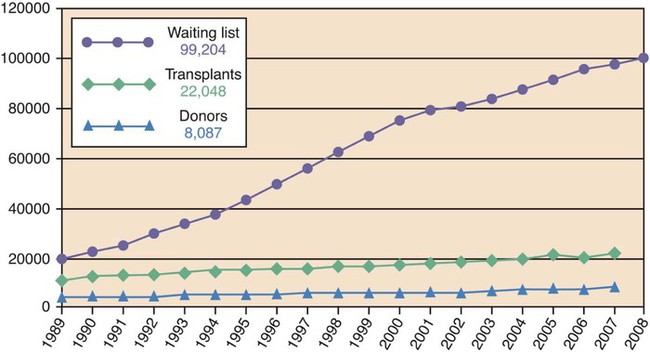

Jamie D. Blazek, Christine Hartley, Mary E. Lough, Mary Martel, Teresa J. Shafer and Schawnté Williams-Taylor Organ transplantation provides the only opportunity for patients with end-stage organ disease to have an enhanced quality of life and an extended survival. Organ transplantation is accepted as the preferred and often only treatment option for end-stage organ disease. Success rates in patients treated—as well as increases in organ donation from the general public—have improved as the field of organ donation and transplantation has evolved. Such evolution came as a result of increased cultural acceptance of brain death, donation, and transplantation; legal and political efforts to facilitate organ donation; improved procurement and allocation processes; advances in organ preservation, organ recovery, and surgical techniques in transplantation, immunology, immunosuppression; and management of infectious diseases.1 Nationwide, more than 114,241 people are waiting for a lifesaving or life-enhancing organ transplant. In 2011, the Organ Procurement Transplant Network (OPTN) reported 14,147 donors, of which 8128 were deceased donors and 6019 were living donors (Fig. 37-1). The categories of organ donors are described in Table 37-1. Total transplants performed in 2011 numbered 28,535. This is encouraging although insufficient, as one patient is added to a transplant waiting list every 10 minutes.2 TABLE 37-1 From United Network for Organ Sharing website. http://www.unos.org/donation. Accessed May 7, 2012. The critical care nurse is an essential member of the team in the donation process, linking the hospital to the organ procurement organization (OPO), physicians, and families of potential donors. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines, The Joint Commission standards, and hospital policies require that patients meeting criteria for imminent death and cardiac death be referred to an OPO in a timely manner.3 Once the notification has been made, nurses must follow the established donation policies for their hospital in accordance with federal guidelines and state laws. Hospitals will already have worked with their federally designated OPO to develop their hospital policy to ensure that it meets these regulations and laws. After death of the patient, nurses advocates for their patient by ensuring the patient’s donation decision is honored or—if the patient had not made such a decision during his or her lifetime—upholding the family’s right to be offered the opportunity to donate organs and tissues.4 Once authorization (formerly known as “consent”) is obtained, the OPO coordinator and nurse collaborate on management of the donor according to established donor management protocols. Such protocols include managing fluid and electrolyte imbalances secondary to brain death. It is not uncommon for patients to have a low circulating volume or high serum sodium levels, since hypertonic sodium may have been administered to prevent brain herniation. The donor management phase corrects deficits in the patient’s physiologic status in order to provide optimal organ function prior to surgical recovery and preservation. Nursing care shifts from cerebral protective strategies to aggressive donor management along with continued support of the family.5 A recent study of hospital donation practices and their impact on organ donation outcomes revealed gaps in knowledge of organ donation, brain death, referral criteria, and at times, a poor relationship between the hospital and OPO.6 It is important that nurses are knowledgeable about the organ donation process. Nurses must assess their own beliefs that pertain to organ donation since the attitude of the nurse and care given to the family can impact the outcome of the donation. Nurses, physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, social workers, and other health care disciplines practice in the hospital because that is where the patients are. OPO staff practice in hospitals because that is where the potential donors are. The 2003 Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative helped break down many of the silos that exist in providing care to patients by various health care professionals.7–9 Because only OPO staff or trained designated requestors can make the request for donation, they are part of the health care team. In one of the largest donor family studies in the nation, a primary finding was that speaking to an OPO staff member was one of the few variables highly associated with authorization (versus nonauthorization) for donation.10 A successful donation environment is dependent on a deep, close, and open relationship with a hospital’s designated OPO. The OPO should be called before the patient has died when death is imminent. This requirement is established by federal regulation, by state law, and is practiced by the vast majority of hospitals and critical care units as policy and best practice.3 Organ transplantation is the only medical and surgical therapy that is regulated entirely by law. From donation to transplantation, the federal government—and to some extent the state governments—monitor the administrative and financial aspects of this process. These regulations ensure that organs are shared on a fair and equitable basis. In addition, the responsibilities and functions of health care professionals are sanctioned and safeguarded by these laws so that their responsibilities may be discharged with assurance and protection medically, legally, and ethically. The major laws are listed in Table 37-2. TABLE 37-2 NATIONAL DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION LAWS From Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). http://www.organdonor.gov/legislation/timeline.html. Accessed May 7, 2012. The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) of 1968 established the legal framework for organ and tissue donation and donor designation, as well as the priority of legal next-of-kin for authorization in the absence of donor designation. It required that the physician pronouncing or certifying death may not in any way participate in the procedures for removing or transplanting anatomical gifts. It also protects health care professionals from liability associated with donation. The act was later amended to require hospitals to establish agreements with an OPO to coordinate recovery. It prohibits the sale or purchase of organs or tissues. This act clarifies who can provide authorization for donation in the absence of known donor wishes.11 This federal mandate required OPOs to coordinate the recovery and transplantation process at local levels and requires hospitals to be affiliated with a federally mandated OPO. There is only one designated OPO per service area. This act gave families the right to know about organ and tissue donation by mandating that all hospitals participating in the CMS reimbursement program institute a “required request” policy to ensure that families of potential donors are made aware of the option of organ or tissue donation and their option to decline. Hospitals must have a signed agreement with an OPO, tissue bank, and eye bank.3 Medical examiner laws encourage or require the release of organs for transplantation. In some states, medical examiners or justices of the peace cannot deny organ donation, under any circumstances. In other states, they cannot deny organ donation unless they are physically present at the donation surgery viewing the organ(s). In situations such as these, the medical examiner or justice of the peace may request a biopsy while in surgery. These state laws were passed to provide protection for recipients waiting at centers, so that every possible organ that can be recovered is being recovered to save a life (see Table 37-2). CMS requires hospitals to notify their respective OPOs of all deaths, including patients meeting imminent death criteria and cardiac death to increase the potential for organ, tissue, and eye donation. Table 37-3 lists the types of organ donor referrals made to the OPO. All patients meeting imminent death criteria must be referred within the agreed-upon time (usually within 1 hour) of meeting criteria. All cardiac deaths must be referred, irrespective of age, medical condition, or cause of death.3 The nurse or hospital designee makes the initial call to the OPO to provide demographic information, admitting diagnosis, and current neurologic status of the patient. Most OPOs have either in-house staff or on-call coordinators who will respond to the initial referral call from the hospital. Once onsite the OPO coordinator will communicate with the bedside nurse and physicians involved in the care of the patient to obtain information about the patient’s present hospital course, past medical history, and the plan of care. TABLE 37-3 ORGAN AND TISSUE DONOR REFERRALS TO THE ORGAN PROCUREMENT ORGANIZATION Developed by staff at LifeGift. Corporate headquarters Houston, TX. Determining medical suitability is solely the responsibility of the OPO. Speaking to the family about donation is also the responsibility of the OPO, unless designated requestors at the hospital have been trained to do so.3 Imminent death referrals include patients with severe acute brain injury who 1) require mechanical ventilation; 2) are in a critical care unit or emergency department; and 3) have clinical findings consistent with a low Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) typically 5 or less; patients for whom physicians are evaluating the diagnosis of brain death or have ordered that life-sustaining therapies be withdrawn, pursuant to the family’s decision.9 Once the initial call is made to the OPO an organ coordinator will contact the critical care nurse and request specific information regarding the patient’s age; sex; race; neurologic, ventilatory, and hemodynamic status; as well as the hospital’s plan of care. Once on site, the OPO coordinator will assess the patient and review the medical records, history of the current hospitalization, and major procedures—surgeries, therapies, current medications, past medical history, laboratory values specific to each organ, pulmonary status, systemic infection, diagnostic reports, and the hemodynamic status of the patient.12 The time between brain death declaration and organ procurement is often marked by significant instability. During this time, optimal medical management is crucial to ensure post-transplant graft survival. If the patient is not brain dead or there are no plans to withdraw support/decelerate care, the OPO coordinator will collaborate with the critical care nurse on a follow-up plan for ongoing evaluation. The OPO will continue to follow the patient until the patient meets neurologic criteria for brain death, death is declared, or there is a plan to withdraw life-sustaining support. Many patients referred to the OPO do not become donors because they do not meet brain death criteria or there are no plans to withdraw support as the patient’s status may improve. Patients declared dead by neurologic criteria constitute only 1% of total deaths in the United States.13 • Absence of severe hypothermia, defined as a core temperature of 32° C or less • Absence of hypotension, defined as a systolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or less • Absence of evidence of drug intoxication or poisoning, defined by a careful history, calculation of clearance, and if needed, a normal drug screen • Absence of recent or current administration of neuromuscular-blocking medications, defined by the presence of four twitches with maximal ulnar nerve stimulation by a train of four peripheral nerve stimulation as shown in Figure 21-17 in Chapter 21 • Absence of electrolyte, acid–base or endocrine dysfunction, as defined by severe acidosis and marked deviation from normal values Additional confirmatory testing for the determination of brain death may include cerebral angiography, electroencephalography, transcranial Doppler, and cerebral scintigraphy although these diagnostic procedures are not required (Box 37-1). The bedside clinical examination has three components: 1) absence of cerebral motor reflexes; 2) absence of brainstem reflexes; and 3) absence of respiratory drive. Pupillary signs are evaluated by absence of the light reflex, which is consistent with brain death. Most often the pupils are round, oval, or irregularly shaped, although dilated pupils may remain even after brain death has occurred. This dilation may exist if the sympathetic cervical pathways to the pupillary dilator muscle are intact. Medications do not normally alter pupil response, although the application of topical medications or severe trauma to the eye may affect pupil reactivity.14 Facial sensory and motor responses are elicited by testing for corneal and jaw reflexes. Stroking a cotton-tipped swab gently across the cornea tests the corneal reflexes. Grimacing in response to pain can be elicited by applying deep pressure to the nail beds, to the supraorbital ridge, or the temporomandibular joint. Severe trauma within these areas could inhibit interpretation of facial brainstem reflexes.14 Guidelines for determination of death recommend achieving Paco2 levels greater than 60 mm Hg for maximal stimulation of brainstem respiratory centers. Prerequisites and the procedure for apnea testing are outlined in Box 37-2. The prerequisites that should be addressed prior to the apnea test are to prevent cardiac dysrhythmias, hypotension, and decreased oxygen saturation. If any of these conditions occur during the apnea test, the test should be aborted and confirmatory testing should be performed (see Box 37-1). In cases where a patient is a CO2 retainer or the clinical examination is not reliable due to head trauma, confirmatory testing is necessary. Confirmatory testing is mandatory in children. As stated above, donation after cardiac death (DCD) is also known as donation after circulatory death determination (DCDD). DCDD is based on the cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions.15 Previously, DCD donors were known as non–heart-beating donors or asystolic donors. Patients who do not meet brain death criteria, but have an unsurvivable condition, such as a catastrophic neurologic injury, high spinal cord injury, or a medical condition requiring mechanical ventilation, are candidates for DCD. Before the enactment of brain death laws in the 1970s, all organ donors were DCD donors. Interest in DCD has increased due to 1) family interest in organ donation when neurologic criteria for brain death have not been met, and 2) the continued national demand for organs.16,17 DCD donors are classified as controlled and uncontrolled DCD donors. Controlled DCD occurs when the family has made a decision to withdraw life-sustaining support and death is declared at the time of circulatory arrest. In controlled DCD, families, health care providers, and OPO staff are involved in the timing and planning of the time when support will be withdrawn.14 Uncontrolled DCD describes a situation in which cardiac arrest has occurred and resuscitation efforts are determined to be futile. The uncontrolled DCD process is rapid as the patient is undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. After authorization from the family, the patient is taken to the operating room for immediate recovery of organs, primarily kidneys.18 DCD is an opportunity to increase the number of organs available for transplantation. Five-year organ survival rates in kidney and pancreas recipients from DCD donors and brain-dead donors are similar.19 Liver transplant grafts from DCD donors can encounter complications secondary to ischemic cholangiopathy (damage to the bile ducts from an impaired blood supply); consequently many transplant centers have changed their criteria for acceptance of DCD donors based on the age of the donor.20 DCD lung donor outcomes are favorable to those of brain-dead lung donors.21 The OPO coordinator is an advocate for the donor/donor family and potential recipients. Many factors are important in working with potential donor families. The nurse and OPO coordinator are important in providing a safe, comfortable environment for families in a position to make decisions about donation.22 Assessing the needs of the family is crucial to the outcome of the donation conversation. Timing of the conversation is also important. Donation does not consist of simply asking the family if they wish to donate.15 The critical care nurse should inform the family that an expert member of the health care team is available to provide information and answer their questions about donation.26 Many myths and misconceptions surround organ donation. Common misconceptions from families surround religious beliefs, cultural milieus, and concerns about possible body disfigurement, concern about the ability to have an open casket funeral, and costs to family.23 Another common misperception is that hospital staff will not attempt to save the life of their loved one if they believe the patient could be a donor.23 These misperceptions must be debunked with the family. Finally, research has shown the manner in which the donation request is made is the main factor in a family’s ultimate decision regardless of pre-existing attitudes.24 Many families report that donation has helped their healing in the grieving process and say that donation represents something positive in their loss.24 The donor management phase includes ongoing collaboration between the OPO coordinator and OPO medical director, critical care nurse, intensivist, respiratory therapist, and transplant professionals to ensure optimal preservation of organ function for organ recovery and transplantation.25 Standing orders for the care of an organ donor are provided by the OPO. These encompass required testing and screening of donors as well as parameters for continued medical management of the cadaveric donor, as listed in Box 37-3. The goals of donor management are to maximize oxygenation and provide optimal organ perfusion to maintain the viability of organs for transplantation as listed in Table 37-4.

Organ Donation and Transplantation

DONOR

DEFINITION

Brain-Dead Donor

Donor declared dead by neurologic criteria for brain death

Donation After Cardiac Death (DCD)

Donor declared dead by circulatory criteria for death

Living Related Donor

Living family member related by blood who donates a kidney, portion of the liver, pancreas, intestine, or lung to another family member

Living, Unrelated Donor (Directed/Nondirected)

Living individual not related to a patient requiring a transplant who donates a kidney, portion of the liver, pancreas, intestine or lung to another individual. The donor may be anonymous or altruistic

Organ Donation

Role of the Critical Care Nurse in Organ Donation

Organ Procurement Organization as Part of the Health Care Team

National Donation and Transplantation Laws

LAWS

TYPE

FIRST ENACTED

Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA)

State law

1968; Revised in 1987 and 2006

National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA)

Federal law

1984

Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA)

State laws

1980

Hospital Conditions of Participation—Organ Donation; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

Federal regulation

1998

Medical Examiner Laws Restricting Ability of Medical Examiner or Coroner to deny organ donation

State laws

Various years by state

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA)

Federal law

1986

The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act

Medical Examiner State Laws

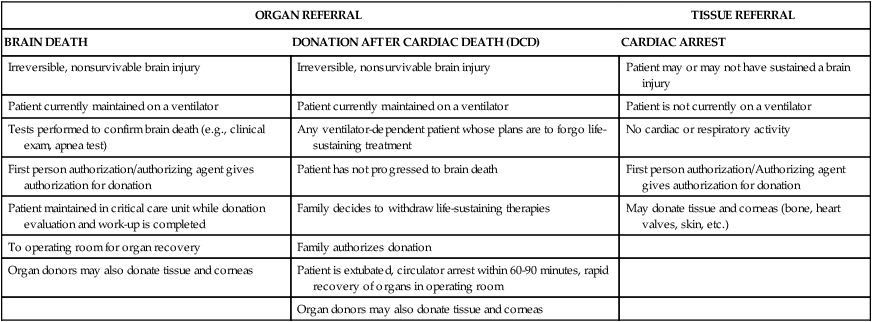

Overview of the Donation Process

ORGAN REFERRAL

TISSUE REFERRAL

BRAIN DEATH

DONATION AFTER CARDIAC DEATH (DCD)

CARDIAC ARREST

Irreversible, nonsurvivable brain injury

Irreversible, nonsurvivable brain injury

Patient may or may not have sustained a brain injury

Patient currently maintained on a ventilator

Patient currently maintained on a ventilator

Patient is not currently on a ventilator

Tests performed to confirm brain death (e.g., clinical exam, apnea test)

Any ventilator-dependent patient whose plans are to forgo life-sustaining treatment

No cardiac or respiratory activity

First person authorization/authorizing agent gives authorization for donation

Patient has not progressed to brain death

First person authorization/Authorizing agent gives authorization for donation

Patient maintained in critical care unit while donation evaluation and work-up is completed

Family decides to withdraw life-sustaining therapies

May donate tissue and corneas (bone, heart valves, skin, etc.)

To operating room for organ recovery

Family authorizes donation

Organ donors may also donate tissue and corneas

Patient is extubated, circulator arrest within 60-90 minutes, rapid recovery of organs in operating room

Organ donors may also donate tissue and corneas

Types of Referrals

Donor Evaluation

Brain Death

Confirmatory Tests

Brainstem Reflexes.

Pupillary Reflexes.

Corneal and Jaw Reflexes.

Apnea Testing.

Donation After Cardiac Death

Controlled Donation After Cardiac Death

Uncontrolled Donation After Cardiac Death

Authorization for Donation

Donor Management