CHAPTER 33 Nursing patients who need palliative care

What is palliative care?

The most widely accepted definition of palliative care was first provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1990). The most recent version states:

This clearly portrays palliative care as an active approach to assessing and managing care needs, far from the perspective that ‘nothing more can be done’ for the patient when their illness cannot be cured. The aim is to support the patient in living as comfortable and fulfilling a life as possible as their illness progresses towards death. It is important for health care professionals to recognise that dying is more than a physical experience and that suffering has psychological, social and spiritual dimensions which can also envelop those closest to the patient. This requires consideration not just of the physical disease process, but also the effects on the patient as an individual and their family when planning and delivering care. The palliative care approach is therefore person-centred, holistic and multidimensional (Box 33.1).

Box 33.1 Reflection

Principles of palliative care

The World Health Organization sets out what palliative care involves, for example relieving pain and other distressing symptoms, and a holistic approach through the integration of the physical, psychological and spiritual aspects of care (WHO 2009).

Effective palliative care is essential, especially so when you consider that in most countries the majority of people will first access medical services when their illness is already advanced (WHO 2009).

Activities

Historically, a number of terms have been associated with palliative care. These include ‘care of the dying’, ‘hospice care’, ‘supportive care’, ‘terminal care’ and ‘end-of-life care’. Birley & Morgan (2005) highlight that these terms are often used interchangeably and thus are open to misinterpretation.

A number of factors may have contributed to the varied terminology used to describe palliative care. Improved health and social care alongside advances in medical technologies have caused an epidemiological shift in the main causes of death within the developed world. From the late nineteenth century onwards, mortality rates from infectious diseases, childhood illnesses and maternal deaths have gradually declined. As a result, the average life expectancy has significantly increased and has now reached the highest level on record for both men and women (Office for National Statistics 2008). This has led to a steady rise in the incidence of life-limiting illnesses with more prolonged disease trajectories such as cancer, chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease, for which more sophisticated diagnostic and treatment options have improved prognosis and length of survival. This means that an increasing number of people are living longer with progressive and ultimately fatal conditions. Kellehear (2007) provides a comprehensive and thought-provoking account of how in modern society the predominant conception of dying has shifted from an event characterised by a rapidly fatal or sudden demise, to that of a process of transition. This is now commonly referred to as ‘living whilst dying’ and ‘the dying process’, which can extend over weeks, months, even years.

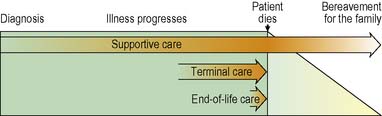

Following the World Health Organization definition, the palliative approach is applicable from the time a life-limiting illness is diagnosed, throughout the patient’s illness and into bereavement support for the family (Figure 33.1). This includes all stages of the disease trajectory including whilst the patient is receiving treatments which, although cure is not possible, may prolong their life or help control symptoms. Supportive care is integral to the palliative approach in helping the patient and family cope with the impact of the disease and the uncertainties and losses of the dying process. Terminal care refers to the last stage of the patient’s illness, where there is increasing disability and dependence and death is anticipated in the near future. End-of-life care is delivered in the last days of the patient’s life and will be considered in more depth later in this chapter.

The development of palliative care

The need to apply the principles of the palliative care approach developed within hospices to the care of patients dying in their own home, hospitals and nursing homes has received increasing attention. From reviewing place of death within England and Wales over the past 30 years, Gomes & Higginson (2008) highlight that most people with a life-limiting illness are cared for and die in these settings. The full breakdown of place of death is approximately:

Furthermore, Gomes & Higginson (2008) project that, in line with an aging population, the demand for palliative care in general hospitals and the community setting will rise significantly by 2030.

As the majority of care for the dying is delivered within hospitals, the community and nursing homes, palliative care is a core responsibility of all health and social care professionals in these settings. Yet, increasing societal awareness and expectations of palliative care contrast sharply with reports of variation and deficiencies in care provision and the unmet needs of dying patients (Costello 2004, National Audit Office 2008). This has prompted development in two main areas:

The expansion of hospices and specialist palliative care services

Hospices were the first specialist palliative care services and there are currently over 200 inpatient units in the UK (Audit Scotland 2008, National Council for Palliative Care 2007). Patients may be admitted for a variety of reasons including assessment, rehabilitation and symptom management, respite stays to give families and carers a short break, and terminal care.

The core dimensions of specialist palliative care services are:

Specialist palliative care services are not involved in the care of all patients with a life-limiting illness but operate on an advisory and referral basis. Other health and social care professionals, such as GPs and district nurses in the community and ward teams in hospitals, can request advice regarding how to address the needs of patients and families under their care. They can also refer patients and families with more complex needs for specialist assessment and direct intervention, for example in managing difficult pain and other symptoms, and psychological and spiritual distress. In this way, the expertise of the specialist team is shared through joint-working to address palliative care needs, although the referring team retains overall clinical control and responsibility for the patient (Box 33.2).

Supporting general palliative care within community and hospital settings

Current health care strategy emphasises the need to ensure access to a high standard of palliative care for all patients with a life-limiting illness within all care settings (Department of Health [DH] 2008a, Scottish Government 2008). Traditionally, hospices have provided care predominantly for people with cancer. It would appear that this is generally still the case from reports that during 2006–2007, 93% of those referred to specialist palliative care services across the UK had a diagnosis of malignancy (National Council for Palliative Care 2007). Cancer remains a leading cause of death in the developed world (see Ch. 31). Studies have identified, however, that people dying from non-malignant life-limiting illnesses such as advanced cardiac and respiratory diseases, dementia and stroke have just as great a need for palliative care as those with cancer (Solano et al 2006).

It has already been highlighted that the incidence of both malignant and non-malignant life-limiting illnesses is rising, with a corresponding increase in demand for palliative care. In addition, greater awareness of inequity of access to effective care across settings and for some patient groups has made strengthening the delivery of palliative care within mainstream hospital and community services a priority. Developments towards this include the introduction of The Gold Standards Framework (Thomas 2003) and the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying (Ellershaw & Wilkinson 2003) to support the delivery of a high standard of palliative care in all settings.

The palliative care approach in practice

The palliative care approach – a model for practice

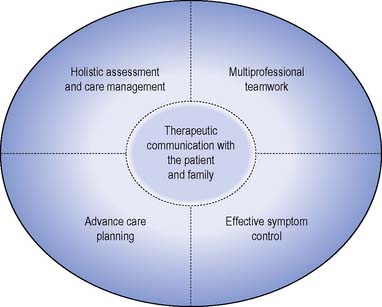

The model for practice is presented as a guide for the clinical nurse in the twenty first century (Figure 33.2). In accordance with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (2008) The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Professional Practice, this nurse is a critical thinker. This means challenging assumptions and looking for creative and workable solutions to problems, critically reading literature and appraising research and, in partnership with the multiprofessional team, implementing reflective, evidence-based practice.

Therapeutic communication

The purpose of therapeutic communication is primarily supportive to the patient and family in the context of care provision and provides the medium by which professionals can gain an accurate understanding of care needs. Therapeutic communication also allows information needs to be identified and addressed, at a level appropriate to the individual patient and family to ensure their understanding. From summarising research in this area, Duke & Bailey (2008) report that the effective provision of information has been shown to reduce distress and enhance compliance with treatment and the ability to cope with the practicalities of living with and dying from a life-limiting illness. Professionals have a responsibility to be aware of how well they communicate with patients and families, and this can be supported by critical reflection on practice. This responsibility extends to then developing the necessary knowledge, skills and confidence in the use of strategies which support effective interaction with the patients and families under their care.

The ideal situation for therapeutic communication is one in which privacy is provided without interruption. The patient’s physical comfort should be attended to. The purpose should be made explicit and the patient’s consent obtained to proceed. Patients and families need to feel secure that confidentiality will be maintained. It is often believed that patients realise that they are being cared for by a multiprofessional team and that they therefore implicitly agree that information given to one professional may be openly shared with others. This should not be assumed. It is useful to remind patients and families that information which is relevant to their care is shared within the multiprofessional team and to emphasise that they do not have to talk about areas they prefer to keep private. The ethics of confidentiality are beyond the scope of this chapter (see Nursing and Midwifery Council 2008 and Further reading, e.g. Dimond 2008, Griffith & Tengah 2008).

There may be occasions where the nurse does not have the information required to answer a question or address a concern. Honesty is the best policy, alongside acknowledgement that the question or concern is important to the person. Reassurance can be given that the nurse will direct their question or concern to an appropriate member of the multiprofessional team. Dying patients and their families do not expect every professional to have all the answers; however, dishonesty or failing to acknowledge their concerns can undermine their trust, confidence in and openness with the multiprofessional team (Costello 2004).

When speaking to families it is important to note that where the patient has capacity their permission and wishes should be ascertained regarding disclosure of information. Family members can offer useful information regarding care needs and may be the greatest source of support for the patient, including supporting their wish to be cared for at home. Family dynamics do vary, however, and therefore an understanding of roles and relationships ensures that the patient’s wishes can be respected whilst addressing the concerns of the family, reinforcing the principle that family support is an integral part of palliative care (Payne 2007).

Holistic assessment and care management

Holistic assessment is a key activity in palliative care and directs the use of appropriate strategies for care needs associated with the physical, psychological, spiritual and social impact of the illness on the patient and family. A number of approaches may be used. These include quantitative measures such as rating scales to measure the severity of a symptom, for example pain assessment tools (see Ch. 19), and more qualitative approaches such as history taking. Whatever approach is used it is imperative that it is multidimensional so that the assessment captures a full and comprehensive picture of the palliative care needs of the patient and family. Some key assessment questions which can be adapted for a holistic assessment include:

Multiprofessional teamwork

Effective multiprofessional teamwork is, however, more than just a group of professionals involved in the care of the same patient and family. Speck (2006) outlines a number of challenges for the multiprofessional team in palliative care. These include ensuring a shared understanding of goals and objectives and that a blurring of traditional role boundaries can occur when all professionals share a holistic perspective. Effective communication and coordination of activity across a wide team is essential to avoid the risk of fragmented care and key needs not being identified and properly addressed.

Advance care planning

Ascertaining the wishes of the patient regarding future care and treatment is an important part of care planning and nurses play a key role in acting as the patient’s advocate and supporting an informed choice. This may include decisions concerning resuscitation which can present a number of ethical and practice issues for nurses. The General Medical Council GMC (2010) and the Scottish Government (2008) have produced guidance regarding this sensitive area of care.

The patient’s preferences regarding place of care during their illness and at the end of life should also be explored using therapeutic communication. Patient’s wishes may change over time and therefore decisions should be sensitively revisited as appropriate when circumstances change. Recently, the use of the Preferred Place of Care document to communicate and support patient choice across care settings has been advocated in England and Wales (Department of Health 2008b).

Effective symptom control

The key components of symptom control in palliative care are well described (see Further reading, e.g. Hanks et al 2009). In summary, the multiprofessional team must work with the patient to:

The effective control of some common distressing symptoms is discussed below.

Nursing management and health promotion: common distressing symptoms

This part of the chapter focuses on the management of four common distressing symptoms: pain, nausea and vomiting, constipation and breathlessness. See Further reading (e.g. NHS Lothian 2008, Fallon & Hanks 2007) for information about other symptoms, such as cough, hiccup, delirium, etc.

Pain

Pain is one of the most feared symptoms of a terminal illness and is estimated to occur in up to 70% of patients with cancer and 65% of patients dying from non-malignant diseases (Fallon & McConnell 2006). Despite the complexity of this symptom, a vast amount of knowledge is available regarding strategies for effective management. However, pain that is not identified will not be treated, and pain will not be treated vigorously enough if its severity is underestimated.

It has now been accepted that the patient’s self-report is the most reliable indicator of pain. However there are challenges to this in practice. Self-report of pain may not be an option in the confused or non-verbal patient. Observation of behaviour and proxy reporting from carers then becomes the main method of assessing the pain of these individuals (Royal College of Physicians, British Pain Society and British Geriatrics Society 2007).

The severity of pain can be assessed using visual or numerical analogue scales, for example by asking the patient to score their pain on a scale of 1–10 where 0 equals no pain and 10 equals the most severe pain possible (see Ch. 19). Some patients may prefer rating their pain as none/mild/moderate/severe or simply using their own terms. It is important to find a way of rating pain severity that is clearly understood by both the patient and the multiprofessional team. From this shared understanding of how bad the pain feels, management strategies can be targeted most effectively and patient distress minimised. Professionals must remember that in a palliative context, the patient may have been experiencing pain for some time. The physiological indicators common to those with acute pain, e.g. tachycardia and raised blood pressure, may therefore be absent.

Principles have been established by the WHO (1986, 1996) to guide health care professionals in the effective management of pain. In addition, guidelines such as the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2008) publication Control of Pain in Adults with Cancer are readily available online. Registered nurses must have a working knowledge of these principles and guidelines to promote good multiprofessional understanding and patient confidence.