Neuman Systems Model in Nursing Practice

Kathleen M. Flaherty

The philosophic base of the Neuman Systems Model encompasses wholism, a wellness orientation, client perception and motivation, and a dynamic systems perspective of energy and variable interaction with the environment to mitigate possible harm from internal and external stressors, while caregivers and clients form a partnership relationship to negotiate desired outcome goals for optimal health retention, restoration and maintenance.

History and Background

The Neuman Systems Model was first developed in 1970 to assist graduate students to consider patient needs in wholistic terms (Neuman, 1974, 2011).∗ “Helping each other live” is Neuman’s basic philosophy (Neuman, 2011, p. 333) and the Neuman Systems Model is a synthesis of systems thinking and wholism that provides a comprehensive systems approach for wellness-focused nursing care. Neuman’s model has been developed and influenced by personal experiences, open systems theories (Lazarus, 1981, 1999; von Bertalanffy, 1968), Selye’s (1950) construct of environmental stressors, holism (Cornu, 1957; de Chardin, 1955), gestalt theories of environment and person interaction (Edelson, 1970), and Caplan’s (1964) concept of prevention interventions, among others (Neuman, 2011).

Neuman developed the current conceptual model over almost four decades (Neuman, 1974, 1980, 1982a, 1989a, 1990, 1995a, 1996, 2002, 2011; Neuman & Young, 1972). Since 1980, a special nursing process format has been developed to facilitate model use in practice, the concept of environment has been expanded and clarified, a distinct spiritual variable has been added and explicated, the use of the term client has replaced patient, and clarifications of model componentsand relationships among these components have been provided (Neuman, 2011). The most recent publication of the Neuman Systems Model text uses the original diagram and presents the model components within the nursing metaparadigm of person, environment, health, and nursing (Neuman, 2011). This publication also provides guidelines for implementation of the model in clinical practice, nursing research, nursing education, and nursing administration, in addition to current and anticipated future applications (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011). Enhanced understanding of model components—client, reconstitution, and created environment—are provided (de Kuiper, 2011; Gehrling, 2011; Jajic, Andrews, & Jones, 2011; Tarko & Helewka, 2011).

In 1988, Neuman established the Neuman Systems Model Trustees Group to “preserve, protect, and perpetuate” the use of the model (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011, p. 355). The trustees established the Institute for Study of the Neuman Systems Model to provide support in the origination and testing of middle-range theories developed from the model (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011). Nurses continue to test and apply the Neuman Systems Model in nursing research, clinical practice, education, and administration. The utility of the model in each area is evidenced within Neuman’s books (Neuman, 1982b, 1989b, 1995b; Neuman & Fawcett, 2002, 2011). Fawcett compiled a bibliography of Neuman Systems Model applications. Scholars, practitioners, and students can access this bibliography, updated through July 2011 (an ongoing project), at the Neuman Systems Model website (http://neumansystemsmodel.org). Recent literature describes use of the Neuman Systems Model in research and praxis in a variety of applications. Some of these treatments include use of the model for evidence-based practice development (Breckenridge, 2011); Merks, Verbeck, de Kuiper, et al., 2012), promoting student coping and success (Das, Nayak, & Margaret, 2011; Pines, Rauschhuber, Norgan, et al., 2012; Yarcheski, Mahon, Yarcheski, et al., 2010), family participation in critical care (Black, Boore, & Parahoo, 2011), spirituality in adults (Cobb, 2012; Lowry, 2012), nurse stress in emergency care (Lavoie, Talbot, & Mathieu, 2011), and application in nursing administration (Shambaugh, Neuman & Fawcett, 2011).

Neuman considers “client” to be an individual, a group, a family, or a community system. Each client is viewed with five variables that interact synergistically in relation to each other and reciprocally with the internal, external, and created environments in which the client exists. The five client variables essential to the Neuman model are physiological, psychological, developmental, sociocultural, and spiritual. Intrapersonal, interpersonal, or extrapersonal environmental stressors can affect potential or actual reactions within the client system.

A continuum of increasing wellness to increasing illness, and even death, is the basis by which wellness is understood. Whenever the system has more energy stored than needed, the client is considered within the range of wellness. Conversely, whenever system energy depletion occurs, variances from wellness (illness) are exhibited in clients. In the Neuman model, optimal system stability is the greatest degree of client wellness. Consequently, the major goal of nursing is to assist the client in achieving system stability through the attainment, retention, and maintenance of optimum health. Accordingly, it is the nurse who creates the connections among the client, environment, health, and nursing that lead to systemstability. Nurses practicing according to the Neuman model promote system stability through primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention-as-interventions.

Client system stability is significantly affected by clients’ perceptions that in turn have a significant effect on the increase or decrease in energy available to them. Therefore, if the nurse is to facilitate energy use in wellness promotion, accurate appreciation of the client’s perception of the health care situation is essential (Neuman, 2011).

Neuman uses the term wholism to reference biological and philosophical concepts “implying relationships and processes arising from wholeness, dynamic freedom, and creativity in adjusting to stressors in the internal and external environments” (Neuman, 2011, p. 10). The Neuman Systems Model incorporates the structure and process components of open systems models (Sohier, 2002). Such incorporation of open systems models to her conceptual framework is demonstrated by Neuman’s technical use of the word wholism as opposed to holism. The “homologous” (Neuman, 2011, p. 9) nature of open systems, the model and nursing concepts empowers the nurse using the Neuman Systems Model to fulfill two concurrent responsibilities inherent to the model. First, Neuman’s emphasis on wholism motivates nurses to view the client as an interrelated whole different from and greater than the sum of the parts. Second, nurses using the Neuman model are able to focus on a particular subpart of a client situation without neglecting the interrelatedness of the system.

Overview of Neuman Systems Model

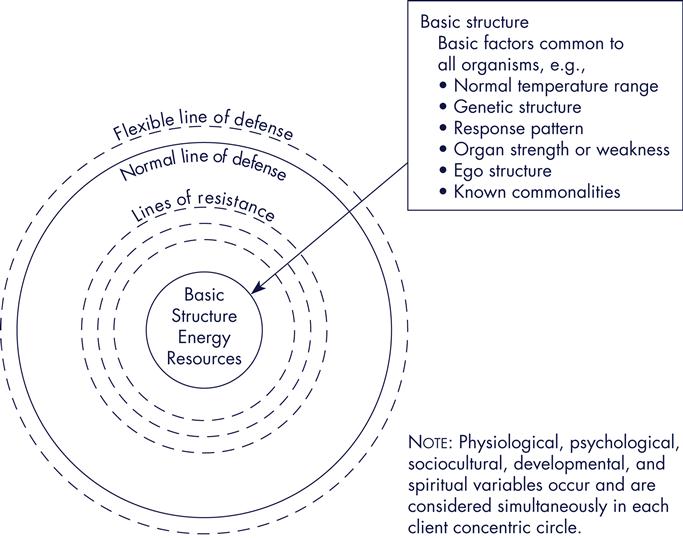

The aim of the Neuman model “is to set forth a structure that depicts the parts and subparts and their interrelationship for the whole of the client as a complete system” (Neuman, 2011, p. 12). As depicted in Figure 11-1, and beginning from the center of the figure, the Neuman model identifies a basic structure of energy resources, variables, system boundaries, and the environment as the core subparts of the system.

At the core of the diagram, energy resources are noted. A constant energy exchange occurs between the client system and environment. The client maintains and augments system stability by using energy, regarded as a positive force available to the system. As such, stability is not static but adaptive and developmental in nature because the client system is considered an open system in a state of constant change.

A series of protective rings encircle the center structure and protect the system from environmental stressors. Each system component is intersected by five variables (physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual). These five variables interact synergistically and wholistically within all parts of the client system (Neuman, 2011).

As noted, Neuman considers “client” to be an individual, a group, a family, or a community system. Accordingly, the substance of each of the five variables depends on which client system is being considered. For example, the physiological variable is defined as “body structure and internal function” (Neuman, 2011, p. 16). Therefore, circulation could be considered a physiological variable for anindividual. Objective data that reflect the physiological variable of circulation would include vital signs, peripheral pulses, and heart sounds. However, for a community system, the physiological variable could include vital statistics, morbidity, mortality, and general environmental health (Hassell, 1998, Jajic, et al., 2011). Psychological variables include “mental processes and interactive environmental effects…” (Neuman, 2011, p. 16). For example, self-esteem and its effect on relationships for the individual and communication patterns for a family could be considered components of the psychological variable. The developmental variable refers to life developmental processes and/or developmental tasks that relate to life changes (e.g., individual adjustment to aging parents or “empty nest syndrome” for a couple). The combination of social and cultural functions or influences defines the sociocultural variable. Both ethnic cultural practices and health belief practices are examples and important components of this variable regardless of how the client system is defined. Client belief influence is exhibited in the spiritual variable. As an example, spiritual factors could include a person’s worldview and perceived sources of strength or hope, or the predominant religious culture of a community system (Hassell, 1998). Neuman proposes each of these five variables as system subparts that are open, with energy exchange existing within and between the client system and the environment (Neuman, 2011). As noted in Figure 11-1, these five variables are considered simultaneous influences on the system.

At the center of the diagram is the client’s basic structure composed of energy resources that Neuman calls “survival factors” (Neuman, 2011, p. 16). Within the basic core, the five interacting variables (physiological, psychological, developmental, sociocultural, and spiritual) contain commonly known norms (Neuman, 2011). For example, the individual as client possesses common resources such as organ structure and function, mental status, and coping mechanisms that are integral to core system stability. Alternatively, the client as family has a basic structure that includes specific roles, attitudes, and cultural beliefs that provide energy resources and stability.

Lines of resistance protect the client’s basic structure. These are defenses activated by the client when internal or external environmental factors stress the client system. Broken lines that circle the basic structure diagrammatically represent these lines of resistance. The internal immune system is an example of a physiological variable activated within the lines of resistance when infection invades an individual. The client system restabilizes for wellness/energy conservation (reconstitution) whenever these lines of resistance effectively mobilize internal and external resources. Energy depletion and ultimately death occur whenever the lines of resistance are ineffective (Neuman, 2011). Ineffective lines of resistance can be seen when an individual has had extensive chemotherapy (an external stressor), with the result of the immune system being severely compromised. This compromise of the immune system is an example of system energy depletion. Mobilization of external resources (transfusion) helps the client’s internal resources and strengthens the lines of resistance. The outcome of these added external resources is a more physiologically stable client.

Neuman regards the normal line of defense as the usual or standard client level of wellness that protects the basic structure as the client system reacts to stressors. A solid line that circles the lines of resistance and basic structure represents this protection. The standard level of wellness is achieved by the interaction of the five variables over time. Clients’ usual level of wellness (the normal line of defense) is maintained, increased, or decreased as stressed clients react to a stressor encounter (Neuman, 2011).

The normal line of defense is encircled by the flexible line of defense, represented by broken lines that suggest the constant interaction of the environment and the open nature of the system. The flexible line of defense expands and contracts depending on the protection available to the client at any point in time. For example, healthy lifestyles and effective coping mechanisms function as possible expanders of the flexible line of defense. Stressors may invade the client/client system but are buffered by this line, thereby freeing clients from reactions to those stressors. The protection of the client system is proportionate to the distance between the flexible line of defense and the normal line of defense (Neuman, 2011).

Neuman has clarified and expanded the concept of environment to include three discrete yet interactive environments that influence the system. Neuman’s most recent publication (2011) describes how the internal and external factors that interact with the client/client system are considered part of the environment. The intrapersonal environment is the internal environment that includes influences within the system. The external environment is considered both interpersonal andextrapersonal in nature. The created environment is the third distinct aspect of Neuman’s construct of environment. Neuman describes this created environment as unconsciously developed by the client system and as “a symbolic expression of system wholeness” as it mobilizes all system components towards wellness (Neuman, 1989, p. 32; 2011, p. 20).

The maintenance of purposeful system stability involves constant energy interchange with the internal, external, and created environments. The manner in which the individual client processes a life event such as pain is based on past experiences with pain. This is an example of the interaction of internal, external, and created environments. The client’s past experiences with pain and the elicited coping mechanisms and outcomes result in the creation of a perceptual reality for the interpretation of the current situation. This created perceptual reality (created environment) influences the client’s response to the painful situation (de Kuiper, 2011).

Client system stability can be affected by internal or external environmental factors, which Neuman defines as stressors. Neuman considers the effect of these stressors, whether they are positive or negative, to be dependent on the client’s perception of the stressor. When stressors penetrate the flexible and normal lines of defense and the lines of resistance are activated, energy depletion and system instability occur. However, system stability may be maintained when stressors are deflected or modulated by the interaction of the five system variables within the flexible and normal lines of defense and the lines of resistance (Neuman, 2011).

Stressors that can influence client system stability are classified in three ways: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal. First, internal stressors that occur within the client system boundary are classified as intrapersonal. Atherosclerosis and resultant hypertension are examples of an individual client’s intrapersonal stressors. Second, stressors that occur in the external environment outside but proximal to the client system boundaries are classified as interpersonal. The individual client’s role in the family, perceptions of caregiver, and friend relationships are examples of these forces. Third, extrapersonal stressors are those that occur distally to the client boundary. Community resources, financial status, and employment of the individual client are examples of extrapersonal stressors. Because of the complexity of human beings, all three stressors may be exhibited in clients and observed by nurses in any nursing situation (Neuman, 2011).

Application of the Neuman Systems Model in nursing praxis can occur in any setting. In each nursing situation, the nurse completes a wholistic assessment of actual or potential stressors, client variables, and boundary impact. The nurse determines the client’s perspective before the analysis and synthesis of the objective and subject data collection. In addition, client strengths, weaknesses, and resources are considered.

Identification and differentiation of both nurse and client perceptions in the health care situation are required by the Neuman Systems Model. This requirement is rooted in the understanding that client stability and optimal health outcomes can be compromised by incongruities between nurse and client perceptions. These incongruities can be avoided by developing a partnership between the nurse and the client, with care based on their complementary perceptual understandings. The result of such a complementary partnership is joint planning of care based on goalclarification. Because perception can influence client response and resistance to a stressor, resolving the potential perceptual differences for nurses and clients is essential within the Neuman model. Neuman has provided a formalized nursing process that includes specific subjective data gathering about the client perspective (Neuman, 2011). Once data collection is complete, the nurse analyzes and synthesizes the data and in conjunction with the client determines nursing diagnoses, goals, outcomes, and interventions.

There are three different intervention modalities or nursing actions specific to the actual or potential stressor response from the client system described by Neuman. These interventions are dynamic and cyclical in nature and are labeled as primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention-as-interventions. Nurses may use the three intervention modalities concurrently to achieve a synergistic effect. Optimal client wellness or system stability is the ultimate goal of these three interventions. Primary interventions retain, secondary interventions attain, and tertiary interventions maintain system energy (Neuman, 2011).

Before the client system reacts to stressors and to prevent a stressor invasion, nursing actions should be implemented as primary prevention interventions to strengthen the flexible line of defense. This preemptive nursing act promotes the retention of client system wellness (Neuman, 2011). Nursing actions such as instituting a wellness program that integrates healthy nutrition and exercise would be an example of primary prevention-as-intervention.

Nursing actions necessary for the client system to attain restabilization (reconstitution) through energy conservation and the use of internal and external resources are considered secondary preventions. These interventions protect the basic structure of the system. The nurse implements secondary prevention actions whenever stressor reactions occur and symptoms are present. Symptom treatment of hypertension is an example of secondary intervention. Dynamic system stability is achieved and the basic structure is protected whenever the lines of resistance are strengthened. “Reconstitution may be viewed as feedback from the input and output of secondary intervention” (Neuman, 2011, p. 29). If secondary preventions are not successful in reconstituting client system energy to counterbalance system reaction, death can occur (Neuman, 2011).

After a therapeutic modality and reconstitution, the maintenance of client system stability is achieved by tertiary prevention-as-interventions (Neuman, 2011). Nursing actions such as education and reinforcement about nutrition, exercise, and medications that can maintain the reconstitution of the client with hypertension are examples of tertiary prevention. Applications of the Neuman Nursing Process Format to specific client situations are provided later in this chapter.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Neuman’s Model

The Neuman Systems Model provides a structure for critical thinking in several ways. As a systems-based model, conceptualization of clinical nursing phenomena can be approached wholistically while appreciating the interaction of the part and subpart components of the system that adapt synergistically and developmentally to promote system persistence (Fawcett, 2005; Neuman, 2002). In addition, thissystems-based model allows for reconceptualization when clinical situations undergo rapid change. In such rapid change situations, the Neuman Systems Model allows for the identification of interrelationships between identified systems, parts, subparts, and the environment, leading to consequent and rational nursing actions. Therefore, this conceptualization of nursing phenomena promotes efficacious critical thinking processes such as application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. The Neuman Systems Model nursing process categories of nursing diagnoses, nursing goals, and nursing outcomes create a format for purposeful critical thinking and problem solving that translates to action (Freese, Neuman, & Fawcett, 2002; Freiburger, 2011).

Freese and colleagues (2002) identify guidelines for Neuman Systems Model–based clinical practice using Neuman’s Nursing Process Format. These guidelines include the process of praxis, diagnostic taxonomy, typology of clinical interventions, and typology of outcomes (p. 38). The Neuman Systems Model–based clinical practice guidelines are congruent with the current standards of nursing practice articulated by the American Nurses Association (2004) as the nursing process. Both depictions of the nursing process are construed as iterative and overlapping subprocesses of thought rather than a linear process. Table 11-1 presents the relationship between critical thinking and the Neuman Systems Model nursing process.

TABLE 11-1

Critical Thinking and the Neuman Systems Model Nursing Process

| Critical Thinking Focus | Neuman Systems Model Nursing Process | Nurse-Client Partnership Relationship |

| Conceptualization Analysis Observation Experience Reflection Communication | Nursing Diagnosis:Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|