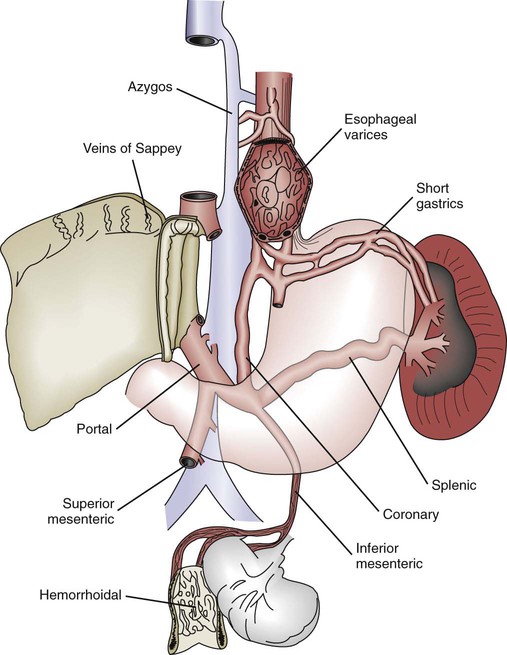

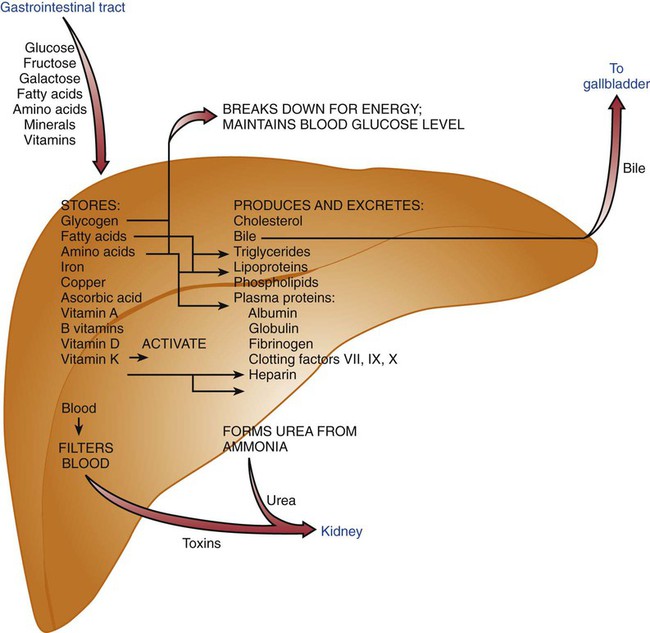

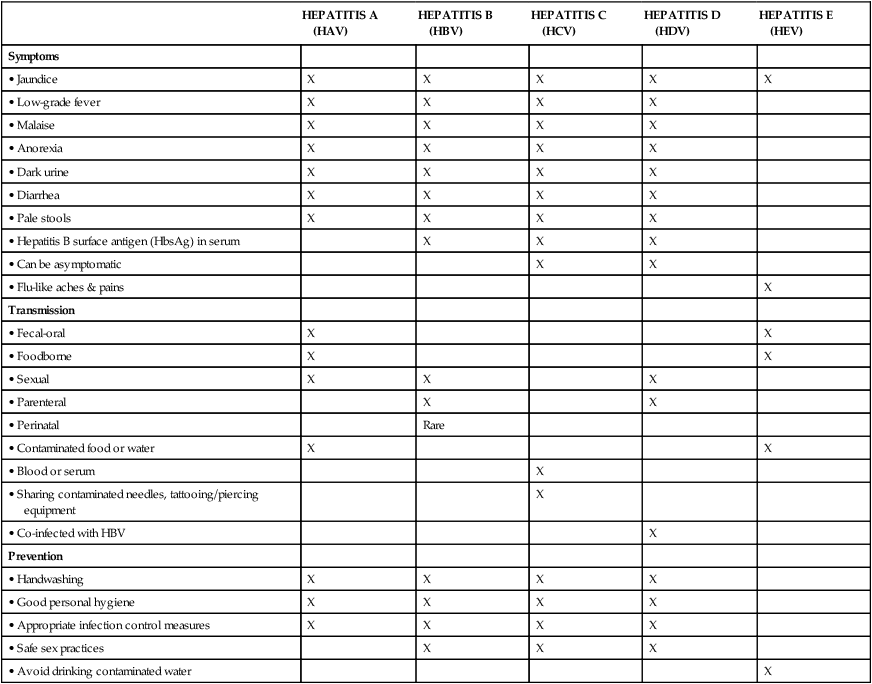

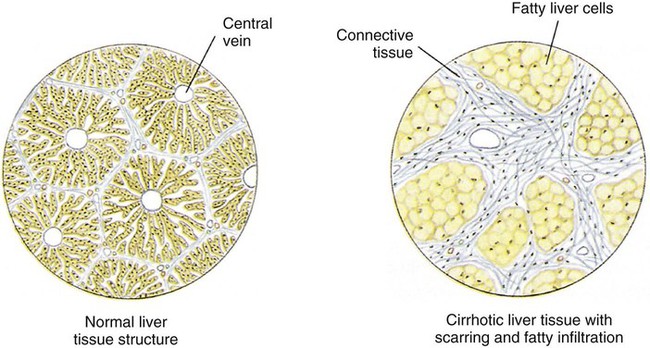

The liver, the largest organ in the body, lies beneath the diaphragm in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 18-1) and is responsible for the majority of biochemical functions that take place in the body. The liver’s management of bile production and its role in intermediary metabolism of carbohydrates, protein, lipids, and vitamins influence nutritional status. Thus it is easy to understand that impaired liver function can result in major imbalances in metabolism and nutritional status. As with many other diseases, progressive decline of nutritional status can further impair liver function. Figure 18-1 summarizes only a few of the liver’s many roles in metabolism and nutritional status. Fatty liver (also called hepatic steatosis) is typically a symptom of an underlying problem. Although it is the earliest form of alcoholic liver disease, it can also be caused by excessive kcal intake, obesity, complications of drug therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, tetracyclines), total parenteral nutrition (TPN), pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, inadequate intake of protein (e.g., kwashiorkor), infection, or malignancy.1 Fatty infiltration of the liver develops when triglycerides build up in the liver tissue, which may eventually produce an enlarged liver. This infiltration is a function of improper fat metabolism. It can be reversed if the causative agent is removed.1 Therefore, if alcohol abuse occurs, then abstinence from alcohol is necessary as part of the treatment and may lead to reversal of the infiltration and prevent further fibrosis or necrosis. Whatever the cause, proper nutrition in the form of a well-balanced diet is important in reversing fatty infiltration. Defined as inflammation of the liver, acute hepatitis can occur as the result of infectious mononucleosis, cirrhosis, toxic chemicals, or viral infection. There are five types of hepatitis that have been characterized, and although symptomatology, clinical signs, and presentation are similar, immunologic and epidemiologic characteristics are different (Table 18-1). TABLE 18-1 COMPARISON OF HEPATITIS VIRUSES Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is typically transmitted through the fecal-oral route (contaminated food or water) but occasionally can be spread by transfusion of infected blood.2,3 It is frequently the result of poor hand washing or stool precautions and is widespread in overcrowded areas with poor sanitation (Box 18-1). Vaccination is recommended for persons at risk for HAV.4 Onset of HAV is rapid—typically within 4 to 6 weeks2—and time to onset of symptoms may be dose related.5 Occurrence of disease manifestations and severity of symptoms directly correlate with the patient’s age.5 Treatment of acute HAV is generally supportive—usually consisting of bed rest—because no antiviral therapy is available. Hospitalization and intravenous (IV) fluids may be necessary for dehydration caused by nausea and vomiting.5,6 An adequate diet that excludes alcohol is recommended.7 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an exceptionally resistant virus capable of surviving extreme temperatures and humidity.6,8 HBV is transmitted via blood and sexual contact.6,8 Globally, the vast majority of cases are transmitted perinatally.6 (See the Cultural Considerations box, Hepatitis B Virus Prevalence Rates, for information about the prevalence of HBV among ethnic groups.) HBV transmits more easily than the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C, with the virus readily found in serum, semen, vaginal mucus, saliva, and tears. IV drug users, patients with hemophilia, those on renal dialysis, and those who have undergone organ transplantation are at increased risk for HBV (Box 18-2). As a result, routine HBV vaccination is recommended for risk groups of all ages and for children up to age 18.4 Average incubation time of HBV is approximately 12 weeks.6,8 As with HAV, the majority of patients are asymptomatic.8 Those who acquire chronic HBV infection (determined by biopsy) can be healthy, asymptomatic carriers but remain infectious to others through parenteral or sexual transmission.6 As with acute HAV, no well-established antiviral treatment is available for acute HBV infection.6 Chronic HBV is treated with interferon alpha and lamivudine to reduce symptoms and prevent or delay progression of chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).6,8 An adequate diet that excludes alcohol is recommended for patients with acute and chronic HBV without cirrhosis.8 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) (previously called non-A, non-B hepatitis) infection is increasing worldwide and is the major cause of hepatitis in the United States.7 It is transmitted through contaminated blood, saliva, or semen, although HCV is predominantly associated with blood exposure (e.g., transfusion, IV drug use,9 acupuncture, tattooing, and sharing razors).10 Onset is usually slow (i.e., approximately 8 weeks), can develop into some form of chronic liver disease,3,6,7 and is a risk factor for liver cancer.2,6 Most cases of acute HCV are asymptomatic; therefore, it is infrequently detected.4 Chronic infection develops in 70% to 80% of people infected with HCV.8 Progression from HCV to cirrhosis may take 10 to 40 years.6,7 A more rapid disease progression is observed in those infected with HIV or HBV, people with alcoholism, men, and those who acquired the infection at an older age.7 Treatment goals include the following6,7: • Decrease viral replication or eradicate HCV. • Delay fibrosis and progression to cirrhosis. • Ameliorate symptoms such as fatigue and joint pain. • Prevent hepatic decompensation and obviate liver transplantation. Chronic HCV is treated with a combination therapy of interferon alpha and ribavirin.6,7 No special diet is recommended. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) can only occur if an individual with HBV is subsequently exposed to HDV (co-infection or superinfection).2,3,10 The incubation period is 21 to 45 days but may be shorter in cases of superinfection.10 Clinical course varies, ranging from acute, self-limiting infection to acute fulminant liver failure.10 HDV is found throughout the world but is prevalent in the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, Amazon basin, Samoa, China, Japan, Taiwan, and Myanmar (formerly Burma).2,3,10 Of those infected with HDV, 90% are likely to be asymptomatic.10 Parenteral transmission is understood to be the most common means of infection,6,10 making IV drug use a risk factor.10 Treatment is composed of support for the most part.10 Patients co-infected with HBV and HDV are less responsive to interferon therapy than patients infected with HBV alone.6 Diet does not need to be restricted.10 Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an enterically transmitted (oral-fecal route), self-limiting infection.6,11 Prevalence of HEV in the United States is generally attributed to travel in endemic areas11 (e.g., South, Southeast, and Central Asia; Africa; Mexico6; and India11). Predominating factors for transmission include tropical climates, inadequate sanitation, and poor personal hygiene. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 60 days, and symptoms include myalgia, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, weight loss (typically 5 to 10 pounds), dehydration, jaundice, dark urine, and light-colored stools.11 Therapy should be predominantly preventive. Travelers to endemic areas should avoid drinking water or other beverages that may be contaminated. Uncooked fruits or vegetables should not be eaten. No vaccines are available for HEV.11 Once infection occurs, therapy is limited to support.6,11 Patients should receive adequate hydration and electrolyte repletion. Hospitalization may be necessary for those unable to maintain an adequate oral intake.11 Oral feedings should be initiated as soon as possible, with frequent feedings high in kcal and in high-quality protein (see Chapter 14), to promote adequate intake and minimize loss of muscle mass. Adequate protein, 1.0-1.2 g/kg body weight, is recommended for most persons. Dietary fats should not be limited unless they are not well tolerated (e.g., steatorrhea). Fat plays an important role in providing concentrated kcal and making food taste better, which is important when trying to get a lot of kcal into a patient who probably doesn’t have an appetite. Fluid intake should be adequate to accommodate the high protein intake unless otherwise contraindicated. Supplementation with a multivitamin that includes vitamin B complex (especially thiamine and vitamin B12 because of decreased absorption and hepatic uptake of these vitamins), vitamin K (to normalize bleeding tendency), vitamin C, and zinc for poor appetite is recommended.12 Abstinence from alcohol is imperative. Cirrhosis is a chronic degenerative disease in which liver cells are replaced by the buildup of fibrous connective tissue and fat infiltration (fatty infiltration; Figure 18-2). This damage can be the result of a variety of reasons, including the following: • Alcoholic cirrhosis (see the Health Debate box, Alcohol: Proscribe or Prescribe?) • Hepatitis (postnecrotic cirrhosis) • Metabolic disorders (Wilson’s disease or hemochromatosis) Esophageal varices are usually the result of collateral circulation that develops around the esophagus when normal blood flow through the liver is blocked (Figure 18-3). Blood vessels tend to enlarge and bulge into the lumen of the esophagus, where they may rupture. This bleeding tends to recur and can eventually be fatal. Patients with esophageal varices should eat soft, low-fiber foods. Another complication of cirrhosis, ascites, is the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Body fluid is trapped in a third space from which it cannot escape.2 This causes the characteristic swollen or distended abdomen often seen in patients with cirrhosis.

Nutrition for Disorders of the Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Liver Disorders

Fatty Liver

![]() Viral Hepatitis

Viral Hepatitis

HEPATITIS A (HAV)

HEPATITIS B (HBV)

HEPATITIS C (HCV)

HEPATITIS D (HDV)

HEPATITIS E (HEV)

Symptoms

• Jaundice

X

X

X

X

X

• Low-grade fever

X

X

X

X

• Malaise

X

X

X

X

• Anorexia

X

X

X

X

• Dark urine

X

X

X

X

• Diarrhea

X

X

X

X

• Pale stools

X

X

X

X

• Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) in serum

X

X

X

• Can be asymptomatic

X

X

• Flu-like aches & pains

X

Transmission

• Fecal-oral

X

X

• Foodborne

X

X

• Sexual

X

X

X

• Parenteral

X

X

• Perinatal

Rare

• Contaminated food or water

X

X

• Blood or serum

X

• Sharing contaminated needles, tattooing/piercing equipment

X

• Co-infected with HBV

X

Prevention

• Handwashing

X

X

X

X

• Good personal hygiene

X

X

X

X

• Appropriate infection control measures

X

X

X

X

• Safe sex practices

X

X

X

• Avoid drinking contaminated water

X

Nutrition Therapy

Cirrhosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nutrition for Disorders of the Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

oz hard liquor.

oz hard liquor.