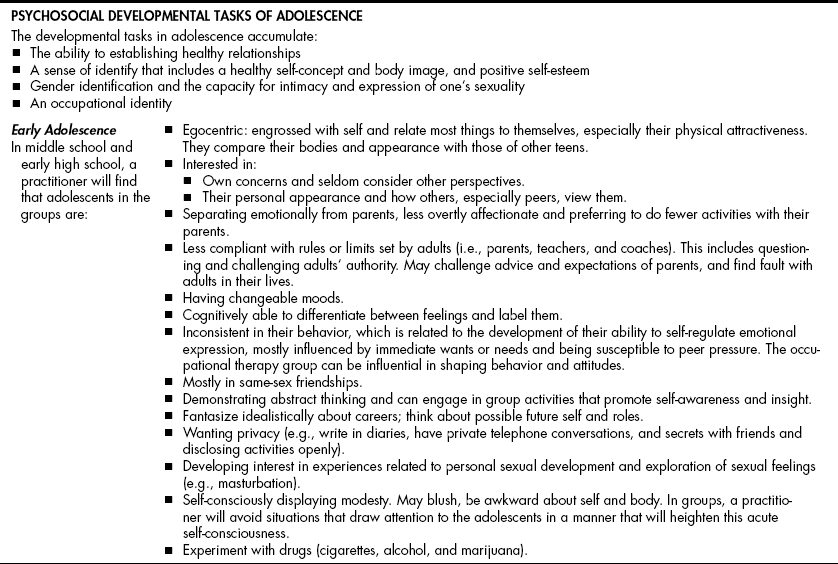

Chapter 9 Psychosocial Developmental Tasks of Adolescents Advantages of Group Interventions for Adolescents Types of Groups and the Frames of References that May be Used to Structure Them Social Learning Theory as a Frame of Reference The Model of Human Occupation as a Frame of Reference Psychoeducational Groups with Adolescents Strength-Based Groups—Activity Groups Strategies for Group Interventions for Adolescents 1 Outline the developmental tasks of adolescents as they relate to group interventions. 2 Identify group needs specific to adolescents. 3 Describe strategies for working with adolescents. 4 Discuss group interventions and frames of reference for adolescents. Practitioners need to consider the developmental tasks associated with adolescence. These include exploring intimacy, sexual and gender orientation, and sexual expression. In middle and high school “fitting in” is important, because identifying with a peer group as friends provides a sense of belonging that is key to successfully navigating the developmental tasks.28 However, there are also pressures from peers, parents, and society to perform and conform. The pressures from peer groups to experiment can include engaging in risky behaviors and expressing group membership through actions such as choice of clothing, drinking, and interests that may create conflict with parents. Although other peer groups may create fewer tensions with parents, the need to follow peer trends and belong is perceived as paramount (Figure 9-1). In adolescence there is a psychosocial vulnerability that can result in behavioral difficulties (e.g., delinquency, participation in criminal activities, social failure, or participation in gangs) or psychopathologic conditions such as the onset of depression, eating disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, self-harming behaviors, and anxiety disorders.11 In contrast, with supportive family, school, and community environments, which include validating adults, healthy psychosocial development results in self-actualization, namely a healthy self-concept, self-esteem, and sense of one’s identity as an autonomous individual. There are three stages of adolescent development (Table 9-1; Figure 9-2). Early adolescence encompasses the middle school years (11 to 13 years old) and the majority of young people in this age group experience puberty (the maturation of the reproductive system with the development of primary and secondary sex characteristics). Middle adolescence includes the high school years between the ages of 14 and 17. This is the period of the most intense psychosocial development, when the salient relationships with friends and other peer-mediated influences displace parental relationships and opinions. Late adolescence, between 17 and 25 years, is a time of consolidation of values, self-identity, and self-efficacy in performance skills required to meet the choices and demands of the roles of early adulthood such as work and forming a stable intimate relationship. TABLE 9-1 Psychosocial Developmental Tasks of Adolescents to Integrate into Group Interventions Sources of data: Radizik, Sherer, and Neinstein.28 Research studies empirically support the effectiveness and importance of group interventions (counseling, social skills training, psychotherapy, and preventive programs) for adolescents.16,17,28,29,33 Adolescents prefer group settings; it is where they learn, develop, and seek support. Their lives are structured around formal, informal, and virtual groups, such as the classroom, the sports team, Facebook, and friendship groups. Group interventions assist adolescents to develop peer relationships in a structured, safe environment and to express themselves without fear of criticism, ridicule, or bullying. In therapy groups, structure and activities that are appropriate for age and development assist adolescents to find their voice, articulate their concerns, and receive support from peers and adults. Adolescents with special needs or disabilities engage in fewer social activities and friendships outside of school. Even adolescents with friends at school report they have less contact with friends outside of school in comparison with their peers.10 Reasons for this discrepancy include not participating in or not excelling in the activities such as sport. During adolescence, social participation and stereotypical characteristics of “physical attractiveness” and interpersonal skills are primary factors of high social status.25,32 Adolescents with disabilities seldom have high social status and those with physical disabilities deal with additional challenges of mobility and community access. The negative consequence of limited participation with peers results in less engagement in the broad range of activities and tasks that promote role and skill development in adolescence (Figure 9-3). Adolescents may be referred to occupational therapy because they are experiencing psychoemotional or behavioral problems. They are often reluctant attendees in the group sessions because they perceive that occupational therapy makes them “different.” At this age teens want to conform to the “typical” image for adolescents in their community, culture, and particular peer group. Already challenged emotionally and lacking in the skills to articulate their thoughts, feelings, and needs, they may demonstrate their reluctance and ambivalence in their behavior rather than verbally express their concerns about being stigmatized. They fear what therapy will involve and mean for them. However, group interventions can also reduce their isolation by challenging the myths that one’s emotions and experiences are unique. They can find peer acceptance, perhaps for the first time, and receive adult guidance and support in a context that also offers avenues to assert power and gain independence.6 Occupational therapy group interventions for adolescents occur in many settings. Groups are offered in schools to enhance school performance or to facilitate transition from high school. Groups providing mental health or behavioral interventions may be based in health, justice, or educational settings. Other groups are delivered in the community, including summer camps, city-supported initiatives for youth, and programming that is an extension of school services. Any of these frames of reference–based groups, outlined here, can be provided in these settings.32 Occupational therapy with adolescents in mental health multidisciplinary settings is often provided in talk-based groups, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or psychodynamic therapy. Social workers, psychologists, and youth workers also use these frames of reference.24,32 Adolescents involved in talk-based therapy benefit from structure. A practitioner uses structure to help adolescents manage their anxiety and lessen their resistance to participating in therapy. Self-disclosure and sharing of experiences and feelings to promote insight and self-understanding can be facilitated using projective activities (self-awareness activities), a strategy that an occupational therapy practitioner brings to talk-based therapy. In projective activities, a variety of media such as art activities, music, movement, or sociodrama are vehicles for self-exploration and self-expression. Through an activity, adolescents express themselves and by talking about the theme of the activity they begin to give a voice to their feelings and concerns. For example, the magazine picture collage, a projective activity used to assess adolescents in mental health settings, provides insights into how they perceive themselves and describe their interests (Figure 9-4).12 Life and social skills are two common areas of occupational performance addressed through group programs. In skill-based programs, goals must clearly delineate the area of occupational performance being addressed.24 The label social skills has become an umbrella term for the interpersonal and communication skills necessary for successful social participation, relationships, and community engagement. However, the performance skills (e.g., social interaction skills, communication skills, and social skills) consist of distinctive areas. Similarly, the frame of reference selected is based on the evidence of its effectiveness to promote development of the targeted skills. The context of the group program is also critical to the facilitation of the skills and the generalization of the learning to adolescents’ everyday occupations. For example, a practitioner planning a group program to develop functional community mobility skills would select an occupation-based frame of reference so that the skills are acquired in the naturalistic setting (the adolescents’ community). Although occupation-based learning in the natural context is optimal, practitioners addressing a limited performance skill frequently select a frame of reference that works on acquisition of the components of skills in a simulated context. Therefore, the psychiatric rehabilitation model may be the choice for a group of late adolescents who need to acquire activities of daily living skills to transition to a group home. We have chosen the category of social skills to illustrate a communication group program that would focus on acquisition of component skills in a simulated context.24,29,33 Box 9-1 provides a description of the aspects of social skills. Selected subareas may be identified and expanded into a specific group program such as assertiveness, anger management, or self-regulation strategies for the classroom setting. This list emphasizes the importance of focusing on a comparable level of social skills and building a group program that is congruent with the performance capacity of the group participants. It is better to limit the focus and achieve skill competency, because the adolescent’s self-efficacy (belief in one’s ability to perform) in social skills builds self-esteem and increases the likelihood of social participation. Practitioners planning to implement social skills groups with adolescents are strongly encouraged to make use of resources available in the health and education literature. Practitioners use task analysis to identify the components of the skills to be addressed. The skills listed in Box 9-1 are divided into behavioral units according to the performance capacity of the adolescent group participants. For example, a group working specifically on communications skills might have sessions on conversing using verbal and nonverbal interactions such as greeting, initiating a conversation, and asking questions.

Occupational and Group Analysis

Adolescents

Psychosocial Developmental Tasks of Adolescents

Advantages of Group Interventions for Adolescents

Types of Groups and the Frames of References that May be Used to Structure Them

Talk-Based Therapy Groups

Social Learning Theory as a Frame of Reference

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Occupational and Group Analysis: Adolescents

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access