Chapter 17 Neurological observations and coma scales

INTRODUCTION

Neurological observations enable the nurse to assess the neurological status of infants and children. A coma scale is a tool that instructs the assessor to perform and record a series of prescribed neurological and haemodynamic observations on a scaled chart. Results are plotted on each level of the scale and a corresponding number allotted. The numbers for the different observations are totalled to give an overall figure known as the coma scale rating, with a maximum score of 15 and a minimum score of 3. The lower the rating, the poorer the child’s neurological status (James & Trauner 1985).

RATIONALE

Deterioration in the level of consciousness can occur rapidly with devastating, sometimes fatal consequences which may only be averted with prompt action and treatment. Subtle changes in the neurological assessment may first be noted by a bedside nurse (Disabato & Burkett 2007). Therefore the ability to accurately assess the child’s neurological status and interpret the results in order to detect promptly any alteration in conscious level is a vital skill for a children’s nurse.

FACTORS TO NOTE

Rapid assessment

Initial management of an infant or child with a decreased conscious level is to support airway (immobilise cervical spine if trauma is suspected), breathing and circulation. A score (AVPU) has been introduced for rapid assessment of disability, particularly pre-hospital and in emergency departments. The score assesses neurological status as alert (A), responds to voice (V), responds to pain (P), or unresponsive (U) (ALSG, 2001). This scoring system, entitled the AVPU score, is simple to use and requires little training (Mackay et al 2000), allowing the observer to swiftly evaluate priorities of care without the need for additional charts or equipment. It does not, however, replace more accurate coma scales that are essential for serial assessment and evaluation of the patient’s level of consciousness.

Coma scales

Coma scales were introduced in the early 1970s in a successful attempt to standardise nursing and medical approaches to neurological assessment (Teasdale & Jennett 1974). Coma scales cover the following five main assessment criteria:

The most commonly used coma scale is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Devised by Teasdale and Jennett (1974), this is an adult scale that has also been adapted for children in recognition of the fact that verbal and motor responses must be related to the child’s age (Campbell & Glasper 1995).

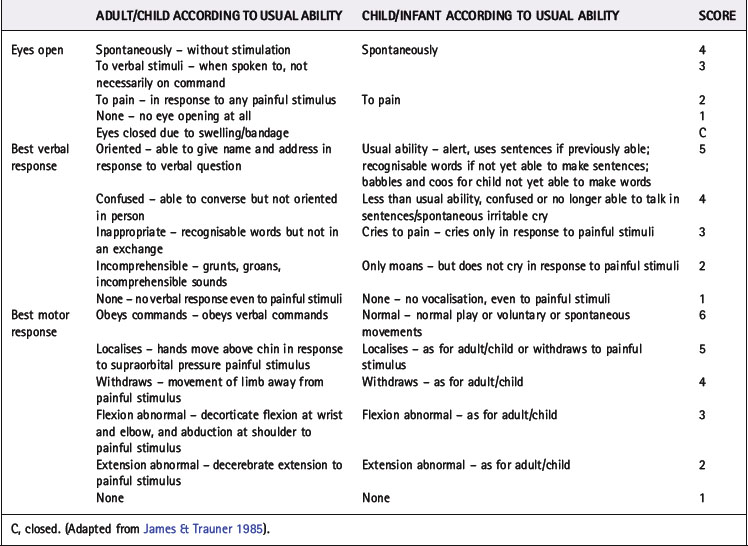

There are various paediatric adaptations of the GCS, for example that of James and Trauner (1985), and its subsequent revision as the Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH) model, as demonstrated in Table 17.1.

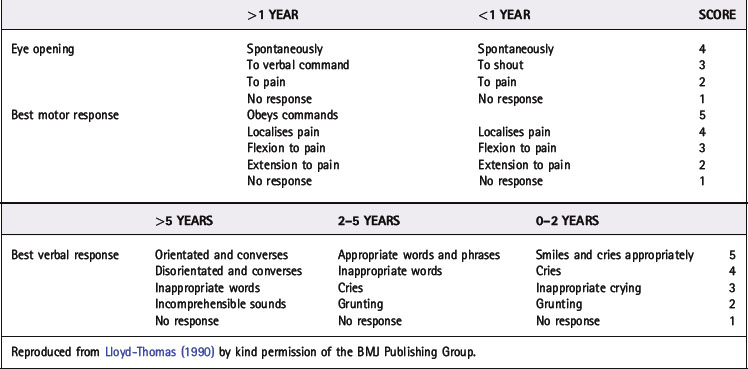

Another adapted GCS scale is known as the Paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (PGCS) or Adelaide scale. Physicians at Adelaide Children’s Hospital first adapted it for use in paediatrics and their adaptations were to the verbal and motor responses. These were developed to correlate with expected developmental milestones of children of different ages. The adaptations themselves were minor. They expected nurses to be trained to use the tool and to be able to apply knowledge of normal development when assessing the verbal and motor components of the scale. Table 17.2 demonstrates how a nurse would be expected to interpret a score against normal, verbal developmental milestones.

The Advanced Life Support Group (ALSG, 1997) developed a simplified version of a children’s coma scale for use in children under 4 years (Table 17.3).

Table 17.3 Advanced Life Support Group children’s coma scale: <4 years

| Response | Score |

|---|---|

| Eyes | |

| Open spontaneously | 4 |

| React to speech | 3 |

| React to pain | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| Best motor response | |

| Spontaneous or obeys verbal command | 6 |

| Reaction to painful stimulus | |

| Localises pain | 5 |

| Withdraws in response to pain | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion to pain (decorticate posture) | 3 |

| Abnormal extension to pain (decerebrate posture) | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| Best verbal response | |

| Smiles, orientates to sounds, follows objects, interacts | 5 |

| Crying | Interacts | |

|---|---|---|

| Consolable | Inappropriate | 4 |

| Inconsistently consolable | Moaning | 3 |

| Inconsolable | Irritable | 2 |

| No response | No response | 1 |

Reproduced from Lawton (1995) by kind permission.

Which scale to use is a matter of local choice according to the wishes of the multi-professional team. However, the nurse using the tool must have been given suitable tuition in how to use the tool and interpret the results, and be aware of the limitations of each scale. In addition, it must be remembered that the normal responses of a child who is developmentally delayed, or has an existing neurological deficit, may not fall within the specified age range, i.e. ‘child over 5 years’ and ‘child under 5 years’. It has been suggested that age-related scales should be replaced with criteria that reflect patients’ ‘usual ability’ to allow for infants/ children who have not achieved recognised developmental milestones (Warren 2000).

Early warning systems

Many acute children’s services are adopting Paediatric Early Warning Systems (PEWS) to assist in detecting children at risk of deterioration (Monaghan 2005). Most of these systems use age appropriate vital sign indicators to trigger intervention. PEWS scores have proved to identify patients at risk before a life threatening event occurs (Duncan et al 2006).

Applying a painful stimulus during neurological assessment

Frawley (1990) described the potential of damage to the nailbed following repetitive pressure assessments, thus advocating the use of side finger pressure. Following this article, many healthcare professionals adopted side finger pressure to avoid potential trauma, assuming peripheral pressure is advocated. However, many different modes of stimulus are regularly used in the paediatric setting, including squeezing the ear lobe, rubbing the sternum, pinching flesh under the arm, squeezing the shoulder and supraorbital pressure, with the most common being either nailbed or side finger pressure. No method of painful stimulus is regarded as a gold standard in the assessment of infants and children and few of the above techniques have been validated in paediatric practice.

Side finger pressure is performed by placing the child’s finger (third and fourth fingers are most sensitive) between the nurse’s thumb and a pen or pencil and gradually increasing pressure until a response is obtained (Fig. 17.1).

NEONATES

Neonates are notoriously difficult to assess neurologically and certainly most existing coma scales, even those that are adapted for infants and children, are not sufficiently accurate when assessing a child under 6 months of age (Allan 1994). Tatman et al (1997) devised and tested a grimace score for infants and children unable to vocalise. It is an assessment of orofacial movement as opposed to a vocal response and has five elements (Table 17.4). Primarily aimed at intubated children in an intensive care unit, it has also proved effective for neonates and infants. Hazinski (1999) highlights the need to evaluate the baby’s alertness and response to the environment, and Reeves (1989) highlights the importance of referring to the child’s parents who are most cognisant of their child’s normal behaviour. Palpation of the fontanelles is also beneficial when assessing for signs of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) or volume status in an infant. The anterior fontanelle should feel firm and flat; however, it will bulge if pressure in the superior vena cava increases (a physiological sign of raised ICP or congenital heart failure). A sunken fontanelle is a sign of volume depletion and dehydration (Hazinski 1999). Measurement of head circumference and observing the shape of the skull can also be of significant value when assessing a neonate.

| Orofacial Response | Score |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous normal facial/oromotor activity, e.g. sucks tube, coughs | 5 |

| Less than usual spontaneous ability or only responds to touch | 4 |

| Vigorous grimace to pain | 3 |

| Mild grimace or some change in facial expression to pain | 2 |

| No response to pain | 1 |

After Tatman et al (1997).