Chapter 32. Narrative Research and Analysis

Sion Williams and John Keady

▪ Introduction

▪ What is narrative research?

▪ Locating narrative

▪ Narrative methods

▪ Narrative analysis

▪ Evaluating narrative

▪ The use of narrative in nursing research: a case example

▪ Conclusion

Introduction

Narrative equals life; absence of narrative equals death. (Tzvetan Todorov cited in Christman 2004, p. 695)

As human beings we portray ourselves through story, and story-making is integral to human consciousness (Bruner 2004). At its most basic level, narrative research and analysis is about asking for people’s stories, listening and making sense of them and establishing how individual stories are part of a wider ‘storied’ narrative of people’s lives (Bruner 2004 and Roberts 2002). Riessman (1993) highlighted the lack of a precise definition resulting in researchers adopting a variety of stances that use narrative as a metaphor for ‘telling about lives’ that often includes ‘just about anything’ (p. 17) or is particularly restrictive. The defining attributes of narratives as research focus on their quality as ‘discrete units’ that incorporate a beginning and ending (Riessman 1993), and at the heart of the narrative enterprise is the study of lives through the use of biographical research approaches (Roberts 2002). However, the conceptual diversity of narrative approaches, and the lack of a ‘binding theory’ (Riessman 1993), results in a range of strategies proposed to interpret and represent people’s lives based upon their individual accounts.

What is narrative research?

Narrative research has emerged from a range of disciplines, such as anthropology, linguistics, cultural studies and ethnography (Berger 1997 and Polkinghorne 1988). The mode of analysis has also evolved and reflects the influence of these different disciplines on the form and function of narrative research, resulting in highly structured analysis or interpretive strategies (Wiles et al 2005). Osatuke et al (2004) asserted that narratives preserve the ‘rich complexities of lived experience’ and draws listeners to the person’s ‘complexly textured world’ through characterisation, plot and theme (p. 193). There are a number of proposed evaluative criteria for narrative research, such as trustworthiness and authenticity (Mishler 1995) and a process of ‘consensual validation’ (Lieblich et al 1998).

Narrative research appears as both a separate and an integrated approach. The lack of a ‘binding theory’ (Riessman 1993) results in the narrative research form emerging, and being located within, an existing philosophical and methodological stream, primarily within the fields of phenomenology and ethnography which are also characterised by diversity. For instance, there are numerous examples of narrative work as part of the emphasis upon meaning elicited through text and discourse based on the phenomenological hermeneutic approach underpinned by the philosophy of Paul Riceour (Cole & Knowles 2001).

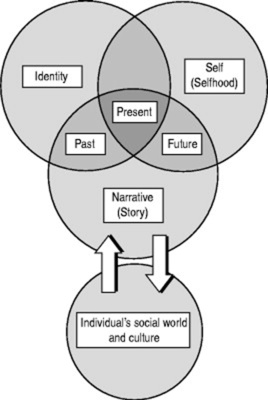

A core value of narrative research is that it provides a ‘lens’ through which to explore the complexities and map out the relationships between selfhood, identity and the social world (Bruner 2004, Lieblich 1998, Roberts 2002, Somers 1994 and Somers 1994). Such an account examines the interplay between past and present construction of self, and at its heart is concerned with uncovering an emic perspective on the life-course through the ‘performance’ of a narrative (Fig. 32.1).

|

| Figure 32.1 The narrative lens. |

Mishler (1995) provided a three-part typology for classifying narrative studies according to the focal point of the research. Firstly, reference and temporal order identifies relationships between narrated events and ‘real-time’ events; secondly, textual coherence and structure refers to the linguistic and narrative strategies for the ‘construction of the story’ (p. 7); and thirdly, narrative sets the story in a wider social and cultural context. The typology developed by Mishler (1995) summarises the key features of narrative research as ‘process’ and establishes the importance of ‘form’ and ‘function’ in narrative research.

To develop an understanding over how these core relationships work in practice, Lieblich et al (1998) provided an important heuristic framework that separates the interpretation and analysis of narrative according to what is described as an holistic-to-categorical continuum, clarifying the significance of ‘form’ and ‘function’ in narrative research approaches (Box 32.1).

Box 32.1

▪ Holistic-content mode embraces the life story as a whole and addresses the meaning from the text in its entirety.

▪ Holistic-form mode utilises the guide of looking for plots or structure to life stories, seeking meaning as turning points and endings.

▪ Categorical-content mode is similar to content analysis and involves the separation of textual utterances in order to construct an analysis.

▪ Categorical-form mode is more linguistic in orientation, the use of metaphors and language to articulate underpinning ideas and thoughts.

Source:Lieblich et al (1998).

The philosophical and methodological roots of narrative research are rich and varied (Manning 1994 and Roberts 2002) and formulate an intriguing and flexible method of qualitative inquiry. Narrative research is not alone in being the subject of multiple variations and interpretations (Denzin 1994 and Denzin 2000) and the developments in narrative research are driven by a renewed interest in ‘narrative’ and ‘story’ across a range of disciplines. Moreover, interest is fuelled by a cross-fertilisation of ideas, methods and techniques of data collection and analysis.

Initially grounded in life history research (Lawler 2003 and Roberts 2002), narrative research has emerged centre-stage in sociology, particularly in the case of ethnography, as there has been a marked shift away from modernist arguments about the dominance of social structures (Lawler 2003). The scope of narratives as a form has been extended beyond representation (Riessman 1993) and they are now identified as having not only a personal but a public dimension; they ‘neither begin nor end with the research setting: they are part of the fabric of the social world’ (Lawler 2003, p. 243).

The adoption of particular interpretive strategies reflects social, historical or cultural orientations and involves a dynamic movement in the treatment of narratives. For example, there is an increasing interest in ‘textuality’ as part of narrative in the social sciences, with a renewed emphasis on written or spoken text as not only reflecting but producing social reality (Lawler 2003). Health care and nursing retains some diffuse conceptions of ‘narrative’ and its relationship to ‘story’ (Paley & Eva 2005) yet also mirrors a shift in the attentiveness to the personal construct of reality and its role in understanding the wider social ‘story’ of care (McCance et al 2001).

Locating narrative

A narrative account requires two key features to be present: a discourse as the basis for a narration, and the narrative which has to be attentive to time and therefore involves a temporal dimension (Lieblich 1998 and Roberts 2002). A third feature delineates the architecture of the narrative form, described by Denzin (1989) as a simple scheme consisting of a beginning, a middle and an end that is linear and sequential, has a ‘plot’ but is also past orientated and ‘makes sense’ to the narrator.

We would suggest that narrative research and narrative accounts are best understood using a dramaturgical rather than the traditional literary metaphor. Indeed, Goffman (1974) identified storytelling as a ‘performance’, and Riessman (1993) emphasised the importance of ‘performance’ in representing experience as narrative. This metaphor highlights the centrality of communication and the purpose of conveying meaning, or what Gubrium and Holstein (1997) describe as ‘horizons of meaning’ to an audience.

Identity is central to the narrative inquiry (Bruner 2004 and Roberts 2002) and the weaving of the past and present elements of identity into a temporal dimension develops a construction of ‘self’ that can be understood separately – as occurring in the past – and also synthesised into the present in a temporally organised whole (McAdams & Janis 2004). In this sense narratives are constructed and ‘authored’ by individuals with a purpose and presented as ‘unified’ (McAdams & Janis 2004). This is developed further by Somers (1994) who highlighted the relational aspects of narratives by mapping out what can be understood as four interrelated narrative ‘scripts’ that are an inherent part of any performance. These are:

▪ the person’s own ‘inner world’ (ontological narrativity);

▪ the social context and its expectations (public narrativity);

▪ the broad cultural and historical context (master narrativity);

▪ the researcher’s frame of reference (conceptual narrativity).

A key reciprocal relationship exists between ontological and public narrative, informing the formulation of selfhood. For instance, McCreight (2004) identified the ‘grief ignored’ by male partners following a miscarriage and stillbirth. Previous research and a social (public) narrative focused on the expectation that men were emotionally strong to support their partner. However, McCreight (2004) highlighted how such a perception contrasted with the inner world experience of men and what Somers (1994) characterised as their personal (ontological) narrative. The public narrative of men only having a supportive role ignored the meanings they attached to the loss and their personal emotional tragedy, involving self-blame, loss of identity and the need to hide their feelings of grief and anger.

Not only do narrators provide a structure (Denzin 1989), but researchers impose and seek ‘plots’ and there is a recognised tendency of narrative work to arrange events and the structure of a life in a coherent order (Plummer 2001). Riessman (1993) identified a number of key elements that provide form in narratives:

1 Structure – the common elements include a starting point or point of departure for researchers, as it unifies form and function: an abstract (summary of the substance of the narrative), orientation (time, place, situation, participants), complicating action (sequence of events), evaluation (significance and meaning of the action, attitude of the narrator), resolution (what finally happened) and coda (returned to the present).

2 Plot – plots frame the narrator’s sense of meaning and these vary from tragedy, comedy, romance, satire and so act as archetypes and points of reference for representation.

3 Agency and truth – the degree of ‘truth’ attached to narrative reflects the researcher’s perspective (in essence their conceptual narrative), whether linguistic or phenomenological.

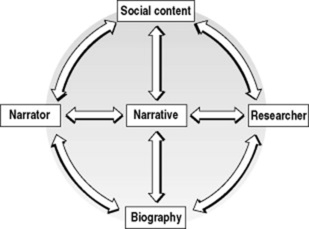

The narrative involves the narrator’s performance to the researcher-as-audience and incorporates how the ‘performance’ is viewed and interpreted. Somers (1994) challenged this paradigm and described it as being ‘representational’ – in other words, providing ‘false order’ to the chaos of lived experience. Hence, Somers (1994) presented different layers of narrative that involve the participant and researcher and focus on personal and social dimensions of identity, emphasising the dynamic nature of social interchange (Gergen & Gergen 1984). Furthermore, recognising the importance of conceptual narratives highlights the importance of how researchers approach narratives based on a particular frame of reference. For instance, as Riessman (1993) identified over a decade ago, narrative research drawing on Western traditions tends to emphasise the importance of chronological, rather than episodic sequences in narrative, and the spectrum of approaches are influenced by a range of social science perspectives. Representation of the ‘story’ in narratives is informed not only by conceptual narrativity but also by the cultural master narrative and public narrative, that provide the ‘theatre’ of social context for the narrator’s performance and underpin the judgements made by the researcher-as-audience, as well as its grounding in their respective biographies (Fig. 32.2).

|

| Figure 32.2 The dynamics of narrative research: A narrative quadrangle. |

Narrative methods

McCance et al (2001) highlighted that interviews are the most frequently chosen method when using narratives approaches. The shape and form of the encounter will be determined by the approach adopted to frame the particular narrative study and will require attentiveness to the complexities of ‘talk’: its multilayered, contextual and aural qualities (Wiles et al 2005). A number of issues need to be borne in mind in considering the narrative interview, such as:

2 Asking the right question – the content of the interview questions is also important and Riessman (1993) suggested the use of an interview guide consisting of five to seven broad questions based upon the research question.

The basic form of a narrative interview may also be developed as part of a group and participatory process (Arlanda & Street 2001) and requires equal sensitivity. The central aim of any interview is to facilitate the story to be told and see how respondents make sense of their lives (Riessman 1993) and describe their experience and actions (Polkinghorne 1995).

Narrative analysis

Paley and Eva (2005) noted that although ‘story’ and ‘narrative’ are used interchangeably as terms, not all ‘story’ is narrative but narrative includes story. This was a theme reiterated by Roberts (2002) and important in locating the place of narrative research in the broader area of biographical approaches. Making sense of narratives frequently refers to the terms ‘analysis’ and ‘interpretation’ being used interchangeably (Wiles et al 2005). Some clarity is provided by conceptualising analysis as an activity of making sense of data whilst interpretation is more than analytic explanation. Rather, interpretation involves understanding the meaning of social action and gets ‘under the skin’ of the complexity described by Somers (1994) as a person’s ‘ontological narrative’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree