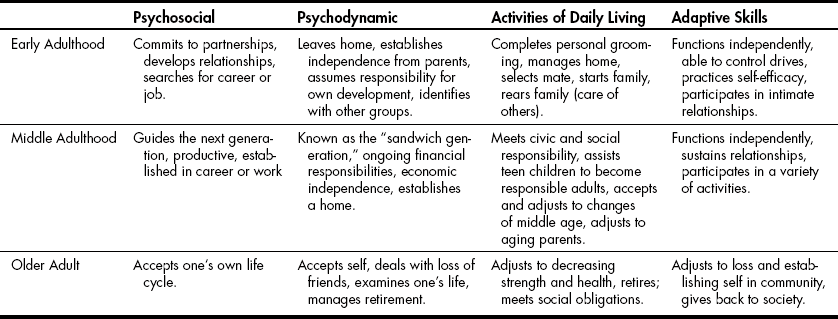

Chapter 10 Developmental Tasks of Adulthood General Conditions and Populations Occupational Strengths and Weaknesses Client Factors and Body Functions Sample Teaching and Learning Activity Task Analysis: Analyzing Occupational Performance∗ Role Playing as a Tool to Practice Group Leadership Skills Reflection and Self-Evaluation 1 Describe the developmental tasks of adults. 2 Use the occupational therapy practice framework to analyze activities. 3 Develop group sessions for adults. 4 Develop skills to complete an occupational and task analysis for adult group sessions. Occupational therapy (OT) practitioners often work with adults in groups for a wide variety of purposes. Compared with individualized sessions, the group format promotes social participation and encourages self-directed active participation. Members support and serve as role models for each other. This process allows clients to engage in the therapeutic process to reach their individual goals. Groups also provide an opportunity for the practitioner to observe the individual’s skills in action (Figure 10-1). This chapter begins with a description of the developmental tasks of adulthood, followed by an overview of how to design groups for adults who have a variety of physical or psychosocial conditions. Using the occupational therapy practice framework (OTPF)1 as a guide, the chapter provides examples of how to analyze areas of performance, occupations, client factors, and tasks. It describes the group process and outlines teaching techniques to help readers understand the group process when working with adults. Adulthood is generally considered to comprise the ages of 21 to 65 years; clients who are older than 65 years are most commonly referred to as being in late adulthood (see Chapter 11). See Table 10-1 for an overview of the developmental tasks of adulthood. The developmental tasks of early adulthood include finding one’s work, establishing intimacy, and living independently. The tasks of middle adulthood involve establishing one’s family, being productive in work, and caring for self and others. At this stage, many adults may be raising children and taking care of their own parents, explaining why this stage is often referred to as the “sandwich generation.” A recent phenomenon reports that many middle adults have young adult children returning home. Late adulthood includes such tasks as contributing to society, reestablishing one’s goals, and concern over one’s legacy. At this time, adults are productive workers who may be decreasing work time as they near retirement age and considering options. As they age, adults become aware of declining physical performance. TABLE 10-1 Developmental Tasks of Adulthood Adapted from Llorens L: Application of developmental theory for health and rehabilitation, Rockville, MD, 1976, American Occupational Therapy Association. Understanding the developmental tasks of adulthood can help practitioners develop appropriate intervention plans. Practitioners realize that all adults progress through the stages differently and at different rates.3 OT practitioners work with adults who have experienced a disruption in occupational performance caused by illness, disease, or trauma related to physical or psychosocial conditions.3 Notably, the onset of many psychosocial conditions occurs in early adulthood reguiring occupational therapy intervention. Practitioners may also work with young adults who have sustained a head trauma, spinal cord injury, or physical trauma resulting from high-risk activity (which are prevalent at this age). Additionally, Adults with chronic conditions may require the services of an OT practitioner. OT practitioners begin designing groups for specific populations by first reviewing individual goals and objectives. This includes understanding the present functional levels and necessary accommodations of all members. Identifying group members based on individual needs and the goals of the group is necessary before designing the group. Once the group goals are identified, the practitioner schedules the group, implements the session, documents outcomes, and evaluates the session. The steps of group design help practitioners develop the necessary skills to lead effective group intervention (Box 10-1). Conducting an occupational profile to explore the client’s past history, goals, desires, environment, strengths, and weaknesses provides the practitioner with the foundation for intervention planning. Understanding the client’s values, interests, motivations, and beliefs about their abilities and competence, which Kielhofner2 terms volition, is central to designing occupation-based intervention activities. Determining the client’s physical, cognitive, and psychosocial strengths and weaknesses allows the practitioner to develop a whole picture of the client needed to develop goals and objectives (see Chapters 6 and 7). OT practitioners develop goals and objectives that are meaningful to the client and address an area of occupational performance. Goals are designed to address areas of occupation. Areas of occupation include activities of daily living (ADLs; feeding, dressing, bathing, toileting, grooming), instrumental ADLs (IADLs), work, leisure and play, sleep, community mobility, and education.1 These areas form the domain of OT. Groups may be focused on specific areas of occupation. See Table 10-2 for sample groups addressing specific areas of occupation. TABLE 10-2 Sample Groups Based on Selected Areas of Occupation OT practitioners carefully analyze activity to best understand how to modify or adapt tasks for individual clients. Many sample formats exist to analyze activity. The OTPF provides one such format1 (Table 10-3). Practitioners become skilled at analyzing activity quickly and completely so that each client benefits from group activity. The role of the practitioner is to adjust the activity, method of performing, or client’s ability so that each member is successful. Practicing analyzing activity with a variety of clients forms the basis for OT intervention. Understanding how conditions or client factors influence participation in a group activity serves to illustrate the complexity of activity. Grading activities refers to adjusting the activity (making it easier for the client to accomplish or more difficult to challenge clients). For example, requiring a client to button only one button of a shirt is easier than having to button all buttons. The practitioner has graded the activity for success. Requiring the client to button the entire shirt while being timed is an example of grading the activity to make it more challenging. Adapting activities refers to changing how the activity is completed by changing the steps (e.g., putting on a shirt with a hook and loop closure instead of buttons). Adapting often involves using equipment to change the activity requirements. Feeding one’s self using adaptive feeding equipment (e.g., built-up handle spoon) is an example of adapting an activity. The planning process is essential for facilitating successful groups and attaining goals. The process for planning group activities begins with a general analysis of the occupation by understanding the client’s occupational strengths and weaknesses. A detailed review of the client factors along with the contexts in which the occupations occure provides additional information to inform the teaching-learning process. Reflecting on the process by evaluating the outcomes and seeking input from members allows the practitioner to plan future groups to promote learning. Figure 10-2 provides a schematic diagram of the process. OT practitioners begin by understanding the population or condition needs, with particular emphasis on the influence the condition has on occupational performance. Achieving a general understanding of the population through a literature search serves as the foundation for specific intervention activities. Box 10-2 provides an example of the literature search findings of an adult population who has experienced the loss of the use of one hand after a stroke.

Occupational and Group Analysis

Adults

Developmental Tasks of Adulthood

Designing Groups for Adults

Area of Occupation

Sample Group Theme

Session Example

Activity of daily living

Dining In

Feeding group using a variety of adaptive equipment, designed to help clients feed themselves independently.

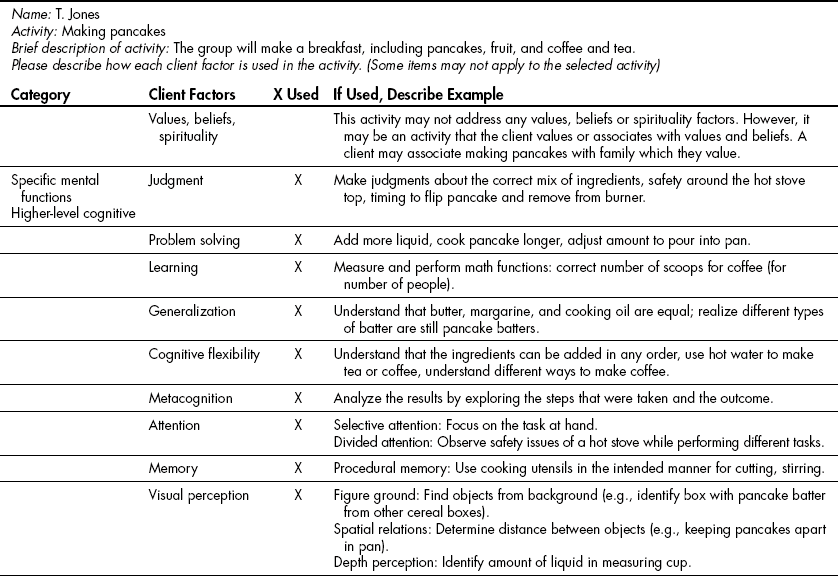

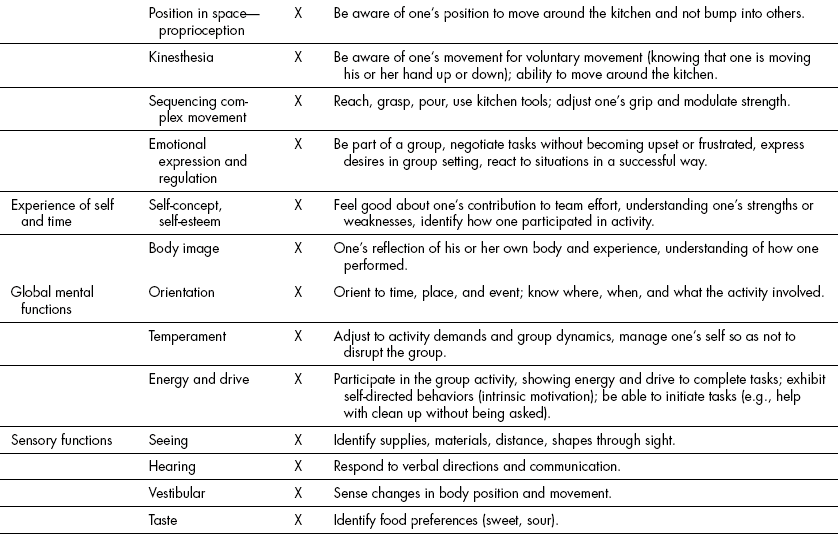

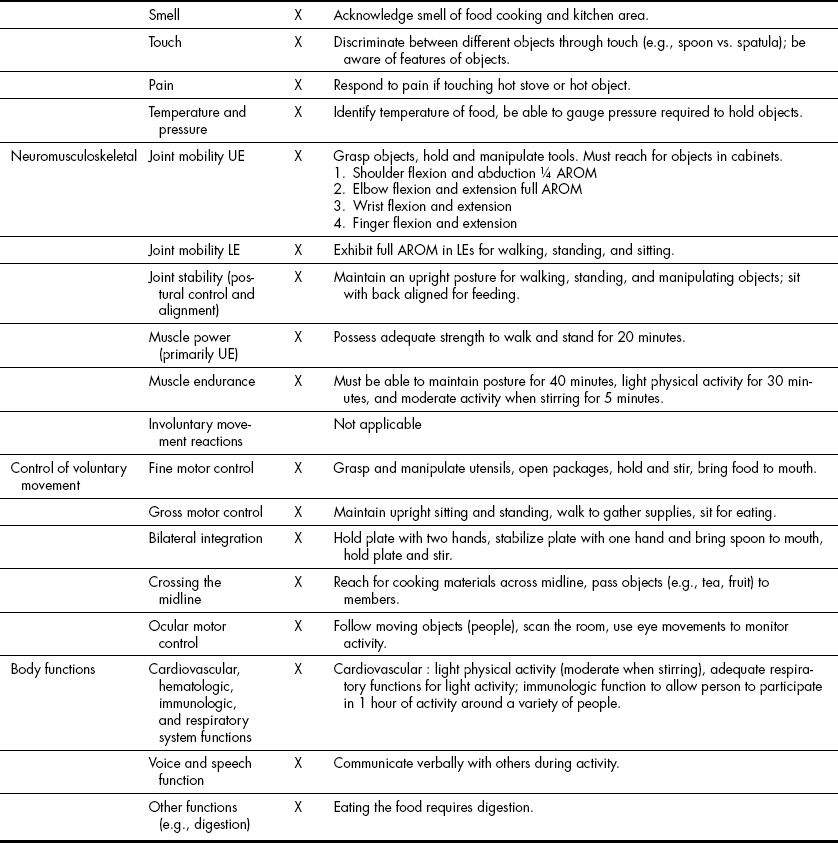

Makeover

Grooming using adaptive equipment, compensatory techniques. Members explore grooming techniques and learn how to adapt for physical limitations. (This group may also work with teens to help them develop self-confidence.)

Community Mobility

About Town

Members practice accessing the bus or subway system. They explore community resources.

Education

Back to the Basics

Members learn strategies to help them in school. They design organizational tools and explore their learning styles so they can develop accommodations for success in educational settings.

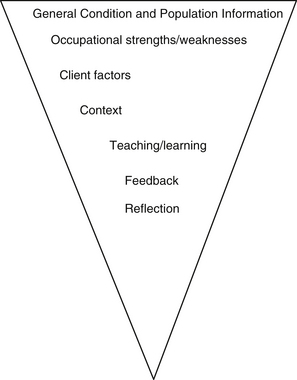

The Planning Process

General Condition and Population

Occupational and Group Analysis: Adults

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access