Nursing Models

Normal Science for Nursing Practice

Angela F. Wood∗

In the sciences, the formation of specialized journals, the foundation of specialist societies and claim for a special place in the curriculum have usually been associated with a group’s first reception of a single paradigm.

Nursing Models and Their Theories in Nursing Practice

The use of nursing models and their theories in nursing practice is presented in this chapter, documenting various areas of application and utilization of the models as reported in the nursing literature. As the premise in the third edition (2006) set forth, the shift from theory development to theory utilization restores a proper relationship between theory and practice for a professional discipline such as nursing. The importance of this shift was supported by Levine’s (1995) comment, when she stated in regard to Fawcett’s clarification of models from theories, “It may be that the first prerequisite for effective use of theory in practice… rest[s] on just such a clarification” (p. 12). The literature continues to verify that nursing models and their theories have practical utility for nursing with specific details in areas of practice (Bond, Eshah, Bani-Khaled, et al., 2011; Donohue-Porter, Forbes, & White, 2011; Im & Chang, 2012; McCrae, 2011).

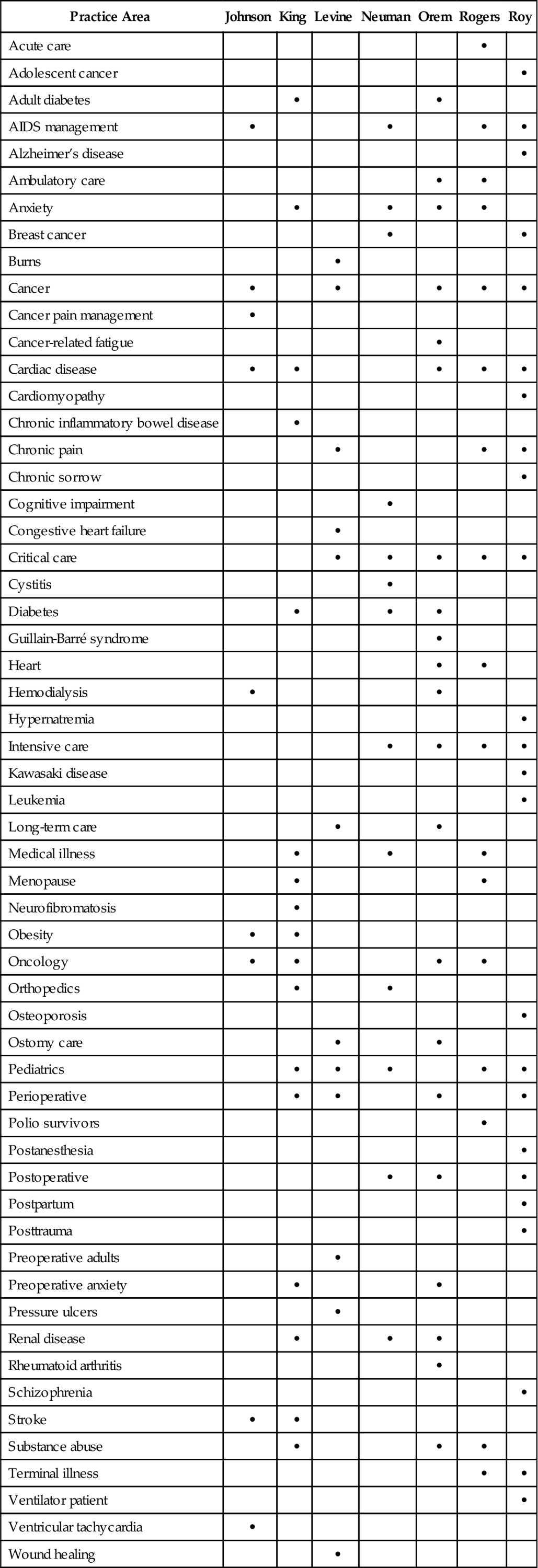

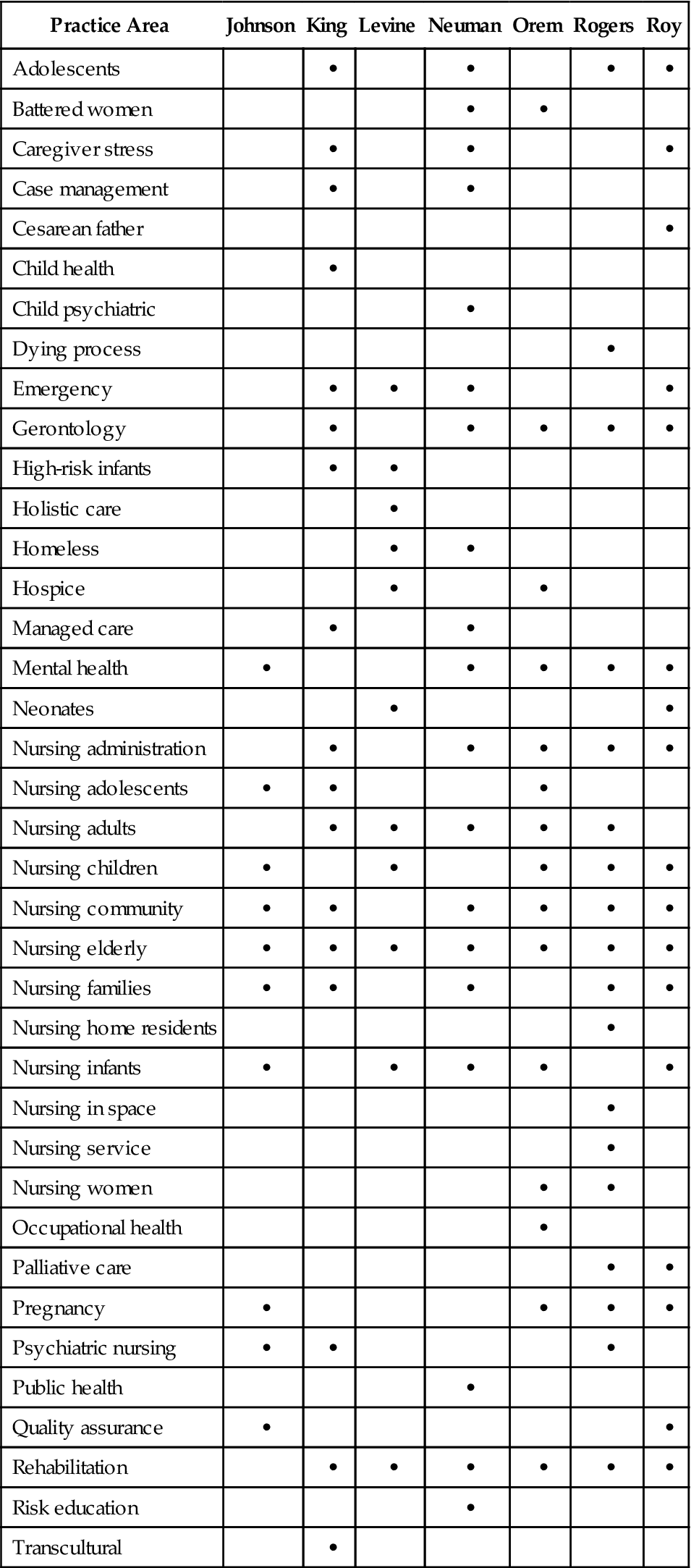

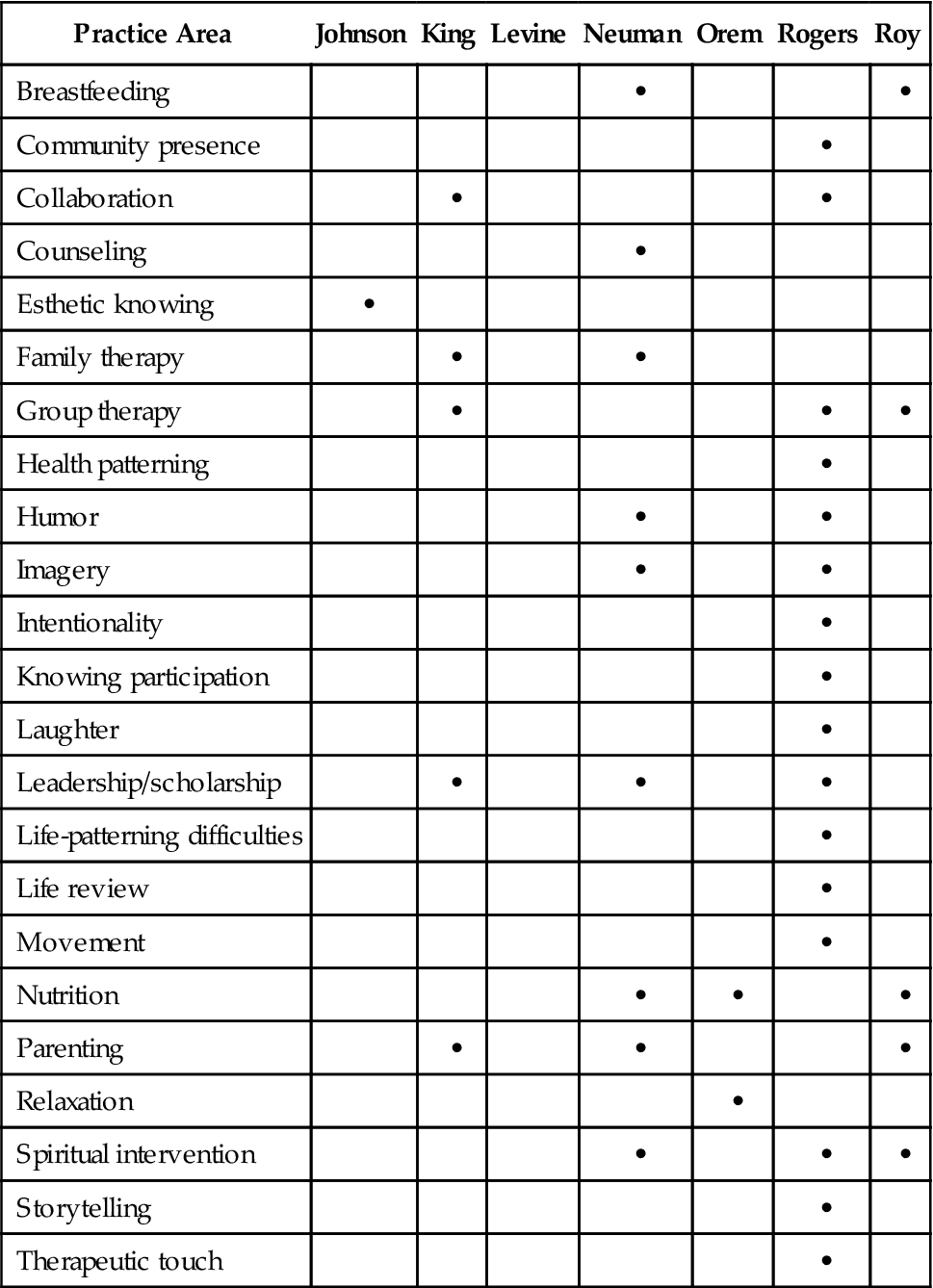

Based on a review of the nursing literature, this chapter begins with examples of practice areas where nursing models and their theories guide nursing. Although all three tables present the use of the nursing models and their theories in nursing practice, these applications are described by their authors in various ways: (1) in terms of the medical conditions; (2) in terms of nursing based on human development, areas of practice, type of care, and type of health; and (3) in terms of nursing interventions or the nursing role. (See the Bibliography for references to applications of each model cited in Tables 2-1, 2-2, and 2-3.) This chapter concludes with a review of thenursing models using the criteria for normal science set forth by Kuhn (1970) in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and a discussion of how the discipline of nursing has reached a period of normal science using the nursing models.

TABLE 2-1

Areas of Practice with Nursing Models Described in Terms of a Medical Conditions Focus

| Practice Area | Johnson | King | Levine | Neuman | Orem | Rogers | Roy |

| Acute care | • | ||||||

| Adolescent cancer | • | ||||||

| Adult diabetes | • | • | |||||

| AIDS management | • | • | • | • | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease | • | ||||||

| Ambulatory care | • | • | |||||

| Anxiety | • | • | • | • | |||

| Breast cancer | • | • | |||||

| Burns | • | ||||||

| Cancer | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Cancer pain management | • | ||||||

| Cancer-related fatigue | • | ||||||

| Cardiac disease | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Cardiomyopathy | • | ||||||

| Chronic inflammatory bowel disease | • | ||||||

| Chronic pain | • | • | • | ||||

| Chronic sorrow | • | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | • | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | • | ||||||

| Critical care | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Cystitis | • | ||||||

| Diabetes | • | • | • | ||||

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | • | ||||||

| Heart | • | • | |||||

| Hemodialysis | • | • | |||||

| Hypernatremia | • | ||||||

| Intensive care | • | • | • | • | |||

| Kawasaki disease | • | ||||||

| Leukemia | • | ||||||

| Long-term care | • | • | |||||

| Medical illness | • | • | • | ||||

| Menopause | • | • | |||||

| Neurofibromatosis | • | ||||||

| Obesity | • | • | |||||

| Oncology | • | • | • | • | |||

| Orthopedics | • | • | |||||

| Osteoporosis | • | ||||||

| Ostomy care | • | • | |||||

| Pediatrics | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Perioperative | • | • | • | • | |||

| Polio survivors | • | ||||||

| Postanesthesia | • | ||||||

| Postoperative | • | • | • | ||||

| Postpartum | • | ||||||

| Posttrauma | • | ||||||

| Preoperative adults | • | ||||||

| Preoperative anxiety | • | • | |||||

| Pressure ulcers | • | ||||||

| Renal disease | • | • | • | ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | • | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | • | ||||||

| Stroke | • | • | |||||

| Substance abuse | • | • | • | ||||

| Terminal illness | • | • | |||||

| Ventilator patient | • | ||||||

| Ventricular tachycardia | • | ||||||

| Wound healing | • |

TABLE 2-2

| Practice Area | Johnson | King | Levine | Neuman | Orem | Rogers | Roy |

| Adolescents | • | • | • | • | |||

| Battered women | • | • | |||||

| Caregiver stress | • | • | • | ||||

| Case management | • | • | |||||

| Cesarean father | • | ||||||

| Child health | • | ||||||

| Child psychiatric | • | ||||||

| Dying process | • | ||||||

| Emergency | • | • | • | • | |||

| Gerontology | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| High-risk infants | • | • | |||||

| Holistic care | • | ||||||

| Homeless | • | • | |||||

| Hospice | • | • | |||||

| Managed care | • | • | |||||

| Mental health | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Neonates | • | • | |||||

| Nursing administration | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nursing adolescents | • | • | • | ||||

| Nursing adults | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nursing children | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nursing community | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Nursing elderly | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Nursing families | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nursing home residents | • | ||||||

| Nursing infants | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nursing in space | • | ||||||

| Nursing service | • | ||||||

| Nursing women | • | • | |||||

| Occupational health | • | ||||||

| Palliative care | • | • | |||||

| Pregnancy | • | • | • | • | |||

| Psychiatric nursing | • | • | • | ||||

| Public health | • | ||||||

| Quality assurance | • | • | |||||

| Rehabilitation | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Risk education | • | ||||||

| Transcultural | • |

TABLE 2-3

Areas of Practice with Nursing Models with a Nursing Intervention or Role Focus

| Practice Area | Johnson | King | Levine | Neuman | Orem | Rogers | Roy |

| Breastfeeding | • | • | |||||

| Community presence | • | ||||||

| Collaboration | • | • | |||||

| Counseling | • | ||||||

| Esthetic knowing | • | ||||||

| Family therapy | • | • | |||||

| Group therapy | • | • | • | ||||

| Health patterning | • | ||||||

| Humor | • | • | |||||

| Imagery | • | • | |||||

| Intentionality | • | ||||||

| Knowing participation | • | ||||||

| Laughter | • | ||||||

| Leadership/scholarship | • | • | • | ||||

| Life-patterning difficulties | • | ||||||

| Life review | • | ||||||

| Movement | • | ||||||

| Nutrition | • | • | • | ||||

| Parenting | • | • | • | ||||

| Relaxation | • | ||||||

| Spiritual intervention | • | • | • | ||||

| Storytelling | • | ||||||

| Therapeutic touch | • |

The literature review makes it apparent that nurses describe their practice in several ways. Some describe nursing practice in terms of the medical conditions. This view focuses on the patient or area of care, as noted in Table 2-1. Examples ofthis focus are the nursing of cardiovascular patients or of intensive care patients. Several observations have been made about this focus (see Table 2-1). First, it represents the largest body of literature. Second, each model is represented within this focus. This large group of studies is surprising in light of the efforts of the past 40 years to move nursing beyond the medical view to a nursing perspective. However, this focus reflects the practice area, of the largest single group (54%) of practicing nurses, who, according to the Department of Labor Statistics (2010) provide acute care or illness care in hospitals.

Table 2-2 presents model and theory use in publications in which nurses describe their practice in terms of a developmental or life-span focus, a particulargroup in society, a type of care, or a type of health. Examples of this focus are nursing of children, homeless, holistic care, and child health. Table 2-2 reflects the second largest group of articles. Like Table 2-1, Table 2-2 represents articles based on all seven of the nursing models. Although Table 2-2 is large, it represents a grouping of several perspectives nurses use to describe their practice: nursing groups according to a developmental category, areas of practice, types of care, and types of health or health promotion.

Table 2-3 presents model and theory use in publications that focus on nursing intervention or nursing role. Examples of this focus are life review and counseling. This table is smaller than Tables 2-1 and 2-2 and differs in that not all of the nursing models are represented in Table 2-3. Certain nurses practicing from the perspective of nursing models seem to describe their practice in terms of nursing intervention or nursing role. It is noted that the specificity of the language in Rogerian science has created several unique categories in this focus. This is not surprising, considering the following:

• The development of a science calls for specific language.

• One would expect categories that are descriptive of the uniqueness of the nurse’s perspective.

The nursing categories in Tables 2-1, 2-2, and 2-3 can be considered in the context of Kuhn’s (1970) discussion of normal science. Paradigms (or nursing models) not only are frameworks to guide thinking about nursing and research but also the thought and action of practice. As such, their use by members of the profession produces knowledge that is evidence for practice as well as further research and theory development. Normal science verifies the growing maturity of a discipline as it moves beyond a knowledge development focus and focuses on knowledge use. Model-based nursing literature now reflects the characteristics of normal science. Middle-range theories and societies have been developed from nursing philosophies and theories in recent years that are beyond the scope of this chapter. The reader is referred to Part III of this text on expansion and Chapter 21 for a brief discussion of those developments.

In his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn (1970) examines the nature of scientific discovery. He defines normal science as “research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice” (p. 10). From this definition, Kuhn describes criteria that might be used for evaluation of a given paradigm (nursing model). The following are some of the characteristics of a model as it approaches normal science:

Thus Kuhn’s philosophy of science is useful to examine the science of the discipline of nursing. Three possible interpretations are presented.

Examination of the Models

Kuhn (1970) describes a paradigm that results in normal science as “an achievement sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of adherents away from competing modes of scientific activity” and as “leaving all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners to resolve” (p. 10). In the attempt to develop nursing science, theory from numerous modes of scientific activity including medicine, social and physical science, education, and even industrial management had been utilized (Wald & Leonard, 1964). However, it was not until the development of formal conceptual nursing models that nurses had “a systematic approach to nursing research, education, administration, and practice” (Fawcett, 1995, p. 5) that ultimately resulted in normal science for the discipline of nursing. Nursing theory continues to supply the foundation for knowledge development and generate evidence for practice (Bond, et al., 2011; Canavan, 2002; Colley, 2003; Im & Chang, 2012; Kikuchi, 2003; McCrae, 2011). Each of the models is reviewed with regard to Kuhn’s definition and criteria of normal science.

Johnson

First presented in its entirety in the 1980 edition of Conceptual Models for Nursing Practice (Riehl & Roy, 1980), the Behavioral System Model, developed by Dorothy Johnson, was a work in progress since 1959 (Fawcett, 1995). Beginning as a basis for development of nursing core content, Johnson’s work focuses on common human needs, care and comfort, and stress and tension reduction (Johnson, 1992). With its origins in Nightingale’s work, as well as in General System Theory (Fawcett, 2005), Johnson’s model attracted nurse scientists who linked her model with work from other disciplines to generate new theory (Fawcett, 1995). Use of the Behavioral System Model by educators, researchers, and practitioners across the country (Fawcett, 2005; Meleis, 2007) suggests that a significant number of nurses favor Johnson’s Behavioral System Model. There is currently no organized group of nurses who support the use of Johnson’s Behavioral System Model; however, Bonnie Holaday reports that nurses who use the model “stay in touch.” She has future plans for a Johnson model book (B. Holaday, personal communication, January 2012).

King

King (1964) first published work that would evolve into the General Systems Framework. Like many other theorists, King combined her own observations about nursing with knowledge from other disciplines and the theory from General System Theory to form a new conceptual framework for the discipline of nursing (King, 2006). With its focus on personal, interpersonal, and social systems, King’s conceptual framework and Theory of Goal Attainment that springs from it are widely used in nursing today (Alligood, 2010; Bond, et al., 2011; Sieloff & Frey, 2007). King’s emphasis on the role of the client as well as the nurse in the planning and implementation of health care has been noted as consistent with evolving philosophies of health care (Meleis, 2007). The King International Nursing Group (KING) provides an organization for support andcommunication among nurses using King’s General Systems Framework and Theory of Goal Attainment.

Levine

As is seen in Table 2-1, many nurse educators, researchers, and practitioners continue to rely on the medical model as their organizing framework. Levine very early perceived this as a problem for the development of nursing science and, in 1966, introduced a new paradigm to direct nursing away from the limitations of the medical view and provided nurses with a way to describe nursing care using a broader scientific view (Levine, 1966). Called the Conservation Model, Levine’s work provides an organizing framework that can be used in a variety of nursing settings to facilitate nursing education, research, and practice (Levine, 1988). Focusing on adaptation as a way to maintain the integrity and wholeness of the person, Levine’s work has attracted a large number of followers among nurse researchers, educators, administrators, and practitioners (Fawcett, 2005). Recent work with Levine’s Conservation Model in combination with the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA), Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), and Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) demonstrates the practical aspects of this model (Cox, 2003). There is evidence of current use of Levine’s work in the nursing literature (Delmore, 2006; Mefford & Alligood, 2011a,b). There is no Levine scholar organization.

Neuman

Like many of the nursing models, the Neuman Systems Model had its beginnings in an educational setting, where it was developed and implemented to facilitate advanced practice in graduate education. Developed around the same time as several other nursing models, Neuman first published a description of her model in 1972 (Neuman & Young, 1972). Influenced by a variety of nurse scholars, as well as knowledge from other disciplines, Neuman’s model incorporates, among others, the concepts of adaptation and client wholism, with a strong emphasis on stress in the client environment.

The Neuman Systems Model continued its evolution and development for more than 40 years. Nurse educators, researchers, administrators, and practitioners from around the world have made the Neuman Systems Model one of the most recognized and used of the nursing paradigms (Im & Chang, 2012; Neuman & Fawcett, 2011). The Neuman archives are located at the library of Neuman College in Aston, Pennsylvania. Nurses who have attained a graduate degree may join the Neuman Systems Model Trustees Group, Inc. (http://neumansystemsmodel.org/index.html).

Orem

A clinical nursing background in medical-surgical nursing of adults and children, combined with studies in a variety of disciplines and her own personal reflection, contributed to Orem’s development of the three-part theory of self-care (Orem, 2002). An early advocate of nursing conceptual models, Orem’s work first began to develop in the early 1970s. From the beginning, Orem balanced the task of defining the domain of nursing while providing a framework for nursing curriculadevelopment (Fawcett, 2005). Although a variety of nurse scholars and Orem herself continued to refine her work, the basic conceptual elements from 1970 remained unchanged (Orem, 2002).

Highly regarded globally for its usefulness in all aspects of nursing, Orem’s Self-Care Model continues to be the organizing framework of many nurse researchers, educators, scholars, administrators, and providers of patient care (Banfield, 2011; Berbiglia, 2011; Clarke, Allison, Berbiglia, et al., 2009; Horan, Doran, & Timmins, 2004; Orem & Taylor, 2011; Wilson, Mood, Risk, et al., 2003). Nurses who use the Orem model formed the International Orem Society for Nursing Science and Scholarship. This active world organization sponsors conferences and publications on the use and development of the Orem model available on the society website along with a list of schools of nursing that use the Orem model as an organizing framework.

Rogers

Of all the nursing models discussed in this chapter, the work of Martha Rogers perhaps best fits Kuhn’s (1970) description of a new paradigm as that which “forces scientists to investigate some part of nature in a detail and depth that would otherwise be unimaginable” (p. 24). With its focus on unitary human beings as the central phenomenon of nursing (Fawcett, 1995), the Science of Unitary Human Beings (Rogers, 1970, 1992) introduces a set of concepts to nursing science that were not suggested by other nursing models. Rejecting the idea of causality, Rogers’ work moved beyond the reciprocal interaction worldview of the other nursing models. Rather, Rogers’ work has a pandimensional view of people and their world (Rogers, 1992) consistent with the simultaneous action worldview (Fawcett, 1995).

Widely used by nurse researchers, educators, administrators, and clinical practitioners, the Science of Unitary Human Beings has a worldwide impact with nurses who use this truly unique paradigm for their practice. The Society for Rogerian Scholars (SRS) actively encourages the use of the Science of Unitary Human Beings through a program of scholarships, conferences, and publications that provides an avenue for work done in the model to be presented and discussed. The SRS manages a website and a refereed journal, Visions: The Journal of Rogerian Nursing Science, in its twentieth year of publication in 2012.

Roy

Beginning work on her model while she was a graduate student in the late 1960s, Sister Callista Roy drew the scientific basis for her Adaptation Model from both systems theory and adaptation-level theory (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Principles from these nonnursing disciplines were reconceptualized for implementation in nursing science (Meleis, 2007). In addition, threads from the work of other nurse scientists, particularly Johnson and Henderson (Meleis, 2007), contributed to what would become a new view of nursing. In a pattern seen in the development of many of the other scientific disciplines (Kuhn, 1970), Roy was able to synthesize contributions from other disciplines as well as works of early nurse scientists into the fabric of her own original thoughts. This resulted in a new paradigm for nursing science: the Roy Adaptation Model.

Formally published in 1970 (Roy, 1970), the Roy Adaptation Model was implemented as the basis of the curriculum at Mount St. Mary’s College, where the faculty has continued to work with Roy to develop and publish the elements of the model. The operationalization of the theory in the curriculum at Mount St. Mary’s College and the availability of literature and textbooks consistent with the model have resulted in its widespread adoption (Meleis, 2007). In addition, middle-range theory development continues from the model as demonstrated by Dunn’s work with chronic pain (Phillips, 2011).

Discussion

The concept of normal science introduced by Kuhn describes the acceptance of a new paradigm for use by a discipline. According to Kuhn (1970), normal science “means research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievements, achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice” (p. 10). The discipline of nursing moved toward normal science with widespread acceptance of the paradigm consisting of four concepts: person, health, environment, and nursing. However, these four concepts by themselves were not adequate for achievement of normal science. In a practice discipline such as nursing, the body of knowledge that is contained in the science must be at a level of abstraction that is suitable for application in practice.

The works of Johnson, King, Levine, Neuman, Orem, Rogers, and Roy, serving as frameworks for practice, education, and research, have provided this level of abstraction and, in doing so have resulted in a body of normal science for the discipline of nursing. Kuhn (1970) points out that “paradigms gain their status because they are more successful than their competitors in solving a few problems that the group as practitioners has come to recognize as acute” (p. 23). Affirmation of the seven models and the theories has developed through the use of them and is evidenced repeatedly in the current nursing literature. Research studies are conducted and reported and results are evidence for nursing education and client care (Barrett, 2002; Bond, et al., 2011; Donohue-Porter, et al., 2011; Im & Chang, 2012; McCrae, 2011). Im and Chang (2012) studied current trends in nursing theories from 2001 to 2010 and found that most of the theory-use-articles were based on four of the seven nursing models: Roy, Orem, Neuman, and Rogers. The theory utilization era is reflected in specific areas such as population-focused public health nursing (Bigbee & Issel, 2012), “people-centered” nursing with the elderly (Dewing, 2004), preadolescent empowerment (Frame, 2003), and curricula content to organize thinking (DeSimone, 2006; Donohue-Porter, et al., 2011).

There are several ways that Kuhn’s conception of normal science can be applied. First, it could be proposed that the discipline of nursing has one body of normal science with seven branches—the seven models. Although they are different in language, implementation, and research questions posed, each of the models is based on the four-concept metaparadigm and therefore has some commonalities. The models have their differences and all have contributed to what wecollectively call the body of nursing knowledge and, could be considered nursing normal science.

A second possibility for interpretation of Kuhn’s definition of normal science with regard to the discipline of nursing is to say that nursing has seven different bodies of normal science. Each of the seven nursing models has attracted a significant group of followers who utilize the models for practice, education, research, and development of nursing knowledge according to the specific views of nursing as evidenced by implementation of the models in health care institutions, schools of nursing, and textbooks. It is also evidenced by the fact that five of the seven models have professional organizations that have as their purpose to support and further the work in the models. In Kuhn’s (1970) words, those “whose research is based on shared paradigms are committed to the same rules and standards for scientific practice. That commitment and the apparent consensus it produces are prerequisites for normal science” (p. 11). Thus according to the criteria described by Kuhn for normal science, it is possible to accept the view that nursing does in fact have at least seven bodies of normal science.

The third and last viewpoint regarding the state of normal science within the discipline of nursing is that nursing has two bodies of normal science: one consisting of the knowledge produced from the work of Rogers Science of Unitary Human Beings and the other consisting of knowledge developed from the works of Johnson, King, Levine, Neuman, Orem, and Roy. Evidence for this viewpoint arises from the underlying worldview of the models, with Rogers’ model being based on the simultaneous action worldview and the remaining six models based on the reciprocal interaction worldview (Fawcett, 1995, 2005). A comparison of metaparadigm concept definitions from Rogers’ model with the other models demonstrates the differences, such as a human being viewed as a unitary irreducible, indivisible whole rather than as parts of a whole. A comparison of the implementation in practice, education, and research yields a similar conclusion. Although each of the six reciprocal interaction models is able to make unique contributions to the body of nursing knowledge, these contributions are similar in nature and thus can be viewed together as a body of normal science, separate and different from the knowledge developed from a simultaneous action view.

To summarize, a comparison of the body of nursing knowledge to the criteria that Kuhn proposes for normal science indicates that the discipline of nursing has, through use of the seven nursing models just examined, achieved the level of normal science. All of the models are accepted by groups of knowledge-building nurse scientists. The models all can and do provide bases for the practice of the discipline of nursing. Finally, all the models are open-ended; that is, they provide a framework for “further articulation and specification under new or more stringent conditions” (Kuhn, 1970, p. 23). Three interpretations of the structure of normal science in nursing have been used to answer the following basic question: “Has nursing achieved the level of normal science?” Each interpretation has led to the following answer: Yes; nursing conceptual models have led to the achievement of normal science in the discipline of nursing.