Chapter 30. Observation

Sonja Mcilfatrick

▪ Introduction

▪ Structured observational methods

▪ Unstructured observational methods

▪ Role of the observer

▪ ‘Entering the field’: access, rapport and practical considerations

▪ Evaluating observations

▪ Conclusion

Introduction

Parahoo (1997) noted that observation could be considered invaluable for studying human behaviour, either on its own or in conjunction with other research methods. This is because the directness of watching what people do and listening to what they say is fundamentally important to real world research (Robson 1993). This chapter will seek to explore the use of observation as a method of data collection, examining the strengths and weaknesses of using observation as well as some of the ethical and practical considerations. The main types of observation, structured and unstructured, will be discussed along with an exploration of the role of the researcher in observation. Finally, this chapter will detail an example of a study of observation as part of a larger study.

What is observation?

The term observation has been described in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary as ‘the action or process of closely observing or monitoring, and the ability to notice significant details’. Observation is not unique to research and can be considered as part of everyday life. Adler and Adler (1994) noted:

For as long as people have been interested in studying the social and natural world around them, observation has served as the bedrock source of human knowledge. (p. 377)

As a research method, observation involves the researcher watching, listening and recording phenomena systematically (Bowling 2002). Silverman (1993, p. 42) noted that researchers need to recognise the value of using all their senses and the importance of ‘using our ears as well as our eyes during observational work’. An early classic example of this distinct research method was Goffman’s (1961) study of the total institution, where he obtained employment in a psychiatric institution in order to observe it.

Observation can be used in surveys, case studies and experiments, either in isolation or alongside other methods, such as questionnaires and interviews. Observation epitomises the idea of the researcher as the research instrument and involves ‘going into the field’, describing and analysing what has been observed (Mays & Pope 1995). However, it can be argued that observation is a relatively underused research method in nursing (Kennedy 1999). According to Parahoo (1997) this is surprising given the practice base of nursing and the fact that nurses rely heavily on observation during their clinical work.

Why use observation as a method of data collection?

Often the key objective for using observation is to check whether what people say they do is the same as what they actually do. As Hammersley (1990) suggested:

To rely on what people say about what they believe and do, without also observing what they do, is to neglect the complex relationship between attitudes and behaviour. (p. 597)

Other reasons for using observation as a method of data collection may include:

• providing insight into interactions;

• helping to illustrate the whole picture;

• capturing a sense of the context and whole social setting in which people function;

• helping to inform about the influence of the physical environment (Mulhall 2003).

Some phenomena lend themselves well to observation (Polit & Hungler 1995), including characteristics and conditions of individuals, verbal and non-verbal communication behaviours, activities, skill attainment and performance and the characteristics of an environment. Some examples of phenomena that have been studied by observation include: ‘home care for people with dementia’ (Briggs et al 2003); ‘children’s participation in decision-making’ (Runeson et al 2002); ‘men’s experiences of chest pain’ (White & Johnson 2000); ‘social support in nursing homes’ (Patterson 1995); ‘patient dignity in intensive care settings’ (Turnock & Gibson 2001); ‘district nursing decision-making’ (Kennedy 1999); ‘nurses’ role in an operating department’ (McGarvey et al 1999); and ‘interaction between nurses, parents and children in intensive care’ (Endacott 1994).

Structured observational methods

Structured observation can be considered as an approach in which the aspects of the phenomenon to be observed are operationally defined and decided in advance. Structured observations describe behaviours accurately and reliably, remove subjectivity as far as possible (Pretzlik 1994) and set the boundaries of what is to be observed prior to data collection. According to Parahoo (1997), structured observations usually involve quantifying the specific aspects of a phenomenon such as the presence or absence of a particular behaviour and the frequency and intensity with which it happened. Therefore, the development of an observation ‘schedule’ or ‘checklist’ (Box 30.1) is important to define exactly what it is you are trying to observe and the terms to be investigated. For example, in a study of patient exposure in an intensive care unit, Turnock and Gibson (2001) developed an observation proforma to provide information specifically on the following: who was involved in each incident; the areas of the body exposed (such as chest; front genitalia; legs; buttocks); the nature of the intervention (examination; hygiene; elimination); timing of any explanation; length of exposure and the use of screens. This type of proforma can prove useful in avoiding situations when different observers use different terms to describe the same site of exposure.

Box 30.1

Observational checklist

WHERE? The setting: this relates to the actual physical environment. What does it look like? What is the context?

WHO? The participants: description of who is in the setting; the number of people and their roles. How do they behave, dress?

WHAT? Activities and interactions: a description of the daily process of activities. What is actually going on? Is there a clearly defined sequence of activities?

WHEN? Frequency and duration: when did the situation observed begin? How long does it last? Is the situation recurring and if so how often?

WHY? Personal reflection: includes researcher’s thoughts and feelings about what is going on and personal reflections.

Some possible ways to assist the development of an observation framework include: a review of the literature for tried and tested tools, using expert opinion, concept definition and analysis and translating the concept into items or indicators. For example, Barlow (1994), exploring the quality of nursing care provided for sick children, was able to use established quality assurance tools to help provide a focus for some of the elements in the development of a schedule. Some of the categories included:

▪ individualised care/parental involvement;

▪ physical well-being of the child:

safety

infection control

observations;

▪ psychological well-being of the child and family:

comfort and rest

communication.

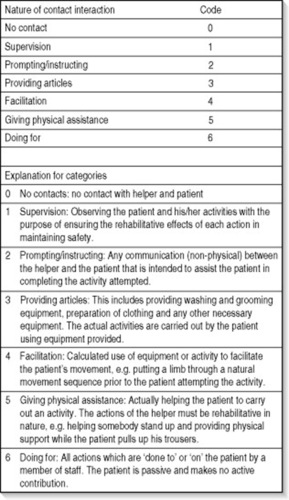

Polit and Hungler (1995) noted that each category needs to be explained in detail, with an operational definition, to enable observers to have clear criteria for assessing the occurrence of the phenomenon under investigation. To develop recording and subsequent analysis further, categories can then be given codes. For example, Booth et al (2001) carried out a non-participant structured observation study to compare the interventions of qualified nurses with those of occupational therapists during morning care with stroke patients. This involved developing an observational instrument (based on previous work) for categorising interaction styles (Fig. 30.1).

|

| Figure 30.1 Structured observational instrument: categories of interaction styles. FromBooth et al 2001, with permission of Blackwell Publishing. |

Observational instruments need to be assessed for content validity and reliability. For structured observations to have validity, this means the observer must observe what they were supposed to observe. It is important that the operational definitions are clear and that the categories employed represent the phenomenon under investigation. One way of assessing content validity of the observation schedule is to give the schedule to a panel of experts for review. Reliability relates to the consistency with which the observer matches a behaviour or activity with the category on the observation schedule, and the consistency of recording it each time it happens (Parahoo 1997). This can involve both intra-observer (one observer at different times) and inter-observer (more than one observer) reliability. The data can then be used to calculate an index of agreement, with values ranging from 0.00 to 1.00, with the higher values indicating more agreement and thereby more reliability. The training of observers has been identified as a crucial aspect in helping to improve validity and reliability (Turnock & Gibson 2001).

The role of the observer in structured observation is non-participative where the observer stands ‘outside’ of what is being observed and tries not to exert any influence on the situation (discussed in a later section). Structured observations adopt mostly a deductive approach when the behaviour or activity is observed against predetermined units of observation. As it is not always possible to observe every behaviour or activity continuously, sampling is required including time sampling or event sampling. Time sampling is where the observer selects time periods when the observations will take place (e.g. an hour at four-hourly intervals over a specified time). For example, suppose a researcher wanted to observe the behaviour of patients and nurses during chemotherapy treatment. During a one-hour observation period they could decide to sample behaviours rather than observe the entire hour. An approach could be to sample randomly 10-minute periods from the total of six periods over the hour. However, it is important that the decisions around the length and number of observations are informed by the aims of the research. Event sampling is where the observer selects pre-specified events for observation (e.g. shift changes in a ward or cardiac arrests). Event sampling usually requires that the researcher has some prior knowledge regarding the occurrence of events. This type of approach is usually preferable to time-sampling when the events of interest for the study are infrequent throughout a day and are at risk of being missed if specific time-sampling frames are selected.

Unstructured observational methods

Unstructured observations are useful for situations where little is known about the phenomenon under investigation or when the existing knowledge is lacking. Mulhall (2003) maintained that the use of the term ‘unstructured’ can be misleading. Observation is unstructured in that it lacks a list of predetermined behaviours. Therefore, unstructured observation can be considered as an inductive, naturalistic approach that is qualitative and flexible in nature. The advantage of the unstructured approach relates to the idea that the more structured quantitative methods can be considered as too ‘mechanistic’ and ‘superficial’ to ‘render a meaningful account of the intricate nature of human behaviour’ (Polit & Hungler 1995, p. 307). According to Adler and Adler (1994), the unstructured type of observation:

… occurs in the natural context of occurrence, among actors who would naturally be participating in the interaction, and follows the natural stream of everyday life. (p. 378)

The unstructured method can be used to look at single cases (case studies) or complex social organisations (ethnographic approach) (Pretzlik 1994). Using this approach, the researcher is considered as the main tool for data collection and analysis, with the purpose of arriving at as complete an understanding of the phenomenon as possible (Parahoo 1997). Pretzlik (1994) noted that unstructured observation allows the observer to take notes about their observations on an ad hoc basis, with the process being left to the observer to determine. A problem with this is that the researcher may be selective in what to focus on, reflecting their personal interest. It is possible that researchers will omit a whole range of data to confirm their own pre-established beliefs, leaving the method open to the charge of bias.

When using an unstructured observational approach, data are recorded in the form of field notes and logs. Field notes can be considered as descriptions and accounts of people, tasks, events, behaviour and conversations and are useful in recording events ‘as they happen’ (Pretzlik 1994). In maintaining field notes it is vital that raw behaviour is recorded alongside the researcher’s interpretation of the meaning of the behaviour. Barber-Parker (2002), exploring patient teaching in an oncology unit, provided an example of keeping observational (teaching activities), theoretical (attempts to derive meaning) and methodological notes (reflecting research questions and self-critique of research procedures) as recommended by Schatzman and Strauss (1973).

Observations can be recorded using audio or video. Atkinson and Hammersley (1994) commented that the use of such technology allows the researcher to assume a ‘privileged gaze’, in which the relationships with the participants become less relevant to the collection of data. However, establishing relationships with participants is important in gaining their agreement to being observed and videotaped. Paterson et al (2003) suggested that the use of video recording can add depth and breadth to observations by providing data that the researcher was not able to access in participant observation, and by supplementing field notes through a retrospective review. Latvala et al (2000) provided an analysis of some of the potential advantages and disadvantages of using videotape recording as a method of observation in psychiatric nursing research. They found that one of the essential advantages of videotaping was the ability to capture many varied, detailed, precise interactions and behaviours. Other advantages included the ability to review situations repeatedly – helping in the analysis of data; a reduction in self-report fatigue and subjectivity; and the inclusion of both verbal and non-verbal information. Some of the limitations relate to mechanical problems with equipment, the influence of the videotape on behaviour and ethical considerations concerning personal privacy, informed consent and respect for the self-determination of psychiatric patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree