Chapter 31 NUTRITION

NUTRITION

While eating has psychosocial and cultural significance in life, the major roles of food intake are to provide nutrients necessary for the development and growth of cells and the replacement of substances required by cells to maintain efficient body function. Information about the ingestion and digestion of food and the absorption of nutrients, is provided in Chapter 33. After the digested nutrients have been absorbed into the blood and lymph, they are distributed to the cells for further chemical processing, which releases the energy necessary for body function. The process of metabolism converts the nutrients into chemical forms that produce energy and rebuild body tissue. The two phases of metabolism are anabolism (or constructive phase), when simple substances derived from the nutrients are converted into complex substances that can be used by the cells; and catabolism (or destructive phase), when these complex substances are reconverted into simpler forms to release the energy necessary for cell function.

Many factors influence a client’s pattern of eating, and include:

NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

A client’s nutritional status is assessed by obtaining information about their appetite, food preferences, height and weight and level of activity, and from observing their general appearance. Observation of a client’s general appearance provides information about their general state of health and their nutritional status. Some characteristics of altered nutritional status are presented in Table 31.1. Assessing the client’s eating pattern and their nutritional status may identify problems or risk factors.

TABLE 31.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF ALTERED NUTRITIONAL STATUS

| General | Cachexia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, cardiomegaly, weight loss or gain |

| Hair | Dull, dry or brittle hair; hair thinning or loss |

| Nails | Brittle, broken, ridged or spoon shaped. Pale nail bed |

| Skin | Dry or scaly, bruising or petechiae unrelated to trauma, ulceration, abnormal colour changes, dermatitis |

| Oral mucosa | Pale mucous membrane, ulceration and cracking, ketone-smelling breath |

| Lips | Angular stomatitis, cheilosis |

| Tongue | Swollen or smooth tongue, atrophic papilla, cracking or fissuring |

| Gums | Spongy and/or bleeding gums, gum recession |

| Teeth | Mottled, dental caries, absent teeth |

| Conjunctiva | Pale to reddish-pink |

| Vision | Diminished visual acuity or loss |

| Cardiac | Tachycardia, cardiomegaly, palpitations, angina |

| Muscles | Muscle wasting, atrophy, diminished strength or tone, constipation |

| Skeleton | Curvature of arms or legs, altered gait, shortened stature, fractures |

| Neurological | Altered mood or affect, reduced concentration span, coordination, sensory or motor activity and reflexes, vision loss |

| Urine | Ketonuria, urobilinogen, haemoglobinuria, haematuria |

In addition to the physical characteristics associated with poor nutritional status, psychological symptoms may be evident. A client with a poor nutritional status may experience irritability, lethargy, apathy or inability to concentrate. It is possible, however, that these symptoms and the physical signs presented in Table 31.1 may be related to an underlying condition and/or the client’s nutritional status.

Certain groups of clients may be more at risk of a poor nutritional status, including those who are:

HEALTHY BALANCED DIET

Nutritional needs of infants and children

Throughout all stages of development, a healthy balanced diet is necessary to provide the nutrients required for the body’s needs. For information on maternal and newborn nutrition, see Chapter 49.

The school-age child

During the first 12 months of life a foundation is laid down for good dietary practices. By the time the child is of school age, eating patterns are usually firmly established. As the child grows and develops, their tastes can change — foods that were previously enjoyed may be refused, while the child may acquire a taste for other foods, due in part to social interaction and their changing physiological needs and subsequent sensory changes.

Adolescence

From 10 years of age, children’s bodies are developing rapidly to prime the body for reproduction. A pre-puberty growth spurt occurs earlier in girls than in boys, as they store more fat, which initiates adolescence faster (see Chapter 16 for further information). During this time there can be major changes in their selection and volume of food; hormones alter senses such as taste to enable the adolescent to adapt to obtain changing nutrient requirements. Some clients at this age may be vulnerable to self, peer and social influences that may alter their perception of appearance and self-worth and drastically modify their eating habits (see ‘Eating disorders’, later in this chapter).

ENERGY REQUIREMENTS

The two units of measurement that specify the energy value of food are calories and joules. A calorie is defined as the amount of heat required to raise 1 gram of water by 1°C. A joule, which is the standard international (SI) unit of energy and heat, is equivalent to the amount of work performed when a 1 kg mass is moved 1 m by the force of 1 newton. One calorie is equal to 4.184 joules. As joules are very small units, it is more convenient to measure food energy in terms of kilojoules. One kilojoule (kJ) is 1000 joules. (For further units of measurement, see Appendix 2.)

The energy value of the three major types of nutrients are:

BMI = Weight in kilograms divided by height in metres2

For example, the BMI of a male who is 6 feet (1.83 metres) tall and weighs 115 kg is:

NUTRIENTS

WATER

Water is a chemical compound obtained by the body from food and fluid and as a result of the metabolism of protein, fat and carbohydrate in the tissues. Water constitutes about 60% of the total body weight and is present as intracellular fluid and extracellular fluid. Water is also the basis of all body secretions and excretions.

FIBRE

Dietary fibre, often referred to as cellulose, is the fibrous parts of food that the digestive system has difficulty in digesting. Fibre creates bulk in the stools, which enhances defecation and is used to prevent or minimise symptoms of certain disorders, such as haemorrhoids, diverticular disease, formation of gallstones, simple constipation and intestinal cancer. Foods with a high fibre content are fruits, vegetables and wholegrain products. Clinical Interest Box 31.1 provides discussion on the effects of constipation on the older client.

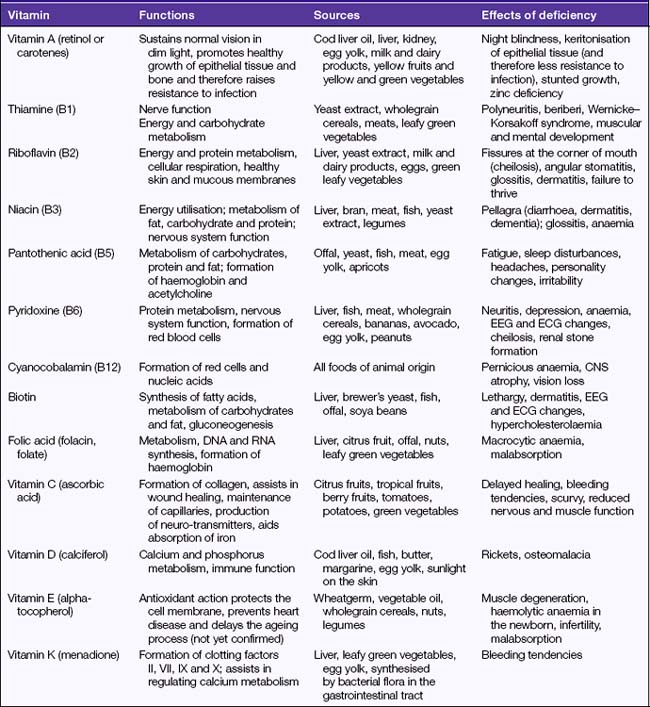

VITAMINS

Excessive intake of vitamin A over long periods can result in hypervitaminosis A, a condition characterised by yellow discolouration of the skin (often mistaken as jaundice), loss of appetite and dry itchy skin. Excessive intake of vitamin B may result in allergic-type reactions. Hypervitaminosis D may occur if excessive amounts of vitamin D are taken and is characterised by nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, general irritability and severe impairment of kidney function. In normal circumstances a healthy balanced diet will provide the body with sufficient quantities of all vitamins without the need for supplemental vitamin ingestion. Table 31.2 describes the functions and effects of vitamin deficiencies.

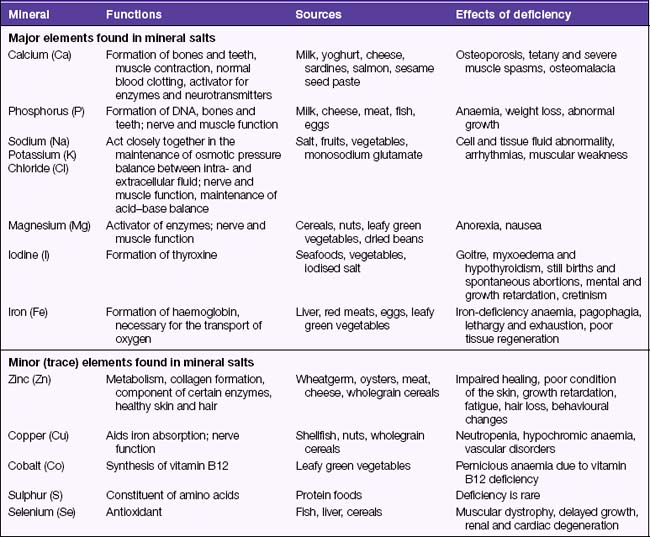

MINERAL SALTS

Mineral salts are a group of compounds that play an important role in metabolism, maintenance of blood pressure, cardiac function, fluid and electrolyte balance, acid–base balance and the regulation of other body processes. Storage and processing of food does not alter its mineral content, although mineral salts may be lost when food is soaked or cooked in water. The elements that mineral salts contain are classed as either major or trace elements; trace elements are present in only minute quantities in the body. A mineral salt that has the property of being a conductor of electrical current is referred to as an electrolyte. The functions and effects of mineral salt deficiencies are listed in Table 31.3.