CHAPTER 21 Nutrition and health

Introduction

Nutrients and water are essential for existence. An adequate intake of nutrients and water is required to maintain physiological function, to allow for growth and maintenance of tissues, and to provide energy to meet the demands of daily living (see Ch. 20). Although a biological necessity, eating and drinking have significance beyond the merely physiological, forming an important part of social and psychological well-being. Meals are used as a time for people to come together, food or drink may be offered to make a guest feel welcome, and formal meals are a feature of many family, religious or national ceremonies.

The importance of the role of the nurse in ensuring nutritional needs are met is well recognised. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) identifies nutrition as a component of the Essential Skills Clusters for pre-registration nursing programmes (NMC 2007). The responsibilities of the nurse concerning nutritional care are extremely varied and range from preventing malnutrition to caring for the malnourished. Nurses play a more minor role in the preparation and serving of food to individuals in their care than they have done in previous years. Changes in food delivery and serving methods have acted to reduce the nursing input required at mealtimes. In many areas there is a necessary delegation of responsibility concerning mealtime care to health care assistants or other staff. However, it must be remembered that it is the qualified nurse who is responsible for ensuring food is provided, as appropriate, to the patient in their care.

This chapter will consider principles of nutritional science, public health nutrition and the nutritional care of individuals by nurses. The principles of nutritional science are only briefly considered in this chapter and the reader is advised to obtain a good understanding of the form and function of macronutrients and micronutrients (see Further reading, e.g. Geissler & Powers 2009).

Principles of nutritional science

![]() See website for further content

See website for further content

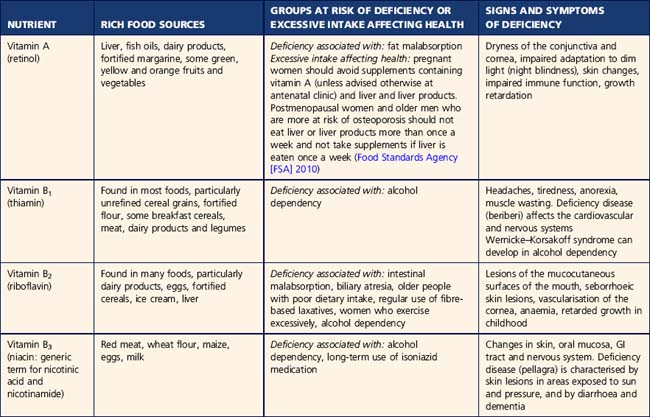

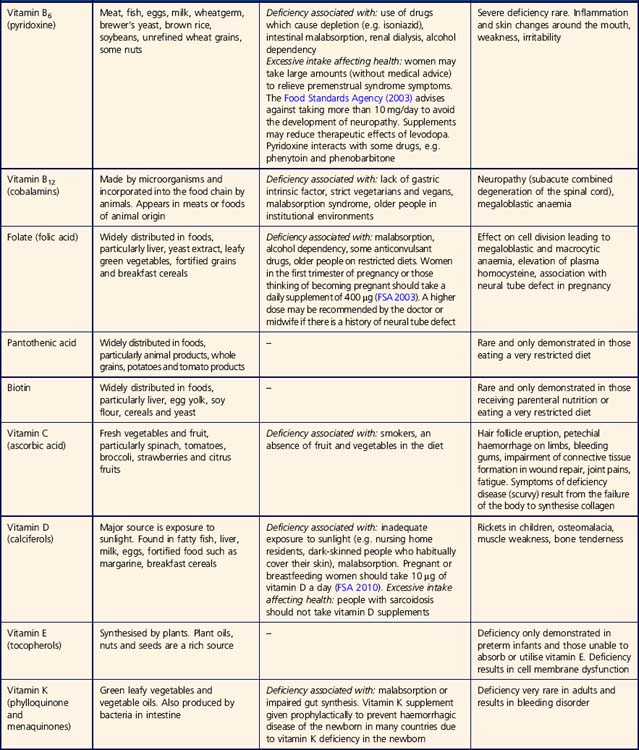

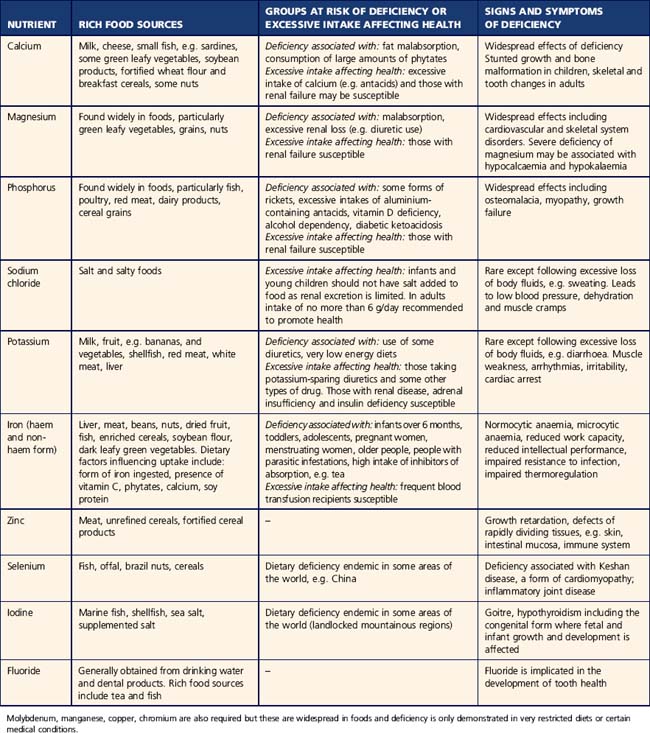

Table 21.1 outlines the vitamins required by the body, and gives details of rich food sources, at-risk groups and symptoms of deficiency and Table 21.2 provides similar information about some of the minerals.

In the UK, estimated nutritional requirements (EARs) for different groups of people within the population have been established (Department of Health [DH] 1991) and are termed dietary reference values (DRVs). Nutritional requirements vary across the lifespan. Infants and children require sufficient nutrients to grow and develop. Requirements for some nutrients are increased pre-conception (folic acid), during pregnancy (folic acid in the first 12 weeks) and whilst breast feeding, and also change with ageing (e.g. vitamin D and calcium). It is important to recognise that dietary reference values are not recommendations for intake by individuals but are estimates for healthy populations only; within a clinical setting the advice of a dietitian must be sought.

Public health nutrition

The diet

The diet consists of the foods people eat from day to day. Although foods containing all known nutrients can be formulated, no single naturally occurring food can meet all the daily nutritional demands. Different types of food contain different proportions of macro- and micronutrients and, therefore, a range of foods is necessary to provide the daily requirement of individual nutrients. The diet should supply all the necessary nutrients in sufficient quantity, whilst avoiding excessive intake. There is considerable debate about the safety of some vitamin and mineral supplements that are not medically prescribed (Food Standards Agency [FSA] 2003). For up-to-date recommendations on the intake of particular nutrients see Useful websites (e.g. FSA www.food.gov.uk and www.eatwell.gov.uk). Government guidelines on dietary intake recommend an intake thought to promote maximum health for the population. For the UK these recommendations include a fat intake of less than 35% of dietary energy intake, of which no more than one third should be in the form of saturated fats, and a carbohydrate intake of approximately 50% of dietary energy intake (DH 1994). A salt intake of less than 6 g/day for adults is also recommended (FSA 2009a).

It is important to consider factors which influence food intake of populations and individuals. At a global level, government policies influence what a population eats because food supply and legislation is essentially determined by government policy. For example, the fortification of foods or water with particular nutrients is a feature in many countries and is usually managed at a central government level, e.g. fortification of flour with calcium. The policy for food labelling which can influence individuals’ choice is determined centrally. Within a country, there are generally regional and socioeconomic differences in dietary intake which can influence what individuals eat, for example, women with low incomes in the UK are more likely to eat low amounts of fruits and vegetables, whole grains and fish, and higher amounts of sugar and sweetened drinks compared with more affluent women (Anderson 2007).

Food safety

Older people and children are particularly susceptible as they are less able to withstand the consequences of food-borne illness, such as prolonged nausea and vomiting. The Food Standards Agency (2009b) outlines that five food-borne bacteria account for the majority of cases of food-borne illness. These are salmonella, campylobacter, E. coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium perfringens. Viruses may cause food-borne disease but they are more likely to be spread from person to person.

Nurses must ensure that Food Hygiene Regulations are adhered to in areas where the RN is responsible for care delivered at both a group and individual level by following guidelines on storing and serving food and drink (Box 21.1).

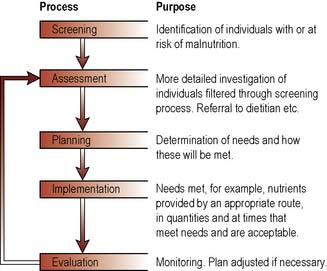

Nutritional screening and assessment

A number of national publications (Nursing and Midwifery Practice Development Unit 2002, DH 2010, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE] 2006a) have highlighted the need for nutritional screening and assessment, and local guidelines for nursing practice have been developed from these. Nutritional screening aims to identify those with, or at risk of, malnutrition and can highlight potential causes. If an individual is considered to be at risk of or to have malnutrition, then a more detailed assessment must be undertaken. A variety of health care professionals may undertake this assessment depending on the type of problem identified at screening. The majority of patients will be referred to the dietitian if malnutrition is suspected. However, referral to another health care professional may also be appropriate; for example, referral to the speech and language therapist (SLT) if a swallowing deficit (dysphagia) is identified.

NICE (2006a) outlines that hospital inpatients, outpatients, people in care homes and people attending GP surgeries should be screened for malnutrition (guidelines for those >18 years). They should be screened on admission and subsequently assessed weekly for inpatients or more frequently if there is clinical concern (NICE 2006a).

![]() See website Critical thinking question 21.1

See website Critical thinking question 21.1

Specific guidelines concerning screening and assessing for eating disorders (NICE 2004) and obesity (NICE 2006b) are also available.

Screening and assessment allow identification of needs, planning of interventions and setting of goals (McLaren & Green 1998). Following this, interventions can be implemented. As always, interventions should be recorded and regularly evaluated and modified as required. Screening and assessment can also establish a baseline from which to monitor changes in status. There are five principal methods of screening or assessing for nutritional status:

Anthropometric tests

Percentage weight change can be calculated using the equation:

Weight considered in relation to height gives a more accurate assessment of the degree to which a person is under- or overweight than weight alone. Body mass index (BMI) is commonly used to assess weight in relation to height. This is simply the body weight in kilograms (kg) divided by the height in metres squared (m2). For example, someone with a body weight of 57 kg and a height of 1.62 m has a BMI of 57/1.622 = 21.7 kg/m2. Height can be difficult to determine, due to factors such as spine curvature and inability to stand. An estimation of height can be made, for example by using ulna length (Elia 2003).

The International Obesity Task Force (2003) has defined the following BMI categories:

When using BMI with older people the resulting plan and intervention need to be carefully considered as the usefulness of BMI as a predictor of risk of morbidity and mortality in the very old has been questioned (British Dietetic Association 2003).

Waist circumference can be used to assess the amount of fat located in the abdominal region. This measure is increasingly being used to screen for cardiovascular risk in primary care. Men with a waist circumference >102 cm and women with a waist circumference >88 cm should be advised that weight reduction would be beneficial (Lean 2000).

Nutritional screening tools

Nutritional screening tools use risk factors that may lead to or be associated with malnourishment and are similar in format to a pressure ulcer risk assessment tool (see Ch. 23). They are typically in questionnaire format and are useful as an aide-mémoire for screening and as a record of information. An appropriate plan of action is identified by some. Of the many nutritional screening tools published, only a few have undergone rigorous testing of reliability and validity (Green & Watson 2005). The British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) has introduced a valid and reliable screening tool for use by nurses in all areas of clinical practice (Elia 2003): the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST). NICE (2006a) has endorsed the use of this tool. Accurate nutritional assessment relies on utilisation of data from a number of sources. Data from only one source can be open to misinterpretation due to the many factors, such as disease processes, that can influence individual parameters. A combination of two or more measures obtained from dietary history and intake, clinical examination, functional tests, anthropometric measures and biochemical tests is required to gain an accurate picture of an individual’s nutritional status. The methods described above may be used by nurses in the context of a busy clinical environment. Other methods can be employed by dietitians and other health care professionals in the clinical environment and research settings (Geissler & Powers 2005).

Refeeding syndrome

If the patient is very malnourished problems can arise from sudden feeding, known as refeeding syndrome. This is caused by a rapid shift of electrolytes, glucose and water from extracellular to intracellular compartments, and can cause deficits in the extracellular fluid. As the syndrome can be life threatening it is crucial that anyone at risk of refeeding syndrome is identified before nutritional intervention is given so that appropriate intervention can be planned. A person who has had very little food intake for more than 5 days is at some risk. NICE (2006a) recommends that people who have eaten little or nothing for more than 5 days should have nutritional support at no more than 50% of requirements for the first 2 days. Following this the nutritional support can be increased if clinical and biochemical monitoring reveals no refeeding syndrome. See Further reading, e.g. Mehanna et al 2008.

Nutritional intervention

A healthy diet

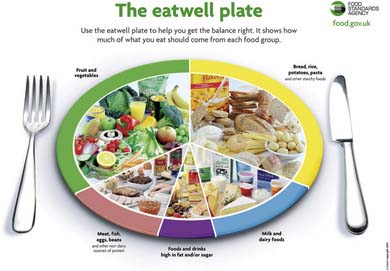

The diet which is currently recommended to promote the health of the general population in the UK is shown in Figure 21.2.

The pictorial representation is termed the ‘plate model’. It illustrates five food groups, and the proportion in which each group should be consumed can be used as a health promotion tool. Such a diet is sometimes termed a ‘balanced diet’, i.e. it provides the appropriate amounts of all nutrients in the correct proportions to meet the requirements of the body. This diet consists of 33% vegetables and fruit, 33% complex carbohydrate, 12% protein-containing foods, 15% dairy products or similar foods and 8% fat- and sugar-containing foods. Current recommendations suggest that individuals eat at least five or more portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables a day (FSA 2009c). The type of diet outlined above is not suitable for those under 5 years of age or those following a diet prescribed by the dietitian.

The Food Standards Agency provides Eight Tips for Eating Well:

(Reproduced from the Food Standards Agency 2009d with permission.)

Obesity

Obesity is the condition of excessive accumulation of fat in the body, leading to an increase in weight beyond that considered desirable. Obesity quite simply results when intake of energy is greater than energy usage. However, the reasons why this happens are complex. Although many people have the genetic propensity to develop obesity, the propensity does not mean the person will become obese; customary diet and lifestyle play a major role (Ulijaszek & Lofink 2006). Rarely, obesity may result from a medical condition, such as hypothyroidism (see Ch. 5, Part 1).

Obesity is considered a major world health problem as the number of people who are obese is rapidly escalating (World Health Organization 2006). Obesity is associated with many common disorders such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (NICE 2006b). Individuals with obesity may also be subject to psychological distress and social penalties.

Treatment of obesity

There are a number of approaches to the treatment of obesity. Currently, few specialist obesity clinics exist and most people with obesity who seek help from health care professionals are assessed and managed by the primary care team. NICE (2006b) recommends multicomponent interventions for individuals which involve behaviour change to increase physical activity level, improvement of eating behaviour and quality of diet, and reduction in energy intake. Treatment programmes within the primary care setting should be individualised and involve assessment and goal setting. The Department of Health in London has produced a comprehensive package of material for health professionals as well as information for patients and clients concerning the management of obesity (DH 2009a). The package includes obesity care pathways for adults and children. Assessment of the patient or client by the nurse should follow the guidelines outlined by NICE (2006b) and include assessment of readiness to change.

Dietary change

NICE (2006b) outlines that a diet containing 600 kilocalories less than the person needs to stay the same weight or a diet that reduces energy intake by lowering the fat content should be recommended. Low energy (1000–1600 kcal) and very low energy diets (less than 1000 kcal/day) may be used in the short term. In the longer term a diet consistent with other healthy eating advice is recommended.

There are many types of diet published, advocating various types and combinations of foods.

NICE (2006b) does not recommend the use of very restrictive and nutritionally incomplete diets because they may be harmful and ineffective in the long term.

Physical activity

Increased physical activity can facilitate weight management (Mulvihill & Quigley 2003). Some individuals may be unable to increase their physical activity levels due to their medical condition, and the advice of the doctor should be sought. Adults should undertake 30 minutes (or more) of moderate-intensity physical activity on five or more days of the week. This can be as one session or several sessions of ten minutes or more (NICE 2006b). NICE (2006b) suggests that people who have been obese and lost weight may need to do 60–90 minutes of moderate activity a day. Activity within the daily routine, e.g. walking rather than driving, should be encouraged. Resistance training can also help, as it will conserve muscle mass and maintain resting metabolic rate as weight is lost (Hunter et al 2008). Exercise on prescription may also be a useful way of promoting activity level (DH 2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree