Chapter 15 Oral complications of HIV infection

Introduction

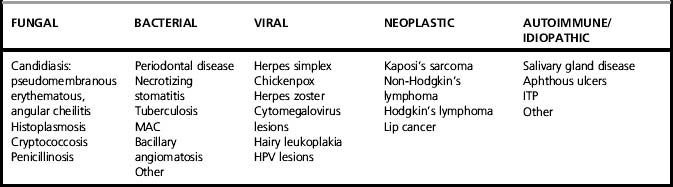

Oral lesions have been recognized as prominent features of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection since the beginning of the epidemic, and continue to be important [1, 2]. Some of these changes are reflections of reduced immune function manifested as oral opportunistic conditions, which are often the earliest clinical features of HIV infection. Some, in the presence of known HIV infection, are highly predictive of the ultimate development of the full syndrome, whereas others represent the oral features of AIDS itself. The particular susceptibility of the mouth to HIV disease is a reflection of a wider phenomenon. Oral opportunistic infections occur in a variety of conditions in which the teeming and varied micro-flora of the mouth take advantage of local and systemic immunologic and metabolic imbalances. They include oral infections in patients with primary immunodeficiency, leukemia, and diabetes, and those resulting from radiation therapy, cancer chemotherapy, and bone marrow suppression. Oral lesions seen in association with HIV infection are classified in Table 15.1, and our general approach to the diagnosis and management of oral HIV disease is summarized in Table 15.2. Standardized definitions and diagnostic criteria for these lesions have been established and recently revised [3, 4].

Table 15.2 Diagnosis and management of oral HIV disease

| Condition | Diagnosis | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Fungal | ||

| Candidiasis | Clinical appearance KOH preparation Culture | Antifungals Treatment for 2 weeks with systemic or topical agents Topical creams for angular cheilitis |

| Histoplasmosis | Biopsy | Systemic therapy |

| Geotrichosis | KOH preparation Culture | Polyene antifungals |

| Cryptococcosis | Culture Biopsy | Systemic therapy |

| Aspergillosis | Culture Biopsy | Systemic therapy |

| Bacterial | ||

| Linear gingival erythema | Clinical appearance | Plaque removal, chlorhexidine |

| Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis | Clinical appearance | Plaque removal, debridement, povidone-iodine, metronidazole, chlorhexidine |

| Necrotizing stomatitis | Clinical appearance Culture and biopsy (to exclude other causes) | Debridement, povidone-iodine, metronidazole, chlorhexidine |

| Mycobacterium avium complex | Culture Biopsy | Systemic therapy |

| Klebsiella stomatitis | Culture | Systemic therapy (based on antibiotic sensitivity testing) |

| Viral | ||

| Herpes simplex | Clinical appearance Immunofluorescence on smears | Most cases are self-limiting Oral acyclovir or valacyclovir |

| Herpes zoster | Clinical appearance | Oral or intravenous acyclovir |

| Cytomegalovirus ulcers | Biopsy, immunohistochemistry for CMV | Ganciclovir |

| Hairy leukoplakia | Clinical appearance Biopsy; in situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus | Not routinely treated Oral acyclovir or valacyclovir for severe cases |

| Warts | Clinical appearance Biopsy | Excision |

| Neoplastic | ||

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Clinical appearance | Palliative surgical or laser excision for some bulky or unsightly lesions; intralesional chemotherapy or sclerosing agents; radiation therapy; chemotherapy |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Biopsy | Chemotherapy |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Biopsy | Excision or radiation therapy or both |

| Other | ||

| Recurrent aphthous ulcers | History Clinical appearance Biopsy (to exclude other causes) | Topical steroids, such as fluocinonide mixed 50/50 with orabase, applied to lesions 4 times a day Thalidomide for most severe cases |

| Immune thrombocytopenic purpura | Clinical appearance Hematological work-up | |

| Salivary gland disease | History Clinical appearance, Salivary flow measurements Biopsy (to exclude other causes); needle or labial salivary gland biopsy) | Salivary stimulants or change in systemic medication or both Consider use of Salagen or Evoxac Topical fluorides, toothpastes and rinses |

In the prospective cohorts of HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men in San Francisco, hairy leukoplakia was the most common oral lesion (20.4%), and pseudomembranous candidiasis the next most common (5.8%) [5]. The relationships between prevalence of oral lesions and CD4 count or HIV viral load shows fairly close correlations [6–10]. These lesions occur at an early stage after seroconversion and are predictors of progression [11]. Oral lesions are also common in HIV-infected women [9–13] and children [14, 15]. While their overall frequency has fallen with the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), in both resource-rich and resource-poor countries among those who are treated for HIV infection, changes in their nature and relative frequency have been seen, with major decreases in Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma, oral candidiasis, and hairy leukoplakia, no changes in aphthous ulcers, and often increases in oral papillomavirus warts [16–18]. Some of the post-ART increases may represent oral aspects of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [19]. However, oral lesions are more common in people who smoke cigarettes [20].

Candidiasis (Oral Candidosis)

The pseudomembranous form of oral candidiasis/candidosis (thrush) was described in the first group of AIDS patients and is a harbinger of the full-blown syndrome in HIV-infected individuals [21, 22]. We have shown that both oral candidiasis and hairy leukoplakia predict the development of AIDS in HIV-infected patients independently of CD4 counts [23]. However, it is not well recognized that oral candidiasis can take several forms, some of them with subtle clinical appearances [24]. The most common form, pseudomembranous candidiasis, appears as removable white plaques on any oral mucosal surface (Fig. 15.1). These plaques may be as small as 1–2 mm or may be extensive and widespread. They can be wiped off, leaving an erythematous or even bleeding mucosal surface.

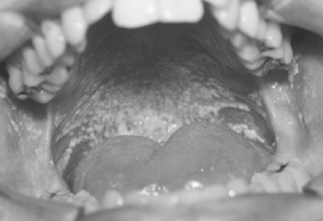

The erythematous form (Fig. 15.2) is seen as smooth red patches on the hard or soft palate, buccal mucosa, or dorsal surface of the tongue. These lesions may seem insignificant and may be missed unless a thorough oral mucosal examination is performed in good light.

Angular cheilitis (Fig. 15.3), due to Candida infection, presents as erythema, cracks, and fissures at the corner of the mouth. We have found that erythematous candidiasis is as serious a prognostic indicator of the development of AIDS as pseudomembranous candidiasis [24].

Diagnosis of oral candidiasis involves potassium hydroxide preparation of a smear from the lesion (Fig. 15.4). Culture provides information about the species involved. However, because a positive candidal culture can be obtained from over 50% of the normal population, culture is usually not useful for diagnosis. It may be helpful in cases of oral candidiasis unresponsive to antifungal therapy to determine Candida spp. and/or possible azole-resistant candidiasis.

Treatment

Oral candidiasis in patients with HIV infection can be treated with oral or systemic therapy and sometimes a combination of both [25]. Our approach is as follows.

Fluconazole (Diflucan) is a systemic antifungal agent. The recommended dose is a 100-mg tablet, once daily for 14 days. Oral fluconazole is an effective antifungal agent that does not depend on gastric pH for absorption. Side effects include nausea and skin rash. Two 100-mg tablets are used on the first day, followed by one 100-mg tablet daily until the lesions disappear. Fluconazole is also available as an oral suspension, 10 mg/mL, and 10 mL used as a swish and swallow once per day [26]. Itraconazole is a systemic, triazole antifungal agent and is available as a capsule and suspension. Itraconazole oral solution has been evaluated in clinical trials as being an effective agent in the treatment of oral candidiasis, and salivary levels of itraconazole persist up to 8 h after dosing. Itraconazole capsules are now available as 100-mg caps, 2 to be taken once or twice/day for 2 weeks. This may be useful in cases that do not respond to fluconazole or clotrimazole. Antifungal therapy should be maintained for 2 weeks, and some patients may need maintenance therapy because of frequent relapse.

In the years before ART was widely used, many cases of oral candidiasis resistant to fluconazole were reported. Such complications are now rarely seen in countries where ART is widely available. Factors associated with the development of resistance include CD4 count < 100 cells/mm3, previous use of fluconazole, and the emergence of new resistant strains of Candida albicans or the emergence of strains such as Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, and Candida krusei, which are inherently less sensitive to fluconazole [27]. However, in most cases, fluconazole is an extremely well-tolerated and effective antifungal agent.

Occasionally, other and unusual oral fungal lesions have been seen. They include histoplasmosis [28], geotrichosis [29], aspergillosis [30], Penicillium marneffei lesions, and cryptococcosis [31].

Gingivitis and Periodontitis

Unusual forms of gingivitis and periodontal disease [32] are seen in association with HIV infection, notably in groups where ART is not available such as in many geographic areas with high HIV prevalences. The gingivae may show a fiery red marginal line, known as linear gingival erythema, even in mouths showing absence of significant accumulations of plaque [33]. In early reports in the USA and Europe, the periodontal disease necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis occurred in approximately 30–50% of AIDS clinic patients [34] but was rarely seen in asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals [35]. It resembles, in some respects, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) superimposed on rapidly progressive periodontitis (Fig. 15.5) and is frequently seen in African AIDS patients. Thus, there may be halitosis and a history of rapid onset. There is necrosis of the tips of interdental papillae, with the formation of cratered ulcers. However, in contrast to patients with ANUG, these patients complain of spontaneous bleeding and severe, deep-seated pain that is not readily relieved by analgesics. There may be rapid progressive loss of gingival and periodontal soft tissues and extraordinarily rapid destruction of supporting bone. Teeth may, therefore, loosen and even exfoliate. The periodontal disease often demonstrates alarming severity and a rapid rate of progression not seen by the majority of practicing dentists and periodontists prior to the AIDS epidemic. Exposure and even sequestration of bone may occur, producing necrotizing stomatitis lesions [36] similar to the noma seen in severely malnourished people in the Second World War, and more recently in developing countries in association with malnutrition and chronic infection, such as malaria. The pathologic and microbiologic features of these remarkable periodontal lesions are well documented [37]. Standard therapy for gingivitis and periodontitis is ineffectual. Instead, the therapeutic regimen that is effective [38] involves thorough debridement and curettage, followed by application of a combination of topical antiseptics, notably povidone-iodine (Betadine) irrigation followed with chlorhexidine (Peridex or PerioGard) mouthwashes, sometimes supplemented with a 4- to 5-day course of antibiotics, such as metronidazole (Flagyl) 250 mg q.i.d., Augmentin 250 mg (1 tab t.i.d.), or clindamycin 300 mg t.i.d. Treatment will fail if thorough local removal of bacteria and diseased hard and soft tissue is not achieved during the initial treatment phase and maintained long term. Our impression has been that the diagnosis and management of the periodontal complications of HIV/AIDS are challenging and are less likely to be successful unless carried out by, or under the supervision of, experienced dental health professionals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree