Chapter 14 Nutrition management

Why is diet important for people with renal disease?

Diet therapy offers the following potential benefits:

• It may be helpful in delaying the need for dialysis.

• Diet can help attenuate many of the complications of renal disease (e.g., phosphorus restriction to aid in prevention of bone disease).

• Adequate protein and calorie nutrition can influence morbidity and mortality in patients with renal disease.

• Quality of life for people with CKD may be improved by individualization of diet to suit lifestyle, ethnic, and socioeconomic variables.

What is the role of the registered dietitian?

The registered dietitian is part of the facility’s interdisciplinary team and, as such, makes recommendations for the patient’s treatment plan. The dietitian will also work with the nephrologist and make a recommendation for the patient’s diet prescription. Patient and family are taught specifics of the diet by the dietitian, who monitors nutrition-related parameters and reevaluates needs. The dietitian is responsible for the primary diet education and functions as a member of the interdisciplinary team. Communication between the dietitian, nurses, technicians, physician, and social worker as to changes in a patient’s medical condition, dialysis treatment, medications, psychosocial situation, and nutritional status is critical to providing optimal patient care.

What are the diet modifications for hemodialysis?

The need for dietary modification after hemodialysis begins is highly individualized depending on such factors as height, weight, nutritional status, the level of residual renal function, laboratory data, intercurrent illnesses, and prescribed medications. Maintenance of good nutritional status, as evidenced by adequate anthropometric measurements and biochemical indices, is critically important during this period. Achieving and maintaining a normal serum albumin level is the primary goal of nutrition therapy for the hemodialysis patient. Various studies have demonstrated that the primary biochemical predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients is a low serum albumin. In the absence of proteinuria or significant liver disease, albumin levels can be maintained with provision of adequate protein and calories. Although the diet is highly individualized, certain diet commonalities do apply to most patients on hemodialysis.

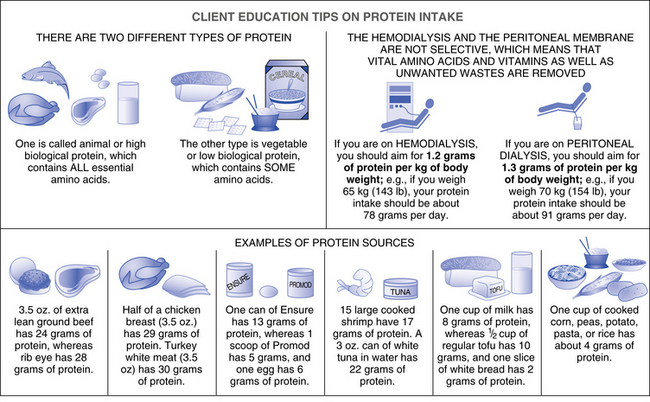

What amount of protein is appropriate for hemodialysis patients?

Protein requirements, as suggested by current research, are thought to be 1.2 ± 0.2 g/kg/day, with the upper end of the range considered appropriate for protein-malnourished patients. In general, at least 50% of this protein should be derived from high biologic–value protein sources, such as meat, fish, poultry, tofu, eggs, dairy, and cheese. Such protein sources contain a full complement of essential amino acids. Examples of low biologic–value protein are fruits, vegetables, legumes, and grains; however, a carefully planned vegetarian diet can be used without compromise of nutritional status (Fig. 14-1). The protein needs of hemodialysis patients are higher than those of the general population, in part because of the loss of 5 to 10 g of amino acid during each hemodialysis treatment.

What about potassium control?

Almost all foods contain potassium, and certain fruits and vegetables are particularly rich sources. When urine output falls below 1000 mL/day, and in some cases before this happens, potassium should be controlled in the diet. An intake of approximately 70 mEq or 2730 mg/day of potassium is safe for most hemodialysis patients. The specific dietary potassium intake depends on the size of the patient, the level of potassium in the dialysate, and other factors that may affect the serum potassium level. Factors other than dietary indiscretion may contribute to hyperkalemia, including severe acidosis, constipation, catabolism, insulin deficiency, and the use of certain medications, such as β-adrenergic–blocking agents and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. The potassium content of selected foods may be found in Appendix C.

How much sodium is acceptable?

An intake of approximately 87 mEq or 2000 mg/day of sodium is appropriate for most hemodialysis patients. Adjustments can be made depending on blood pressure, urine output, and the presence or absence of edema. Hypertension in CKD patients is largely volume related, and dry weight should be constantly reassessed in the hypertensive patient. Renin-mediated hypertension is present in a small percentage of dialysis patients. Appropriate antihypertensive medications, rather than further sodium and fluid restriction, are necessary for this subgroup. The sodium content of specific foods may be found in Appendix C.

What about phosphorus and calcium intake?

Phosphorus intake should be limited to 800 to 1200 mg/day in those with CKD stage 5 (KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Bone Metabolism, 2003). Because phosphorus content of the diet correlates with protein intake, it may be necessary to include some high-phosphorus food to achieve an adequate protein intake. Phosphorus is also controlled by the intake of phosphate-binding antacids, such as calcium carbonate or calcium acetate. Aluminum-containing antacids should be avoided to minimize risk of aluminum bone disease. The calcium-containing antacids are given with meals and snacks, and ideally are titrated to the phosphorus content of the diet. Calcium content in the diet is typically low because foods high in phosphorus also tend to be rich sources of calcium. Calcium supplements, aside from the calcium in the phosphate-binding antacids, may not be necessary to maintain calcium balance when either oral or intravenous 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol is used. Calcium requirements vary considerably depending on the phosphate intake, the use of vitamin D, the calcium content of the dialysate, and the presence of hyperparathyroidism. This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 17.

Are vitamin supplements necessary?

Patients on dialysis may be at risk for deficiencies of certain water-soluble vitamins because of poor nutrient intake, malabsorption, drug-nutrient interactions, altered vitamin metabolism, and dialysis losses. Although evaluation of specific requirements and recommendations is ongoing, supplementation with U.S. Recommended Daily Allowances (U.S. RDA) of vitamins B1, B2, and B12, biotin, pantothenic acid, and niacin, as well as 800 to 1000 mcg of folic acid and 10 mg of pyridoxine (B6) daily is reasonable. The recommendations for folic acid, B12, and B6 continue to be reevaluated in light of information concerning the amino acid intermediate, homocysteine. Elevated levels of homocysteine have been demonstrated to be a risk factor in cardiovascular disease and can be present in patients with CKD. High doses of folic acid, and in some studies B6 and B12, have been shown to normalize homocysteine levels and therefore may have a cardioprotective effect. The efficacy of high-dose supplementation of these B vitamins and the appropriate dosages are yet to be determined in the dialysis population. Vitamin C supplementation is limited to 60 mg/day. Higher doses of vitamin C should be avoided to prevent accumulation of oxalate, an ascorbic acid metabolite. Supplemental vitamin A should be avoided because of potential toxicity related to decreased renal degradation of retinol-binding protein in renal failure. Routine supplementation with a specially formulated vitamin is common in patients with CKD on maintenance dialysis.

How is iron deficiency assessed?

A low mean corpuscular volume may be a late indicator of iron deficiency. If a deficiency is present, intravenous iron administration or oral iron supplementation is warranted. Increasing the iron content of the diet generally does not provide adequate replacement once iron deficiency is identified. Various oral forms of iron are available but may cause gastrointestinal upset. Guidelines for administering intravenous iron and erythropoietin therapy are described in Chapter 17.

Do people on dialysis have to control fat intake?

Dyslipidemia, typically seen as hypertriglyceridemia, combined with low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and normal total serum cholesterol, is the most common lipid abnormality found in dialysis patients. Some patients may present with elevated serum cholesterol, defined as serum cholesterol greater than 200 mg/dL. For these people, it may be appropriate to prescribe a low-cholesterol, low-fat diet.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree