CHAPTER 2 Nursing patients with cardiovascular disorders

Introduction

The cardiovascular system consists of the heart and blood vessels. It is a closed circuit and is responsible for ensuring that blood flows throughout the body. Heart and circulatory disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), includes all the diseases of the heart and blood vessels. The two main diseases in this category are coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, but CVD also includes congenital heart disease and a range of other diseases of the heart and blood vessels. CVD is the greatest cause of death in the UK, accounting for 34% of the deaths in 2007, a total of over 193 000 people (British Heart Foundation [BHF] 2008). It is the main cause of disability in the UK and as such is likely to be encountered by all nurses, whether hospital- or community-based. CVD also has an immense impact on society in human terms. Bereavement, disability, changing roles within the family and society, and fear are some examples of its consequences. CVD is costly in financial terms, imposing a significant annual burden on the UK economy. CVD cost the health care system in the UK around £3.2 million in 2006 – a cost per capita of just over £50. However, the majority of the costs of CVD fall outside the health care system and are due to illness and death in those of working age and the economic effects on their families and friends who care for them. The overall cost of CVD to the UK economy is estimated to be £30.7 billion per annum (BHF 2008).

Many cardiovascular diseases take the form of progressive debilitating illness, often becoming chronic with intermittent acute episodes. In contrast, a heart attack (myocardial infarction, MI) is often sudden and unexpected, arousing acute distress in the individual and family as they confront a life-threatening crisis. Cardiovascular nursing is evolving as nurses move on from practising the skills of advanced life support, cannulation and phlebotomy, to taking greater responsibility for decisions that influence patient care management. Nursing care has historically ranged from acute care management to long-term support (Ashworth 1992) and includes:

Government frameworks and standards of care, such as the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease (Department of Health [DH] 2000), have resulted in opportunities for nurses to lead and develop CVD services in and between primary, secondary and tertiary care environments. Over the past decade, experienced nurses have increasingly become part of the multidisciplinary team, admitting and discharging patients from specialist units via triage and fast-tracking, prescribing and titrating drug therapies, coordinating specialised clinics and leading rehabilitation and health promotion programmes (Quinn & Morse 2003). For an example of a critical pathway, see website Figure 2.1.

Anatomy and physiology of the heart

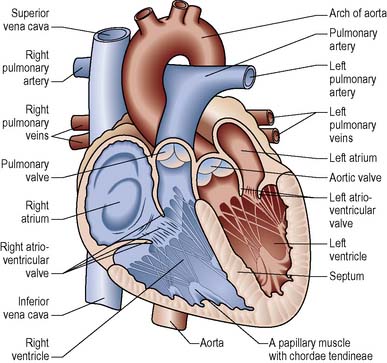

The heart is a hollow, four-chambered muscular organ that generates pressure changes resulting in the propulsion of blood around the vascular system. The right side of the heart pumps blood around the pulmonary system where gaseous exchange takes place and then on to the left side of the heart. The left side of the heart operates under much greater pressure to enable it to pump blood around the systemic circulation. The various chambers of the heart are illustrated in Figure 2.1.

The heart is composed of different types of tissue:

Coronary blood supply

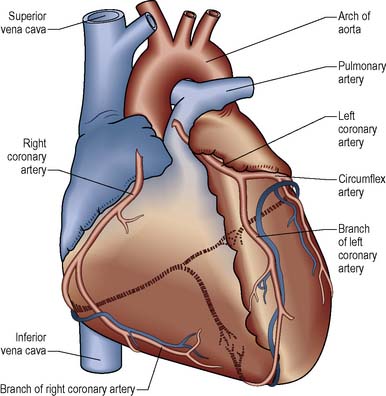

Like all major organs, the heart requires blood flow to maintain cellular activity. It receives its blood supply from the right and left coronary arteries which arise from the aorta just beyond the aortic valve and run over the outer surface of the heart (Figure 2.2).

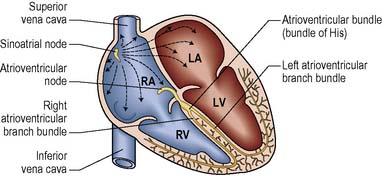

The left coronary artery runs towards the left side of the heart and divides into two major branches: the left anterior interventricular branch or left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the circumflex artery (CX). The LAD follows the anterior ventricular sulcus and supplies blood to the interventricular septum and the anterior walls of both ventricles. The CX follows the coronary sulcus and supplies blood to the lateral and posterior regions of the left atrium and left ventricle. The right coronary artery (RCA) runs to the right side of the heart and divides into two branches: the posterior interventricular artery and the marginal artery. The posterior interventricular artery supplies blood to the posterior ventricular walls and the marginal artery supplies the right ventricle. The RCA supplies the sinoatrial (SA) and atrioventricular (AV) nodes in about 60% of cases (Figure 2.3).

The conducting system of the heart

The main ions (electrically charged particles) involved in the electrical activation of cardiac muscle are sodium (Na+), potassium (K+) and calcium (Ca2+). Electrical activity occurs due to the movement of these and other ions in and out of the cells thereby altering the electrical charge of the cell. Cells at rest (known as polarised) are negatively charged on the inside whilst cells that are electrically activated (known as depolarised) are positively charged on the inside. The electrical charge on the surface of an automatic cell leaks away until a certain threshold is reached and spontaneous action potential is generated over the whole cell surface. The automatic cells are found in the cardiac conducting system (see Figure 2.3), which consists of:

Electrocardiography

The sequence of electrical events produced at each heartbeat has arbitrarily been labelled P, Q, R, S and T (Figure 2.4).

The T wave

represents the electrical recovery or repolarisation of the ventricular muscle. Occasionally, a U wave can be observed following the T wave. The origin of this wave is not well understood, but it is considered significant in a state of hypokalaemia. For more details on the ECG see Riley (2007a) in Further reading.

Cardiac cycle

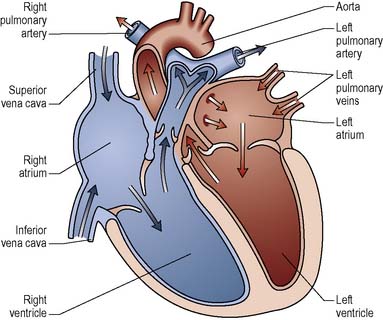

During diastole, which normally lasts about 0.4 s, blood enters the relaxed atria and flows passively into the ventricles. The atria contract fractionally before the ventricles and complete ventricular filling. As the ventricles begin to contract, ventricular pressure increases and for a short time (isometric phase) all four valves are closed and the volume of blood in the ventricles remains constant. Increasing pressure eventually forces the pulmonary and aortic valves to open and blood is ejected into the pulmonary artery and aorta. When the ventricles stop contracting, the pressure within them falls below that in the major blood vessels, the aortic and pulmonary valves close and the cycle begins again with diastole (Figure 2.5).

The primary factors that determine cardiac output are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree