CHAPTER 3 Nursing patients with respiratory disorders

Introduction

The respiratory system is one of the most vital systems in the human body. In health, it functions automatically and usually without our awareness. However, there are several diseases, both acute and chronic, which have a disruptive effect on the respiratory system. The most common causes of respiratory disease are related to smoking, infection, allergens, genetics and poverty. Respiratory disease affects approximately 8 million people in the UK, resulting in one in five people dying of respiratory disease. The burden of respiratory disease on the National Health Service (NHS) is steadily increasing. It is the single most common reason why people consult their general practitioner (GP) and accounts for over a million bed days a year in England (British Thoracic Society 2006a). The impact on the individual is more difficult to measure, although it has been recognised that disability is a frequent consequence of respiratory impairment.

Anatomy and physiology – overview

This section is intended as an overview of the most relevant points relating to normal respiratory function. For a more detailed discussion please consult a biology text book such as Ross and Wilson (Waugh & Grant 2006).

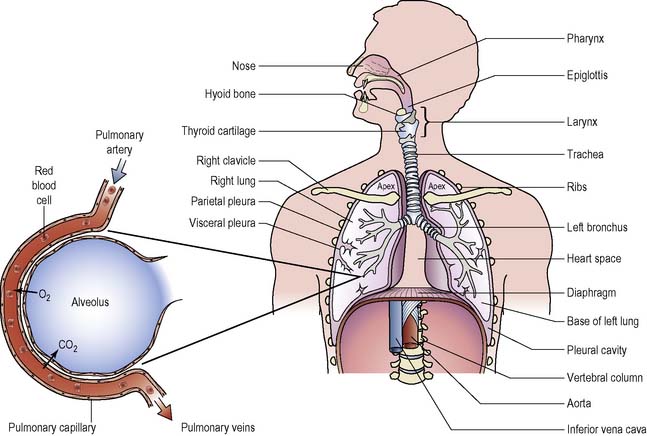

The respiratory system comprises the upper and lower airways and the thoracic cage (Figure 3.1).

Pulmonary function

Lung volume capacity and compliance

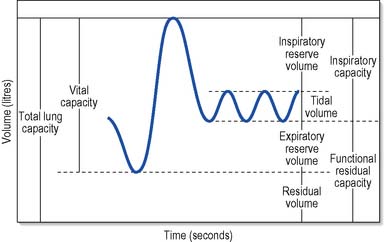

The volume of air breathed in and out and the number of breaths per minute vary from one individual to another according to age, size and activity. Normal, quiet breathing gives about 15 complete cycles per minute in the adult. Lung volume can be assessed in the following terms (Figure 3.2):

Principles of nursing management in the prevention and treatment of respiratory disorders

There are two main nursing priorities:

Health promotion and disease prevention

Promoting health and preventing disease are vital to the social and economic well-being of our society and their importance is reflected in government legislation and the development of large-scale screening and health education programmes (Donaldson et al 2005). With the cost of health care soaring, it makes good sense to prevent disease where possible rather than just treating the consequences.

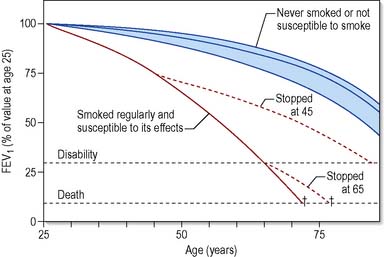

Fletcher & Peto (1977) demonstrated that smoking accelerates the normal decline in lung function due to the ageing process from about 30 mL per year to 45 mL per year (Figure 3.3). The consequence of this increased loss of lung function is that functional impairment occurs leading to fatigue and breathlessness which impacts on the individual’s ability to perform normal activities of daily living (ADL). Furthermore, smoking in pregnancy leads to an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, premature birth, smaller babies and sudden infant death syndrome. Children who are subject to passive smoking from parental smoking are more likely to experience acute respiratory illness, chronic middle ear infection, asthma, chronic cough and wheezy chest.

Figure 3.3 The effects of smoking on the decline in lung function.

(Reproduced from Fletcher and Peto 1977 with permission.)

Nurses are well placed in their many roles in the hospital and community to have an active and expanding role in the area of primary health prevention through health promotion activities in relation to tobacco control (Buck 1997).

Smoking cessation

Of the 13 million smokers in the UK, over 68% (General Household Survey – Office for National Statistics 2005) say they want to stop and this has often been directly related to specific reasons, for example a life event, health reasons, social pressure or financial reasons. Of this 60%, only half intend to stop in the next year, only a third of these make an attempt and only 2% succeed on their own. Stopping smoking requires motivation, effort, commitment and stamina to be successful, therefore it has to be the right time for the smoker to make an attempt. Helping people to stop smoking is a challenge faced by many nurses as it requires facilitating change and supporting patients through the process rather than actively providing care. Behaviour change required for smoking cessation is complex, with nicotine addiction as well as many other factors including social and psychological influences playing their part. Evidence-based smoking cessation guidelines have been developed to assist health care professionals to develop smoking cessation strategies that fit in with the overall tobacco control (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE] 2006a, 2008a, West et al 2000).

This approach is supported by NICE (2002, 2008b) and it will ensure that patients are referred to smoking cessation services, often run by practice nurses or specially trained smoking cessation advisors. There are two main strategies used in smoking cessation: pharmacological interventions and lifestyle behavioural change.

Pharmacological interventions

The use of pharmacological agents has been shown to double the chances of success of smokers wishing to quit (West et al 2000) and, provided they are used in sufficient quantity and for a long enough period of time, to reduce the withdrawal symptoms as outlined in Table 3.1.

| Symptoms | Duration | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Irritability/aggression (nicotine withdrawal) | − 4 wks | 50% |

| Depression | − 4 wks | 60% |

| Restlessness | − 4 wks | 60% |

| Poor concentration | − 2 wks | 60% |

| Cough (clearing lungs out) | − 2 wks | 60% |

| Increased appetite (food tastes better) | + 10 wks | 70% |

| Light headedness (more oxygen to brain) | − 48 h | 10% |

| Night-time awakenings | – 1 wk | 25% |

| Urges to smoke | + 2 wks | 70% |

| Anxiety | – 1 wk | 50% |

– 4 wks, in the first 4 weeks; + 10 wks, after 10 weeks.

Lifestyle behavioural change

Smoking is a complex habit and dealing with the nicotine withdrawal alone may not be sufficient to quit smoking. Emphasis needs to be placed on the psychological and social aspects of the habit as well as the management of the nicotine withdrawal symptoms if smoking cessation is to be achieved. The most commonly used approach to behavioural change for smoking cessation is based on the Prochaska & DiClemente (1984) model of change, which assumes that the individual attempting to change behaviour will follow a series of five stages:

Being able to assess a person’s stage of change will allow the nurse to use appropriate strategies to help the individual to quit the habit of smoking. Furthermore, helping smokers to understand the effects of smoking on the body and how stopping smoking can improve health can motivate the smoker to quit. Table 3.2 demonstrates the withdrawal effects which Hatsukami et al (1984) showed were of rapid onset following stopping smoking.

Table 3.2 The effects once you give up smoking begin as soon as the cigarette is stubbed out

| Short term (7–14 days) |

|---|

| Nicotine levels in the blood begin to fall 20 minutes Stimulation of adrenaline and noradrenaline ceases and blood pressure and heart rate return to normal 2 hours Nicotine levels continue to fall in the blood 8 hours Carbon monoxide and nicotine levels in the blood are reduced by half Oxygen levels return to normal 24 hours Carbon monoxide will be eliminated from the body A CO reading will be at normal levels 3–4 days Smooth muscle in the bronchioles begins to relax Breathing improves Energy levels increase 5–14 days Mucus glands no longer being over-stimulated Mucus clearance begins |

| Medium term (2–12 weeks) |

|---|

| Circulation, sense of smell and taste improve 3–9 months Respiratory symptoms improve Nasal congestion, cough and sputum production reduce 12 months Risk of small cell lung cancer halved Lung function cannot be reversed after years of damage; however, stopping smoking means that the rate of decline reverts to the age decline of a non-smoker (30 mL per year) and prevents further damage. The reduction in mucus production helps to reduce exacerbations |

Respiratory assessment and investigations

Nursing assessment of respiratory status

Oxygen levels

Observation of skin colour and pulse oximetry (oxygen saturation) will indicate whether the patient is receiving adequate oxygenation. The patient’s skin should be observed for blueness of the lips, tongue and oral mucosa, as this indicates the presence of central cyanosis caused by hypoxaemia (low oxygen levels in arterial blood). In patients with dark skin it may not be possible to see changes in lip colour and therefore the oral mucosa and tongue should always be examined. Hypoxaemia will also be detected through performing pulse oximetry as this will measure oxygen saturation levels. According to the British Thoracic Society (2008) the normal ranges are:

Impact on activities of daily living

Assessing the impact of breathlessness on all the activities of daily living will allow the nurse to plan care effectively, identifying the need for referral to occupational therapy, physiotherapy, dietetics and social services as appropriate. Particular attention to mobility and nutritional status is essential, as breathlessness has been shown to cause immobility, and malnutrition due to increased energy requirements and poor appetite (Margereson & Esmond 1997). Patients with underlying respiratory disease should be observed for increasing breathlessness and oxygen desaturation (lowering of oxygen levels) on exertion, as this may indicate the need for supplementary oxygen to prevent complications of immobility. Assessment of the patient’s nutritional status should include body mass index (BMI, see Ch. 21), identification of recent significant weight loss, eating habits and changes in appetite. Patients found to have a BMI less than 20 or those with a recent weight loss greater than 10% should be referred to a dietitian.

Respiratory investigations

Lung function tests

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

) is the volume of gas that reaches the alveoli per minute and is approximately 4 L/min. The perfusion (

) is the volume of gas that reaches the alveoli per minute and is approximately 4 L/min. The perfusion ( ) is the amount of blood that flows through the pulmonary capillaries per minute and is approximately 5 L/min. The normal

) is the amount of blood that flows through the pulmonary capillaries per minute and is approximately 5 L/min. The normal  ratio is

ratio is  minus

minus  which is 0.8, although this will change in various parts of the lung due to gravitational forces. In healthy individuals these gravitational differences do not affect adequate gaseous exchange; however, in lung disease the mismatch is wider and is the most common cause of low oxygen levels in arterial blood (hypoxaemia). With effective ventilation and perfusion, oxygen is able to diffuse from the alveoli into the blood to achieve a partial pressure (PaO2) of between 10 and 13 kPa.

which is 0.8, although this will change in various parts of the lung due to gravitational forces. In healthy individuals these gravitational differences do not affect adequate gaseous exchange; however, in lung disease the mismatch is wider and is the most common cause of low oxygen levels in arterial blood (hypoxaemia). With effective ventilation and perfusion, oxygen is able to diffuse from the alveoli into the blood to achieve a partial pressure (PaO2) of between 10 and 13 kPa.