Newman’s Theory of Health as Expanding Consciousness in Nursing Practice

Janet Witucki Brown and Martha Raile Alligood

Nurses practicing within this perspective experience the joy of participating in the transformation of others and find that their own lives are enhanced and transformed in the process of the dialogue.

History and Background

The first published version of Newman’s theory appeared in her book Theory Development in Nursing (Newman, 1979). In this early writing, Newman presented a viewpoint of health as a dialectic fusion of disease and nondisease, thus encompassing disease as a meaningful aspect of the totality of life experience. This viewpoint of health was developed as a result of two influences: (1) Newman’s early experiences of her mother’s 9-year struggle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, during which time Newman came to realize that an individual may be whole even though illness is present; and (2) Newman’s exposure to Martha Rogers’ work, which assisted her in conceptualizing health and illness as a single unitary process (Newman, 1986).

Evolution of the conceptualization of Health as Expanding Consciousness (HEC) was influenced theoretically by several sources. Bentov’s (1977) explanation of the evolution of consciousness, Moss’s (1981) view of love as the highest level of consciousness, Bohm’s (1980) theory of implicate order, de Chardin’s (1959) belief that consciousness continues to develop beyond physical life, and Young’s (1976) stages of human development all contributed to Newman’s ability to synthesize her thoughts and experiences into a cohesive and meaningful theory (Newman, 1994a). The Theory of HEC evolved from a synthesis of these theoretical influences with Newman’s own life experiences and thoughts.

Early application of this theory isolated and manipulated the theory concepts of space, time, and movement. Newman explored effects of changes in rates of walking on time perception in two studies (Newman, 1972, 1976) and the relationship between age, movement, and time perception of elders in another study (Newman, 1982). As work and research with the developing theory progressed, Newman discovered that research involving a person’s pattern identification and the sharing of patterns with a person was nursing practice and that the research produced a therapeutic outcome. She noted “our participation in the process made a difference in our own lives. We suspected that what we were doing in the name of research was nursing practice” (Newman, 1990a, p. 37). Research began to be viewed as praxis. Theory, research, and practice are seen as one inseparable process (Newman, 1990a,d). The professional nurse is viewed as a therapeutic partner who joins with the client in the search for pattern with its accompanying understanding and impetus for growth (Newman, 1987a).

Newman (1990a) developed a practice methodology of pattern identification and research/practice process. This method reveals sequential patterns of persons’ lives and facilitates recognition and insight into patterns. Authentic involvement of the nurse-researcher in the movement toward higher consciousness is emphasized. The theory and methodology have provided a basis for research/practice in a variety of clinical settings with diverse client populations for exploring and understanding the experience of illness to individuals and families.

The theory research or practice application has been used with cancer patients (Barron, 2005; Endo, 1998; Endo, Nitta, Inayoshi, et al., 2000; Kiser-Larsen, 2002; Newman, 1995b; Roux, Bush, & Dingley, 2001); elderly women with chronic disease (Kluge, Tang, Glick, et al., 2012); black-Caribbean women (Peters-Lewis, 2006); menopausal women (Musker, 2005); persons with coronary heart disease (Newman & Moch, 1991); dementia (Ruka, 2005); human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) (Lamendola & Newman, 1994); multiple sclerosis (Neill, 2004); rheumatoid arthritis (Neill, 2002); and spousal caregivers (Brown, 2011; Brown & Alligood, 2004; Brown, Chen, Mitchell, et al., 2007). Other groups that have been studied with the Theory of HEC include adolescent males incarcerated for murder (Pharris, 2002); depressed adolescents (Kweon & Lee, 2009); persons living with chronic skin wounds (Rosa, 2006); individuals with hepatitis C (MacNeil, 2012; Thomas, 2002); midlife women (Picard, 2000); and women who lose weight and successfully maintain weight loss (Berry, 2004). Further studies include family members following the death of a child (Picard, 2002; Weed, 2004); the transformative experience of Japanese and Canadian primary family caregivers of relatives with schizophrenia (Yamashita, 1998, 1999); and patterns of families with special-needs children (Falkenstern, 2003; Tommet, 2003).

Pharris (2002, 2005) advocated application of the theory to individuals, families, and communities. The theory has been applied to nursing management at Carondolet St. Mary’s Hospital and Health Center in Tucson, Arizona (Newman, Lamb, & Michaels, 1991). Flannagan (2005) and colleagues (Flannagan, Farrell, Zelano, et al., 2000) developed a Preadmission Nursing Practice Model (PNPM) based on the theory. In further educational use, Picard and Mariolos (2002) reported using the theory teaching psychiatric nursing students. Recent global useof Newman’s theory is reflected in publications by nurses worldwide (Dyess, 2011; Kluge, et al., 2012; Kweon & Lee, 2009; MacNeil, 2012; Rosa & Suong, 2009; Yang, Xiong, Vang, et al., 2009) to list a few.

Overview of Newman’s Theory of Health as Expanding Consciousness

In the early development of the theory Newman asserted that the phenomena of inquiry for nursing should be parameters of human wholeness and that there were characteristics of people that identified the whole (Newman, 1979). Time, space, and movement were identified by Newman as dimensions of pattern and consciousness and have been synthesized as the theory evolved to include the major concepts of health, consciousness, and patterns of movement and space-time.

Health

Newman’s theory proposes a view of health as a unidirectional, unitary process of development (Newman, 1991). She acknowledges that Rogers’ (1970) Science of Unitary Human Beings was a major influence in development of the Theory of HEC. In Newman’s theory, health is an expansion of consciousness that is defined as the informational capacity of the system and is seen as the ability of the person to interact with the environment (Newman, 1994a). Disease is a meaningful reflection of the whole and, as such, is viewed as a manifestation of health. Disease and nondisease are not separate entities but are dialectically fused into health as a pattern of the whole. According to Newman (1999), “Health is the pattern of the whole, and wholeness is. One cannot lose it or gain it” (p. 228). Disruptions in patterns of human beings, such as disease or catastrophic life events, often become catalysts that potentiate unfolding of life processes that individuals naturally seek, thereby facilitating movement from one pattern of consciousness to another and transformation into order at a higher level—or expanded consciousness (Newman, 1997).

Consciousness

Consciousness is defined in the theory as the informational capacity of the system (human beings) or the system’s ability to interact with the environment (Newman, 1990a). Newman asserts that an understanding of her definition of consciousness is essential to understanding the theory. Consciousness includes not only cognitive and affective awareness but also the “interconnectedness of the entire living system, which includes physiochemical maintenance and growth processes as well as the immune system” (Newman, 1990a, p. 38). Consciousness is further conceptualized as co-extensive in the universe and as the essence of all creation. Interaction, then, occurs openly, constantly, and instantaneously throughout the entire spectrum of consciousness (Newman, 1994a). The person does not just possess consciousness but is consciousness, as is all matter. The highest level of consciousness is absolute consciousness, which Newman equates with love that “embraces all experience equally and unconditionally” (Newman, 1994a, p. 48).

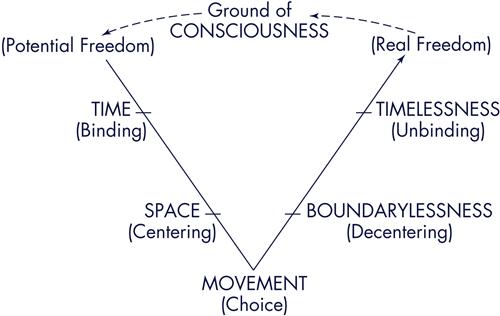

Movement through levels of consciousness occurs continuously and unidirectionally in stages and does not occur smoothly but rather in response to majordisorganization and disharmony. Newman drew from Prigogine’s (1980) Theory of Dissipative Structures and Young’s (1976) conceptualization of the evolution of human beings to describe the levels of consciousness in her theory and the dynamics of movement from one level to another. Figure 20-1 depicts the parallel between Newman’s theory of expanding consciousness and Young’s stages of human evolution. According to Newman, “We come into being from a state of potential consciousness, are bound in time, find our identity in space, and through movement we learn the ‘law’ of the way things work and make choices that ultimately take us beyond space and time to a state of absolute consciousness” (Newman, 1994a, p. 26). Within the theory, physical self-development binds one in time and space as one develops and establishes personal territory (stages two and three). Movement provides a way of controlling the personal environment and represents a choice point (stage four). When movement is restricted, as with illness or physical disability, “one becomes aware of personal limitations and the fact that the old rules don’t work anymore” (Newman, 1990a, p. 39), and one experiences the disconnectedness, disorder, and disequilibrium that are precursors to moving to a higher level of consciousness. Transcendence (stage five)—or expansion of boundaries of self and awareness of broader life possibilities—occurs in response as new order is established at a higher level (Newman, 1994a). New ways of relating are discovered, and the freedom that comes with transcending old limitations is discovered (Newman, 1990d). The highest levels of consciousness occur at the sixth stage, in which timelessness occurs, and in the seventh stage, which is absolute consciousness.

Pattern

Pattern has dimensions of movement and space-time. It is constantly moving unidirectionally and evolving and may be enfolded in a larger pattern that is in the process of unfolding. Using Rogers’ (1970) conceptualization of pattern, Newman (1986) states, “Pattern is information that depicts the whole, understanding of themeaning and relationships at once. It is a fundamental attribute of all there is and gives unity in diversity” (p. 13). Pattern is also a characteristic of wholeness and reveals the meaning of life (Newman, 1999). According to Newman (1987b), “Whatever manifests itself in a person’s life is the explication of the underlying implicate pattern…the phenomenon we call health is the manifestation of that evolving pattern” (p. 37). This phenomenon also includes concepts of health and disease.

Time, as a dimension of pattern, is conceptualized as either subjective or objective and also is viewed in a holographic sense. According to Newman (1994a), “Each moment has an explicate order and also enfolds all others, meaning that each moment of our lives contains all others of all time” (p. 62). Further, time is considered an index of consciousness (Newman, 1983) because as consciousness expands, space-time transcends limitations of linear and physical boundaries to extend beyond what is the here-and-now. However, what is truly important is that one be fully present in the moment knowing that all experiences are manifestations of the process of evolution to higher consciousness (Newman, 1994a).

Time and timing are further described as a function of movement (Newman, 1983) and part of the rhythm of living (Newman, 1994a). Time has importance in revealing patterns because extending the time frame helps nurses and patients recognize patterns and reorganizing activities (Newman, 1994a). Temporal pattern synchronicity between human beings and health care workers is also important to receptivity and health because these patterns are highly individualistic and influence how people respond to each other. Nurses who attempt to practice within this theoretical framework must be sensitive to synchronize their rhythms with those of clients with whom they are working. Newman refers to this as “the rhythm of relating” (1999, p. 227) and states that it is an indicator of the pattern of interacting consciousness. By attuning themselves to the rhythms of others, nurses assist individuals to identify patterns and move to higher levels of consciousness.

The dimensions of space and time are complementary and inextricably linked to each other as space-time or time-space, with time being increased as one’s life space decreases (Newman, 1979, 1983). Space has further been identified as life-space, personal space, and inner space (Newman, 1979), with personal space or territory very much involved in a person’s struggles for self-determination and status (Newman, 1990a). As consciousness expands, the distinction between the self and the world becomes blurred as one recognizes that essence extends “beyond the physical boundaries and is in effect boundarylessness, as one moves to higher levels of consciousness” (Newman, 1994a, p. 47).

According to Newman (1994a), movement is a reflection of consciousness, indicates inner organization or disorganization of people, and communicates the harmony of a person’s pattern with the environment. It is integral to relationships and “is a means whereby time and space become a reality” (Newman, 1983, p. 165). Rate of movement is seen as a reflection of pattern (Newman, 1995b). Space, time, and movement are linked. In fact, “the intersection of movement-space-time represents the person as a center of consciousness and varies from person to person, place to place, and time to time” (Newman, 1986, p. 49). When natural movement is altered, space and time are also altered. When movement is restricted (physically or socially), it is necessary for one to move beyond oneself,thereby making movement an important choice point in the process of evolving human consciousness (Newman, 1994a).

The evolution of consciousness is identified by patterns of increased quality and diversity of interaction with the environment (Newman, 1994a). Wholeness is identified in patterns of dynamic relatedness with one’s environment (Newman, 1999). Expanding consciousness is seen in the evolving pattern, and episodes of pattern recognition are turning points in the process of an individual evolving to higher levels of consciousness. Newman states that an individual’s current pattern is a composite of “information enfolded from the past and information which will enfold in the future” (Newman, 1990a, p. 39). Viewing this pattern in relation to previous patterns represents an opportunity for new action and expansion of consciousness.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice

From Newman’s perspective, nursing is the study of “caring in the human health experience” (Newman, Sime, & Corcoran-Perry, 1991, p. 3). The responsibility of the professional nurse is to establish a primary relationship with the client for the purpose of identifying meaningful patterns and facilitating the client’s action potential and decision-making ability. Newman emphasizes that the essence of the process is to be fully present in the transformation of clients and ourselves as we search for meanings in the lives of those who come to us at critical junctures of their lives (Newman, 2008). The nurse’s presence assists clients to recognize their own patterns of interacting with the environment. Insight into these patterns provides clients with illumination of action possibilities, which then opens the way for transformation to occur (Newman, 1990a). There is authentic involvement of the nurse with the client and mutuality of the interaction in discovering the uniqueness and wholeness of the unfolding pattern in each client situation and movement of the life process toward expanding consciousness (Newman, 2008).

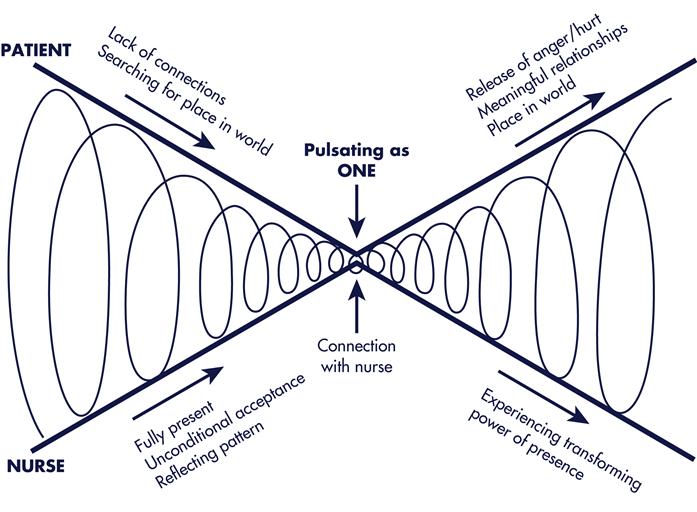

The nurse-client relationship is characterized by “a rhythmic coming together and moving apart as clients encounter disruption of their organized, predictable state and moving through disorganization and unpredictability to a higher, organized state” (Newman, 1999, p. 228). The nurse unites with clients at these critical choice points in their lives and participates with them in the process of expanding consciousness. The relationship is one of rhythmicity and timing. The nurse surrenders the need to direct the relationship or to “fix” things. As the nurse relinquishes the need to manipulate or control, there is a greater ability to enter into this fluctuating, rhythmic partnership with the client (Newman, 1999). Sensing into the whole requires a sensing into oneself, and a sense of stillness or centering is helpful to the process. Newman (1995b) elaborates, “The way to get in touch with the pattern of the other person is to sense into one’s own pattern” (p. 88). The nurse resonates with the client and is fully present and in “sync” with the client to facilitate formation of shared consciousness in what has been described as a dance of empathic relating (Newman, 1999). As the nurse dialogues and shares impressions and feelings with the client, pattern recognition occurs. Nurses make holistic observations of “person-environment behaviors that together depict a very specificpattern of the whole for each person” using terminology from individuals’ own stories and patterns (Newman, 1995a, p. 261). Descriptions of the total pattern of the person are then presented as sequential patterns over time (Newman, 1990b). The emphasis of the process is “on knowing/caring through pattern recognition” (Newman, 2008, p. 10). Figure 20-2 is Newman’s (2008) diagram of the nurse and patient coming together and moving apart in the process that includes recognition, insight, and transformation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree