CHAPTER 11 Nursing patients with blood disorders

Introduction

Disorders of the blood are diverse and the nursing care of a patient with a blood disorder will depend on the type and nature of the condition. They can be acute or chronic and can affect all age groups. Some blood disorders, such as haemophilia, are sex-linked. Others, such as the hereditary haemoglobinopathies sickle cell disease and thalassaemia, are more prevalent among certain groups whereas others, such as iron-deficiency anaemia, occur generally. Some blood disorders, such as acute leukaemia, are life-threatening and require urgent treatment. Nursing patients with a blood disorder is challenging and requires expert knowledge and skills in order to ensure individualised, holistic care. This chapter provides a brief overview of the anatomy and physiology of blood and haematopoiesis (blood cell production) (see Further reading, e.g. Tortora & Derrickson 2009).

Anatomy and physiology

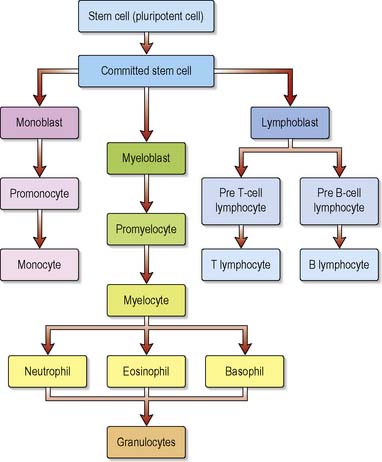

All blood cells originate from pluripotent haematopoietic stem cells. Stem cells are capable of self-renewal, proliferation and differentiation into separate cell lineages, which give rise to distinct blood cell populations. This multistep process, known as haematopoiesis, is stimulated and regulated by a range of cytokines, hormones and growth factors including erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) and interleukins (Hoffbrand et al 2006).

Blood cells have a limited lifespan and an estimated 100 billion new blood cells are required daily in order to maintain a healthy, steady state (Huether & McCance 2008). Consequently, haematopoiesis is a continual process which takes place in different anatomical sites throughout the lifespan. These include the embryonic yolk sac, the fetal liver and spleen, and in all bone marrow during infancy. From childhood onwards, red bone marrow is progressively replaced with fat. In adults haematopoiesis occurs primarily in the medullary cavity of flat bones. Sites include the:

Cellular components of blood

The three main cellular components of blood are:

Erythrocytes (red blood cells)

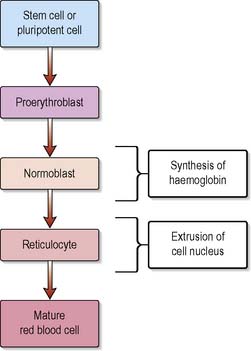

The total number of circulating erythrocytes remains fairly stable at 3.8–6.5 × 1012 cells/L, with women having less than men. Erythropoietin has a vital role in the regulation of red cell production (erythropoiesis) and is produced mainly by the kidneys in response to tissue hypoxia. During maturation, the erythrocyte synthesises haemoglobin and extrudes its nucleus, thereby rendering the mature cell incapable of reproduction, repair, growth or haemoglobin production (Figure 11.1). The average lifespan of a red blood cell (RBC) is 120 days, after which it is sequestered in the spleen where it is destroyed by the phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system (also known as mononuclear–phagocytic system).

Leucocytes (white blood cells)

Leucocytes or white blood cells (WBCs), of which there are several distinct types, make up approximately 1% of blood volume and are instrumental in defending the body against infection. The total number of WBCs is between 4.0 and 11.0 × 109 cells/L. Leucocyte maturation is regulated by specific haematopoietic growth factors such as granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and their lifespan will vary according to type (Figure 11.2). For example, neutrophils circulate for about 7–8 hours in the blood before migrating into the tissues, where they die after a few days. Lymphocytes may live from 100 days to several years, whereas macrophages can survive for many years.

Eosinophils

circulate in the peripheral blood for approximately 5 hours. Phagocytic eosinophils exit to the tissues where they are responsible for defence against infestation by parasites. Eosinophils also have a role in allergic responses (see Ch. 6).

Basophils

comprise the smallest number of WBCs. Basophils and mast cells contain heparin and histamine and are involved in anaphylactic, hypersensitivity and inflammatory responses (see Ch. 6).

Monocytes

The largest of the WBCs, monocytes start as immature macrophages which are present in the blood for 20–40 hours before travelling to tissue sites where they mature into powerful phagocytes. Tissue macrophages also process and present antigens to lymphoid cells and play a role in the production of cytokines and growth factors important for haematopoiesis, inflammation and cellular responses (Mehta & Hoffbrand 2009).

Lymphocytes

are the chief cells of the immune response and make up approximately 36% of total leucocyte count. Lymphocytes mature in either bone marrow (B lymphocytes or B cells) or the thymus gland (T lymphocytes or T cells). B lymphocytes are responsible for antibody-mediated (humoral) immunity while T lymphocytes play an integral role in specific cell-mediated (cellular) immunity (see Ch. 6). Natural killer (NK) cells are a subset of lymphocytes which share many features of cytotoxic T cells, a type of T lymphocytes.

Blood groups

ABO blood groups

A person with the antigen A (blood group A) has anti-B antibodies (also called agglutinins) in the plasma whereas a person with antigen B (blood group B) has the anti-A antibodies. A person with both antigens A and B (blood group AB) has no antibodies in the plasma, whilst a person with neither A nor B antigens (blood group O) has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies in the plasma (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 Antigens and antibodies present in ABO blood groups

| ABO Blood Group | Antigen on Red Blood Cell Membrane | Antibodies Present in the Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| A | A | Anti-B |

| B | B | Anti-A |

| AB | A and B | None |

| O | None | Anti-A and anti-B |

Blood transfusion

Blood transfusion, the administration of whole blood or blood products donated by one person to another, makes it possible to save lives. Transfusion does, however, expose patients to the risk of potentially fatal complications, e.g. infection, haemolytic reactions or receiving an incompatible unit of blood (Box 11.1). Box 11.2 provides an opportunity for you to consider how nurses can improve safety during transfusion.

Box 11.1 Reflection

Serious hazards of transfusion of blood and blood products

The SHOT (Serious Hazards of Transfusion) Annual Report 2007 analysed 332 adverse events. These included 46 ‘wrong blood’ events where a patient received a blood component intended for a different patient or of an incorrect group (SHOT 2007).

Activities

Box 11.2 Evidence-based practice

Promoting safer blood transfusion

Results from a national audit of bedside transfusion practice revealed that patients in the UK are at risk of misidentification and poor monitoring when undergoing a blood transfusion. Parris & Grant-Casey (2007) identify the implications of the audit findings and explore initiatives to improve blood transfusion safety.

![]() See website Critical thinking question 11.1

See website Critical thinking question 11.1

Many people who require blood transfusions fear being infected with a transmittable disease, such as HIV, hepatitis or variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD). It is therefore necessary that the screening procedures undertaken on all blood donors and the testing and processing of donated blood are explained. For instance, in the UK, white cells are routinely removed from donated blood to minimise the risk of transmitting vCJD. Some religious groups such as Jehovah’s Witnesses may refuse blood transfusions while some others may wish to consult family and religious leaders before giving consent. The blood transfusion products readily available are listed in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2 Blood transfusion products available

| Product | Indications for Use | Special Points |

|---|---|---|

| Whole blood (infrequently given) | Acute, severe bleeding requiring replacement of red blood cells and plasma and coagulation factors | Stored at 4°C for up to 35 days Platelets and coagulation factors have much reduced viability |

| Fresh whole blood (infrequently given) | As above | Blood <24 h old, therefore more likely to contain viable coagulation factors |

| Red cell concentrate | Replacement of red blood cells only. Therefore used when haemoglobin level is low | Up to 200 mL plasma removed per 500 mL blood |

| Washed red cells | As for red cell concentrate Specially prepared to remove antigens | Prevents anaphylactic transfusion reactions |

| Frozen red cells | As for red cell concentrate | Storage lifespan lengthened, therefore useful for rare blood groups |

| Platelet concentrate | Patients with platelet count <20 × 109cells/L but not actively bleeding | Platelet units from blood banks contain platelets from many units of blood, therefore there are frequent reactions. Patient may require i.v. hydrocortisone plus i.v. chlorphenamine prior to transfusion. Stored at 20°C. Viability of platelet concentrate only 24 h. Never place in fridge |

| Other blood components | ||

| Fresh frozen plasma | Hereditary or acquired bleeding disorder Volume replacement Liver disease Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) | Frozen within 6 h of cell separation and viable for 1 year. Once thawed, use within 30 min |

| Cryoprecipitate (factor VIII, fibrinogen) | Haemophilia | From fresh frozen plasma Last part to thaw is cryoprecipitate |

| Factor VIII | Haemophilia A | From fresh frozen powder (half-life 12 h) |

| Factor IX | Haemophilia B (Christmas disease) | |

| Human immunoglobulin | Passive immunity, especially immunosuppressed patients | |

| Albumin solution | Hypoproteinaemic oedema, ascites, acute volume replacement | |

Disorders of the blood

Investigations used in the diagnosis of blood disorders

Blood tests

Bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy

This involves the removal of a small amount of bone marrow from the posterior iliac crest or sternum. This is mounted on slides and stained for microscopic examination. This test is not done routinely but is indicated if there is evidence of severe anaemia or of another blood disorder such as aplastic anaemia or leukaemia (Box 11.3).

Disorders of red blood cells – anaemias (general aspects)

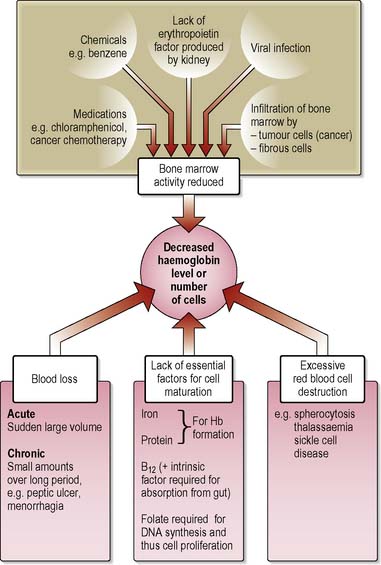

Anaemias are a complex group of blood disorders found in all age groups resulting from a reduction in the number of RBCs and/or haemoglobin concentration in the blood (Figure 11.3). Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO et al 2001) as haemoglobin level less than 13.0 g/dL in males over 15 years of age, less than 12 g/dL in non-pregnant females over 15 years and children aged 12–14 years, and less than 11 g/dL in pregnancy, anaemia may be caused by:

Clinical presentation

General problems associated with anaemia

Nutrition

The anaemic patient will require a high-protein diet which includes all the nutrients necessary for red cell production (p. 368). Breathlessness, a lack of energy to shop and prepare food, a sore mouth and dysphagia may all contribute to anorexia. A sore mouth can be especially distressing and the nurse will need to carry out an oral assessment using an appropriate assessment tool. Care should include not only that which will improve and heal the mouth but also relevant health education about oral hygiene including teeth cleaning and/or care of dentures, mouth washes and lip care.

Safety

Faintness, light-headedness and sensitivity to cold make the anaemic patient prone to injury. As the body responds to poor oxygenation by preserving the blood supply to the essential organs, anaemic patients will have poor peripheral circulation and, consequently, fragile skin. The reduced attention span typical of anaemic patients will also make them vulnerable to falls, minor injuries and hypothermia. Anaemic patients should be warned against changing position suddenly, especially from lying to standing, and should be given instruction on first aid for minor injuries and on the prevention of hypothermia (see Ch. 22).

Skin integrity

The anaemic patient’s reduced oxygen and nutrient supply to the skin increases the risk of pressure ulcers. Hypoxic skin will not necessarily break down quickly, but if damaged it will take longer than usual to heal. An initial and continuing assessment of all pressure areas should be made using appropriate risk assessment tools (see Ch. 23).

Once the patient’s level of risk of developing pressure ulcers has been determined, appropriate interventions should be instigated. These will include ensuring that the patient’s position is changed 2 hourly, the use of appropriate pressure-relieving devices and instructing the patient about the importance of regular re-positioning (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [EPUAP] 2008).

Specific anaemias

Iron deficiency anaemia

Iron deficiency anaemia affects an estimated 600 million people (Craig et al 2006) and is recognised as one of the most common types of anaemia worldwide.

Pathophysiology

Iron is a constituent of haemoglobin and is essential for cellular function and erythropoiesis. Iron deficiency anaemia arises when absorption of iron from food does not meet the daily requirements. This may be due to chronic blood loss (discussed more fully on pp. 375–376) or malabsorption, although the most common cause is inadequate dietary intake (Mehta & Hoffbrand 2009).

Clinical presentation

As the onset of iron deficiency anaemia is usually very gradual, the patient may not seek medical attention until some time after symptoms appear. The most common presenting features are tiredness and pallor, although any of the other general symptoms of anaemia (see p. 373) may be apparent. Signs and symptoms specific to iron deficiency anaemia include:

Investigations

Blood samples will be taken for tests, such as FBC, haemoglobin level, MCV, MCH, ESR, blood film, serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC). Estimates of ferritin (an iron storage protein) measure iron stores and a subnormal level is caused by iron deficiency (Craig et al 2006). Other investigations such as faecal occult blood testing (FOB), endoscopy or barium studies may be undertaken to establish the cause of the deficiency.

Treatment

Nursing management and health promotion: iron deficiency anaemia

Many of the nursing considerations for the general care of anaemic patients (see pp. 373–374) are relevant for iron deficiency anaemia. Other nursing management strategies will focus on patient education and discharge planning with an emphasis on health promotion.

Patient education and health promotion

Helping the patient to understand the disorder will assist in promoting compliance with treatment. Information about foods that are rich in available iron should be given and advice on selecting and budgeting for a well-balanced diet may also be needed (Box 11.4). Assessing the patient’s perception of the problem, level of knowledge and sociocultural background can help to ensure that the advice offered is relevant and comprehensible. Referral to a social worker may also be appropriate.

Box 11.4 Reflection

Anaemia resulting from chronic blood loss

Iron deficiency anaemia may result from blood loss. This may either be:

Chronic blood loss, which will be addressed in this section, is not uncommon and may present secondary to a number of other disorders. Frequently, it is only when a diagnosis of iron deficiency anaemia has been established that the underlying cause is suspected. The most common causes of chronic blood loss are listed in Box 11.5.

Box 11.5 Information

Clinical presentation

Treatment

Nursing management and health promotion: anaemia due to chronic blood loss

The patient may be feeling apprehensive and frightened, and providing clear information about investigations, especially invasive procedures such as endoscopy (see Ch. 4), may help to alleviate anxiety. Information should address any pre-investigative preparation such as fasting, approximate durations of tests and what they will involve. It is also important to discuss whether the patient will be fit to return home unaccompanied after investigative procedures and when the results can be expected.

Megaloblastic anaemias

Vitamin B12 deficiency

As vitamin B12 is found predominantly in meat, eggs and dairy products, vegans are at particular risk; however, the most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency is malabsorption due to pernicious anaemia. This condition, caused by autoimmune gastritis, affects 1 in 100 people of all races over the age of 60 (Hoffbrand & Provan 2007). It occurs when the gastric mucosa atrophies, resulting in a failure to produce intrinsic factor required for vitamin B12 absorption. Table 11.3 outlines other causes.

Table 11.3 Causes of the megaloblastic anaemias

| Type | Causes |

|---|---|

| Folate deficiency | Inadequate dietary intake |

| Malabsorption: | |

| Increased demands: | |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | Inadequate vitamin B12 in diet (especially vegans) Malabsorption: • pernicious anaemia caused by autoimmune gastritis that leads to gastric atrophy and intrinsic factor deficiency |

Folate deficiency

Folates are found in green leafy vegetables, potatoes, fruits, fortified breakfast cereals and bread, liver, milk and dairy products, and yeast extract. Deficiency is commonly due to an inadequate dietary intake of folic acid. (See Table 11.3 for other causes.) This may occur either alone or in conjunction with a condition such as pregnancy, in which folate utilisation is increased. Fetal abnormalities, e.g. neural tube defects (NTDs), are associated with inadequate folate intake around the time of conception and during the first few weeks of pregnancy.

Clinical presentation

Investigations

Blood tests will be similar to those for the diagnosis of iron deficiency anaemia (see p. 374) Additional specific diagnostic blood tests for megaloblastic anaemia include serum B12 levels and folate assays. Other investigations may include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree