CHAPTER 7 Nursing patients with disorders of the breast and reproductive systems

Part 1 Nursing patients with disorders of the reproductive systems

Introduction

This part of the chapter explores areas of women’s health, men’s health and infertility.

Anatomy and physiology of the female reproductive system

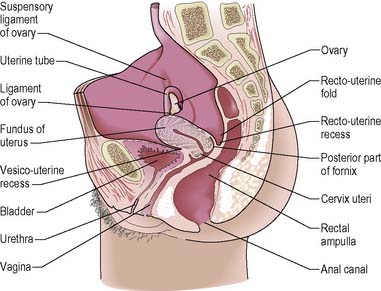

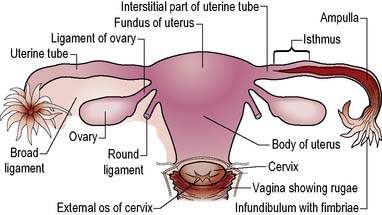

The primary function of the reproductive system is the propagation of the human species. Sexual drive and anticipated pleasure help to meet the reproductive need. The female reproductive system produces gametes (secondary oocytes; strictly speaking these are not known as ova until penetration by a spermatozoon), receives the male penis during sexual intercourse and facilitates the passage of male gametes (spermatozoa). It supports the growth and development of the embryo/fetus during pregnancy and expels the fetus during labour (Figures 7.1, 7.2). See pages 248–249 for anatomy and physiology of the breast. The events occurring at the start of and the end of a female’s reproductive life, the menarche (the first menstruation) and the climacteric and menopause, are outlined.

The female reproductive system consists of:

Ovaries

Oocyte (ovum) production

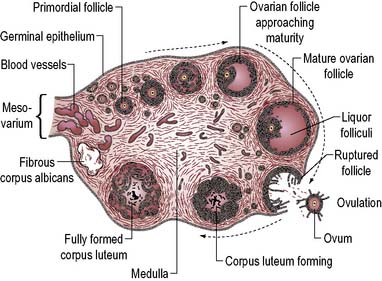

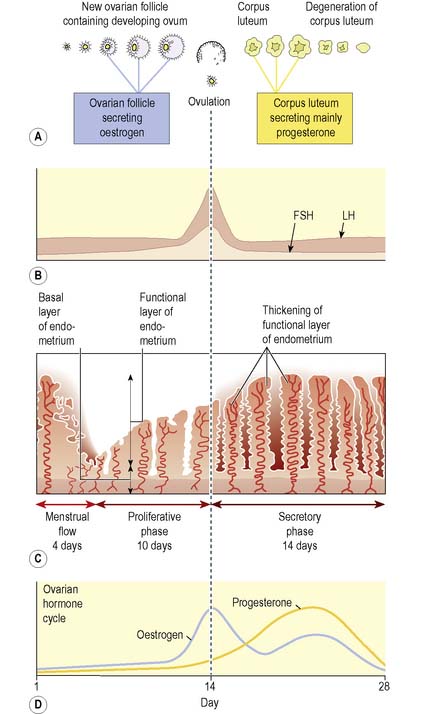

Ovarian cycles begin at puberty; a cycle lasts around 28 days (range 21–35 days) and has two phases follicular (days 1–14) and luteal (days 14–28). Follicles begin to mature under the influence of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH), released by the anterior pituitary gland (see Ch. 5). During the cycle, follicles can pass through five stages (Figure 7.3):

Hormone secretion

Ovarian sex hormone secretion is influenced by hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone, which stimulates the pituitary gland to release FSH and LH (see Ch. 5). FSH stimulates the initial development of ovarian follicles and their secretion of oestrogen; LH stimulates further follicular development, initiates ovulation and stimulates ovarian hormone production. FSH and LH control the secretion of two ovarian steroid hormones – oestrogens and progestogens.

Oestrogens

The effects of oestrogens include:

Uterus

The uterine tubes enter the uterus at its upper outer angles or cornua. The body of the uterus narrows towards the cervix, an area known as the isthmus. The cavity of the uterus connects with the cervical canal at the internal os. The cervical canal opens into the vagina via the external os. The cervix occupies the lower third of the uterus and half of the cervix projects into the vagina. The uterus normally lies in an anteverted position, almost at right angles to the vagina (see Figure 7.1).

Structure

Endometrium

The thickness of the endometrium varies from 0.5 mm just after menstrual flow to about 5 mm near the end of the menstrual (uterine) cycle (see below and p. 197).

Supporting structures

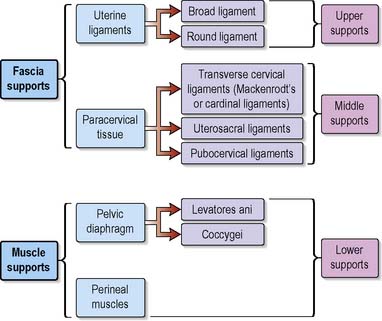

The uterus is maintained in an anteverted and anteflexed position in the pelvis by fascia and muscle structures (Figure 7.4). The uterine ligaments are the:

Functions

The functions of the uterus are:

Menstrual (uterine) cycle

The menstrual (uterine) cycle describes the changes in the endometrium caused by the ovarian hormones (see p. 195). It corresponds to the hormonal events of the ovarian cycle and can be divided into three phases:

Although the menstrual phase occurs at the end of the cycle, by convention the first day of menstruation is counted as day 1 of the cycle, as it provides an observable landmark (Figure 7.5).

Uterine tubes

The uterine tubes (10–14 cm long) turn posteriorly as they extend laterally from the cornua (or horns) of the uterus towards the lateral pelvic wall. The ends open as funnel-shaped structures with fimbriae (finger-like projections) (Figure 7.2). The broad ligament of peritoneum forms the outer serous layer of the tubes. The middle coat, of muscular tissue, is arranged in two layers: an outer longitudinal layer and an inner circular layer. The lining mucosa, comprised mainly of ciliated columnar epithelium and secretory cells, lies in folds. The lumen of the tube is narrow. The ends of the tubes are mobile and at ovulation the fimbriae enfold the adjacent ovary to take up the released oocyte.

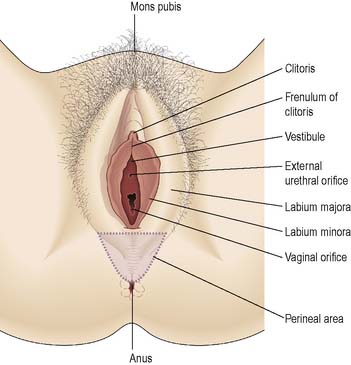

Vagina

The vagina is a fibromuscular channel extending downwards and forwards from the cervix to the labia. The endocervix protrudes into the upper end of the vagina, known as the vault. This creates anterior, posterior and lateral fornices (Figure 7.1). The anterior wall of the vagina is approximately 7.5 cm and the posterior wall about 9 cm in length. The vagina is composed mainly of smooth muscle with a lining mucosa arranged in folds or rugae. Until first sexual intercourse, a fold of mucous membrane, the hymen, forms a border around the external opening of the vagina, partially closing the outlet. Normally the anterior and posterior wallslie in apposition but the vagina is capable of considerable distension during intercourse and childbirth.

Pelvic floor

The pelvic floor is formed by tissues that fill the pelvic outlet and support the pelvic organs.

The climacteric and menopause

A premature menopause is one which occurs before the age of 40 years. This can occur naturally or may be induced iatrogenically. The age of menarche, socioeconomic factors, race, use of oral contraceptives and number of pregnancies appear to have no effect on whether a woman has an early or a late menopause (Abernethy 2005).

Information about the disorders associated with oestrogen withdrawal and hormone replacement is outlined in a later section (see pp. 206–208).

Vasomotor disturbances

Vasomotor disturbances commonly accompany the climacteric. The frequency and intensity of these vary between individuals. Hot flushes/flashes are the most common but perspiration, headache, fainting and palpitations may also be experienced. Hot flushes can start with a sensation of extreme warmth in the chest, quickly followed by flushing of the face and neck. The flush may be accompanied by sweating and palpitations. Dizziness and nausea may also be experienced. Shivering is often reported after the flush, probably due to compensatory constriction of the blood vessels. While vasomotor symptoms will eventually subside with no long-term effects, hot flushes and sweats are embarrassing, uncontrollable and can be distressing for many women. Porter et al (1996) report on a survey of 6096 women aged 45–54 years and note that 84% experienced at least one of the classic symptoms associated with the menopause and 45% of the women reported one or more symptoms as a problem. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have indicated the value of oestrogen in reducing the severity of vasomotor symptoms when compared with placebo.

In addition to oestrogen therapy, other treatments, such as vitamin E and/or B6, clonidine, phytoestrogens, propranolol and oil of evening primrose (contains gamma linoleic acid), have been used. Progestogens have been shown to alleviate hot flushes. Phytoestrogens, found in soya products, have been suggested as a remedy for menopausal symptoms. While some women do find them valuable, there is controversy about advocating them as a therapy for menopausal symptoms (Naftolin & Stanbury 2002).

Menstrual disorders

Amenorrhoea

Pathological amenorrhoea

There are a number of pathological causes of amenorrhoea.

Ovarian lesions

Failure of normal ovarian development is rare. Chromosomal abnormalities such as Turner’s syndrome may occur (see Ch. 5).

Pituitary disorders

Disorders of the pituitary gland may result in the secretion of abnormal levels of hormones which affect the sensitive feedback mechanism ultimately affecting hormones of the menstrual cycle (see Ch. 5).

Dysmenorrhoea

For some women, the first hours or the first day are the most painful. Dragging sensations from the umbilical area down to the groins and thighs may be experienced, or the pain may be severe, colicky or spasmodic in nature across the abdomen and back. The pain may be so distracting as to interfere with the woman’s usual daily activities: 45–95% of menstruating women can be affected (Proctor & Farquhar 2006). Absenteeism from work and school is common due to symptoms of dysmenorrhea.

Two types of dysmenorrhoea are described:

Primary dysmenorrhoea

Pathophysiology

Misunderstandings about the physical changes of menstruation and the nature of dysmenorrhoea may underlie ineffective management. Education about the nature of dysmenorrhoea and its effective management should therefore be addressed with young girls and their parents as appropriate (Box 7.1).

Medical management

Treatment

Treatment for dysmenorrhoea aims to relieve pain or symptoms either by affecting the physiological mechanisms behind menstrual pain (such as prostaglandin production) or by relieving symptoms. Treatments using simple analgesics such as paracetamol, aspirin, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting prostaglandin production. An oral contraceptive may be indicated as these inhibit ovulation. A levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system may also be of use. Slow release of levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity prevents thickening of the endometrium. Women may experience amenorrhoea with resultant reduction in dysmenorrhoea. The levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system has also been shown to be effective in reducing dysmenorrhoea in women with endometriosis after one year (Vercellini et al 2003).

Nursing management and health promotion: primary dysmenorrhoea

Planning care

Evaluating care

A pain verbal rating scale could be used by the patient (see Ch. 19). If optimal pain relief is not achieved it may be necessary to amend analgesic regimens. Relaxation exercises should be used while the effects of analgesics are awaited. The achievement of the patient’s goals will be her first step in a change of lifestyle. Further support and encouragement may be given by her mother, friend, partner, a school or practice nurse or the GP.

Secondary dysmenorrhoea

Pathophysiology

Medical management

Treatment

Investigations may involve hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. A laparoscopy may be performed if endometriosis is suspected. The presence of fibroids or polyps will be treated appropriately (see pp. 208–210). Pelvic inflammation can be treated by antibiotics. An analgesic drug can be prescribed that is suitable for inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, e.g. mefenamic acid.

Nursing management and health promotion: secondary dysmenorrhoea

Pre- and postoperative care planning will be needed if surgical procedures are planned (see Ch. 26). At the time of discharge the patient’s future prospects for an improved pattern of menstrual cycles should be better.

Abnormal uterine bleeding

Abnormal uterine bleeding is described according to the rhythm or pattern of blood loss:

Menorrhagia

Menorrhagia may be ovarian or uterine in origin.

Pathophysiology

Ovarian

Ovarian lesions are of two types:

Uterine

Medical management

Treatment

Endometrial ablation is another treatment option for menorrhagia and is one of several minimally invasive procedures developed over recent years. It is undertaken as a day case procedure and is increasingly done as an outpatient procedure (Clark & Gupta 2005). This involves destroying the endometrium, preventing its cyclical regeneration. For many women the associated physical, social and psychological implications make it preferable to more extensive surgery such as hysterectomy. Different techniques have developed but they are based on the same principle which involves the introduction of instruments to destroy the endometrium using heat via a hysteroscope. These include:

Metrorrhagia

Pathophysiology

Medical management

Investigations

Liquid-based cytology smear tests have replaced Papanicolaou (Pap) smears as the routine investigation to evaluate changes in cells obtained from the cervix (see p. 212). A high vaginal swab (HVS) will allow the identification of infection (bacterial or fungal) or parasitic infestations. Where endometrial bleeding is suspected it is important to perform a hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy to rule out cancer.

Premenstrual syndrome

Most women will experience some symptoms during their reproductive life but 40% of women are thought to suffer from true PMS, with about 5–10% experiencing symptoms that are severe enough to disrupt their lives (Andrews 2005).

Signs and symptoms are varied but include:

Pathophysiology

Numerous theories have been suggested to explain PMS, but the precise cause remains unknown.

Fluid retention or redistribution

Redistribution of body fluids in intracellular and extracellular compartments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree