CHAPTER 29 Nursing the critically ill patient

Introduction

Critical care is a constantly emerging and costly speciality that has grown as a response to developments in medicine and surgery (Department of Health [DH] 2000). The case mix is varied, and admission to critical care can result from trauma, disease adverse events or surgery. All patients will require some kind of organ support or intervention (DH 2005). Critical care is classified into three levels outlined in Box 29.1.

Box 29.1 Information

Levels of critical care support (Department of Health 2000)

The term ‘critical care’ encompasses intensive care patients categorised as level 3, and high-dependency patients (level 1 and 2 in the Department of Health guidelines). Critical care in recent years has expanded to provide services throughout the hospital which are termed ‘outreach services’. The service has been developed in many acute hospitals to meet the needs of critical care provision ‘without walls’; this facilitates early identification of at risk patients and timely transfer to critical care services (Hancock & Durham 2007). The specialist teams made up of specialist nurses and medical staff are available to all wards and departments for advice and to review patients at risk of deterioration. Early warning scoring systems have been implemented in many hospitals to help identify patients at risk. These assessment tools use physiological parameters to assess the patient. An abnormal parameter such as a respiratory rate >30 would give a high score and identify to ward staff the need for support with the management of the patient. (See Further reading, ALERT Manual 2003. The text gives guidance of identifying at risk patients.)

Patient safety

Patient safety is high on the agenda of Government and professional bodies. The acquisition of health care associated infections such as meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile receives a great deal of media attention, and developing strategies to avoid harm is crucial (NICE 2007). Critical care practitioners have developed evidence-based ‘care bundles’ in order to optimise care. Care bundles are a group of interventions related to a disease process that, when executed together, result in a better outcome than when implemented separately (Fulbrook & Mooney 2003).

Meeting the physical needs of the critically ill patient

Respiratory needs and care

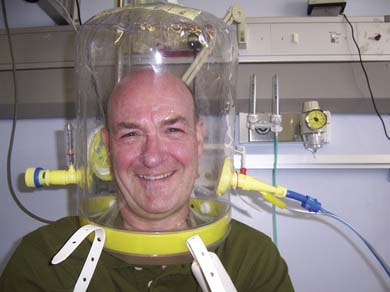

Many disease processes may lead to the need for ventilatory support (Box 29.2). Mechanical ventilation is the artificial support of, or assistance with, breathing when adequate gaseous exchange and tissue perfusion can no longer be maintained (see Ch. 3). Ventilatory support can be administered ‘invasively’ through an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy or non-invasively through a mask or hood. Both methods can maintain vital function; the type of support required depends on the patient’s underlying condition. Patients with type I or type II respiratory failure or acute pulmonary oedema are likely to have a good response to non-invasive ventilation, which may avoid intubation (Tully 2002).

Box 29.2 Information

(adapted from Weilitz 1993)

Ventilation modes

Invasive modes

The potential complications of mechanical ventilation are outlined in Box 29.3.

Non-invasive modes

This mode is frequently employed in type II respiratory failure or as a maximum treatment option if the patient is not suitable for invasive ventilation (British Thoracic Society 2002).

Non-invasive ventilation has become a popular choice for clinicians in recent years. It has the potential advantage over invasive methods of reducing the risk of infection and reducing length of stay (Tully 2002).

Monitoring respiratory function and maintaining safe ventilation

Monitoring and maintaining safe ventilation is crucial and, once the patient is intubated (see Ch. 28) and receiving ventilation support, constant and thorough observations are required as there are many associated complications (see Box 29.3).

Ventilator associated pneumonia

A ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) can be defined as a nosocomial airway infection that develops more than 48 hours after intubation (Westwell 2008). There is good evidence that implementing a ventilator care bundle can demonstrate a significant reduction of VAP (Arlene et al 2007).

Ventilator care bundle

The following components should be incorporated into the patient’s daily care.

Each bundle element has its own set of exclusion criteria. Further information can be found on the Scottish Intensive Care Society website (www.sicsag.org.nhs.uk). An aide-memoire of the bundle is included on the website.

Endotracheal cuff pressures

These need to be checked regularly using an endotracheal cuff manometer. While cuff pressures of 30 mmHg are recommended, pressures of 17–23 mmHg have been shown to be adequate. Complications arising from prolonged excessive ET cuff pressures include tracheal oedema, loss of mucosal cilia, ulceration, ruptured tracheo-oesophageal fistula, stenosis, necrosis, sore throat and hoarseness (Wood 1998). Prevention of these complications is the reason why a tracheostomy is recommended after 12–14 days of oral intubation.

Ventilator observations

Continual observation of the patient should include:

Observations of the ventilator should include:

Arterial blood gases (ABGs)

Judicious analysis of ABGs (see Ch. 3) will most accurately reveal a patient’s respiratory progress or deterioration and the adequacy of ventilatory support. Care must be taken not to oversample, to prevent iatrogenic anemia (Andrews & Waterman 2008).

Inhaled nitric oxide (NO) administration

The administration of inhaled nitric oxide can improve oxygenation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Whilst there is good evidence of improvement of oxygenation in the short term (Hsu et al 2008) the treatment shows no mortality benefit. Nitric oxide is a highly toxic environmental pollutant and so closed suction systems should always be used.

Positioning

When a patient’s oxygenation remains poor, despite high oxygen delivery and high PEEP levels (classically found in ALI), it may be decided to position the patient face down in the prone position. This manoeuvre increases lung compliance by recruiting underventilated areas of the posterior lung bases and improves oxygenation (Mancebo et al 2006).

Endotracheal suction

Together with hand ventilation (see below), ET suctioning is a procedure used to facilitate the clearance of secretions when a patient’s normal cough mechanism is either inadequate or disrupted. This may occur where there is underlying respiratory or neurological disease or where the cough reflex is suppressed by sedation, muscle relaxants or anaesthetic agents during IPPV. Its purpose is the removal of pulmonary secretions, to avoid the problems associated with their retention, such as increased airway pressures, pneumothorax, cardiovascular instability, lobar consolidation, ventilation–perfusion mismatch, pneumonia, hypoxaemia and atelectasis. However, endotracheal suction can produce complications and carries with it hidden risks (see Box 29.4). Maintaining a patent airway involves endotracheal suctioning and, while it is essential to keep the airway clear of secretions, it is also important not to oversuction and thereby cause unnecessary trauma, irritation and hypoxia (Wood 1998). In order to minimise these risks certain principles should be adhered to; these are discussed in Chapter 28.

Hand ventilation (manual hyperinflation)

Manual hyperinflation is a manual form of positive pressure ventilation using a rebreathing bag. It is used primarily to stimulate a cough in patients with either a poor or absent cough reflex, or when there is atelectasis or excessive bronchial secretions. This intervention must be carefully assessed on an individual patient basis as it is not without severe adverse effects (see Box 29.5) and may have a negative effect on patients with raised intracranial pressure. Hand ventilation may be necessary when there is a ventilator fault, or during cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Weaning

Weaning is the term used to describe the gradual transition from mechanical to spontaneous ventilation (self-ventilation). During the weaning phase, patients may alternate between these modes until they are able to cope continually on a reduced mode, ultimately achieving spontaneous breathing. It should be individually tailored and begun as soon as it is established that the patient is physically capable of maintaining respiration. The nurse has a key role to play in this. Patients who are likely to require ventilation over a longer period of time will be considered for a tracheostomy (see Chapter 14), which is more comfortable and the patient will require less sedation. It is good practice to allow the patient to rest overnight by giving them increased ventilatory support, which will also allow the patient’s PaCO2 to return to normal. Each patient should be assessed for readiness to wean each day, an example of an assessment tool can be found on the web.

Cardiovascular care

In critical care settings, monitoring systems are essential in order to evaluate any potentially fatal physiological derangements and to allow timely treatment to correct any abnormalities. The cardiovascular system can be monitored by the measurement of volume, flow, pressure and resistance in different areas. Chapter 2 covers haemodynamic aspects of care and should be referred to in relation to this section. Patients admitted to critical care units undergo monitoring to glean information about tissue perfusion, blood volume, tissue oxygenation and vascular tone. It is the nurse’s responsibility to carefully monitor these parameters and identify changes.

Nursing management and health promotion: cardiovascular care

Monitoring heart rate and rhythm

The amount of information that can be gleaned from a three-lead ECG and, more importantly, a 12-lead ECG, must never be underestimated and a sound understanding of the heart’s electrical activity facilitates this (see Ch. 2). Cardiac arrhythmias are commonplace in patients in critical care. Hypoxia, shock, electrolyte abnormalities, sepsis, vagal stimulation from ET suctioning, irritation from central venous or pulmonary artery catheters, and medication are responsible for the majority of cardiac arrhythmias; however, some will be the result of myocardial ischaemia in patients with underlying heart disease. Accordingly, where possible, the nurse needs to be aware of any cardiac impairment the patient may have. Monitoring should be continuous, to enable early detection and prompt treatment of underlying problems. For information about the conduction pathways of the heart, arrhythmias and their management, see Chapter 2.

Monitoring arterial blood pressure

Critically ill patients generally have an arterial line inserted for the accurate measurement of arterial blood pressure and the provision of easy access to arterial blood for blood gas analysis. Common sites for the insertion of arterial lines are (in order of preference): radial artery, brachial artery, femoral artery, dorsalis pedis artery (see Ch. 18 for care of patients with arterial lines). Together with the systolic and diastolic arterial pressure, the mean arterial pressure (MAP) is also recorded. This gives the measurement of perfusion pressure over the majority of the cardiac cycle. A MAP of 65–85 mmHg is generally the acceptable range. Below 50 mmHg is dangerous as it is inadequate to perfuse vital organs and tissues. Complications associated with arterial lines can and do arise (Box 29.6).

Box 29.6 Information

Complications associated with arterial lines

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree