Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Theory in Nursing Practice

Violeta Ann Berbiglia∗

Nurses work in life situations with others to bring about conditions that are beneficial to persons nursed. Nursing demands the exercise of both the speculative and practical intelligence of nurses. In nursing practice situations, nurses must have accurate information and be knowing about existent conditions and circumstances of patients and about emerging changes in them. This knowledge is the concrete base for nurses’ development of creative practical insights about what can be done to bring about beneficial relationships or conditions that do not presently exist. Asking and answering the questions “what is?” and “what can be?” are nurses’ points of departure in nursing practice situations.

History and Background

The Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory (SCDNT) is one of the nursing theories most commonly used in practice (Im & Chang, 2012). Orem’s dedication to the concept of self-care resulted in a nursing theory appropriate for present and future health care scenes. The earliest development of the theory occurred in 1956 (Orem, 1985). Orem’s purpose was to define the following:

• Nursing’s concern—“man’s need for self-care action and the pro-vision and management of it on a continuous basis in order to sustain life and health, recover from disease or injury, and cope with their effects” (Orem, 1959, p. 3)

• Nursing’s goal—“overcoming human limitations” (Orem, 1959, p. 4)

The concept of self-care evolved into a theory as Orem and colleagues discussed and formulated the concept into a working description of nursing. Orem’s model supports nursing through the following three central theories:

The significance of the utilization of Orem’s model in practice has been explicit since the publication of the first edition of Nursing: Concepts of Practice (Orem, 1971). Early use of the theory in practice began with the work of the Nursing Development Conference Group (NDCG) (1973). The group initiated their adventure into theory-based practice by integrating the developing concepts of the model into their clinical teaching. As the conceptualizations evolved, they were incorporated into nursing care.

Members of the NDCG were able to address the reality of theory-based nursing practice from their leadership positions that enabled control over nursing systems (Allison, 1973; Backscheider, 1971). Members of the NDCG valued their work in practice settings for supporting their conceptualizations and revealing the importance of the broad conceptualizations to structure practice. The Center for Experimentation and Development in Nursing at Johns Hopkins Hospital was one of the early sites for the development of the theory through practice. Later, in 1976, Allison implemented SCDNT-based practice in the Mississippi Methodist Hospital and Rehabilitation Center (Allison, 1989).

Gradually, SCDNT development in the practice arena began to filter into a variety of practice settings. In the 1980s the influence of the SCDNT on practice was accelerated. This was a time when the theory was being explicated for use with specific nursing situations and in varying types of practice settings. The literature of the 1990s shows SCDNT-guided practice in a variety of settings and situations. The emphasis was on prescriptions for specialized practice and model/theory development. Selected practice settings and conceptual foci are shown in Table 12-1.

TABLE 12-1

Utilization of Orem’s Model in Selected Practice Settings

| Author | Practice Setting | Conceptual Focus |

| Allison & McLaughlin-Renpenning, 1999 | Nursing administration | SCDNT |

| Armer, 2006 | Oncology | Self-care deficit, self-care agency |

| Bekel, 2002 | Variety of practice settings | Therapeutic self-care demand |

| Berbiglia & Bekel, 1995 | Variety of practice settings | SCDNT |

| Biggs, 2002 | Skilled nursing, elderly | Self-care |

| Biggs, 2008a | Home health care | Self-care limitations, self-care deficits, nursing systems |

| Biggs, 2008b | Variety of practice settings | SCDNT |

| Brooks & Armer, 2008 | Oncology | Power components, self-care |

| Dennis, 2002 | Normal newborn, postpartal mothers | Particularized self-care requisites, basic conditioning factors |

| Fleck, 2008 | Primary care | Support-educative nursing system, self-care |

| Flues, 2006 | Oncology | Self-care agency |

| Hanucharurnkul, 2004 | Diabetes self-management program | Self-care |

| Holoch, Gehrke, Knigge-Demal, et al., 1999 | Pediatric nursing | SCDNT |

| Horsburgh, 2002 | Home dialysis | Dependent-care agency |

| Howard & Berbiglia, 1997 | Korean women’s health care | Basic conditioning factors, developmental self-care requisites |

| Jesek-Hale, 2008 | Community prenatal clinic | Self-care |

| Kongsuwan, Kools, Sutharangsee, et al., 2008 | School | Self-care deficits, basic conditioning factors, self-care |

| Lorensen, 2000 | Rehabilitation, elderly | Self-care agency |

| Matchim, Armer, & Stewart, 2008 | Community | Self-care |

| Mohamed, 2006 | Outpatient clinic | Supportive-educative nursing system, self-care |

| Moore & Pawloski, 2006 | Community | Self-care |

| Norris, 1991 | Transplant outpatient service | Nursing systems |

| Orem, 2001 | Variety of practice settings | Nursing systems |

| Orem, 2004 | Variety of settings | Nursing practice science |

| Schmidt, 2006 | Variety of practice settings | Self-care in a supportive-educative nursing system |

| Taylor & McLaughlin, 1991 | Community | Self-care |

| Whitener, Cox, & Maglich, 1998 | Public school | Foundational capabilities |

With the founding of the International Orem Society for Scholarship and Nursing Science (IOS), an ongoing forum for the exchange of SCDNT practice models was established (Isenberg, 1993). The arrival of the twenty-first century brought with it the development of additional SCDNT practice models. Selected models of this period are displayed in Table 12-2.

TABLE 12-2

Selected SCDNT Practice Models for the Twenty-First Century

| Author | Model | Practice Setting |

| Allison & McLaughlin-Renpenning, 2000 | A framework for specifying nursing outcomes | Variety of areas of nursing practice |

| Biggs, 2008b | Putting a practice model into practice: Orem’s SCDNT | Variety of areas of nursing practice |

| Brooks, 2000 | Communication Model of Support | Variety of areas of nursing practice |

| Brooks, 2004 | Transtheoretical stages of change counseling framework | Nutrition management |

| Dennis, 2008 | Model for Dependent-Care | Dependent-care, self-care system of dependent-care agent |

| Fairchild, 2002 | Perioperative Nursing Practice Model (PNPM) | Variety of preoperative settings |

| Flues, 2008 | Practice Model for Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Case Management | Self-care systems, dependent-care systems |

| Grando, 2002 | Practice Model for a Comprehensive Nursing Rehab Program | Geriatrics nursing |

| Grando, 2005 | Psychiatric/Mental Health Advanced Practice Model | SCDNT |

| Hanucharurnkul, 2000 | Self-Care Agency Model | Oncology nursing |

| Hirunchunha, 2000 | Self-Care Model for Caregivers | Home health for stroke patients |

| Isaramalai, 2000 | Diabetes Self-Management Model | Diabetes management programs |

| Isaramalai, Rakkamon, & Nontapet, 2008a | Practice Model for Thai Industrial System | Estimative, transitive, and productive stages of care operations; self-care capability; helping methods |

| Isaramalai, Rakkamon, & Nontapet, 2008b | Practice Model for Thai Occupational Health Care System | Estimative, transitive, and productive stages of care operations; self-care capability; helping methods |

| Kolbe-Alberdi, 2004 | Model for Preoperative Nursing Rounds | Variety of preoperative settings |

| Maneewa, 2000 | Supportive and Educative Model in Promotion of Self-Care | Oncology nursing |

| Nantachaipan, 2000 | Self-Care Agency Model | HIV/AIDS |

| Phuphaibul, 2000 | Causal Model of Dependent-Care Burden in Parents | Chronic illness in children |

This review of the role the SCDNT plays in practice supports the theory’s versatility. A product of the post–World War II period, the theory continued into the new millennium as a guidepost for the profession. The timelessness of Orem’s theory, its practical approach, and the utility of the theory in decision making are essential to practice.

Overview of Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory

Nursing practice oriented by the SCDNT represents a caring approach that uses experiential and specialized knowledge (science) to design and produce nursing care (art). The body of knowledge that guides the art and science incorporates empirical and antecedent knowledge (Orem, 1995). Empirical knowledge is rooted in experience and addresses specific events and related conditions that have relevance for health and well-being. It is empirical knowledge that supports observations, interpretations of the meaning of those observations, and correlations of the meaning with potential courses of action. Antecedent knowledge includes previously mastered knowledge and identified fields of knowledge, conditions, and situations.

Orem (1995) identified eight fields of knowledge essential for understanding nursing practice. Seven of those emanate from previously developed fields of knowledge found in the sciences and other disciplines, including sociology, profession/occupation, jurisprudence, history, ethics, economics, and administration. The eighth, nursing science is knowledge about nursing practice created by nurses through scientific investigations that yield understanding of the field of nursing and provide foundations for nursing practice. In 2001, Orem characterized nursing science as composed of three nursing practice sciences and three foundational nursing sciences. The nursing practice sciences “define and explain three practice fields in nursing” (Orem, 2001, p. 175). The foundational nursing sciences “supply the foundations for understanding and for making required observations, judgments, and decisions in nursing practice situations” (Orem, 2001, p. 177).

Practice knowledge is systematized, validated, and conducive to dynamic processes. Its dynamic quality leads the user to acceptance and owning of the theory (Orem, 1988). Allison (1988) noted the dynamic quality of the SCDNT and commented that the theory always keeps the nurse in an action mode. Orem (1988) emphasized that today’s nurses must be scholars within the developing theory. In doing so, nurses are committed to an awareness of the relationship between what they know and what they do. From this awareness comes a healthy sense of professionalism.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Orem’s Theory

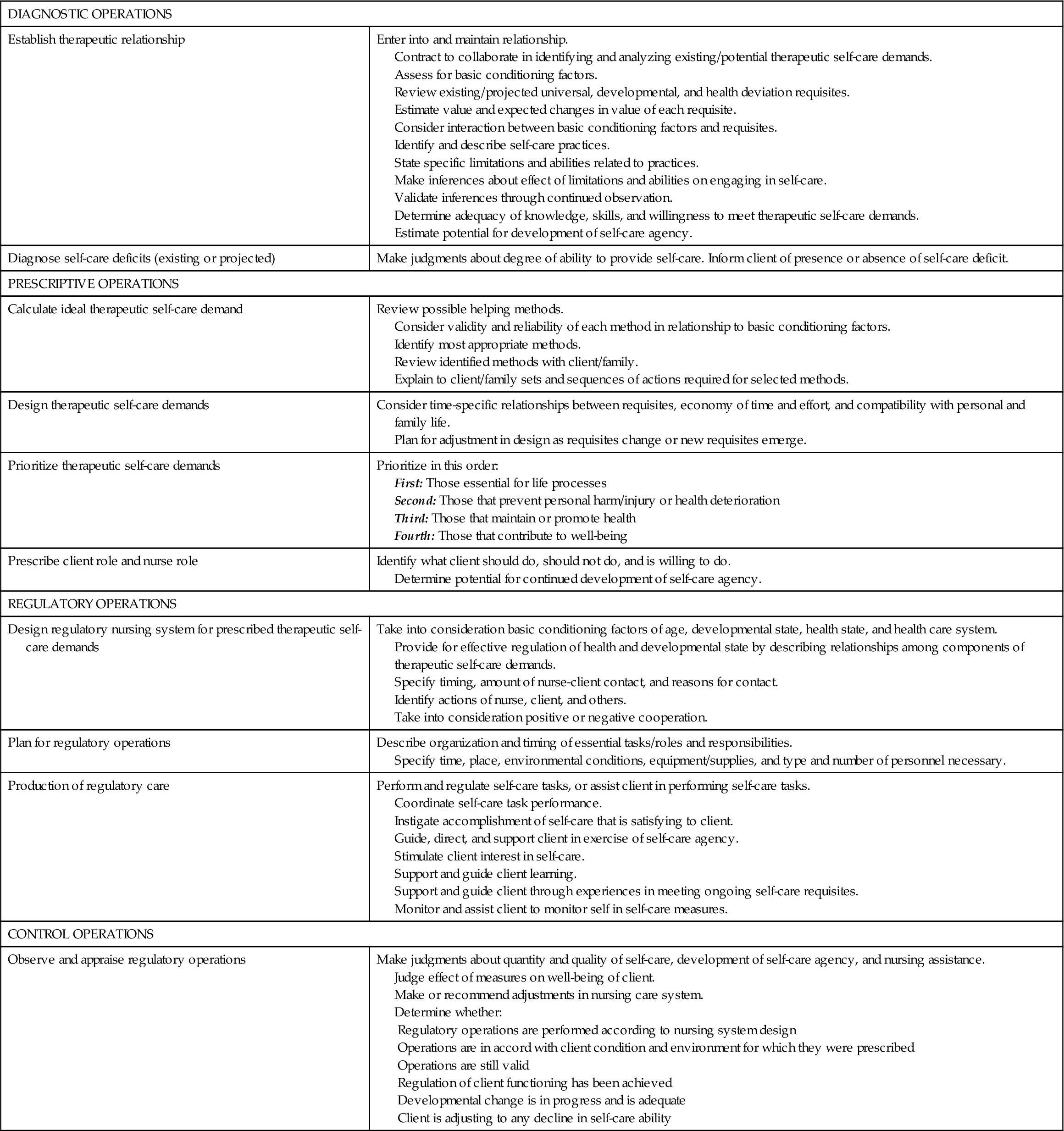

SCDNT-based critical thinking emanates from four structured cognitive operations: diagnostic, prescriptive, regulatory, and control. Each operation fulfills a distinct phase in the use of the theory. Sequencing of the phases may vary throughout the process in order to reassess and continue to prescribe and regulate the nursing system for the best interest of self-care.

The operations are intended to be collaborative and to provide the self-care agent or dependent-care agent input into the decision making. Examples of the four cognitive operations are found in this chapter’s discussion of the nursing care for two clients. Table 12-3 outlines the critical thinking requirements for SCDNT-based decision making. Critical thinking exercises are featured at the end of this chapter.

TABLE 12-3

| DIAGNOSTIC OPERATIONS | |

| Establish therapeutic relationship | Enter into and maintain relationship. Contract to collaborate in identifying and analyzing existing/potential therapeutic self-care demands. Assess for basic conditioning factors. Review existing/projected universal, developmental, and health deviation requisites. Estimate value and expected changes in value of each requisite. Consider interaction between basic conditioning factors and requisites. Identify and describe self-care practices. State specific limitations and abilities related to practices. Make inferences about effect of limitations and abilities on engaging in self-care. Validate inferences through continued observation. Determine adequacy of knowledge, skills, and willingness to meet therapeutic self-care demands. Estimate potential for development of self-care agency. |

| Diagnose self-care deficits (existing or projected) | Make judgments about degree of ability to provide self-care. Inform client of presence or absence of self-care deficit. |

| PRESCRIPTIVE OPERATIONS | |

| Calculate ideal therapeutic self-care demand | Review possible helping methods. Consider validity and reliability of each method in relationship to basic conditioning factors. Identify most appropriate methods. Review identified methods with client/family. Explain to client/family sets and sequences of actions required for selected methods. |

| Design therapeutic self-care demands | Consider time-specific relationships between requisites, economy of time and effort, and compatibility with personal and family life. Plan for adjustment in design as requisites change or new requisites emerge. |

| Prioritize therapeutic self-care demands | Prioritize in this order: First: Those essential for life processes Second: Those that prevent personal harm/injury or health deterioration Third: Those that maintain or promote health Fourth: Those that contribute to well-being |

| Prescribe client role and nurse role | Identify what client should do, should not do, and is willing to do. Determine potential for continued development of self-care agency. |

| REGULATORY OPERATIONS | |

| Design regulatory nursing system for prescribed therapeutic self-care demands | Take into consideration basic conditioning factors of age, developmental state, health state, and health care system. Provide for effective regulation of health and developmental state by describing relationships among components of therapeutic self-care demands. Specify timing, amount of nurse-client contact, and reasons for contact. Identify actions of nurse, client, and others. Take into consideration positive or negative cooperation. |

| Plan for regulatory operations | Describe organization and timing of essential tasks/roles and responsibilities. Specify time, place, environmental conditions, equipment/supplies, and type and number of personnel necessary. |

| Production of regulatory care | Perform and regulate self-care tasks, or assist client in performing self-care tasks. Coordinate self-care task performance. Instigate accomplishment of self-care that is satisfying to client. Guide, direct, and support client in exercise of self-care agency. Stimulate client interest in self-care. Support and guide client learning. Support and guide client through experiences in meeting ongoing self-care requisites. Monitor and assist client to monitor self in self-care measures. |

| CONTROL OPERATIONS | |

| Observe and appraise regulatory operations | Make judgments about quantity and quality of self-care, development of self-care agency, and nursing assistance. Judge effect of measures on well-being of client. Make or recommend adjustments in nursing care system. Determine whether: Regulatory operations are performed according to nursing system design Operations are in accord with client condition and environment for which they were prescribed Operations are still valid Regulation of client functioning has been achieved Developmental change is in progress and is adequate Client is adjusting to any decline in self-care ability |

Diagnostic Operations

The first phase, diagnostic operations (see Table 12-3), begins with establishing the nurse-client relationship and proceeds to contracting to work toward identifying and discussing current and potential therapeutic self-care demands. Basic conditioning factors are noted and considered in relationship to a thorough review of universal, developmental, and health deviation self-care requisites and related self-care actions. The projected value of requisites is estimated. An analysis of the assessment data results in a diagnosis concerning the type of self-care demands. Self-care agency is addressed through an assessment of self-care practices and the effects of related limitations and abilities. Personal characteristics such as intellect, skill performance, and willingness are evaluated. From these data, inferences about the adequacy and potential of self-care agency are made, validated, and treated as diagnostic of self-care agency. Finally, self-care deficits are diagnosed by reflecting on the adequacy of agency to meet specific requisites. In instances in which self-care agency is inadequate, a self-care deficit is stated.

Prescriptive Operations

In the prescriptive phase, ideal therapeutic self-care requisites for each self-care requisite are determined by reviewing possible helping methods, considering related basic conditioning factors, and identifying the most appropriate helping methods. Actions required for the therapeutic self-care demands are discussed with the client and are designed for maximal efficiency and compatibility. Priority is given to those therapeutic self-care demands that are the most essential to physiological processes. Client and nurse expectations are formalized and recognized as supportive of continued development of self-care agency.

Regulatory Operations

The prescriptions that evolve are used in the regulatory phase to design, plan, and produce the regulatory nursing system. Factors entering decisions about design include basic conditioning factors, effective regulation of health and developmental state, timing, assignment of actions, and degree of cooperation. Further planning specifies conditions for the regulatory operations such as frequency, equipment and supplies, and personnel needed. Throughout the production of regulatory care, there is emphasis on development of self-care agency by using helping methods that encourage learning, increase feelings of well-being, and stimulate interest in self-care.

Control Operations

Evaluation occurs in the control phase. The effectiveness of regulatory operations and client outcome is estimated. Regulatory operations are evaluated for correctness and appropriateness. Client outcome is appraised for regulation of functioning, developmental change, and adjustments to varying levels of self-care ability.