CHAPTER 4 Nursing patients with gastrointestinal, liver and biliary disorders

Introduction

As gastrointestinal disorders continue to be the number one complaint requiring medical attention in a variety of settings, anatomical and physiological knowledge of the gastrointestinal (GI) system is essential for nursing practice. In 2007 Dinsdale reported that deaths from diseases of the GI system had increased by 25% over the previous ten years (Dinsdale 2007). Therefore, as the demand for medical care rises there is an increased need for knowledgeable and competent nurses to assess, plan, implement and evaluate the sometimes complex and challenging nursing care patients require.

This chapter begins with an overview of the basic anatomy and physiology of the GI tract and related structures, describing the basic functions of the system and how the specialised organs and tissues contribute to effective functioning. Readers are encouraged to read Waugh & Grant (2006) Chapter 12 for a more in-depth discussion of the anatomy and physiology of the GI system. The disorders of the GI system, liver and biliary tract most commonly encountered by nurses in hospital or community settings are described and the essential nursing care these patients require is detailed. Nursing patients with disorders of the mouth and its related structures is addressed in a separate chapter (Ch. 15).

Anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal tract

The mouth

The mouth has three functions in the process of digestion: mastication (the mechanical chewing of food), salivation (moistening of the food) and deglutition (swallowing of the food) (see Ch. 15 and Figure 15.1).

The tongue, composed mainly of skeletal muscle covered with mucous membrane, manoeuvres and shapes food within the mouth for swallowing. The tongue is also a sensory organ, allowing the taste, texture and temperature of food and fluids to be perceived. The upper surface of the tongue is covered with filiform papillae or taste buds, housing the relevant sensory nerve endings (Drake et al 2005).

Saliva, composed of 99.5% water and 0.5% solutes, is released from three pairs of glands: the parotid, the submandibular and the sublingual glands located outside the mouth around the lower jaw. The submandibular glands secrete about 70% of saliva in the absence of a food stimulus to keep the mucous membranes moist and lubricate the tongue and lips during speech. However, the sight, smell or presence of food in the mouth will stimulate the parotid glands also to secrete saliva. In digestion, saliva helps to lubricate food prior to swallowing and also initiates the digestion of starch (Waugh & Grant 2006).

Swallowing

There are three stages of swallowing or deglutition. After food has been sufficiently chewed, it is formed into a bolus between the palate and the tongue. The tongue rolls the bolus and pushes it into the pharynx. This is a voluntary reaction and known as the buccal stage of swallowing. The bolus then passes over the glottis at the entrance of the larynx and trachea. When swallowing occurs a small flap of cartilage, the epiglottis, covers the glottis. This stage of swallowing is referred to as the pharyngeal stage and is involuntary. Once the bolus has passed safely over the epiglottis and involuntarily entered the oesophagus, this stage of swallowing is known as the oesophageal stage of swallowing (Waugh & Grant 2006). For more information see Chapter 15.

The oesophagus

The propulsion of food towards the stomach is achieved by peristalsis, a series of relaxations and contractions of the muscles that force the bolus along the oesophagus. Peristalsis is brought about by waves of contraction of the circular muscle, narrowing the lumen and thereby compressing the bolus of food. This action is preceded by a contraction of the longitudinal muscles to widen the lumen in order to receive the bolus of food. Peristalsis is entirely under involuntary control. Relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter allows food to enter the stomach (Drake et al 2005).

The stomach

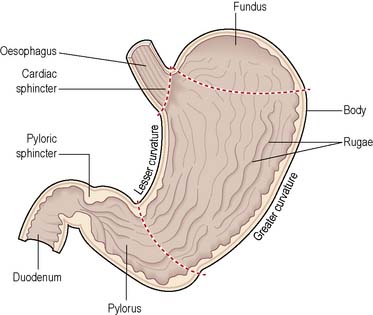

The stomach is a J-shaped enlargement of the GI tract connecting the oesophagus to the duodenum (Norton et al 2008). It is made up of four parts: cardia, fundus, body and pylorus (including the pyloric antrum and pyloric canal). Between the pyloris and the duodenum is the pyloric sphincter. The stomach wall is composed of four layers, similar to the remainder of the GI tract: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis and serosa. The basic structure of the stomach is illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Longitudinal section of the stomach.

(Reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006.)

Digestion continues in the stomach when the bolus of food enters through the lower oesophageal sphincter. On the inner surface of the stomach, the mucosal layer of tissue is supplied with blood vessels and lymph glands by the underlying submucosal layer. Between the mucosal layer and the outermost peritoneal layer lies a muscular layer that is composed of three layers: an inner layer of oblique fibres, a middle layer of circular fibres and an outer layer of longitudinal fibres. These layers of muscle allow increasingly stronger waves of contraction in three directions to mix the food in the stomach and allow maximal contact with gastric juice. Innervation of the stomach is from a branch of cranial nerve X (vagus) providing parasympathetic nerve endings that stimulate the secretory cells of the stomach. The internal surface area of the stomach is increased by the arrangement of rugae in the lining (Waugh & Grant 2006).

Gastric juice

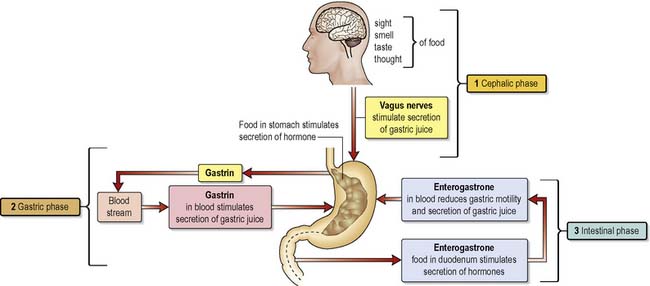

Release of gastric juice by the stomach mucosa is stimulated by the sight, smell and thought of food, referred to as the cephalic phase of digestion. The gastric phase of digestion begins when food reaches the stomach and continues until chyme enters the duodenum where the intestinal phase of gastric digestion begins. The length of time taken to empty the stomach is variable and depends on the composition of the meal eaten. The average time for emptying of the stomach after a meal is about 4 h. Emptying takes place through the pylorus. The pyloric region holds about 30 mL of chyme; with each wave of contraction in the stomach about 3 mL of chyme is released into the duodenum. This process is regulated by the pyloric sphincter (Waugh & Grant 2006).

Digestion

The intestinal phase of digestion begins when chyme enters the duodenum. The main effect on gastric digestion of the entry of food into the duodenum is inhibitory. The enterogastric reflex, mediated via the medulla, leads to the inhibition of gastric secretion. Enterogastrone relates to any hormone secreted by the mucosa of the duodenum that inhibits the forward movement of the contents of chyme. The enterogastric reflex is one of the three extrinsic reflexes of the gastrointestinal tract. When it is stimulated the release of the hormone ‘gastrin’ from the G-cells in the antrum of the stomach is inhibited, thereby further inhibiting gastric motility and secretion of gastric acid. In addition, the presence of food in the duodenum stimulates the release of three hormones, namely secretin, cholecystokinin and gastric inhibitory peptide, all of which inhibit gastric juice secretion and reduce gastric motility (Figure 4.2).

The small intestine

Extending from the pyloric sphincter to the ileocaecal valve, the small intestine is responsible for the completion of digestion, the absorption of nutrients and the reabsorption of most of the water that enters the digestive tract. The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine and is approximately 25 cm in length. Secretions from the gall bladder and the pancreas are mixed with chyme and enter the duodenum through the ampulla of Vater, the joining of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct. The emptying of the gall bladder is regulated by the sphincter of Oddi (Waugh & Grant 2006).

The duodenum

In common with the remainder of the small intestine, the duodenum has a mucosal layer, a submucosal layer, a muscular layer and a peritoneal layer (Drake et al 2005). However, unlike the remainder of the small intestine, the duodenum is relatively immobile. Its regulatory role is fulfilled when the stimulus of chyme entering the duodenum triggers the enterogastric reflex as well as stimulating the release of gastrin, secretin, cholecystokinin and gastric inhibitory peptide. Secretin also stimulates the cells of the liver to secrete bile, and cholecystokinin stimulates the release of digestive enzymes by the small intestine.

Chyme is very acidic (with a pH of about 2) because of its high concentration of hydrochloric acid. When chyme enters the duodenum it becomes neutralised by the effect of alkaline bicarbonate released by the pancreas. The bile emulsifies fats in the chyme, breaking up fat globules into smaller particles. The enzymes of pancreatic juice can then begin to digest respective food substances in the duodenum. This action is continued as the chyme is passed down the small intestine (Waugh & Grant 2006).

The jejunum and ileum

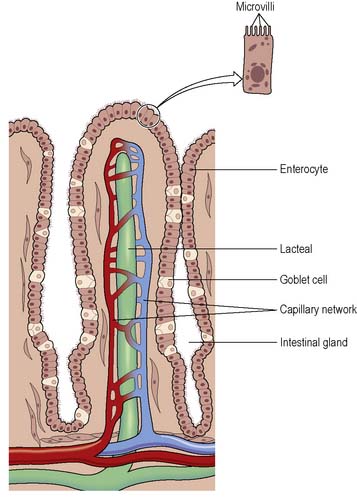

The first two fifths of the small intestine after the duodenum is the jejunum, and the remaining three fifths, the ileum. Two types of movement, known as segmentation and peristalsis, mix and move food along the small intestine. Secretory cells of the mucosa of the small intestine release a slightly alkaline juice containing mainly water and mucus. The remaining enzymes of digestion in the GI tract are located on the microvilli, microscopic finger-like projections of the cell membrane. The enzymes of the small intestine complete the digestion of all components of the diet, including protein, fat, carbohydrate and nucleic acids (Norton et al 2008).

Absorption of nutrients

Absorption takes place along the full length of the small intestine and 90% of all the products of digestion are absorbed here. The products of digestion are amino acids and peptides from protein, fatty acids and monoglycerides from fats, hexose sugars from carbohydrates, and pentose sugars and nitrogen-containing bases from nucleic acids. About 7.5 litres of water are secreted into the small intestine daily and 1.5 litres ingested. As only about 1 litre enters the large intestine, the major portion of the water is reabsorbed in the small intestine. Absorption occurs by two main processes: diffusion and active transport. Absorption takes place at the villi. Each villus contains an arteriole and a venule connected by a capillary network, and a central lacteal, a projection of the lymphatic system (Figure 4.3). Short-chain fatty acids, amino acids and carbohydrates are absorbed directly into the bloodstream. Triglycerides form structures called chylomicrons, which are also absorbed into the lacteals and then enter the bloodstream where the thoracic lymphatic duct empties into the left subclavian vein. Monosaccharides, amino acids, fatty acids and glycerol are actively transported into the villi. Disaccharides, dipeptides and tripeptides are also actively transported into the enterocytes and digestion is completed before transfer into the capillaries of the villi (Waugh & Grant 2006).

The large intestine

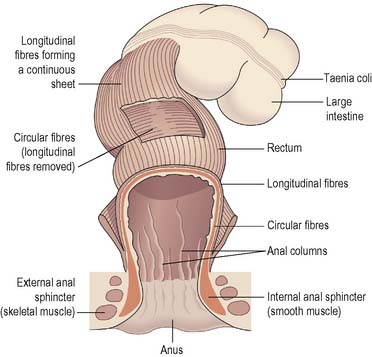

The large intestine is divided into four portions: the ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon. The curves joining the ascending with the transverse colon and the transverse with the descending colon are referred to as the hepatic and splenic flexures respectively. Two features can be identified near the ileocaecal valve: the caecum, a pouch below the ileocaecal valve, and the appendix, a finger-like projection of the caecum. The descending colon leads to the sigmoid colon, terminating in the rectum. Three muscular bands called the taeniae coli run the length of the large intestine. These maintain a slight longitudinal tension in the large intestine and give the colon its characteristic segmented appearance. The rectum stores food residue as faeces before expulsion via the anus. The anal canal opens externally at the anus, controls evacuation and has an internal anal sphincter of smooth muscle and an external anal sphincter of skeletal muscle (Drake et al 2005).

Defaecation

When faeces reach the rectum, a reflex is initiated whereby stretch receptors in the wall of the rectum send signals to the brain informing it of the presence of faeces. However, defaecation can be suppressed until the time and place are appropriate. When it is appropriate to defaecate, the internal anal sphincter automatically relaxes and the external anal sphincter, under voluntary control, is relaxed. Intra-abdominal pressure is increased as the individual breathes in and holds the breath against a closed glottis (Valsalva’s manoeuvre), and faeces are expelled from the rectum via the anal canal (Waugh & Grant 2006) (Figure 4.4).

Disorders of the gastrointestinal tract

Disorders of the mouth

The principles of mouth care and the treatment of a range of disorders affecting the mouth and related structures are described in detail in Chapter 15. For further reading on oral care, see Nicol et al (2008).

Disorders of the oesophagus

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is an increasingly prevalent condition where the reflux of the contents of stomach causes troublesome symptoms that can have a significant impact on the physical, social and emotional life quality of those living with it (Box 4.1). The prevalence of GORD worldwide is estimated to be between 5 and 20% with the highest incidence being found in Europe and the USA (van Baalen 2008).

Box 4.1 Information

Although there is considerable variation in the severity and frequency of symptoms, and less than half of those who have endoscopy show evidence of oesophageal injury, prolonged and severe reflux can lead to erosive oesophagitis, oesophageal ulcer, peptic stricture, haemorrhage, Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus (CLO) (Box 4.2) and a predisposition to malignant changes and the development of oesophageal cancer (Morcom 2008).

Box 4.2 Information

Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus (CLO)

Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus (CLO) is generally accepted to be a pre-malignant condition for oesophageal adenocarcinoma and has been defined as ‘an oesophagus in which any portion of the normal squamous lining has been replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium which is visible macroscopically’ (British Society of Gastroenterology 2005.

Pathophysiology and risk factors

Normally, the action of swallowing stimulates the relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), which permits the passage of food into the stomach. In GORD, however, there is prolonged or inappropriate relaxation of the LOS, which results in reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus. Fox & Forgacs (2006) suggest that those with mild to moderate GORD do not necessarily have more transient LOS relaxations but structural changes at the gastro-oesophageal junction reduce the resistance to reflux during these events. Therefore, as structural changes become more marked the risk of reflux rises and the reflux volume increases, extending further up the oesophagus. As the stomach is highly acidic with a pH of 1–4, regurgitation of contents is abrasive to the oesophageal lining resulting in the characteristic symptoms of GORD.

Hiatus hernia

In those with severe GORD symptoms, a hiatus hernia, which is a condition whereby a portion of the stomach protrudes upwards into the chest through an opening in the diaphragm, is often present (Fox & Forgacs 2006). In this condition, a large amount of gastric contents pass unhindered into the hiatal sac with ensuing severe symptoms. Hiatus hernias occur most frequently from middle age onwards. They are four times more common in women than in men and are often found in association with obesity. However, they can also result from a congenital abnormality presenting in early infancy. Hiatus hernias are described as ‘sliding’ or ‘rolling’ (para-oesophageal), the former being the more common. In sliding hernias, the oesophageal sphincter mechanism is defective, causing reflux of acid-peptic stomach contents and, as their name suggests, the herniated stomach tends to slide back and forth into and out of the chest. In the less common ‘rolling’ or para-oesophageal hernia, the gastro-oesophageal junction remains where it belongs but part of the stomach is squeezed up beside the oesophagus. These hernias remain in the chest at all times.

Although the primary cause of GORD is the compromised functioning of the LOS, genetic, environmental, behavioural and co-morbid risk factors are thought to be associated with the development of the condition (Dent et al 2005). Whilst lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption and drugs that impair sphincter pressure (anticholinergics, theophylline, nitrates, calcium channel blockers, progestogens, nicotine replacement therapy) do not cause GORD, they can worsen the symptoms. Obesity has also been associated with GORD, particularly where there is a tendency to consume larger meals and rich, energy-dense foods, which increase the risk of reflux. Although Dent et al (2005) found no clear association between certain foods and GORD, some patients report that fatty foods, citrus fruits, coffee, chocolate, etc. may trigger an episode and therefore they avoid them (Fox & Forgacs 2006). Reflux is also very common in pregnancy due to the effect of progesterone in relaxing the gastro-oesophageal sphincter smooth muscle and also the increased pressure on the stomach as the fetus grows.

Diagnosis

Traditionally, diagnosis of GORD focused on the notion of a continuous spectrum of disease and the presence of objective evidence of reflux and injury to the oesophagus (Fox & Forgacs 2006, Morcom 2008). For example, absence of oesophageal injury was associated with mild disease whilst Barrett’s CLO was classified as a severe form of GORD. However, recent evidence suggests that this idea of progression from mild to severe disease is rarely seen and the new conception of GORD has its basis in a global definition that focuses on symptoms rather than injury. What this means is that while heartburn and regurgitation constitute the cardinal symptoms of GORD, evidence of oesophageal injury is not necessary to confirm a diagnosis. What is considered important is that treatment and management options are based on patients’ reports of symptoms and the impact on their lives.

A significant outcome of this change is that pharmacological and lifestyle management are the first line of treatment and routine endoscopic investigation is not considered necessary for those who do not present with ‘alarm’ symptoms. However, urgent referral for endoscopic investigation is recommended (Box 4.3) in cases where alarm features are present. These include gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia, unexplained and unintentional weight loss, progressive dysphagia, persistent vomiting, palpable epigastric mass, a family history of gastrointestinal cancer, previous documented peptic ulcer or suspicious imaging results (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE] 2005a).

Box 4.3 Information

Endoscopy in GI medicine

Endoscopy refers to the visualisation of the interior of the body cavities and hollow organs by means of a flexible fibreoptic instrument (endoscope). The use of this technique has contributed greatly to diagnosis and therapy in many areas of medical practice. For use in the gastrointestinal tract, the endoscope is variously designed to view the oesophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, the colon and the rectum. It is also possible, by a modification of the gastroduodenoscope, to visualise the pancreatic and common bile duct; this is called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Although most endoscopes are flexible, a rigid instrument may be used for a sigmoidoscopy. For further information see Cotton & Ackerman (2003).

Treatment options

Lifestyle modifications alone are not considered effective for the relief of GORD symptoms and are generally recommended as an adjunct to pharmacological therapy, which is the mainstay of non-surgical intervention. Nonetheless, based on the assumption that certain factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption and obesity can contribute to frequency and severity of symptoms, modifications are often recommended. Dietary adjustments such as avoiding alcohol and foods that appear to trigger symptoms are strategies adopted by patients. Avoiding large meals and eating several hours before going to bed is suggested. For those who are overweight or obese, weight loss can be effective in ameliorating symptoms, and elevating the head of the bed is also helpful for some (Morcom 2008). Smoking cessation is advised (Box 4.4).

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological intervention forms the mainstay of treatment.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

Those with reflux symptoms are given initial treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for one month. PPIs (e.g. omeprazole, lansoprazole) are effective acid suppressants and heal reflux oesophagitis in many patients. There is a high rate of symptom recurrence in GORD when PPIs are discontinued, and when this happens long-term and maintenance therapy is required (van Baalen 2008). PPIs are considered to be safe and effective and are not associated with the development of abnormal cells or neoplasms (Fox & Forgacs 2006). In a minority of patients where PPI therapy is ineffective, altering the medication and dosage must be undertaken in order to achieve a level of symptom control.

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

Although histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) such as cimetidine and ranitidine also suppress acid, they are seen as less effective than PPIs in healing oesophagitis and maintaining remission from mucosal symptoms and injury (Fox & Forgacs 2006). However, they are sometimes used before bed if GORD symptoms are prominent at night.

Gastroprotective agents

such as alginates and antacids (e.g. Gaviscon, Maalox Plus) are widely used because of their over the counter availability and they provide instant and temporary relief from symptoms. However, their value in symptom relief is extremely limited and they have no effect on the healing of oesophagitis (Morcom 2008).

Surgical interventions

The vast majority of patients with GORD respond to pharmacological therapy and lifestyle adjustments or modifications. However, for a minority they are ineffective and surgery is an option that offers a permanent resolution for symptoms. Surgery is also recommended for those who have volume reflux, respiratory symptoms (e.g. cough/asthma) and Barrett’s CLO. Before surgery is considered, however, diagnostic investigations include visual assessment of the oesophagus (gastroscopy) in order to determine whether there is evidence of physical damage (oesophagitis, hiatus hernia, Barrett’s CLO). In addition, 24-h oesophageal manometry and motility studies may be performed to establish the extent of the acid reflux and the severity of the disease and to identify those best suited to surgery (van Baalen 2008).

The purpose of anti-reflux surgery is to recreate the LOS and surgery is commonly performed laparoscopically as this enables a more rapid recovery and reduced hospital stay. It is also associated with reduced pain as there is no abdominal or chest incision and improved respiratory function postoperatively (van Baalen 2008). Essentially, laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery (LARS) mobilises the lower end of the oesophagus, reduces the oesophageal hiatus using sutures, and wraps the fundus of the stomach partially or completely around it (fundoplication).

Nursing management and health promotion: GORD

Pre-operative management

Preparation for LARS surgery will be as for elective abdominal surgery on the GI tract as described in Chapter 26 (see p. 695). In addition, the patient must be given information about the surgery and the risks associated with it. The short- and long-term effects of the surgery and the changes in diet that are required should be explained in sufficient detail so that the patient has a clear understanding of the implications and is making an informed choice to undergo the procedure.

Postoperative management

Those who have LARS surgery normally remain in hospital for approximately 48 h post surgery. Nursing management in the postoperative period centres on early detection of and minimising the risk of complications (Box 4.5).

Box 4.5 Information

Complications and side-effects of LARS (van Baalen 2008)

| Complications of LARS | Side-effects of LARS |

|---|---|

| Dysphagia (early and late) Para-oesophageal hernia Gastrointestinal perforation Pneumothorax Pulmonary embolism Injury to major vessels | Inability to belch Early feeling of fullness Bloating Increased flatulence |

Pain assessment and documentation should be undertaken using a pain assessment tool such as the visual analogue scale (see Ch. 19). Opiates are commonly used to control pain and are usually administered intravenously. Should the patient have patient controlled analgesia (PCA), it does not remove the need for evaluation of the effectiveness of pain relief. This should be undertaken at the same time as vital sign monitoring. Sedation level must also be monitored. The patient should also be given antiemetics intravenously as it is important to minimise the risk of nausea and vomiting. The patient remains nil by mouth on the day of surgery, and monitoring for signs of dysphagia is undertaken. To maintain hydration, intravenous fluids are administered. Oral fluids and a liquid diet are normally introduced the day after surgery.

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

The majority of carcinomas of the oesophagus occur in older people with a male to female ratio of 2:1 (Cancer Research UK 2009a). The incidence of oesophageal cancer has increased and according to Cancer Research UK (2009a) it is the ninth most common cancer in the UK. This form of cancer is extremely unpleasant and distressing, with surgery on its own or in conjunction with chemotherapy offering the only possibility of cure. However, the prognosis remains poor and the 5-year survival rate is less than 30%. This has been associated with the late presentation of symptoms in this condition (Cancer Research UK 2009a).

Pathophysiology and risk factors

Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma make up the majority of malignant oesophageal tumours. Globally, squamous cell carcinoma remains the most common, although the incidence of adenocarcinoma has been rising in recent years (Griffin & Dunn 2008). This is thought to be associated with the increase in chronic acid and bile reflux arising from lifestyle factors such as those cited below, which causes dysplasia (abnormal maturation/development of cells) of the epithelium of the oesophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma generally occurs in the middle and upper part of the oesophagus, whilst adenocarcinoma tends to arise in the lower third. The primary tumour can spread locally, up or down the oesophagus, and through its wall to the trachea, bronchi, pleura, aorta and lymph vessels. Distant metastases may occur in the liver and lungs.

Several predisposing factors for oesophageal cancer have been identified:

Diagnosis

Where oesophageal carcinoma is suspected an urgent referral for gastrointestinal endoscopy is recommended (NICE 2005b) Disease staging is undertaken using computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). According to van Baalen (2009), contrast-enhanced spiral CT scanning of the chest and abdomen provides information regarding the location and size of the primary tumour, whether or not it is operable and whether or not metastatic disease exists. If the tumour is deemed to be operable EUS is used to assess and stage the tumour. Bronchoscopy may be performed if the tumour is in the upper zone. This will identify whether the bronchus has been invaded and will have a bearing on treatment and care.

Treatment options

Despite the generally poor prognosis, there are a number of treatment options for those with oesophageal cancer. These include: surgery and chemotherapy; surgery alone; endoscopic resection; chemotherapy; chemoradiotherapy and palliative care. These options depend primarily on the location, histology and spread of the tumour as well as patient characteristics and the existence of co-morbidities. Each patient is carefully assessed as to the extent of the disease before a treatment plan is chosen and commenced. Surgery remains the standard treatment where the tumour is localised or operable. However, chemotherapy is now commonly administered pre-operatively as it has been demonstrated not only to improve outcome in respect of survival but also helps in reducing the tumour size, improving tumour-related symptoms, and improving nutritional status and weight gain (van Baalen 2009). Chemoradiotherapy is administered if the tumour is radiosensitive, i.e. a squamous cell carcinoma. This treatment is usually used for tumours of the upper third of the oesophagus, but is also sometimes used for the relief of pain. For those with inoperable carcinoma of the oesophagus, the focus of palliative treatment is on symptom relief. Malignant dysphagia may be relieved by oesophageal dilatation, endoscopic or open insertion of a stent, or tumour ablation with laser, heat, diathermy or injection of cytotoxic substances (Griffin & Dunn 2008).

Nursing management and health promotion: oesophageal carcinoma

Nursing management will depend on whether treatment is surgical or non-surgical.

Surgical: pre-operative management

In addition to the standard pre-operative preparation for all patients who are undergoing gastrointestinal surgery (see Ch. 26) there are particular considerations that must be attended to in the patient who is to have an oesophagectomy. There are several types of oesophagectomy (Box 4.6), the choice of which is determined by the location and size of the tumour as well as the patient’s age, build and level of fitness to tolerate what is physically demanding surgery. Oesophagectomy is not only procedurally difficult but, as it involves the cardiovascular system, carries with it a significant morbidity (van Baalen 2009). Therefore, thorough physiological assessment and preparation must be undertaken in order to minimise the impact for the patient.

In patients who are experiencing nutritional deficits due to dysphagia, nutritional assessment using a tool such as the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) (Elia 2003) is fundamental and it is essential that any deficiencies are addressed pre-operatively. This can be undertaken by encouraging the patient to sip nutritional supplements or, where deemed necessary, through the use of fine-bore nasogastric tube feeding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree