Nutrients, including carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, have specific functions within the body. They work together to provide energy, regulate metabolic processes, and synthesize tissues.

Nutrition influences all body systems favorably and unfavorably. Examples of unfavorable effects include the link between cholesterol and heart disease or salt intake and high blood pressure (BP). Favorable effects are many, such as the association of fiber intake with improved GI function and the role of folic acid in preventing neural tube defects.

Nutritional needs vary in response to metabolic changes, age, sex, growth periods, stress (trauma, disease, pregnancy, lactation), and physical condition.

Nutritional supplements may be needed depending on disease states, dietary intake, and other factors.

The types of foods eaten and eating patterns are developed during a lifetime and are determined by psychosocial, cultural, religious, and economic influences.

The nurse works with the registered dietitian to promote optimum nutrition for each patient.

Dietary guidelines were first developed in 1958 and were based on four basic food groups: grains, vegetables and fruits, meat, and milk. In 2010 the Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dietary Guidelines for Americans were restructured and divided the four basic food groups into five food groups, which now consist of grains, fruits, vegetables, protein, and dairy. Although the guidelines have been reformatted, it still holds true that a well-balanced diet consists of foods from each of these groups and is composed of foods low in fat, cholesterol, and sodium and high in fiber (www.dietαryguidelines. gov). See Chapter 3, page 26, for more specific information about the guidelines.

In response to growing scientific knowledge regarding the linkage of diet and disease, the USDA developed the MyPlate Plan (see Figure 20-1). It reflects making food choices for a healthy lifestyle and includes basic information on how to build a healthy plate by cutting back on foods high in solid fats, added sugars, and salt; eating the right amount of calories; and being physically active.

General background information—name, age, sex, family composition, socioeconomic status, occupation.

General health status and any chronic conditions, including diabetes and associated dietary restrictions.

Cultural and religious factors influencing dietary patterns.

Family history of diseases, including diabetes and obesity.

Current medications, over-the-counter products, and herbal supplements.

Food habits.

Typical daily intake, including meal frequency, meal timing, meal location.

Snacking patterns.

Food intolerance or dislikes.

Nutritional supplements, including vitamins, minerals, fortified beverages, and foods.

Alcohol consumption.

Use of specific diets or dietary restrictions.

Food purchase and preparation.

Who purchases and prepares food and where food is purchased.

Facilities for food storage and preparation.

Factors influencing the types of food purchased.

Nutritionally related problems.

General well-being, energy level.

Weight change during the past 6 months.

Difficulty chewing or swallowing, use of dentures.

Change in sense of taste or smell.

Eructation, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain or swelling in relation to food intake.

Bowel habits.

Perform a systematic physical examination, observing for a wide variety of physical findings associated with nutritional status.

Listlessness, apathy.

Poor muscle tone.

Dull, brittle hair; hair may be thin or sparse, easily plucked.

Rough, dry, and scaly skin or dermatitis.

Cheilosis (fissures at angles of mouth).

Stomatitis (inflammation of mouth).

Inflammation and easy bleeding of gums.

Glossitis (inflammation of tongue).

Dental caries and poor dentition.

Spoon-shaped, brittle, ridged nails.

Skeletal deformities such as bowlegs.

Perform anthropometry, as indicated. (Anthropometry comes from the word anthropology and is the science that studies the size, weight, and proportions of the human body to determine body fat mass, lean mass, and nutritional status.) Types of anthropometric measurements include height and weight, skin-fold thickness, and circumferentialtests.

Height and weight are determined on patient admission and are later used as a baseline for comparisons in nutritional status.

Weight should be measured using a consistent and reliable scale and at a consistent time.

Unintended weight loss of more than 10% of body weight during 6 months is considered clinically significant and may be associated with physiologic abnormalities and increased morbidity and mortality.

Body mass index (BMI) is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (see Table 20-1 on page 744).

BMI of less than 18.5 is classified as underweight.

BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is classified as normal weight.

BMI of 25 to 29.9 is classified as overweight.

BMI of 30 to 39.9 is classified as obese.

BMI greater than 40 is classified as extremely obese.

Metabolism is generally faster in younger people and for this reason, babies and children have higher energy requirement needs than adults. Requirement needs are based on many factors including age, gender, activity level, and disease state. Exact measurements of caloric requirements for infants can be obtained by using charts; these estimate the body surface area by height and weight and the standard basal metabolic rate for a given weight (see Appendix B).

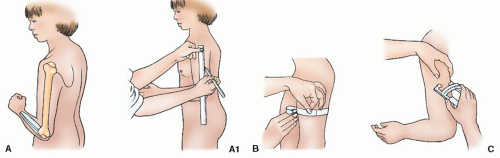

Skin-fold thickness provides an estimate of body fat based on the amount of fat in subcutaneous tissue (see Figure 20-2 on page 744).

Triceps skin-fold thickness:

At the midpoint of the nondominant upper arm (halfway between the tip of the shoulder and tip of the elbow), grasp skin and subcutaneous fat, pulling it away from the underlying muscle, and place the caliper jaws over the skin-fold flap.

Take the reading within 2 to 3 seconds and without using excessive pressure.

Repeat the reading twice and take an average of the three readings to increase accuracy.

Subscapular skin-fold thickness: Grasp the skin and subcutaneous tissue just below the inferior border of the left scapula and measure with calipers, as noted.

Circumferential tests provide information on the amount of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Mid-upper arm circumference (MAC)—an indirect estimate of the body’s muscle mass:

Place a tape measure around the midpoint of the nondominant upper arm and secure it snugly.

To calculate, multiply the triceps skin fold by 3.14 and subtract the product from the MAC.

Adult standards are 16.5 mm for women and 12.5 mm for men.

Table 20-1 Body Mass Index (BMI)* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Serum albumin, prealbumin.

Albumin is a protein made by the liver and is responsible for maintaining blood volume and serum electrolyte balance. The half-life of albumin is about 21 days. A decrease in nutritional status may result in a drop in albumin synthesis. However, in chronic malnutrition, serum albumin levels are typically normal or high.

Prealbumin is also made by the liver and is a more sensitive but expensive test that measures more recent nutritional status. Its half-life is 2 to 3 days.

Hemoglobin—made by the liver; decreased amounts are related to iron-deficiency anemia or other defect in hemoglobin synthesis or dilution of the blood such as during pregnancy.

Serum transferrin—another transport protein made by the liver; responsible for binding iron to plasma and transporting it to the bone marrow. Reduced levels are found in catabolic states and some chronic diseases.

Twenty-four-hour urine creatinine—an increase in this measure indicates increased tissue breakdown.

Twenty-four-hour urine urea nitrogen or total urinary nitrogen—this test can be used to determine nitrogen balance.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTnutritional status. Alternative methods of nutritional support include enteral feeding and parental nutrition. The decision as to which method is used will depend on many factors including the patient’s acuity and nutritional status.

Increased metabolic needs and inability to take adequate oral diet—trauma, burns, cancer, sepsis.

Coma or mechanical ventilation.

Head/neck surgery.

Malabsorption.

Obstruction of esophagus or oropharynx.

Severe anorexia nervosa.

Dysphagia.

Tube feeding formula

Graduated containers

60-mL catheter-tipped syringe

Water

Stethoscope

Gavage feeding bag (optional)

Gloves

Tube feeding bag and tubing and feeding pump

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nasogastric (NG) feeding—tubes are passed through the nose or mouth (orogastric) into the stomach and secured in place.

Tube placement must be verified by x-ray before use. Aspiration of contents for pH or auscultation of air injected through tube has been shown to be of limited value. New techniques that are available include colorimetric carbon dioxide detectors and electronic capnographics, both of which measure end-tidal carbon dioxide to determine if the tube has gone into the trachea.

If there is a question about tube placement in the respiratory tract, the tube should be removed.

Nasoenteric feeding (ie, nasoduodenal or nasojejunal)—tube is passed through the nose into duodenum or jejunum and secured in place. X-ray is usually needed to verify correct tube placement.

Gastrostomy—insertion of a tube surgically, radiologically, or by a percutaneous endoscopic procedure into the stomach.

Gastrostomy button—small device inserted through gastrostomy stoma to allow for long-term feeding with minimal effect on body image.

Jejunostomy—insertion of a tube directly into the jejunum either surgically or by a percutaneous endoscopic procedure. Jejunostomy feedings are generally by continuous infusion using a feeding pump.

Large-bore NG polyurethane tube—size 12 to 18F, used very short term (eg, Salem Sump).

Small-bore NG tube—made of polyurethane, silicone, or polyvinyl chloride with a tungsten-weighted tip or nonweighted tip, size 8 to 12F and 30 to 36 inches (76 to 91.5 cm) long.

Nasointestinal tube—made of silicone, polyurethane, or polyvinyl chloride with tungsten-weighted tip or a nonweighted tip, size 8 to 12F and 40 to 60 inches (101.5 to 152.5 cm) long.

Gastrostomy tube—catheter made of silicone, polyurethane, polyvinyl chloride, or latex; a balloon on the distal end to stabilize tube may be used and ranges from 5 to 30 mL capacity, size 14 to 28F. Adults usually have 20F tubes and children usually start with 14F.

Gastrostomy button—silicone; ranging from 18 to 28F and 1 inch (2.5 cm) long; useful for person wanting minimal alteration in body image.

Jejunostomy tube—size ranging from 5 to 14F with or without a balloon (a balloon may obstruct lumen of jejunum). A plain red rubber catheter is occasionally used as a short-term jejunostomy tube and some gastrostomy tubes may be used for jejunostomy.

Intermittent or continuous infusion of feeding solution by gravity is accomplished by hanging container of feeding solution from an intravenous (IV) pole and adjusting delivery rate by flow regulator.

Continuous feeding by controller feeding pump allows uniform flow, particularly of viscous solutions.

Bolus feeding involves enteral formula poured into barrel of a large (60 mL) syringe attached to a feeding tube and allowed to infuse by gravity.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT

Technique for administration of tube feeding outlined in Procedure Guidelines 20-1.

Signs and symptoms of potential complications.

Need to assess tube placement and residual before each feeding (for gastric feedings only).

Principles of medical asepsis, including careful handwashing, refrigeration of formula, cleaning of equipment with soap and water and thorough drying between feedings.

When the gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube insertion site is well healed, surrounding skin can be cleaned with soap and water.

Gauze dressing can be applied, as needed.

Leakage around tube or signs of peristomal skin irritation should be reported.

Patient cannot tolerate enteral nutrition due to:

Paralytic ileus.

Intestinal obstruction.

Acute pancreatitis and enteral feedings not possible.

Severe malabsorption.

Persistent vomiting and jejunal route not possible.

Enterocutaneous fistula and enteric feeding not possible.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Short bowel syndrome.

Hypermetabolic states for which enteral therapy is either not possible or inadequate, such as burns, trauma, or sepsis.

In these situations, additional components are added to the enteral therapy or individualized solutions are developed to meet the nutritional needs of the patient.

Table 20-2 Complications of Enteral Feeding and Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evidence Base Bankhead, R., Boullata, J., Brantley, S., et al. (2009). A.S.P.E.N. enteral nutrition practice recommendations. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 33(2), 122-167.

Evidence Base Bankhead, R., Boullata, J., Brantley, S., et al. (2009). A.S.P.E.N. enteral nutrition practice recommendations. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 33(2), 122-167.