Wood (2002).

• Try to describe in your own words how you as an individual are able to perceive pain.

• Given this description, reflect upon factors that would affect your perception of pain. It may be helpful here to compare the differing perceptions of pain when ‘banging your thumb’ or having a headache or having a toothache.

• Use this exercise to write a short summary for your portfolio, demonstrating your understanding of your own pain experience.

| Neurotransmitter | Action |

|---|---|

| Substance P | Is thought to be the neurotransmitter substance released that results in increasing pain perception |

| Enkephalins | Produce analgesia, euphoria and nausea |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine | Enhances pain transmission at local level, but inhibits pain when acting on central nervous system structures such as the dorsal horn |

| Beta endorphins | Probably responsible for dulling pain perception from injuries |

Gate theory

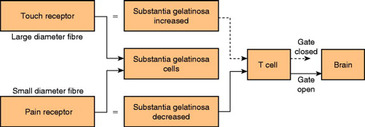

One of the most widely accepted theories of pain, first suggested in 1965, is the gate theory, which proposed that pain is determined by interactions between three spinal cord systems (Melzack & Wall 1996). Simply it suggests that the ‘transmission of pain from the periferal nerve through the spinal cord was subject to modulation by both intrinsic neurones and controls emanating from the brain’ (Dickenson 2002: 755). It proposes that pain impulses arrive at a gate, thought to be the substantia gelatinosa (one of the most dense neuronal areas of the central nervous system). When open the impulses easily pass through; if partially open only some pain impulses can pass through; and if closed none can pass through. It further suggests that the gate position depends on the degree of small or large fibre firing. Accordingly, when large fibre firing predominates (non-noxious sensations), the gate closes, and when small fibre firing predominates (pain fibres) the pain message is transmitted (Fig. 11.2). For more detailed information see Wood (2002). It is now evident that the actuality is more complex than this explanation. Dubner in 1997 found that the nervous system has the ability to change its sensitivity following tissue injury or nerve injury, termed plasticity. Gate theory also did not take into account the long-term changes that occur due to noxious stimuli or other external factors and also that there is not a single pain centre (Jones 2001).

• Consider in everyday life an experience where it may be possible to close the gate on pain (e.g. what might be your immediate reaction on ‘banging your thumb’?).

• Now consider where and when these mechanisms may be used in the practice of pain control in health care.

• Write a summary for inclusion in your portfolio.

|

| Figure 11.2 (adapted from Melzack & Wall 1965). |

PHYSIOLOGICAL SIGNS OF PAIN

In sudden acute pain certain physiological signs of pain may exist (Table 11.3); these are linked to the fight or flight mechanism of the adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) functions as an initial response to the experience of pain. However, over time the body seeks equilibrium physiologically as these responses cannot be maintained without causing physical harm. The major problem with physiological indicators of pain is that they may be due to other factors such as stress. Therefore although they may be indicators of acute and sudden pain, they are of little use as indicators of chronic pain. In chronic pain, lack of such signs may prompt the practitioner to inaccurately conclude that the patient does not look as if they are in pain (American Pain Society 1999) therefore they cannot be in pain.

| Physiological response to acute pain | Adaptation over time (chronic pain) |

|---|---|

| Increased blood pressure | Normal blood pressure |

| Increased pulse rate | Normal pulse rate |

| Increased respiration rate | Normal respiration rate |

| Dilated pupils | Normal pupil size |

| Perspiration | Dry skin |

Physiological manifestation of acute pain and adaptation

There are differences between acute and chronic pain and these impact upon the individual experiencing pain, since the physiological responses, psychological and social consequences differ. Acute pain is associated with a well-defined cause. There is an expectation that it is timebound and will disappear when healing has occurred. Chronic pain continues long after an injury has healed. It is a situation for the person experiencing it rather than an event (Munafò & Trim 2000).

Chronic pain can be further subdivided as either malignant or non-malignant. Chronic non-malignant pain is persistent and has no end point. It has far-reaching effects and may cause problems with partners, family, friends and employers. Loeser (2005) argued that chronic pain should be considered a disease in its own right. Treatment philosophies centre around helping patients to take responsibility for their pain and helping them to cope with it using a variety of strategies, such as in the care of a person with arthritis. Such strategies might include psychological interventions that focus on the behavioural, cognitive and emotional aspects of the illness, for example dealing with anxiety and depression, educating them about their condition and increasing the individual’s control by teaching coping skills. In contrast, chronic malignant pain may have an end point; treatment approaches include sufficient analgesia to relieve pain and techniques such as relaxation. Such differences in definition reflect the multidimensional nature of the pain.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has defined neuropathic pain as ‘pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system’ (Merskey & Bogduk 1994). However, this definition has more recently been criticized as being too vague. Because of the incidence of both malignant and non malignant diseases in an aging population and greater survival rates from cancer and its treatment, there is likely to be an increase in the occurrence of neuropathic pain (Dworkin 2002).

PSYCHOSOCIAL

PSYCHOSOCIAL ELEMENTS OF PAIN

In this section, definitions and ideologies are explored along with misconceptions of the experience of pain for the individual.

Pain is a difficult concept to understand. The assumption that there is a simple and direct relationship between a noxious stimulus and subsequent pain has been disputed by the realization that many environmental and internal factors modify pain perception (Main & Spanswick 2000). As has been previously stated, nociception is not pain until it is interpreted and perceived as pain. This pain perception is influenced by a range of factors. There are numerous causes of pain and these are not only physical. Also the terms ‘pain threshold’ and ‘pain tolerance’ (the greatest intensity of pain an individual can endure) are sometimes used synonymously. This leads to confusion since there are differences between them. There is also thought to be a link between a person’s pain threshold and their risk of developing chronic pain and this may be because they have a mixture of genetic mutations that increase their sensitivity to pain (Couzin 2006).

This is further complicated by factors such as emotion, culture and previous experience, the end result being a unique experience for that individual. It is important then, that the nurse working with a person experiencing pain is able to accept that pain is both physical and psychological. Thus pain is both biologically and phenomenologically embodied. Moreover culture intercedes in the pain experience and therefore transcends the mind–body divide.

Some of the recognized behavioural responses to both acute and chronic pain are listed in Table 11.4. These may be used as cues by nurses in their quest to determine the pain experience of the patient.

• In your own words try to define the term pain.

• Looking at this definition, explore how you view pain and from this try to consider on what your views are based. For example, you may have had a particularly painful experience that influences your views of pain or you may never have experienced pain.

• Consider whether these views affect your beliefs about other people in pain. If they do, in what way?

• Reflect on how your personal beliefs could affect your decision making when a patient or client requests pain relief.

| Behavioural response | Adaptation over time |

|---|---|

Observable signs of discomfort Focuses on pain Reports pain Cries and moans Rubs painful part Frowns and grimaces Increased muscle tension | Decrease in observable signs, though pain intensity unchanged Turns attention to things other than pain No report of pain unless questioned Quiet; sleeps or rests Physical inactivity or immobility Blank or normal facial expression |

BEHAVIOURAL RESPONSES TO ACUTE PAIN AND ADAPTATION

Pain has been defined as whatever the person experiencing it says it is, existing whenever the person says it does (McCaffery 1972). This definition allows for the complexity of pain, but in some ways limits its understanding. The literature indicates that the definition of pain depends upon the one person defining it. Wall’s (1977) definition ‘Pain is’ allows freedom for the practitioner to consider the individual phenomenon but could also be considered problematic due to individual attitudes and beliefs about pain. Knowledge of individual behaviours and changes that occur with discomfort are useful in distinguishing pain from other causes (Herr et al 2006); carers therefore become valuable allies in discovering the usual behaviours of the individual.

Pain causes powerful emotions in its sufferers: fear, anxiety, anger and depression are frequently cited. These emotions have a great impact on the individual’s understanding and control of the pain. Pain in any individual has to be judged by indirect evidence, and the appearance, non-verbal behaviour, physiological status and circumstance of the pain need to be interpreted (Fordham and Dunn, 1994 and Herr et al., 2006). Many misconceptions can be problematic in the interpretation of pain. The amount of tissue damage is not an exact prediction of the intensity of pain. It is easy to suppose that individuals receiving the same surgery will experience the same pain. The evidence is that the pain experience is individual and varies from both person to person and situation to situation. An individual’s reaction to pain is determined by past experiences, disposition, the cause of pain, their state of health and socialization, as well as factors such as the time of day and what else is going on around the person (Carr & Mann 2000).

In relation to behavioural responses to pain it is essential that vulnerable individuals, for whom behaviour may be a major characteristic, are considered. Vulnerable individuals would include young children and infants and people with impaired vocal or cognitive ability. A change in behaviour needs thorough evaluation of the likelihood of other sources of pain (Herr et al 2006).

In 2004, Van Hulle Vincent & Denyes investigated nursing knowledge and attitudes relating to relieving children’s pain. They found that the nurses in the study (n=67) had a moderately high ability to manage children’s pain. The more experienced paediatric nurses reported greater capacity to overcome barriers to the best possible pain relief. There was a positive correlation between pain score and analgesic given which suggests that nurses respond differently to higher pain scores.

Children may not have past experience of pain, but they learn quickly. Therefore an expression of distress in relation to tissue damage is of extreme importance to the infant’s survival. Pain would logically become one of the first emotions to emerge. It has been found that tolerance to pain increases with age, so the child is more likely to have an intense pain experience. In relation to the neural system of infants, it is now believed that the process of myelination occurs before birth and by birth myelination of the sensory roots has begun. Therefore the ability to experience and perceive pain has been established.

Many factors influence the way pain is perceived by the individual. Past experience of pain, the personality of the individual experiencing the pain, anxiety related to the pain experience and cultural influences all affect the pain sensation. Often there are obstacles in pain assessment because of faulty perceptions that cause nurses to doubt others who indicate they have pain (Cranford 2001). We need to be aware of this and by this awareness prevent ourselves from acting on these misconceptions.

Any past experience of pain or pain relief can affect the intensity of the pain (Carr and Mann, 2000 and Main and Spanswick, 2000). Pain can be influenced by the meaning it has to the individual. For example, the headache that you previously have dismissed as nothing may with a limited knowledge of medical theory be interpreted as being due to a brain tumour. This associated meaning will influence the way you perceive the pain. Anxiety, fear and depression can all increase pain sensation.

Watt-Watson et al (2001) found in their study of 94 nurses that they had deficits in knowledge and misbeliefs about pain management; also that their knowledge scores were not significantly related to their patients’ pain ratings. Patients reported moderate to severe pain but received only 47% of their prescribed analgesia.

PSYCHIATRIC/MENTAL PAIN

This complex issue has undergone considerable deliberation by many writers in recent years. The terms ‘hysterical pain’ and ‘operant pain’ have been used to describe the experience of patients who appear to be experiencing pain for psychological rather than physical reasons. It is important to consider that the patient’s expression of pain is as real to them, as it is to those who have pain due to an accepted cause such as surgery or fractured bones. Wall & Melzack (1999) write that they ‘have reservations of the use of this term in relation to its application to the theory of pain and psychological illness … Since those grouped under it include people whose pain is related to anxiety, depression and many psychiatric conditions’ (Wall & Melzack 1999: 931). They further state that it is important to distinguish these phenomena in order to apply appropriate treatment, whether antidepressants, psychotherapy or rehabilitative measures.

CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL INFLUENCES ON PAIN

The cultures within the profession of nursing or the institution of a hospital affect the way that pain is assessed, the way that decisions are made about the possible treatments, and the way that pain is managed.

Ethnicity in pain management is of particular significance in a multicultural country such as the UK. Each individual has intrinsic associations with culture: it socializes us to know what is expected of us and of others. Culture shapes beliefs and constrains behaviours. In such an environment the nurse must constantly be aware of professional issues in providing culturally appropriate care, and also of constraints on other practitioners due to their cultural beliefs and values. The process of the nurse–patient interaction occurs within the context of the demands and culture of the workplace (Walker et al 1995).

There are theological overtones in the pain experience as pain plays a central part in religious thought. The Christian concept is of pain as a paradox: Christ healed others in pain, but allowed himself to be crucified and endured agonizing pain. Pain is viewed as a challenge to be overcome. Buddha has been cited as a warrior, a saint and a victim. Examples of pain control can be found in many cultures, for example the Indian fakir who controls pain while lying on a bed of nails and the African tribes that practise lip or cheek piercing as ritualistic ceremonies do not appear to experience pain. Where stoicism is a cultural value, the behavioural expression of distress is generally less acceptable. Older people may view pain as a preliminary to death. Each culture has its own set of beliefs and attitudes with respect to the way people react to pain.

Care must be taken not to stereotype people, remembering that there is variability within cultures as well as between cultures. These misleading effects of cultural stereotypes, and the belief by nurses and doctors that they are the experts regarding the patient’s pain, lead to problems in assessing the patient’s pain. The under-treatment of pain, particularly among patients from racial and ethnic minorities, continues to be a problem in pain management (Green et al., 2003 and Burgess et al., 2006). Also the ethnicity of both the individual in pain and those attempting to assess the pain clouds the perceptions of health professionals (Walker et al., 1995 and Burgess et al., 2006). Professionals should consider the fact that the more difference there is between the patient and themselves the more difficult it is for them to assess and treat the patient.

Helman (2001) suggests that:

• Not all cultural or social groups respond to pain in the same way.

• Cultural background can influence how people perceive and respond to pain, both in themselves and others.

• Cultural factors can influence how and whether people reveal their pain to health professionals and others.

Gender is also an issue in the pain experience. Many of the debates around gender differences have focused on biological mechanisms, including genetic, hormonal and cardiovascular factors (Keogh & Herdenfeldt, 2002). Work by Kamp (2001) found that the men reported less severe pain than the women. Also that men’s and women’s pain experiences could relate to differences in their biology: the expectations and actions of healthcare professionals and society that treats the genders differently. Berkley (1998) found that females have lower thresholds of pain, greater abilities to discriminate pain, and higher pain ratings or less tolerance of noxious stimuli than males.

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

In order to make the most of decision-making skills in practice, the nurse must access appropriate knowledge to support and rationalize these actions. This section applies knowledge about the areas of pain assessment and relief of pain to the practice of nursing. You are encouraged to examine and apply this knowledge to exercises that will help you develop decision-making skills.

Nurses are the gatekeepers of medication usage and as such have a responsibility to increase their knowledge in pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological techniques for pain management. Nurses can be instrumental in pain management in all settings. The prescribing of analgesia by physicians on an ‘as required’ basis leaves the responsibility for the decision to give analgesia firmly with the nurse (Carr & Mann 2000). The recent changes in prescribing practices that allow nurses with appropriate education and training to prescribe some medications for their patients as nurse independent prescribers (NIPs) should have made a difference to this element of pain care where nurses can respond more proactively to the needs of their patients. See Evolve 11.1 presentation of NIPs.

The routine and traditional practices of many care institutions can pose difficulties in the assessment of pain. The use of ‘drug rounds’ may cause patients to comply, accepting analgesia at this time and feeling unable to ask for it at a more appropriate time for them. Skilful assessment techniques will limit this problem, identifying both the individual nature of the pain and its recurrence at more frequent intervals than the ‘drug round’ timing. An awareness of pain should therefore be a routine matter in caring for patients. Because of its subjective nature, the individual in pain is the only one who can assess the pain accurately (Cranford 2001).

Rituals in nursing practice can become entrenched, and in many healthcare institutions drugs are still administered via a ‘drug round’.

• During your practice placements compare the experiences of patients on the unit or ward that links pain relief to drug rounds and those where self-administration of drugs is the norm.

• To what extent do drug round practices need to be modified to suit individual needs for pain relief?

• How might ritualistic practices affect your decision making in relation to pain management?

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

Pain expression

Assessment is a process by which a conclusion is reached about the nature of a problem. Planning effective pain management is a crucial part of the nurse’s role. In order to achieve this it is necessary to assess the level of the individual’s discomfort in an attempt to identify a potential course of action. No single assessment strategy – e.g. interpretation of behaviours or estimates of pain by others – is sufficient by itself (Herr et al 2006). However, each element can be used in an endeavour to find a complete picture of the individual’s pain experience. The nurse needs to be able to draw conclusions about the individual’s pain to assess the level and intensity of the pain based on information from the patient. Once this has been achieved it is then possible to plan a course of action to alleviate the pain, implement this and evaluate the action. Although this is possible without the patient’s cooperation, it is better to involve the individual in the assessment of their pain. Otherwise nurses are simply applying their own beliefs and values to the situation and making assumptions about patients’ pain levels. Researchers suggest that the patient needs not only to be asked about their pain but also for their responses to be believed (Dahlman et al 1999). The nurse must be proactive and skilled in recognizing potentially painful situations, particularly in those instances where the patient may not be able to communicate verbally. To achieve this we need to ascertain whether pain assessment is an appropriate action, believe that the person has pain, and be committed to assessing the pain. This should lead to a clarification of the extent of pain and its treatment. In some circumstances this assessment will need to be not only accurate but also swift, for example when dealing with a patient suffering the pain of a myocardial infarction (heart attack), where the need for immediate and effective pain relief is a priority.

Although the nurse’s role in this area is paramount, the only individual who is truly able to assess the pain is the person who is suffering it. The patient’s spoken report of pain is the most reliable indication of pain (Cranford 2001). Wherever possible the patient should be assessing their pain rather than having it assessed by the nursing staff. In circumstances where the patient is unconscious, has a communication difficulty or is a baby, the nurse must make an informed decision based on the evidence presented by the patient, given that the family and other carers can be asked for further clarification.

Kim et al (2005) found that when assessing postoperative pain the nurses in their study relied on criteria related to the patient’s appearance and their past experience of the physical signs of pain rather than the report from the patient of their pain.

The accurate assessment of an individual’s pain is an inherently difficult process. The nurse must be able to establish a trusting relationship with the patient and his or her family or carers. The nurse must also be aware of their own beliefs and prejudices about pain. Timing of pain assessment is very important and dependent upon many factors, not least of which is the desire of the patient to participate in the assessment, the severity of the pain and the potential pain treatment. Such assessment involves the skills of observation so that the non-verbal pain behaviours can be seen and recognized (Box 11.1). It must be remembered that these behaviours are influenced by the individual’s social and cultural norms. Your interpretation will also be influenced by these factors. Therefore it is not possible to make assumptions based on the absence of a recognized non-verbal pain behaviour since each pain experience for the individual is unique.

Box 11.1

| Pain | Nature, intensity and site Likely cause Precipitating factors and circumstances (e.g. time of day, movement, eating) |

| Examples of non-verbal pain behaviours | Facial expression Change in mood Crying, screaming, wailing, weeping Lack of appetite Nausea, vomiting Pale or flushed skin colour Reluctance to move Increased activity Unusual behaviour Unusual posture Holding, pressing on the part that hurts |

| Related symptoms | Nausea, anxiety, breathlessness |

| Resources | Patient’s coping strategies Nursing knowledge and skills in using and teaching non-pharmacological methods of pain relief Medical and pharmacological knowledge and skills in both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods of pain relief Availability of resources such as time, equipment, privacy and so on |

| Meaning and significance to patient | Purpose and consequences |

The nurse may conclude that someone is in pain if they:

• state that this is the case

• demonstrate behaviour indicative of pain

• have undergone some experience that would be considered painful and they are unable to verbally report pain.

Mrs Singh is an elderly widow living in a maisonette. Her family live close by and have regular contact with her. She is receiving treatment for glaucoma and the community nurse has been asked by her general practitioner to assess her needs as her family are unable to instil her eye drops at lunchtime. She speaks very little English and has limited mobility. When the nurse arrives Mrs Singh is accompanied by her niece who says she has just arrived and is worried about her aunt who does not appear to be herself today. On meeting Mrs Singh she is sitting hunched in a chair and is moaning and rocking back and forth slightly.

• Consider the appropriate nursing actions in this instance.

• Using the list of aspects related to pain assessment in Box 11.1, decide what factors you would take into account in Mrs Singh’s case.

• Using a friend, role-playing Mrs Singh’s niece, complete an assessment of her pain.

• What more do you need to know that might help you in effective decision making about Mrs Singh’s care?

Related symptoms

An initial assessment should include some information about the history of the pain as follows:

1 Information about the initial onset of the pain. This includes a comparison of the medical history with the patient’s own version and allows similarities and discrepancies to be addressed. This may be linked to surgery, illness, trauma or an unknown cause. The patient may believe that something totally unrelated to the identified clinical cause of the pain is responsible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access