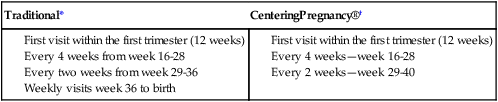

• Describe the process of confirming pregnancy and estimating the date of birth. • Summarize the physical, psychosocial, and behavioral changes that usually occur as the mother and other family members adapt to pregnancy. • Discuss the benefits of prenatal care and problems of accessibility for some women. • Outline the patterns of health care used to assess maternal and fetal health status at the initial and follow-up visits during pregnancy. • Identify the typical nursing assessments, diagnoses, interventions, and methods of evaluation in providing care for the pregnant woman. • Discuss education needed by pregnant women to understand physical discomforts related to pregnancy and to recognize signs and symptoms of potential complications. • Examine the impact of culture, age, parity, and number of fetuses on the response of the family to the pregnancy and on the prenatal care provided. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Assessment Videos: Chest wall, breast, abdomen/fundal height, fetal heart rate • Case Study: Second Trimester • Critical Thinking Exercise: Discomforts of Pregnancy • Critical Thinking Exercise: Teenage Pregnancy • Nursing Care Plan: Adolescent Pregnancy • Nursing Care Plan: Discomforts of Pregnancy and Warning Signs • Spanish Guidelines: Assessment of Respiratory Symptoms • Spanish Guidelines: Prenatal Interview Women may suspect pregnancy when they miss a menstrual period. Many women come to the first prenatal visit after a positive home pregnancy test; however, the clinical diagnosis of pregnancy before the second missed period is difficult in some women. Physical variations, obesity, or tumors, for example, may confuse even the experienced examiner. Accuracy is important, however, because emotional, social, medical, or legal consequences of an inaccurate diagnosis, either positive or negative, can be extremely serious. A correct date for the last (normal) menstrual period (LMP or LNMP) and for the date of intercourse and a basal body temperature (BBT) record are of great value in the accurate diagnosis of pregnancy (see Chapter 4). Great variability is possible in the subjective and objective signs and symptoms of pregnancy; therefore the diagnosis of pregnancy is often uncertain for a time. Many of the indicators of pregnancy are clinically useful in the diagnosis of pregnancy. They are classified as presumptive, probable, or positive (see Table 6-2). After the diagnosis of pregnancy, the woman’s first question usually concerns when she will give birth. This date has traditionally been termed the estimated date of confinement (EDC), although estimated date of delivery (EDD) is also used. However, the term estimated date of birth (EDB) promotes a more positive perception of both pregnancy and birth. Because the precise date of conception is generally unknown, several formulas can be used for calculating the EDB. None of these guides is infallible, but Nägele’s rule is reasonably accurate and is usually used (Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). Nägele’s rule is as follows: After determining the first day of the LMP, subtract 3 calendar months and add 7 days; or alternatively, add 7 days to the LMP and count forward 9 calendar months. Box 7-1 demonstrates use of Nägele’s rule. Nägele’s rule assumes that the woman has a 28-day menstrual cycle and that pregnancy occurred on the fourteenth day. Obtaining an accurate menstrual history is important as well in using this method of dating. Pregnancy is a maturational milestone that is often stressful but also rewarding as the woman prepares for a new level of caring and responsibility. Her self-concept changes in readiness for parenthood as she prepares for her new role. She moves gradually from being self-contained and independent to being committed to a lifelong concern for another human being. This growth requires mastery of certain developmental tasks: accepting the pregnancy, identifying with the role of mother, reordering the relationships between herself and her mother and between herself and her partner, establishing a relationship with the unborn child, and preparing for the birth experience (Lederman, 1996). The partner’s emotional support is an important factor in the successful accomplishment of these developmental tasks. Single women with limited support may have difficulty making this adaptation. The first step in adapting to the maternal role is accepting the idea of pregnancy and assimilating the pregnant state into the woman’s way of life. Mercer (1995) described this process as cognitive restructuring and credited Reva Rubin (1984) as the nurse theorist who pioneered our understanding of maternal role attainment. The degree of acceptance is reflected in the woman’s emotional responses. Many women are upset initially at finding themselves pregnant, especially if the pregnancy is unintended. Eventual acceptance of pregnancy parallels the growing acceptance of the reality of a child. However, do not equate nonacceptance of the pregnancy with rejection of the child; a woman may dislike being pregnant but feel love for the unborn child. Intense feelings of ambivalence that persist through the third trimester may indicate an unresolved conflict with the motherhood role (Mercer, 1995). After the birth of a healthy child, memories of these ambivalent feelings are usually dismissed. If the child is born with a defect, however, a woman may look back at the times when she did not want the pregnancy and feel intensely guilty. She may believe that her ambivalence caused the birth defect. She will then need assurance that her feelings were not responsible for the problem. The woman’s own relationship with her mother is significant in adaptation to pregnancy and motherhood. Important components in the pregnant woman’s relationship with her mother are the mother’s availability (past and present), her reactions to the daughter’s pregnancy, respect for her daughter’s autonomy, and the willingness to reminisce (Mercer, 1995). The mother’s reaction to the daughter’s pregnancy signifies her acceptance of the grandchild and of her daughter. If the mother is supportive, the daughter has an opportunity to discuss pregnancy, labor, and her feelings with a knowledgeable and accepting woman (Fig. 7-1). Reminiscing about the pregnant woman’s early childhood and sharing the prospective grandmother’s account of her childbirth experience help the daughter to anticipate and prepare for labor and birth. The marital or committed relationship is not static but evolves over time. The addition of a child changes forever the nature of the bond between partners. This is often a time when couples grow closer, and the pregnancy has a maturing effect on the partners’ relationship as they assume new roles and discover new aspects of one another. Partners who trust and support each other are able to share mutual-dependency needs (Mercer, 1995). As pregnancy progresses, changes in body shape, body image, and levels of discomfort influence both partners’ desire for sexual expression. During the first trimester, the woman’s sexual desire often decreases, especially if she has breast tenderness, nausea, fatigue, or sleepiness. As she progresses into the second trimester, however, her sense of well-being combined with the increased pelvic congestion that occurs at this time may increase her desire for sexual release. In the third trimester, somatic complaints and physical bulkiness increase physical discomfort and again diminish interest in sex. As a woman’s pregnancy progresses, her enlarging gravid abdomen may limit the use of the man-on-top position for intercourse. Therefore other positions (e.g., side to side or the woman on top) may allow intercourse and minimize pressure on the woman’s abdomen (Westheimer & Lopater, 2005). Emotional attachment—feelings of being tied by affection or love—begins during the prenatal period as women use fantasizing and daydreaming to prepare themselves for motherhood (Rubin, 1975). They think of themselves as mothers and imagine maternal qualities they would like to possess. Expectant parents desire to be warm, loving, and close to their child. They try to anticipate changes that the child will bring in their lives and wonder how they will react to noise, disorder, reduced freedom, and caregiving activities. The mother-child relationship progresses through pregnancy as a developmental process that unfolds in three phases. Although the mother alone experiences the child within, both parents and siblings believe the unborn child responds in a very individualized, personal manner. Family members may interact a great deal with the unborn child by talking to the fetus and stroking the mother’s abdomen, especially when the fetus shifts position (Fig. 7-2). The fetus may even have a nickname used by family members. Anxiety can arise from concern about a safe passage for herself and her child during the birth process (Mercer, 1995; Rubin, 1975). Some women do not express this concern overtly, but they give cues to the nurse by making plans for care of the new baby and other children in case “anything should happen.” These feelings persist despite statistical evidence about the safe outcome of pregnancy for mothers and their infants. Many women fear the pain of childbirth or mutilation because they do not understand anatomy and the birth process. Education can alleviate many of these fears. Women also express concern over what behaviors are appropriate during the birth process and whether caregivers will accept them and their actions. The ways fathers adjust to the parental role has been the subject of considerable research. In older societies the man enacted the ritual couvade; that is, he behaved in specific ways and respected taboos associated with pregnancy and giving birth so the man’s new status was recognized and endorsed. Now, some men experience pregnancy-like symptoms, such as nausea, weight gain, and other physical symptoms. This phenomenon is known as the couvade syndrome. Changing cultural and professional attitudes have encouraged fathers’ participation in the birth experience in the last 30 years (Fig. 7-3). The man’s emotional responses to becoming a father, his concerns, and his informational needs change during the course of pregnancy. Phases of the developmental pattern become apparent. May (1982) described three phases characterizing the developmental tasks experienced by the expectant father: • The announcement phase may last from a few hours to a few weeks. The developmental task is to accept the biologic fact of pregnancy. Men react to the confirmation of pregnancy with joy or sadness, depending on whether the pregnancy is desired or unplanned or unwanted. Ambivalence in the early stages of pregnancy is common. • If pregnancy is unplanned or unwanted, some men find the alterations in life plans and lifestyles difficult to accept. Some men engage in extramarital affairs for the first time during their partner’s pregnancy. Others batter their wives for the first time or escalate the frequency of battering episodes (Krieger, 2008). Chapter 2 provides information about violence against women and offers guidance on assessment and intervention. • The second phase, the moratorium phase, is the period when he adjusts to the reality of pregnancy. The developmental task is to accept the pregnancy. Men appear to put conscious thought of the pregnancy aside for a time. They become more introspective and engage in many discussions about their philosophy of life, religion, childbearing, and childrearing practices and their relationships with family members, particularly with their father. Depending on the man’s readiness for the pregnancy, this phase may be relatively short or persist until the last trimester. • The third phase, the focusing phase, begins in the last trimester and is characterized by the father’s active involvement in both the pregnancy and his relationship with his child. The developmental task is to negotiate with his partner the role he is to play in labor and to prepare for parenthood. In this phase the man concentrates on his experience of the pregnancy and begins to think of himself as a father. A mother with other children must devote time and effort to reorganizing her relationships with them. She needs to prepare siblings for the birth of the child (Fig. 7-4 and Box 7-2) and begin the process of role transition in the family by including the children in the pregnancy and being sympathetic to older children’s concerns about losing their places in the family hierarchy. No child willingly gives up a familiar position. By age 3 or 4 years, children like to hear the story of their own beginning and to hear how their development compares with that of the present pregnancy. They like to listen to the fetal heartbeat and feel the baby moving in utero (see Fig. 7-2). Sometimes they worry about how the baby is being fed and what it wears. In addition, the grandparent is the historian who transmits the family history, a resource who shares knowledge based on experience, a role model, and a support person. The grandparent’s presence and support can strengthen family systems by widening the circle of support and nurturance (Fig. 7-5). Advances have occurred in the number of women in the United States who receive adequate prenatal care. In 2005, almost 84% of all women received care in the first trimester. African-American, Hispanic, and Native-American women were two times as likely to get late prenatal care or no care at all than Caucasian women (Martin et al., 2008). Although women of middle or high socioeconomic status routinely seek prenatal care, women living in poverty or who lack health insurance are not always able to use public medical services or gain access to private care. Lack of culturally sensitive care providers and barriers in communication resulting from differences in language also interfere with access to care (Darby, 2007). Similarly, immigrant women who come from cultures in which prenatal care is not emphasized may not know to seek routine prenatal care. Birth outcomes in these populations are less positive, with higher rates of maternal and fetal or newborn complications. Problems with low birth weight (LBW; less than 2500 g) and infant mortality have in particular been associated with lack of adequate prenatal care. Barriers to obtaining health care during pregnancy include lack of transportation, unpleasant clinic facilities or procedures, inconvenient clinic hours, child care problems and personal attitudes (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2006; Daniels, Noe, & Mayberry, 2006; Johnson, Hatcher, et al., 2007). The increasing use of advanced practice nurses in collaborative practice with physicians can help improve the availability and accessibility of prenatal care. A regular schedule of home visiting by nurses during pregnancy has also proven effective (Dawley & Beam, 2005). The current model for provision of prenatal care has been used for more than a century. The initial visit usually occurs in the first trimester, with visits every four weeks through week 28 of pregnancy. Thereafter, visits are scheduled every 2 weeks until week 36 and then every week until birth (American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [2007]) (Box 7-3). Research supports a model of fewer prenatal visits, and in some practices there is a growing tendency to have fewer visits with women who are at low risk for complications (Villar, Carroli, Khan-Neelofur, Piaggio, & Gulmezoglu, 2001; Walker, McCully, & Vest, 2001). CenteringPregnancy® is a care model that is gaining in popularity. This model is one of group prenatal care in which authority is shifted from the provider to the woman and other women who have similar due dates. The model creates an atmosphere that facilitates learning, encourages discussion, and develops mutual support. Most care takes place in the group setting after the first visit and continues for 10 2-hour sessions scheduled throughout the pregnancy (Moos, 2006) (see Box 7-3). At each meeting the first 30 minutes is spent in completing assessments (by self and by provider), and the rest of the time is spent in group discussion of specific issues such as discomforts of pregnancy and preparation for labor and birth. Families and partners are encourage to participate (Massey, Rising, & Ickovics, 2006; Reid, 2007). Prenatal care is ideally a multidisciplinary activity in which nurses work with physicians or midwives, nutritionists, social workers, and others. Collaboration among these individuals is necessary to provide holistic care. The case management model, which makes use of care maps and critical pathways, is one system that promotes comprehensive care with limited overlap in services. To emphasize the nursing role, care management for the initial visit and follow-up visits is organized around the central elements of the nursing process: assessment, nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes, plan of care and interventions, and evaluation (see Nursing Process box). Women who have chronic or handicapping conditions often forget to mention them during the initial assessment because they have become so adapted to them. Special shoes or a limp may indicate the existence of a pelvic structural defect, which is an important consideration in pregnant women. The nurse who observes these special characteristics and inquires about them sensitively can obtain individualized data that will provide the basis for a comprehensive nursing care plan (Smeltzer, 2007). The woman’s nutritional history is an important component of the prenatal history because her nutritional status has a direct effect on the growth and development of the fetus. A dietary assessment will reveal special diet practices, food allergies, eating behaviors, the practice of pica, and other factors related to her nutritional status. Pregnant women are usually motivated to learn about good nutrition and respond well to nutritional advice generated by this assessment. (See Chapter 8 for further discussion.) A woman’s past and present use of legal (over-the-counter [OTC] and prescription medications, herbal preparations, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine) and illegal (marijuana, cocaine, heroin) drugs is assessed. This assessment is needed because many substances cross the placenta and may harm the developing fetus. Periodic urine toxicologic screening tests are often recommended during the pregnancies of women who have a history of illegal drug use. In some states of the United States, these test results have been used for criminal prosecution, which violates the patient-provider relationship and ethical responsibilities to the patient (Harris & Paltrow, 2003). To preserve constitutional rights and the ethical patient-provider relationship, drug-testing policies should encourage open communication between patient and physician, emphasize the availability of treatment options, and advocate for the health of woman and child. • Is this pregnancy planned or not, wanted or not? • Is the woman pleased, displeased, accepting, or nonaccepting? • What problems related to finances, career, or living accommodations will occur as a result of the pregnancy? Determine the family support system by asking: • What primary support is available to her? • Are changes needed to promote adequate support? • What are the existing relationships among the mother, father or partner, siblings, and in-laws? • What preparations is she making for her care and that of dependent family members during labor and for the care of the infant after birth? • Does she need financial, educational, or other support from the community? • What are the woman’s ideas about childbearing, her expectations of the infant’s behavior, and her outlook on life and the female role? Other such questions to ask include the following: • What does the woman think it will be like to have a baby in the home? • How is her life going to change by having a baby? All women should be assessed for a history or risk of physical abuse, particularly because the likelihood of abuse increases during pregnancy. Although a woman’s appearance or behavior may suggest the possibility of abuse, do not limit questioning to only those women who fit the supposed profile of the battered woman. Identification of abuse and immediate clinical intervention that includes information about safety will help prevent future abuse and increase the safety and well-being of the woman and her infant (Krieger, 2008) (see Fig. 2-11). Battering and pregnancy in teenagers constitute a particularly difficult situation. Some adolescents are trapped in the abusive relationship because of their inexperience. Many professionals and the adolescents themselves ignore the violence because it may not be believable, because relationships are transient, and because the jealous and controlling behavior is interpreted as love and devotion. Routine screening for abuse and sexual assault is recommended for pregnant adolescents. (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2009). Because pregnancy in young adolescent girls is commonly the result of sexual abuse, assess the desire to maintain the pregnancy. During this portion of the interview, ask the woman to identify and describe preexisting or concurrent problems in any of the body systems. Assess her mental status as well. Question the woman about physical symptoms she has experienced, such as shortness of breath or pain. Pregnancy affects and is affected by all body systems; therefore information on the present status of the body systems is important in planning care. For each sign or symptom described, obtain the following additional data: body location, quality, quantity, chronology, aggravating or alleviating factors, and associated manifestations (onset, character, course) (Seidel, Ball, Dains, & Benedict, 2006). Each examiner develops a routine for proceeding with the physical examination; most choose the head-to-toe progression. The examiner evaluates heart and lung sounds, and examines extremities. Distribution, amount, and quality of body hair are of particular importance because the findings reflect nutritional status, endocrine function, and attention to hygiene. The examiner assesses the thyroid gland thoroughly. The height of the fundus is noted if the first examination is performed after the first trimester of pregnancy. During the examination the examiner needs to remain alert to cues that indicate a potential threatening condition, such as supine hypotension—low BP that occurs while the woman is lying on her back, causing feelings of faintness. See Chapter 2 for a detailed description of the physical examination. Specimens are collected at the initial visit so that the cause of any abnormal findings can be treated. Blood is drawn for a variety of tests (Table 7-1). A sickle cell screen is recommended for women of African, Asian, or Middle Eastern descent, and testing for antibody to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is strongly recommended for all pregnant women (Box 7-4). In addition, pregnant women and fathers with a family history of cystic fibrosis and of Caucasian ethnicity may want to have blood drawn for testing to determine if they are a cystic fibrosis carrier (Fries, Bashford, & Nunes (2005). Urine specimens are usually tested by dipstick; culture and sensitivity tests are ordered as necessary. During the pelvic examination, cervical and vaginal smears may be obtained for cytologic studies and for diagnosis of infection (e.g., Chlamydia, gonorrhea, group B Streptococcus [GBS]).

Nursing Care of the Family during Pregnancy

Web Resources

![]()

Diagnosis of Pregnancy

Signs and Symptoms

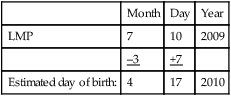

Estimating Date of Birth

Adaptation to Pregnancy

Maternal Adaptation

Accepting the Pregnancy

Reordering personal relationships

Establishing a relationship with the fetus

Preparing for childbirth

Paternal Adaptation

Accepting the pregnancy

Sibling Adaptation

Grandparent Adaptation

Care Management

Initial Assessment

Medical history

Nutritional history

History of drug and herbal preparations use

Social, experiential, and occupational history

History of physical abuse

Review of systems

Physical examination

Laboratory tests

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Care of the Family during Pregnancy

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access