27 Organ Donation and Transplantation

Introduction

Transplantation is a life-saving and cost-effective form of treatment that enhances the quality of life for many people with end-stage chronic diseases. Transplantation surgery commenced in Australia in 1911, with a pancreas transplant in Launceston General Hospital, Tasmania. Other tissue and solid organ transplantations followed, retrieved from donors without cardiac function; the first cornea in 1941; kidney in 1956; and livers and hearts in 1968. Transplantation in New Zealand began in the 1940s with corneal grafting, and the first organ transplants were kidney and heart valve transplantation in the 1960s.1

The first successful human-to-human transplant of any kind was a corneal transplant performed in Moravia (now the Czech Republic) in 1905.1 In September of 1968 an ad hoc committee of Harvard Medical School produced a report on the ‘hopelessly unconscious patient.’ The committee members agreed that life support could be withdrawn from patients diagnosed with ‘irreversible coma’ or ‘brain death’ (terms they used interchangeably) and that, with appropriate consent, the organs could be removed for transplantation.13 The committee’s primary concern was to provide an acceptable course of action to permit withdrawal of mechanical ventilatory support for the purpose of organ donation for human transplant. In 1981, a US President’s Commission declared that individual death depended on either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain. The consequent Uniform Determination of Death Act referred to ‘whole brain death’ as a requirement for the determination of brain death.13

Legislation that defined brain death and enabled beating-heart retrieval was enacted in New Zealand in 1964 and in Australia from 1982. This legislation heralded the establishment of formal transplant programs. In Australia, the first heart and lung program commenced in 1983, a liver transplant program in 1985, combined heart–lung transplant in 1986, combined kidney and pancreas in 1987, single lung in 19902,3 and small bowel in 2010. In New Zealand, bone was first transplanted in the early 1980s and the first heart transplant occurred in 1987. Skin transplantation occurred in 1991, lung transplantation in 1993, and liver and pancreas transplantation in 1998.4 The success of transplantation in the current era as a viable option for end-stage organ failure is primarily due to the discovery of the immunosuppression agent cyclosporin A.5

‘Opt-In’ System of Donation in Australia and New Zealand

There are currently two general systems of approach to seeking consent for cadaveric organ and tissue donation in operation around the world. Some countries (e.g. Spain, Singapore and Austria) have legislated an ‘opt out’, or presumed consent, system, where eligible persons are considered for organ retrieval at the time of their death if they have not previously indicated their explicit objection (see Table 27.1). In Australia, New Zealand, the US, the UK and most other common-law countries, the approach is to ‘opt in’, with specific consent required from the potential donor’s next of kin.6,7 In some states of Australia (for example, New South Wales and south Australia) and in New Zealand people indicate consent to organ donation on their driver’s licence or the Australian Organ Donor Register.8,9,10 In Singapore, the Human Organ Transplant Act of 1987 combines a presumed consent system with a required consent system for the Muslim population. The informed consent legislations of Japan and Korea are two of the most recent to come into force, in 1997 and 2000 respectively; before then, only living donation and donation after cardiac death were possible.11,12

TABLE 27.1 Type of legislation by country80–83

| Country | Type of legislation | Year and description of legislation |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Informed consent | 1982, donor registry since 2000 |

| Austria | Presumed consent | 1982, non-donor register since 1995 |

| Belgium | Presumed consent | 1986, combined register since 1987, families informed and can object to organ donation |

| Bulgaria | Presumed consent | 1996, in practice, consent from family required |

| Canada | Informed consent | 1980 |

| Croatia | Presumed consent | 2000, family consent always requested |

| Cyprus | Presumed consent | 1987 |

| Czech Republic | Presumed consent | 1984 |

| Denmark | Informed consent | 1990, combined register since 1990, previously presumed consent |

| Estonia | Presumed consent | no date identified |

| Finland | Presumed consent | 1985 |

| France | Presumed consent | 1976, non-donor register since 1990; families can override the wishes of the deceased |

| Germany | Informed consent | 1997 |

| Greece | Presumed consent | 1978 |

| Hungary | Presumed consent | 1972 |

| India | Informed consent | 1994 |

| Ireland | Informed consent | follows UK legislation |

| Israel | Presumed consent | 1953 |

| Italy | Presumed consent | 1967, combined register since 2000, families consulted before retrieval |

| Japan | Informed consent | 1997 |

| Latvia | Presumed consent | no date identified |

| Korea | Informed consent | 2000 |

| Lithuania | Informed consent | no date identified |

| Luxemburg | Presumed consent | 1982 |

| The Netherlands | Informed consent | 1996, combined register since 1998 |

| New Zealand | Informed consent | 1964 |

| Norway | Presumed consent | 1973, families consulted and can refuse |

| Poland | Presumed consent | 1990, non-donor register since 1996 |

| Portugal | Presumed consent | 1993, non-donor register since 1994 |

| Romania | Informed consent | 1998, combined register since 1996 |

| Singapore | Presumed consent | 1987, informed consent for Muslim population |

| Slovak Republic | Presumed consent | 1994 |

| Slovenia | Presumed consent | 1996 |

| Spain | Presumed consent | 1979, in practice, consent required from families |

| Sweden | Presumed consent | 1996, families can veto consent if wishes of the deceased are not known; previously informed consent |

| Switzerland | Informed consent | 1996, some Cantons have presumed consent laws |

| Turkey | Presumed consent | 1979, in practice, written consent required from family |

| United Kingdom | Informed consent | 1961, donor register since 1994 |

| United States | Informed consent | 1968, donor registers in some states |

Note: A combined register is a register of consent and refusal.

Types of Donor and Donation

Organ and tissue donation includes retrieval of organs and tissues both after death and from a living person. Donations from a living person include regenerative tissue (blood and bone marrow) and non-regenerative tissue (cord blood, kidneys, liver (lobe/s), lungs (lobe/s), femoral heads). The implications of consent are different for each type of requested tissue. For example, the collection of bone marrow, retrieval of a kidney, the lobe of a liver or lung are invasive procedures that could potentially risk the health and wellbeing of the donor.14 In contrast, donation of a femoral head could be the end-product of a total hip replacement, where the bone is otherwise discarded. Similarly, cord blood from the umbilical cord is discarded if not retrieved immediately after birth.

Organ Donation and Transplant Networks in Australasia

As part of the national reform package for the organ and tissue donation and transplantation sector, all state and territory health ministers agreed to the establishment of a national network of organ and tissue donation agencies, namely the Organ and Tissue Authority. This involved the employment of specialist hospital medical directors and senior nurses to manage the process of organ and tissue donation as dedicated specialist clinicians employed within the intensive care unit.1

The responsibility for leading this group of dedicated health professionals rests with the National Medical Director who supports this team through a Community of Practice (CoP) Program. This community of health professionals, along with the staff of the Authority, are the DonateLife Network, working together to share information, build on existing knowledge, develop expertise and solve problems in a collaborative and supported manner.1

The Organ and Tissue Authority

The Organ and Tissue Authority is the peak body that works with all jurisdictions and sectors to provide a nationally coordinated approach to organ and tissue donation for transplantation to maximise rates of donation. The role of the Authority is to ‘spearhead and be accountable for a new world’s best practice national approach and system to achieve a significant and lasting increase in the number of life-saving and life-transforming transplants for Australians’.1

The Authority was established in 2009 under the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority Act 2008 as an independent statutory authority within the Australian Government Health and Ageing portfolio. The DonateLife Network, under the Authority, include ‘DonateLife’ agencies and hospital-based staff across Australia dedicated to organ and tissue donation. DonateLife agencies were re-formed and re-named as a nationally integrated network to manage and deliver the organ donation process according to national protocols and systems and in collaboration with their hospital-based colleagues.1 Legislation in New Zealand is national, with Organ Donation New Zealand coordinating all organ and tissue retrieval from deceased donors.4

Regulation and Management

In Australia, quality processes involved in organ and tissue retrieval and transplant are governed by the Therapeutics Goods Administration.15 In New Zealand there is currently an unregulated market for medical devices and complementary medicines, although an agreement to establish a Joint Scheme for the Regulation of Therapeutic Products between the Governments of Australia and New Zealand is in place.15

The process of potential donor identification and management in critical care is directed by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS).13 Education of health professionals is facilitated by the Australasian Donor Awareness Program (ADAPT), in association with the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN) and the College of Intensive Care Medicine (CICM).

Donor criteria and organ allocation is regulated by the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ). Donor and recipient data are collated by the Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation Registry (ANZOD Registry). Professional groups related to this specialty area also cover both countries. The Australasian Transplant Coordinators Association (ATCA) is composed of clinicians working as donor and/or transplant coordinators, and the Transplant Nurses Association (TNA) is a specialty group for nurses working with transplant recipients (see Online resources).

Identification of Organ and Tissue Donors

The four main factors that directly influence the number of multi-organ donations are:

Brain Death

The incidence of brain death determines the size of the potential organ donor pool. Diagnosis of brain death is now widely accepted, and most developed countries have legislation governing the definition of death and the retrieval of organs for transplant.16 In Australia and New Zealand the most common cause of brain death has changed from traumatic head injury to cerebrovascular accident, which has implications for the organs and tissues retrieved as donors are older and often have cardiovascular and other co-morbidities.17 There is no legal requirement to confirm brain death if organs and tissues are not going to be retrieved for transplant.13

Two medical practitioners participate in determining brain death; in Australia one must be a designated specialist. Brain death is observed clinically only when the patient is supported with artificial ventilation, as the respiratory reflex lost due to cerebral ischaemia will result in respiratory and cardiac arrest. Artificial (mechanical) ventilation maintains oxygen supply to the natural pacemaker of the heart that functions independently of the central nervous system. Brain death results in hypotension due to loss of vasomotor control of the autonomic nervous system, loss of temperature regulation, reduction in hormone activity and loss of all cranial nerve reflexes. Table 27.2 lists the conditions commonly associated with brain death. Irrespective of the degree of external support, cardiac standstill will occur in a matter of hours to days once brain death has occurred.13,18

TABLE 27.2 Conditions associated with brain death65

| Condition | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Hypotension | 81% |

| Diabetes insipidus | 53% |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 28% |

| Arrhythmias | 27% |

| Cardiac arrest | 25% |

| Pulmonary oedema | 19% |

| Hypoxia | 11% |

| Acidosis | 11% |

Role of Designated Specialists

According to Australian law, senior medical staff eligible to certify brain death using brain death criteria must be appointed by the governing body of their health institution, have relevant and recent experience, and not be involved with transplant recipient selection. The most common medical specialties appointed to the role are intensivists, neurologists and neurosurgeons in metropolitan centres, and general surgeons or physicians in rural settings.17

In New Zealand the role is not appointed although medical staff confirming brain death must also act independently; neither can be members of the transplant team, and both must be appropriately qualified and suitably experienced in the care of such patients.13 The New Zealand Code of Practice for Transplantation19 also recommends that the medical staff not be involved in treating the recipient of the organ to be removed, and one of the doctors should be a specialist in charge of the clinical care of the patient.

Testing Methods

The aim of testing for brain death is to determine irreversible cessation of brain function. Testing does not demonstrate that every brain cell has died but that a point of irreversible ischaemic damage involving cessation of the vital functions of the brainstem has been reached. There are a number of steps in the process, the first being the observation period. An observation period of at least 4 hours from onset of observed no response is recommended before the first set of testing commences, in the context of a patient being mechanically ventilated with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of three, non-reacting pupils, absent cough and gag reflexes and no spontaneous respiratory effort.13 The second step is to consider the preconditions (see Box 27.1). Once the observation period has passed (during which the patient receives ongoing treatment) and the preconditions have been met, formal testing can occur.

Box 27.1

Preconditions of brain death testing13

Practice tip

When testing for corneal reflex, take care not to cause corneal abrasion, which might preclude the cornea from being transplanted if the patient is an eye donor. Invite the next of kin to observe the second set of clinical tests to assist their comprehension of brain death. Assign a support person to be with the family to assist in explaining and interpreting the testing process.84

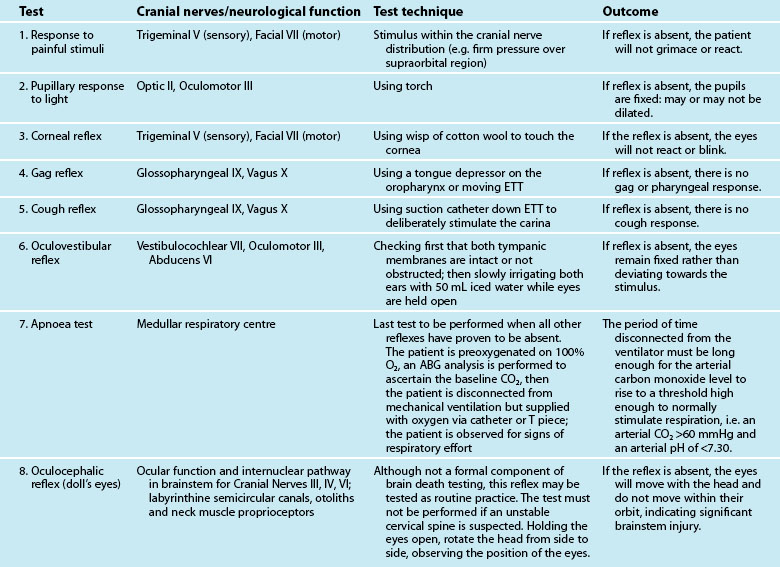

Formal testing for brain death is undertaken using either clinical assessment or cerebral blood flow studies.13 Clinical assessment of the brainstem, involving assessment of the cranial nerves and the respiratory centre (see Table 27.3) is the most common approach to testing. Brain death is confirmed if there is no reaction to stimulation of these reflexes, with the respiratory centre tested last and only if the other reflexes prove to be absent. If the patient demonstrates no response to the first set of tests, after a recommended observation period of at least 2 hours, the tests are repeated to demonstrate irreversibility.13

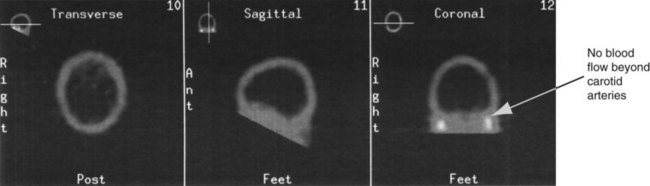

If the preconditions outlined in Box 27.1 cannot be verified, brain death can be confirmed using cerebral blood flow imaging to demonstrate absent blood flow to the brain, by either contrast angiography or radionuclide scanning. Contrast angiography can be performed by direct injection of contrast into both carotid arteries and one or both of the vertebral arteries, or via the vena cava or aortic arch. Brain death is confirmed when there is no blood flow above the carotid siphon13,20–22 (see Figure 27.1). A radionuclide scan is performed by administering a bolus of short-acting isotope intravenously or by nebuliser while imaging the head using a gamma camera for 15 minutes. No intracranial uptake of isotope confirms absent blood flow to the brain13,20–22 (see Figure 27.2).

If brain death is confirmed, the time of death is recorded as the time of certification of the testing result (i.e. at the completion of the second set of clinical tests, or the documentation of the results of the cerebral blood flow scan).13

Identification of a Potential Multiorgan Donor

The second factor influencing the number of actual organ donors is identification of a potential donor. A potential donor is defined in this situation as a patient who is suspected of, or is confirmed as, being brain dead. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for organ and tissue donation are constantly being reviewed and refined.23 Advice can be sought at any stage when considering the medical suitability of potential organ donors, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, from respective state and territory organ donation agencies (see Online resources).

Seeking Consent

The third factor influencing the number of donors is the consent-seeking process. Common practice in Australia and New Zealand is for the treating medical staff either to initiate or at least to be involved in approaching the next of kin after death has been confirmed.13,24 Approaching the next of kin to seek consent is part of the duty of care to patients who may have indicated their wish to be a donor at the time of their death.13,25,26 The act of offering the option of organ donation can also be considered part of the duty of care to the family.13 This view is supported by a survey of donor families, who indicated that they were grateful to have been provided with the option.27,28,31 Three elements are involved when approaching a family regarding the option of organ donation:

1. their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

2. their in-hospital experience29

3. any beliefs and biases of health professional/s conducting the approach.30

The outcome of an approach cannot be predicted or anticipated, as it may affect the ‘spirit’ in which the approach is made; a large US study demonstrated that clinical staff were incorrect 50% of the time when asked to predict the response of a next of kin.31

Influence of knowledge, beliefs and attitudes

Attitudes to organ donation are influenced by spiritual beliefs, cultural background, prior knowledge about organ donation, views on altruism and prior health experiences.32 Next of kin consider two aspects associated with existing attitudes and knowledge: the decision maker(s)’ own thoughts and feelings; and the previous wishes and beliefs of the person on whose behalf they are making the decision. There is evidence of a link between consent rates and prior knowledge of the positive outcomes of organ donation.33,34

Delivery of relevant information

An important consideration for all health professionals is that family members may have a diminished ability to receive and understand information because of their stress and psychological responses at this time of family crisis.35,36 As interviews held with the family are the foundation of the entire organ donation and transplant process,37 the discussion about brain death must be clear and emphatic, using language free of medical terminology, and include an explanation of the physical implications.38,39 Diagrams, analogies, scans and written materials have been suggested as useful aids for enhancing understanding by next of kin.25,40,41 One approach was to describe brain death as like a jigsaw puzzle with a piece missing, to illustrate the relationship of the brain to the rest of the body.41 Opportunities for staff to train and role-play this scenario with programs like ADAPT (see Online resources) improves the likelihood of meeting the needs of families.38,42–44

As the time of confirmation of brain death is the person’s legal time of death, a discussion is held with the family to discuss their options and associated implications. Options are to: (1) cease ventilation and allow cardiac standstill to occur; or (2) maintain ventilation and haemodynamic support to facilitate viable organ and tissue donation. The retrieval process must be fully explained to ensure an informed decision, but not to overload the next of kin.25,45 Table 27.4 lists some aspects of the organ donation process that could be included in such a discussion. As information given to a family contains both good news and bad news it is suggested to start with the good news – the benefits of donation, the right of the family to refuse consent, and the lack of cost; then move to the bad news – the reality of the surgical intervention and the lack of guarantee that the organs will be transplanted.45 Of note, a best practice approach aims to assist the family to make the decision that is ‘right’ for them and does not necessarily result in gaining consent.

TABLE 27.4 Information about the organ donation process and retrieval to assist in informed decision making85