Chapter 33. Neurologic Emergencies

Amy Brown and Diana King

The emergency nurse encounters a variety of neurologic emergencies related to illness or injury, including stroke, head trauma, spinal cord trauma, headache, and meningitis. Regardless of cause, a neurologic emergency is one that causes severe temporary or permanent disability or is an immediate threat to the patient’s life. This chapter focuses on assessment and treatment of neurologic conditions caused by disease or pathologic abnormality. Patient assessment, anatomy, and physiology are also reviewed. Neurologic emergencies secondary to injury (i.e., head trauma and spinal cord trauma) are covered in Chapter 21 and Chapter 22, respectively.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The nervous system coordinates, interprets, and controls interactions between the individual and the surrounding environment. The central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system regulate most body systems.

Central Nervous System

The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord. Functional units of the CNS are neurons, cells that relay signals between the body and the brain. More than 100 billion neurons relay signals that control the body’s various systems. 2 Signal relay between neurons is controlled by neurotransmitters located at the synapse, or junction, between two neurons. Examples of neurotransmitters include acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, histamine, insulin, glucagon, serotonin, and angiotensin II. Signal movement along the neuron itself is an electrical phenomenon enhanced by the presence of myelin.

Brain

The adult brain weighs approximately 3 pounds, or 2% of total body weight. Brain tissue is the most energy-consuming tissue in the body, receiving approximately 20% of the cardiac output and using approximately 20% of the body’s oxygen supply. Structurally the brain consists of external gray matter and internal white matter. The brain has three distinct parts: cerebrum, brainstem, and cerebellum. The cerebrum, divided into two hemispheres, represents almost 90% of the brain’s weight. Bands of connective tissue, called the corpus callosum, relay information between the two hemispheres. Each hemisphere consists of lobes named for the adjacent portion of the skull (i.e., frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital). The brainstem, consisting of the midbrain, pons, and medulla, is continuous with the spinal cord and serves as an important relay and reflex center for the CNS. Nuclei for the cranial nerves are found in the brainstem. The brainstem also controls respiration, the cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal functions, equilibrium, and eye movement. 2 The cerebellum controls activities below the level of consciousness (e.g., posture, equilibrium). Within the brain, there is a series of interconnected cavities called ventricles. Most cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced within the ventricles by the choroid plexus and the ependymal cells.

In addition to the cranium, three layers of connective tissue, called meninges, surround and protect the brain. The dura matter, the outermost layer, is a double-layered fibrous membrane that lines the skull. One layer of the dura forms a tent over the brain and separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum. (This is the basis for the term supratentorial.) Below the thin middle subarachnoid mater is the subarachnoid space, which contains sinuses that collect venous blood from the brain and return blood to the internal jugular veins. CSF also flows in the subarachnoid space. The pia mater, the innermost layer, covers the brain and spinal cord and extends below the conus medullaris of the spinal cord to form the filum terminale.

Cranial Nerves

Twelve pairs of cranial nerves arise directly from the brainstem. Each nerve is identified with a Roman numeral and name. Cranial nerves may be sensory, motor, or both. Cranial nerve functions are not consciously controlled; therefore assessment of cranial nerves provides an accurate picture of brainstem activity and neurologic function. Table 33-1 lists cranial nerves and their functions.

| Number | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| I | Olfactory | Smell |

| II | Optic | Vision |

| III | Oculomotor | Elevate upper lid, pupillary constriction, most extraocular movements |

| IV | Trochlear | Downward, inward movement of the eye |

| V | Trigeminal | Chewing, clenching the jaw, lateral jaw movement, corneal reflexes, face sensation |

| VI | Abducens | Lateral eye deviation |

| VII | Facial | Facial motor, taste, lacrimation, and salivation |

| VIII | Acoustic | Equilibrium, hearing |

| IX | Glossopharyngeal | Swallowing, gag reflex, taste on posterior tongue |

| X | Vagus | Swallowing, gag reflex, abdominal viscera, phonation |

| XI | Spinal accessory | Head and shoulder movement |

| XII | Hypoglossal | Tongue movement |

Cerebral Blood Flow

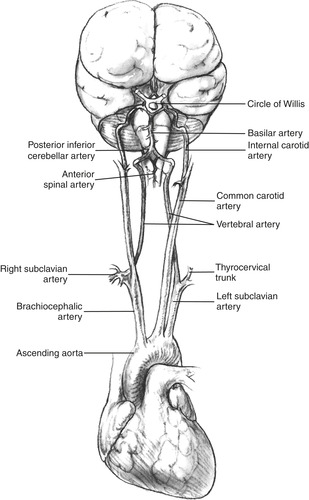

Two pairs of arteries connect to form the circle of Willis, the brain’s major blood supply. The terminal branches of each internal carotid artery branch into the posterior communicating artery and the middle and anterior cerebral arteries. This is commonly called the anterior circulation. The internal carotid arteries supply most of the cerebral hemispheres, basal ganglia, and the upper two thirds of the diencephalon (a division of the cerebrum). Two vertebral arteries unite to form a single basilar artery, which then divides into two posterior cerebral arteries. This artery complex supplies the cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, the occipital lobes, portions of the temporal lobes, and the posterior diencephalon. The anterior circulation supplies 80% of the blood to the brain, and the posterior circulation carries 20%. Figure 33-1 illustrates arterial blood supply to the brain. Venous blood drains from the brain through sinuses in the dura mater into the internal jugular veins.

|

| FIGURE 33-1 Origin and course of arterial supply to the brain. (From Davis JH, Drucker WR, Foster RS et al: Clinical surgery, vol 1, St. Louis, 1987, Mosby.) |

The brain occupies 80% of the cranium. Vascular volume and CSF account for the remaining 20%. Cranial rigidity limits the brain’s ability to tolerate volume expansion. If one component increases, the other components must decrease to prevent pressure on the brain. Cerebral blood flow is altered by changes in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). CPP is the difference between mean arterial pressure (MAP) and intracranial pressure (ICP) (MAP − ICP = CPP). The normal CPP is 60 mm Hg. Normal ICP is 10 to 15 mm Hg and is measured with invasive monitoring. Responses in fluid alterations can result in CSF reabsorption, shunting to the spinal subarachnoid space, or a decrease in cerebral blood volume into the sinus cavity. The body’s compensatory mechanisms allow for minimal changes in cranial volumes with minimal increases in ICP. 1

Cerebrospinal Fluid

CSF is produced in the ventricles by the choroid plexus at a rate of 7 to 10 mL/hr. CSF protects the brain and spinal cord by forming a shock-absorbing cushion, providing nutrition via glucose transport, and removing metabolic waste products. CSF also compensates for changes in pressure and volume within the cranium. Table 33-2 summarizes normal CSF characteristics.

| WBC, White blood cell; RBC, red blood cell. | |

| Quality | Value/Description |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Clear, colorless, odorless |

| Cell count | WBC count 5/mm 3 |

| RBC count 0/mm 3 | |

| Pressure | 80-180 mm H 2O |

| Glucose | 60-80 mg/100 mL (two-thirds serum glucose value) |

| Protein | 15-45 mg/100 mL (lumbar) |

| pH | 7.35-7.40 |

| Sodium | 140-142 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 120-130 mEq/L |

| Volume | 125-150 mL |

Spinal Cord

The spinal cord lies in the spinal canal of the vertebral bodies and is covered by meningeal layers. The adult spinal cord is approximately 16 to 18 inches long and extends from the brainstem to the intervertebral disk between L-1 and L-2. Sensory and motor neurons in the spinal cord conduct impulses to and from the brain. Unlike the brain, the spinal cord has white matter on the exterior and gray matter on the interior. Reflex arcs into the spinal cord operate without voluntary or conscious control. Table 33-3 lists these reflexes.

| Reflex | Segmental Level |

|---|---|

| Biceps | C5-6 |

| Brachioradialis | C5-6 |

| Triceps | C7-8 |

| Knee | L2-4 |

| Ankle | S1-2 |

| Superficial abdominal | T8-10 |

| Superficial abdominal | T10-12 |

| Cremasteric | L1-2 |

| Plantar | L4-5, S1-2 |

Peripheral Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system consists of 31 spinal nerves and the autonomic nervous system. Spinal nerves innervate skeletal muscle and a segment of skin called a dermatome. In certain areas spinal nerves form a network called a plexus; for example, the brachial plexus innervates the upper extremity.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system controls the body’s visceral functions. There is no sensory component; functions are entirely motor. The cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and the brainstem regulate activity. Two major divisions, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, respond to stressors such as fear or blood loss to provide extra energy or conserve existing energy stores. The sympathetic nervous system provides the body energy, creating the fight-or-flight response. Receptors are scattered throughout the body, including the skin. Parasympathetic nervous system receptors distributed primarily in the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis conserve the body’s energy.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

The most reliable indicator of neurologic function is the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). LOC must be reassessed and compared with the baseline to monitor the patient’s neurologic status. Question the patient’s family and significant other about changes in behavior, mood, or physical ability. Evaluate for signs of increasing ICP such as headache, nausea, vomiting, or altered LOC. Assess cranial nerve function and pupil size, equality, reactivity, and accommodation. The pupil dilates when increased ICP causes pressure on cranial nerve III; however, this is a late indicator of increasing ICP. Serial assessment is essential to identifying subtle changes that may indicate impending herniation. A universal tool such as the Glasgow Coma Scale is recommended (Box 33-1). Evaluating motor strength requires comparison of the patient’s dominant hand with the evaluator’s dominant hand. Sensory evaluation should include differentiation of dull and sharp objects. Assessment should also include identification of existing deficits such as muscle weakness, pupil abnormality, and gait disturbances.

Box 33-1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

G lasgow C oma S cale

EYE OPENING

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To verbal command | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

BEST MOTOR RESPONSE

| Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 |

| Withdraws from pain | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion | 3 |

| Abnormal extension | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

BEST VERBAL RESPONSE

| Oriented | 5 |

| Confused | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| TOTAL | 3-15 |

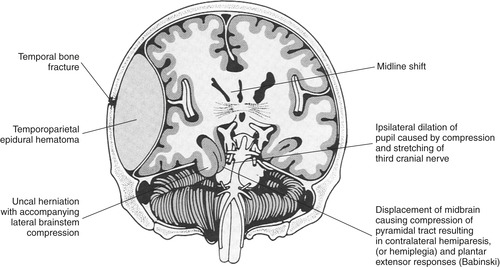

Stabilization of the patient with a neurologic emergency begins with the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Specific interventions depend on patient complaint and acuity. The patient with a severe migraine headache has different priorities than does a comatose patient. A patient with severe migraine requires pain management; the comatose patient needs support of the ABCs, management of increased ICP, and monitoring for impending herniation. Herniation occurs when increased ICP forces the brain downward through the foramen magnum. Compression of the brainstem impairs respiratory and cardiovascular function, ultimately causing death. Figure 33-2 illustrates this process. Controlling increased ICP includes use of medications such as osmotic diuretics, sedatives, and analgesics. Elevating the patient’s head facilitates venous drainage and decreases ICP; however, cervical spine injury must be ruled out before elevation. Decreasing stimulation such as noise and certain procedures such as suctioning can also affect ICP.

|

| FIGURE 33-2 Cross-section showing herniation of lower portion of temporal lobe (uncus) through tentorium caused by temporoparietal epidural hematoma. Herniation may occur also in the cerebellum. Note mass effect and midline shift. (From Meeker MH, Rothrock JC: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 10, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.) |

SPECIFIC NEUROLOGIC EMERGENCIES

Specific neurologic emergencies represent a threat to the patient’s life, integrity of specific functions such as vision, or quality of the patient’s life. Specific emergencies include headache, seizures, stroke, meningitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and myasthenia gravis. A brief review from the emergency nurse’s perspective is presented.

Headache

Headache is one of the most common complaints seen in the emergency department (ED), with only 1% to 2% not related to trauma. 6 It is important for the emergency nurse to remember that headache is a symptom of an underlying disorder rather than a diagnosis. The headache may be minor or represent a life-threatening situation such as subarachnoid hemorrhage; therefore careful assessment is essential.

Key points to identify during the patient assessment are time of onset, duration, intensity, and location of the headache. A brief history should include any injury, vision changes, seizure activity, recent infection, and/or diagnosis of hypertension. “The worst headache ever” should be viewed as a red flag for further evaluation.

Headaches may be caused by an extracranial or intracranial condition. Extracranial causes include acidosis, dehydration, hypoglycemia, uremia, and hepatic disorders. Ophthalmic causes of headache include glaucoma, refractory errors, inflammation, or allergic reactions (see Chapter 45). Poisoning and toxicologic emergencies can also cause headache (see Chapter 42 and Chapter 52). Other extracranial causes include ear infection, upper respiratory infection, sinus congestion, facial trauma, temporomandibular joint syndrome, toothache, anemia, polycythemia, electrolyte imbalance, and systemic infection. Women have reported headaches associated with the start of menses or during the premenstrual period. Identification and treatment of extracranial causes should relieve the headache.

Specific headaches related to intracranial conditions include migraine headache, tension headache, and temporal arteritis. Traumatic headaches may occur as an emergency or nonemergency. Nonemergency conditions include postconcussion or contusion headaches. Emergent conditions that cause severe headache include intracranial injury (see Chapter 21).

Migraine Headache

Twenty-three million Americans suffer migraine headaches. 7 Diagnosis of migraine headache is based on the patient’s history and presenting symptoms. Headache is rarely the only symptom. Before the diagnosis is made, other causes should be ruled out. Migraine symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and visual disturbances. Approximately 12% of the U.S. population has migraine headaches, and almost 70% of those with migraines have a positive family history. 7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access