Chapter 36 MOVEMENT AND EXERCISE

The human body is ideally suited to movement, and regular exercise promotes health, feelings of wellbeing and prevents illness throughout the lifespan. Exercise is made possible by the musculoskeletal, nervous and cardiovascular systems that work together to make movement possible. Information on the function of the cardiovascular and nervous systems is provided in Chapters 38 and 41.

Sustained regular exercise stimulates the body and mind and there are numerous benefits such as maintenance of cardiopulmonary efficiency, increased muscle tone and strength, joint mobility, sound sleep as well as a decrease in boredom and stress. Regular exercise can affect blood cholesterol levels by increasing high-density lipoproteins (the ‘good’ cholesterol). Goldberg and Elliot (2000) suggest that the risk of developing diabetes decreases in those who are active, regardless of body weight, which is thought to be a factor in the development of this disease. Current information suggests that obesity and being overweight can cause serious health problems, but moderate regular exercise can control weight.

THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

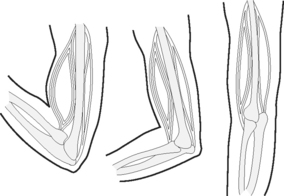

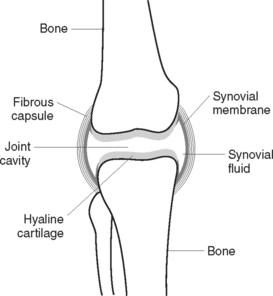

The musculoskeletal system is composed of many structures that work together to produce movement and provide support and protection for organs. About 600 voluntary or skeletal muscles form the flesh of the body. Skeletal muscle is attached to bone and classified by the kind of movement it makes; for example, flexors allow joints to bend or flex, while abductors allow shortening so that joints are straightened or abducted (moved away from the body). Muscle tissue is capable of contraction and relaxation, after stimulation by a motor nerve. Muscle develops under several influences such as exercise, nutrition, gender and genetic predisposition, which accounts for variations in muscle size and strength between individuals. When muscle contracts it pulls on a bone or bones and produces movement at a joint, where two bones meet. As joints are weak points in the skeleton, synovial fluid, cartilage, ligaments and tendons add protection. See Clinical Interest Box 36.1 for facts on muscle coordination.

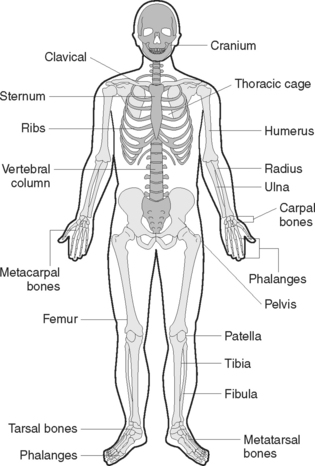

The skeleton (Figure 36.1) gives the body shape, protection, stores minerals, forms blood cells (haematopoiesis) and allows movement. Normally there are over 200 separate bones and supportive ligaments, as well as fibrous bands of tissue called tendons, which connect muscle to bone. The human skeleton is separated into the axial and appendicular skeleton. Axial skeleton bones form the head and trunk, all others belong to the appendicular skeleton, or bones of the extremities.

Figure 36.1 The skeleton, anterior viewThe axial skeleton appears a darker grey than the appendicular skeleton

Bone is composed of different tissue and classified by location and shape, such as long, short, flat, irregular or sesamoid, such as the patella, or kneecap. Long bones in the arm and leg differ from short bones in the wrist and ankle, and flat bones that form the shoulder blade are different again from irregular shaped bones such as the jaw and vertebrae. Bone begins as cartilage that eventually hardens to form bone. Bone remodelling (the creation and destruction of bone) is a lifelong process and performed by bone-forming cells called osteoblasts, and bone-absorbing cells called osteoclasts. Normal bone growth depends on a healthy diet, as well as other hormonal factors (e.g. oestrogen affects bone formation) and physical factors. Despite the rigidity of the skeleton, humans are capable of moving and bending in almost any direction and this flexibility is largely due to the skeleton’s many movable joints (Figure 36.2).

BODY POSTURE AND MECHANICS

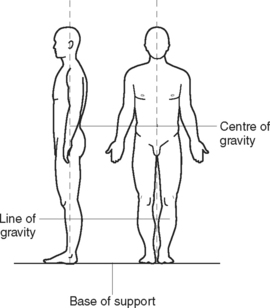

Fatigue, muscle strain and injury can result from improper use or positioning of the body during activity or rest. Good posture is achieved when all parts of the body are in correct body alignment, and is important when sitting, lying, standing or moving. Normal spinal curves should be maintained and the joints should be supported in their normal positions. Good posture (Figure 36.3) and alignment reduces strain on all muscles and joints (Figure 36.4) and enables internal organs to function without interference; for example, full lung expansion is facilitated. Body mechanics is the term used to describe the physical coordination of all parts of the body to promote correct posture and balanced effective movement. The practice of correct body mechanics results in less fatigue and reduces the risk of muscle and joint injury.

ATTITUDES, VALUES AND FEARS TOWARDS EXERCISE

Children learn the value of regular exercise if they are brought up in an environment in which exercise is seen in a positive way and both parents and children discover ways to incorporate exercise into their daily routine. Later on, these children are more likely to continue to exercise into their old age. On the other hand, sedentary parents may send the message to their children that exercise is too much trouble and not worth the effort. Thus early familial attitudes towards exercise can form lifetime patterns of behaviour. Personal values about one’s appearance (e.g. it is better to be slim or build up muscle to produce a ‘good’ body) can motivate both young and older adults to exercise regularly. Nurses need to dispel fears and anxiety about exercise and activity that many people may have because of chronic conditions or lack of information about the benefits of exercise, and respond appropriately to clients’ questions. (See Clinical Interest Boxes 36.2 and 36.3.)

THE OLDER ADULT AND EXERCISE

According to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia, up to half of the functional decline associated with ageing is the result of disuse and can be reversed by exercise. Exercise improves cardiopulmonary fitness, ability to stretch and balance and endurance. Benefits of regular exercise are particularly important for older adults, as being fit makes it easier to perform daily activities and improves recovery after illness as well as minimising the risk of future ill-health. Light exercise is beneficial and, as long as individuals ease into exercise, especially if they have led sedentary lives, there is nothing to stop older adults from starting a regular exercise program. However, it is wise that they consult with their medical officer first. (See Clinical Interest Box 36.4.)

OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

In Australia in 2001, 30% of adult males and 36% of adult females aged 45–74 considered themselves to be overweight. The prevalence of obesity (those with a body mass index [BMI] greater than 30) in Australians has risen from one in 14 in 1980, to one in seven in 1989, and one in five by 1995. Based on current trends, by 2025 it could be one in three. It is known that being severely overweight puts a load on the heart and increases the risk of high blood pressure and diabetes, but what was not known until fairly recently is just how many years of life are lost if a person is obese. In the late 1990s American researchers asked that simple question of tens of thousands of Americans and the results were compelling, with reports of females with BMIs over 30 (especially if about 20 years old) losing 5–8 years, and obese men up to 12 years. These data are easily transferable to Australia. (See Chapter 31 for further information on BMI.)

Childhood obesity is of particular concern because the evidence shows that one in three obese children will become obese adults, increasing their vulnerability to weight related diseases. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is generally caused by lack of physical activity, unhealthy eating patterns, or a combination of the two, with genetics and lifestyle both important determinants of a child’s weight. Nurses need to be aware that inactivity is a health risk and that obesity is a serious health risk, not just a cosmetic issue, and that obese people risk losing many productive years of their lives. Clinical Interest Box 36.5 provides an outline of some self-care behaviours and exercises.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 36.5 Self-care behaviours and exercise

TYPES OF EXERCISE

ISOTONIC, ISOMETRIC AND ISOKINETIC EXERCISE

Isotonic exercise involves muscle shortening and active contraction and relaxation of muscles and occurs with movement, such as carrying out activities of daily living, independent range-of-movement (ROM) exercises, swimming, walking, running, cycling or jogging. Examples of isotonic bed exercises are pushing or pulling against a stationary object, using a trapeze to lift the body off the bed, lifting the buttocks off the bed by pushing with the hands against the mattress and pushing the body to a sitting position (Kozier et al 2000).

Mechanical devices are available for specific joints, which place these joints through continuous passive ROM (CPM). These CPM machines are used postoperatively to place joints through a selective repetitive ROM. The CPM can be set to certain degrees of joint mobility, with increasing joint mobility or flexion as the required outcome (Crisp & Taylor 2005).

JOINT MOBILITY

RANGE-OF-MOVEMENT (ROM) EXERCISES

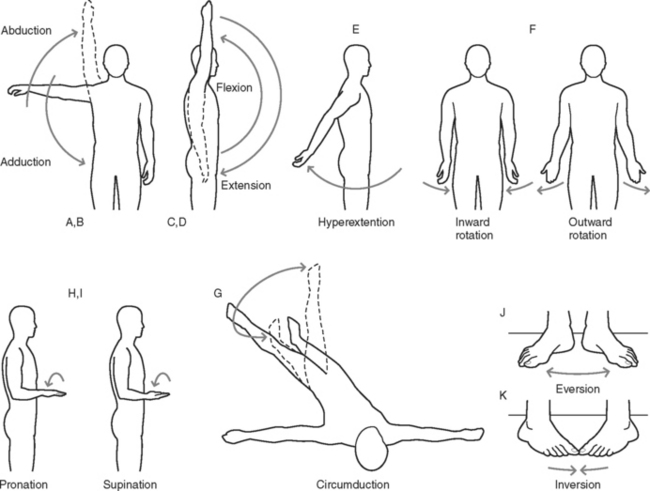

Joints are capable of a wide range of movement (Table 36.1). ROM or motion exercises are either active, when the clients are able to move the joints themselves, or passive, when the nurse moves clients’ joints within the normal ROM, noting joint flexibility and/or limitations of movement. ROM exercises are illustrated in Figure 36.5. Joints that are not moved regularly can develop contractures (shortening of a muscle and eventually ligaments and tendons and eventual loss of function). The following 11 terms are associated with joint movement:

| Type of movement | Joints where movement occurs |

|---|---|

| Flexion | Shoulder, hip, knee, elbow |

| Extension | Wrist, interphalangeal joints |

| Abduction | Shoulder, hip, joints between |

| Adduction | Metacarpals, wrist and phalanges, or metatarsals and phalanges |

| Rotation | Shoulder, radius and ulna joints, hip, the joint between the atlas and axis |

| Circumduction | Shoulder |

| Pronation or turning the palm downwards. | Radius and ulna joints |

| Supination or turning the palm upwards |

The frequency with which ROM exercises are performed depends on the client’s condition and medical and nursing management, but they are commonly performed at least twice daily. However, it is important not to overtire the client. ROM exercises may be performed independently or with assistance. Using appropriate movements, all joints are exercised in a logical sequence. Exercise routines are normally individually designed and the intensity and frequency depend upon the client’s general condition, level of fitness and capabilities.

DISEASES OF MUSCLES

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

This condition affects females more than males, usually occurs between age 20 and 40, and is an autoimmune disease of unknown origin. Defective muscle stimulation is caused by the development of antibodies that damage receptors in the neuromuscular junction, blocking impulses to muscle fibres. Progressive and extensive muscle weakness occurs, with the eyelids affected first by drooping (ptosis), and clients sometimes complaining of diplopia or double vision, owing to extraocular muscle weakness. The neck and limb muscles are affected next, with remissions and relapses precipitated by extreme exercise, infections, emotional disturbances and pregnancy.

DISORDERS OF JOINTS

The tissues involved in diseases of synovial joints are synovial membrane, cartilage and bone.

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the axial skeleton (spine and adjacent soft tissue) and has characteristics similar to those of rheumatoid arthritis, but the rheumatoid factor is absent. The cause is unknown but heredity, immune responses and infection are suspected. Signs and symptoms include gradual onset of back pain, decreased spinal mobility, peripheral arthritis and, in advanced stages, kyphosis (hunched back).

COMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Sprains, strains and fractures

Table 36.2 lists the various types of fractures, according to the way in which the bone has broken. Signs and symptoms vary but mostly there is pain, swelling, involuntary and painful muscle spasm, bruising, obvious deformity, abnormal mobility and loss of function. Crepitus (grating caused by bone fragments rubbing together) may be heard or felt. Shock may occur as a result of haemorrhage or extensive damage.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Greenstick | The fracture is incomplete and does not extend through the bone. The bone bends, and splits or cracks on one side |

| Transverse | The fracture line is straight across the bone |

| Oblique | The fracture line is at an angle across the bone |

| Spiral | The fracture line coils around the bone. This type of fracture generally results from twisting of the limb |

| Impacted | The fragments of broken bone are pushed (telescoped) into each other |

| Comminuted | The bone is broken into a number of fragments |

| Depressed | The broken edges are pushed below the level of the rest of the bone. This type of injury may occur when the skull is fractured |

| Avulsion | A fragment of bone, connected to a ligament, breaks off from the rest of the bone |

| Intracapsular | The fracture is within the joint capsule |

| Extracapsular | The fracture is close to a joint, but is outside the joint capsule |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree