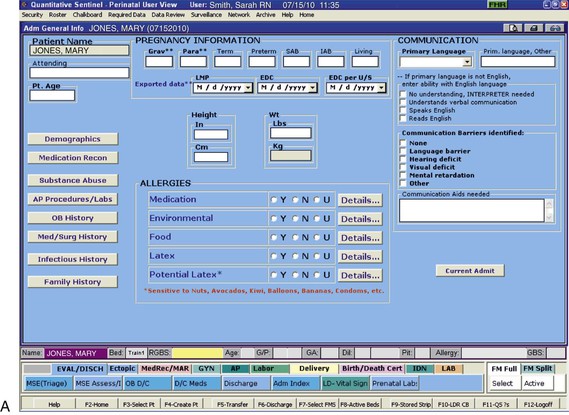

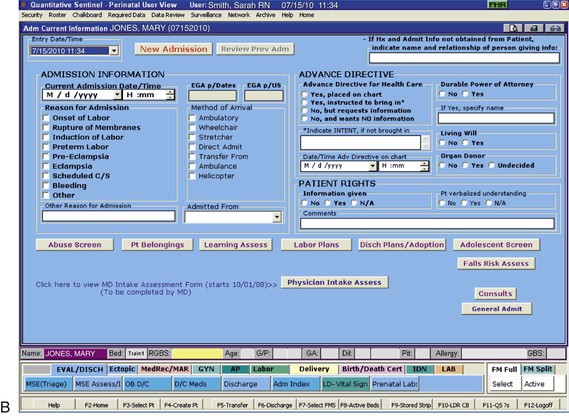

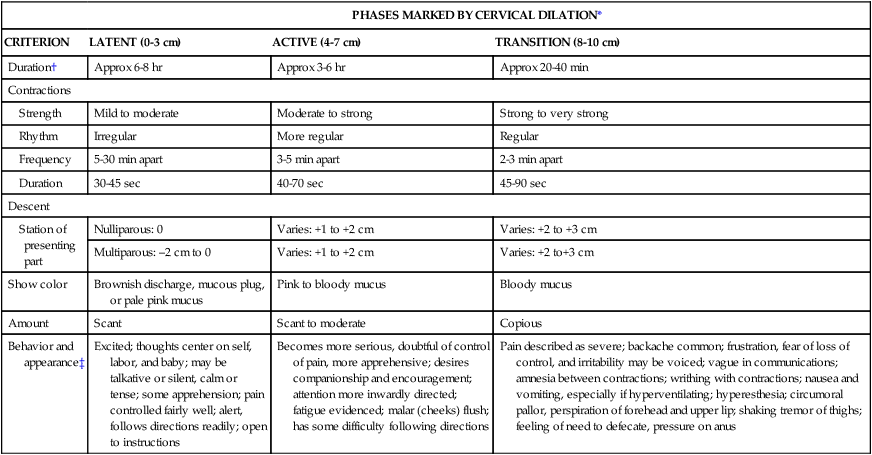

• Review the factors included in the initial assessment of the woman in labor. • Describe the ongoing assessment of maternal progress during the first, second, third, and fourth stages of labor. • Recognize the physical and psychosocial findings indicative of maternal progress during labor. • Identify signs of developing complications during labor and birth. • Identify nursing interventions for each stage of labor and birth. • Examine the influence of cultural and religious beliefs and practices on the process of labor and birth. • Describe the role and responsibilities of the nurse during an emergency childbirth. • Discuss how the nurse can increase the use of evidence-based practices in caring for women during labor and birth. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Assessment Video: Leopold Maneuvers • Case Study: First Stage of Labor • Case Study: Second/Third Stages of Labor • Critical Thinking Exercise: Positioning during Labor • Nursing Care Plan: Labor and Birth • Spanish Guidelines: Care during Labor • Spanish Guidelines: Labor Assessment Assessment begins at the first contact with the woman, whether by telephone or in person. Many women still call the hospital or birthing center first for validation that coming in for evaluation or admission is acceptable. Many hospitals, however, now discourage this practice because of concerns related to legal liability. Nurses are often instructed to tell patients who call with questions “You need to call your primary care provider,” or “If you think you need to be checked, come to the hospital.” If advice is given over the telephone, it must be carefully documented in the patient’s record or in a telephone triage logbook on the unit (Gilbert, 2007). Some pregnant women call the primary health care provider or come to the hospital while in false labor or early in the latent phase of the first stage of labor. Some feel discouraged after learning that the contractions that feel so strong and regular are not true contractions because they are not causing cervical dilation or are still not strong or frequent enough for admission. During the third trimester of pregnancy, women should be instructed regarding the stages of labor and the signs indicating its onset. They should be informed of the possibility that they will not be admitted if they are 3 cm or less dilated (see Teaching Guidelines box). When the woman arrives at the perinatal unit, assessment is the top priority (Fig. 12-1). The nurse first performs a screening assessment by using the techniques of interview and physical assessment and reviews the laboratory and diagnostic test findings to determine the health status of the woman and her fetus and the progress of her labor. The nurse also notifies the primary health care provider, and if the woman is admitted, a detailed systems assessment is performed. Most hospitals have specific forms, whether paper or electronic, that are used to obtain important assessment information when a woman in labor is being evaluated or admitted (Fig. 12-2). More and more hospitals now use an electronic medical record in which almost all charting is done on computer. Sources of data include the prenatal record, the initial interview, physical examination to determine baseline physiologic parameters, laboratory and diagnostic test results, expressed psychosocial and cultural factors, and the clinical evaluation of labor status. Thoroughly review her prenatal record. Take note of her obstetric and pregnancy history, which includes gravidity, parity, and problems such as history of vaginal bleeding, gestational hypertension, anemia, gestational diabetes, infections (e.g., bacterial, viral, or sexually transmitted), and immunodeficiency status. Confirm the expected date of birth (EDB). Other important data found in the prenatal record include patterns of maternal weight gain, physiologic measurements such as maternal vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, pulse, respirations), fundal height, baseline fetal heart rate (FHR), and laboratory and diagnostic test results. See Table 7-1 for a list of common prenatal laboratory tests. Common diagnostic and fetal assessment tests performed prenatally include amniocentesis, nonstress test (NST), biophysical profile (BPP), and ultrasound examination. See Chapter 19 for more information. • Time and onset of contractions and progress in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity • Location and character of discomfort from contractions (e.g., back pain, suprapubic discomfort) • Persistence of contractions despite changes in maternal position and activity (e.g., walking or lying down) • Presence and character of vaginal discharge or show • The status of amniotic membranes, such as a gush or seepage of fluid ([spontaneous] rupture of membranes [S] [ROM]). If a discharge has occurred that may be amniotic fluid, ask her the date and time she first noticed the fluid and its characteristics (e.g., amount, color, unusual odor). In many instances, a sterile speculum examination and a Nitrazine (pH) test or fern test can confirm that the membranes are ruptured (see Procedure box). The nurse obtains any information not found in the prenatal record during the admission assessment. Pertinent data include the birth plan (Box 12-1), the choice of infant feeding method, the type of pain management preferred, and the name of the pediatric health care provider. Obtain a patient profile that identifies the woman’s preparation for childbirth, the support person or family members desired during childbirth and their availability, and ethnic or cultural expectations and needs. Determine the woman’s use of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco before or during pregnancy. The woman’s general appearance and behavior (and that of her partner) provide valuable clues to the type of supportive care she will need. However, keep in mind that general appearance and behavior may vary, depending on the stage and phase of labor (Table 12-1 and Box 12-2). TABLE 12-1 Expected Maternal Progress in First Stage of Labor *In the nullipara, effacement is often complete before dilation begins; in the multipara, effacement occurs simultaneously with dilation. †Duration of each phase is influenced by such factors as parity, maternal emotions, position, level of activity, and fetal size, presentation, and position. For example, the labor of a nullipara tends to last longer, on average, than the labor of a multipara. Women who ambulate and assume upright positions or change positions frequently during labor tend to experience a shorter first stage. Descent is often prolonged in breech presentations and occiput posterior positions. ‡Women who have epidural analgesia for pain relief may not demonstrate some of these behaviors. Discuss the feelings a woman has about her pregnancy and fears regarding childbirth. This discussion is especially important if the woman is a primigravida who has not attended childbirth classes or is a multiparous woman who has had a previous negative childbirth experience. Women in labor usually have a variety of concerns that they will voice if asked but rarely volunteer. Major fears and concerns relate to the process and effects of childbirth, maternal and fetal well-being, and the attitude and actions of the health care staff. Unresolved fears increase a woman’s stress and can inhibit the process of labor as a result of the inhibiting effects of catecholamines associated with the stress response on uterine contractions (Zwelling, Johnson, & Allen, 2006). As the population in the United States and Canada becomes more diverse, noting the woman’s ethnic or cultural and religious background is increasingly important so as to anticipate nursing interventions to add or eliminate from the individualized plan of care (Fig. 12-3). Nurses should be committed to providing culturally sensitive care and to developing an appreciation and respect for cultural diversity (Callister, 2005). Encourage the woman to request specific caregiving behaviors and practices that are important to her. If a special request contradicts usual practices in that setting, then the woman or the nurse can ask the woman’s primary health care provider to write an order to accommodate the special request. For example, in many cultures, having a male caregiver examine a pregnant woman would be unacceptable. In some cultures, taking the placenta home is traditional; in other cultures the woman has only certain nourishments during labor. Some women believe that cutting the body, as with an episiotomy, allows the spirit to leave the body and that rupturing the membranes prolongs, not shortens, labor. The nurse should explain the rationale for required care measures carefully (see Cultural Considerations box). Ideally, a bilingual nurse will care for the woman. Alternatively, contact a hospital employee or volunteer interpreter for assistance (see Box 1-7). Ideally, the interpreter is from the woman’s culture. For some women a female interpreter is more acceptable than a male interpreter. If no one in the hospital is able to interpret, call a service so that interpretation can take place over the telephone. Even when the nurse has limited ability to communicate verbally with the woman, in most instances the woman appreciates the nurse’s efforts to do so. Speaking slowly and avoiding complex words and medical terms can help a woman and her partner to understand.

Nursing Care of the Family during Labor and Birth

Web Resources

![]()

First Stage of Labor

Care Management

Assessment

Prenatal data

Interview

Psychosocial factors

PHASES MARKED BY CERVICAL DILATION*

CRITERION

LATENT (0-3 cm)

ACTIVE (4-7 cm)

TRANSITION (8-10 cm)

Duration†

Approx 6-8 hr

Approx 3-6 hr

Approx 20-40 min

Contractions

Strength

Mild to moderate

Moderate to strong

Strong to very strong

Rhythm

Irregular

More regular

Regular

Frequency

5-30 min apart

3-5 min apart

2-3 min apart

Duration

30-45 sec

40-70 sec

45-90 sec

Descent

Station of presenting part

Nulliparous: 0

Varies: +1 to +2 cm

Varies: +2 to +3 cm

Multiparous: –2 cm to 0

Varies: +1 to +2 cm

Varies: +2 to+3 cm

Show color

Brownish discharge, mucous plug, or pale pink mucus

Pink to bloody mucus

Bloody mucus

Amount

Scant

Scant to moderate

Copious

Behavior and appearance‡

Excited; thoughts center on self, labor, and baby; may be talkative or silent, calm or tense; some apprehension; pain controlled fairly well; alert, follows directions readily; open to instructions

Becomes more serious, doubtful of control of pain, more apprehensive; desires companionship and encouragement; attention more inwardly directed; fatigue evidenced; malar (cheeks) flush; has some difficulty following directions

Pain described as severe; backache common; frustration, fear of loss of control, and irritability may be voiced; vague in communications; amnesia between contractions; writhing with contractions; nausea and vomiting, especially if hyperventilating; hyperesthesia; circumoral pallor, perspiration of forehead and upper lip; shaking tremor of thighs; feeling of need to defecate, pressure on anus

Stress in labor

Cultural factors

The non–English-speaking woman in labor.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Care of the Family during Labor and Birth

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access